ISO 16140 Method Verification: The Complete Guide for Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research Professionals

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive understanding of the ISO 16140 series for microbiological method validation and verification.

ISO 16140 Method Verification: The Complete Guide for Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research Professionals

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive understanding of the ISO 16140 series for microbiological method validation and verification. Covering foundational principles, practical implementation protocols, troubleshooting strategies, and validation frameworks, it addresses the critical need for standardized methods in pharmaceutical and clinical research. The content explores the distinct roles of method validation and verification, detailing the multi-stage processes outlined in ISO 16140 standards to ensure method reliability, regulatory compliance, and robust quality control in biomedical applications.

Understanding ISO 16140: Core Principles and Scope for Pharmaceutical Applications

The ISO 16140 series of international standards provides a critical framework for the validation and verification of microbiological methods used throughout the food and feed chains. These standards are designed to assist food and feed testing laboratories, test kit manufacturers, competent authorities, and food and feed business operators in implementing reliable microbiological methods that ensure the safety and quality of products [1]. The series establishes standardized protocols that help laboratories demonstrate their technical competence and generate reliable, reproducible results, which is particularly important in regulatory compliance and international trade.

Within the context of method verification standards, the ISO 16140 series creates a harmonized approach for confirming that analytical methods are fit for their intended purpose. The standards outline a two-stage process that must be completed before a method can be used routinely in a laboratory: first, proving that the method itself is fit for purpose (validation), and second, demonstrating that the laboratory can properly perform the method (verification) [1]. This structured approach provides confidence in microbiological test results that impact public health decisions.

The Structure of the ISO 16140 Series

The ISO 16140 series consists of seven distinct parts, each addressing specific aspects of method validation and verification. The development of this series represents a significant advancement in standardizing microbiological method evaluation, with each part serving a unique role in the overall ecosystem of method qualification. The following table provides a comprehensive overview of all seven parts and their specific scopes and applications.

Table: Overview of the ISO 16140 Parts and Their Specific Roles

| Standard Part | Title | Primary Focus and Application |

|---|---|---|

| ISO 16140-1 | Vocabulary | Defines terms and principles used throughout the series to ensure consistent interpretation [1]. |

| ISO 16140-2 | Protocol for the validation of alternative (proprietary) methods against a reference method | Core standard for validating commercial alternative methods; includes method comparison and interlaboratory study protocols [1]. |

| ISO 16140-3 | Protocol for the verification of reference methods and validated alternative methods in a single laboratory | Guides laboratories in demonstrating competence with validated methods before implementation [1]. |

| ISO 16140-4 | Protocol for method validation in a single laboratory | Validates methods within one laboratory without interlaboratory study; results apply only to that laboratory [1]. |

| ISO 16140-5 | Protocol for factorial interlaboratory validation for non-proprietary methods | Validates non-proprietary methods requiring rapid validation or when fewer laboratories are available [1]. |

| ISO 16140-6 | Protocol for the validation of alternative (proprietary) methods for microbiological confirmation and typing procedures | Validates confirmation procedures (e.g., biochemical confirmation) and typing techniques (e.g., serotyping) [1]. |

| ISO 16140-7 | Protocol for the validation of identification methods of microorganisms | Validates identification methods (e.g., PCR, DNA sequencing, mass spectrometry) where no reference method exists [1]. |

The relationships between the different parts of the standard are strategically designed to guide users in selecting the appropriate protocol based on their specific needs. According to the Introduction of parts 3, 4, and 5, a flow chart is provided that illustrates the links between the different parts of the ISO 16140 series and helps users select the right part based on the purpose of their study [1].

Core Concepts: Validation vs. Verification

A fundamental understanding of the ISO 16140 series requires a clear distinction between method validation and method verification, two related but distinct processes that are often confused.

Method Validation

Method validation is the primary process for proving that a method is fit for its intended purpose [1]. It answers the question: "Does this method work consistently and reliably to detect or quantify the target microorganism?" Validation is typically conducted through:

- A method comparison study where the alternative method is compared against a reference method, usually performed by one laboratory [1].

- An interlaboratory study that demonstrates the method's performance across multiple laboratories [1].

For alternative methods, ISO 16140-2 serves as the base standard, requiring both a method comparison study and an interlaboratory study [1]. The data generated during validation provides potential end-users with performance data for a given method, enabling informed decisions about implementation.

Method Verification

Method verification is the process where a laboratory demonstrates that it can satisfactorily perform a validated method [1]. It answers the question: "Can our laboratory successfully implement this validated method and obtain the expected results?" Verification applies only to methods that have been validated using an interlaboratory study and is described in ISO 16140-3 [1].

ISO 16140-3 outlines two distinct stages of verification:

- Implementation verification: The laboratory demonstrates it can perform the method correctly by testing one of the same items evaluated in the validation study [1].

- Item verification: The laboratory demonstrates capability in testing challenging food items within its scope of accreditation by testing several such items and confirming performance characteristics [1].

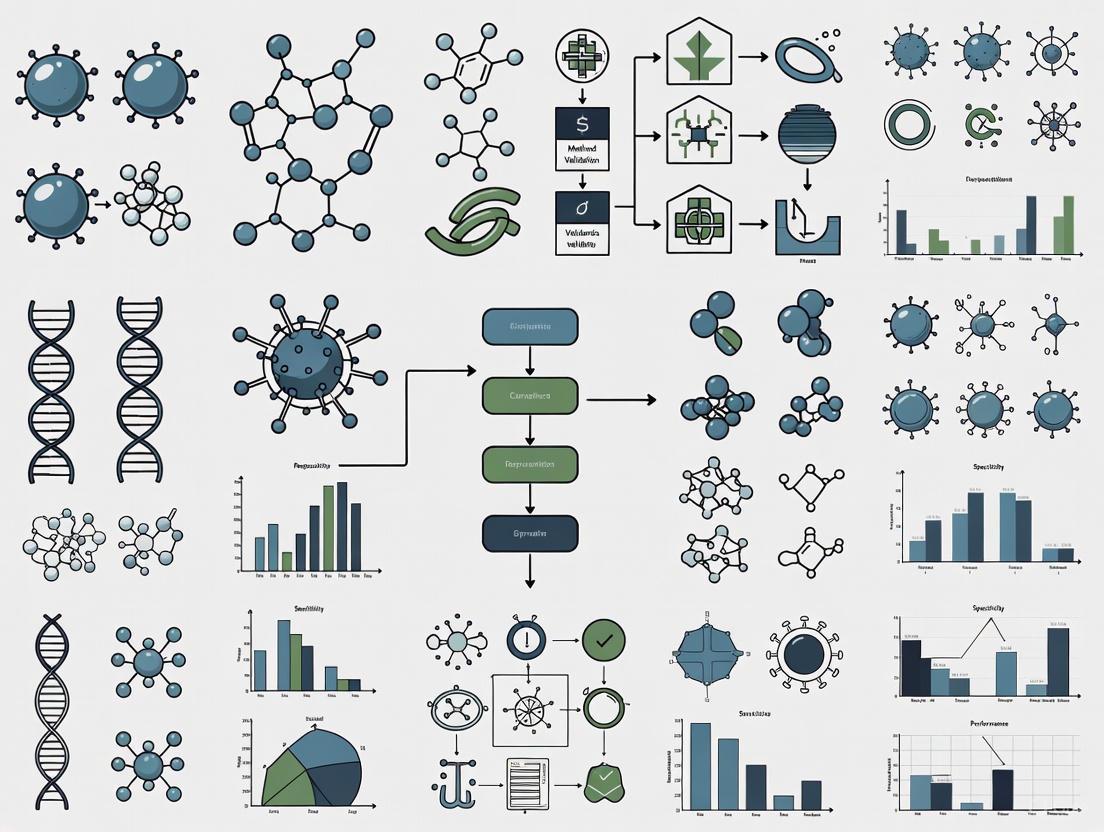

Diagram: Method Validation and Verification Workflow in ISO 16140

Detailed Examination of Each Part

ISO 16140-1: Vocabulary

As the foundational document of the series, ISO 16140-1 establishes the terminology and definitions used throughout the remaining parts. This standardization of language is critical for ensuring consistent interpretation and implementation across different stakeholders, including testing laboratories, kit manufacturers, and regulatory authorities. Without this common vocabulary, the technical requirements and performance criteria outlined in subsequent parts could be subject to varying interpretations, potentially compromising the reliability of method validation and verification studies.

ISO 16140-2: Validation of Alternative Methods

ISO 16140-2 represents the core validation standard for alternative (typically proprietary) microbiological methods against reference methods. This part includes comprehensive protocols for both qualitative and quantitative method validation, consisting of two mandatory phases: the method comparison study and the interlaboratory study [1]. The standard has recently been updated with Amendment 1 (published in September 2024), which introduced new calculations for qualitative method evaluation and the Relative Limit of Detection (RLOD) of the interlaboratory study [1]. A significant addition in this amendment addresses the validation of methods for commercial sterility testing for specific products like sterilized or UHT dairy and plant-based liquid products [1].

The data generated through ISO 16140-2 validation provides potential end-users with comprehensive performance data for a given method, enabling informed choices about implementation. These data also serve as the basis for certification of alternative methods by independent organizations, a process that also includes evaluation of the quality control during the method's manufacturing [1].

ISO 16140-3: Method Verification in a Single Laboratory

ISO 16140-3 provides the protocol for laboratories to verify that they can competently implement methods that have already been validated through an interlaboratory study (such as those validated according to ISO 16140-2) [1]. This standard is particularly important for laboratories accredited to ISO/IEC 17025, as they are required to perform verification of validated methods before implementation [2]. Even in non-accredited laboratories, verification following ISO 16140-3 is considered a best practice [2].

The verification process in ISO 16140-3 consists of two sequential stages:

- Implementation verification confirms that the user laboratory can perform the method correctly by testing one of the same items evaluated in the validation study [1].

- Item verification demonstrates that the laboratory can accurately test challenging items within its specific scope of application by testing several such items and confirming performance characteristics [1].

A 2025 amendment to ISO 16140-3 (AMD 1:2025) specifically addresses the protocol for verifying validated identification methods of microorganisms [3] [4].

ISO 16140-4: Single Laboratory Validation

ISO 16140-4 addresses situations where method validation occurs within a single laboratory without an interlaboratory study [1]. In such cases, the validation results are only applicable to the laboratory that conducted the study, and method verification as described in ISO 16140-3 is not applicable [1]. This approach may be suitable for specialized methods, methods developed in-house, or when limited resources prevent a full multi-laboratory study.

Amendment 2 of ISO 16140-4, published in 2025, specifies the protocol for single-laboratory validation of identification methods of microorganisms [1]. Additionally, Amendment 1 (published in 2024) addresses the validation of larger test portion sizes for qualitative methods [5], responding to industry needs for detecting low-level contaminants.

ISO 16140-5: Factorial Interlaboratory Validation for Non-Proprietary Methods

ISO 16140-5 describes protocols for the interlaboratory validation of non-proprietary methods in specific cases where a more rapid validation is required or when the method to be validated is highly specialized and the number of participating laboratories required by ISO 16140-2 cannot be reached [1]. Unlike ISO 16140-2, which is designed primarily for proprietary methods, this part addresses the validation of methods that are typically publicly available.

This standard can be used for validation against a reference method for both qualitative and quantitative methods, but can also be used for validation without a reference method for quantitative methods only [1].

ISO 16140-6: Validation of Confirmation and Typing Methods

ISO 16140-6 covers the validation of alternative confirmation methods and typing techniques, which represents a more specialized application compared to other parts of the series [1]. The standard is restricted to validation of confirmation procedures that advance a suspected result to a confirmed positive result, such as biochemical confirmation of Enterobacteriaceae [1]. It also covers validation of alternative typing techniques like serotyping of Salmonella [1].

A critical aspect of validation under ISO 16140-6 is that it clearly specifies the selective agar(s) from which strains can be confirmed using the alternative confirmation method. If successfully validated, the alternative confirmation method can only be used if strains are recovered on an agar that was used and shown to be acceptable within the validation study [1].

ISO 16140-7: Validation of Identification Methods

ISO 16140-7 addresses the validation of microbial identification procedures, such as molecular identification using multiplex PCR, DNA sequencing, or mass spectrometry [1]. This part differs significantly from other parts of the series because it is intended for microbial identification where no reference method exists, making traditional method comparison studies impossible [1].

Instead of comparing against a reference method, validation under ISO 16140-7 relies on testing a panel of well-characterized strains. The validation study must specify the identification method principle, the identification database and algorithm (when appropriate), and the agar(s) from which strains can be identified [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Validation Protocol for Alternative Methods (ISO 16140-2)

The validation process for alternative methods following ISO 16140-2 involves a rigorous two-phase approach designed to generate comprehensive performance data:

- Method Comparison Study: In this initial phase, the alternative method is compared against the reference method in a single laboratory. For qualitative methods, this involves testing inclusivity and exclusivity panels of target and non-target strains, as well as contaminated and uncontaminated food samples. For quantitative methods, this phase includes determination of quantitative performance characteristics such as accuracy profile, linearity, and measurement uncertainty.

- Interlaboratory Study: This phase involves a minimum of eight to ten laboratories testing a standardized set of contaminated and uncontaminated samples. The study includes five different food categories selected from fifteen defined categories, which enables the method to be regarded as validated for a "broad range of foods" [1]. The interlaboratory study evaluates interlaboratory consistency, relative accuracy, relative detection level, and relative specificity and sensitivity.

Verification Protocol in a Single Laboratory (ISO 16140-3)

The verification process for laboratories implementing previously validated methods involves a structured two-stage approach:

Implementation Verification Protocol:

- Select at least one food item that was used in the original validation study

- Test a minimum number of replicates (typically 5 uncontaminated and 5 contaminated test portions for qualitative methods)

- Compare results with expected outcomes from the validation study

- Demonstrate statistical equivalence for quantitative methods

Item Verification Protocol:

- Select challenging food items relevant to the laboratory's scope

- Include a minimum of five food items covering different categories

- Test contaminated and uncontaminated samples for each item

- Evaluate performance characteristics against defined criteria

- Document all procedures and results for assessment

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ISO 16140 Method Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation/Verification |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Strains | ATCC, NCTC, or other internationally recognized strains | Serve as target and non-target microorganisms for inclusivity/exclusivity testing [1]. |

| Selective Agar Media | Specific agars mentioned in validation studies (e.g., for Enterobacteriaceae confirmation) | Used for recovery of strains; validation is agar-specific [1]. |

| Artificially Contaminated Food Samples | Representative food categories (e.g., heat-processed milk, ready-to-eat foods) | Evaluate method performance in relevant matrices [1]. |

| Identification Reagents | PCR primers, sequencing kits, mass spectrometry matrices | Enable microbial identification in validation of identification methods [1]. |

Recent Developments and Amendments

The ISO 16140 series continues to evolve to address emerging needs in microbiological method validation. Several significant amendments have been published recently or are forthcoming:

- ISO 16140-2 Amendment 1 (2024): Introduced new calculations for qualitative method evaluation and RLOD of the interlaboratory study, with special attention to validation of methods for commercial sterility testing [1].

- ISO 16140-3 Amendment 1 (2025): Specified the protocol for verification of validated identification methods of microorganisms [3] [4].

- ISO 16140-4 Amendment 1 (2024): Addressed validation of larger test portion sizes for qualitative methods, with a transition period allowing existing laboratory-owned validation data until 2028 [1] [5].

- ISO 16140-4 Amendment 2 (2025): Provided protocol for single-laboratory validation of identification methods of microorganisms [1].

These amendments reflect the dynamic nature of microbiological testing and the need for standards to adapt to technological advancements and emerging challenges in food safety.

The ISO 16140 series provides a comprehensive, structured framework for the validation and verification of microbiological methods throughout the food chain. With its seven distinct parts, the series addresses the diverse needs of method developers, testing laboratories, and regulatory authorities by offering standardized protocols for different validation and verification scenarios. The clear distinction between method validation (proving a method is fit for purpose) and method verification (demonstrating laboratory competency with a validated method) represents a fundamental principle that ensures the reliability of microbiological testing.

The ongoing development of the series, evidenced by recent amendments addressing identification methods and larger test portion sizes, demonstrates the commitment to maintaining relevant and current standards. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the specific roles and applications of each part of the ISO 16140 series is essential for designing appropriate validation studies, properly implementing methods in laboratory settings, and ensuring the generation of reliable, defensible microbiological data that ultimately protects public health.

In regulated industries such as pharmaceuticals, food safety, and environmental monitoring, the reliability of analytical testing methods is paramount. Method validation and method verification represent two distinct but interconnected processes that ensure analytical methods are fit for their intended purpose and correctly implemented within a specific laboratory environment. Within the framework of the ISO 16140 series, which provides comprehensive guidance for microbiological methods in the food chain, these processes are formally defined and standardized [1]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the critical distinction between validation and verification is not merely academic—it is a fundamental requirement for regulatory compliance, data integrity, and ultimately, product safety and efficacy. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of both processes, their regulatory foundations, and detailed experimental protocols.

Defining the Concepts: Validation and Verification

Core Definitions and Regulatory Context

The distinction between method validation and verification is clearly established in international standards and regulatory guidelines.

Method Validation is a comprehensive, documented process that proves an analytical method is acceptable for its intended purpose [6] [7]. It is performed to demonstrate that the performance characteristics of a method meet the requirements for its specific analytical applications through rigorous laboratory studies [8]. Validation provides evidence that a method is scientifically sound and capable of producing reliable and reproducible results.

Method Verification is the process of confirming that a previously validated method performs as expected in a specific laboratory setting, with its particular personnel, equipment, and reagents [6] [9]. It is not a re-validation, but rather an assessment of how the analytical test procedure is suitable for its intended use under actual experimental conditions [8] [10].

The relationship between these processes is sequential: a method must first be validated to establish its performance characteristics, and then verified by each laboratory that implements it to confirm it functions correctly in that specific environment [1] [9].

When is Each Process Required?

The application of validation versus verification depends on the origin and status of the analytical method:

Method Validation is required when:

- Developing a new analytical method in-house [8].

- An established method is used for a new product or matrix outside its original validated scope [6].

- Submitting data for regulatory approvals, such as New Drug Applications (NDAs) or Biologic License Applications (BLAs) [6] [7].

- Transferring methods between labs or instruments where no prior validation data exists for the receiving lab [6].

Method Verification is required when:

- Implementing a compendial method (e.g., from USP, EP) for the first time in a laboratory [8] [10].

- Adopting a previously validated method from a client or another laboratory [8].

- Demonstrating competence for ISO/IEC 17025 accreditation [6] [2].

- Using standardized methods from organizations like EPA, AOAC, or ISO [6] [9].

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for determining whether validation or verification is needed:

Method Validation: Establishing Fitness for Purpose

Performance Characteristics and Assessment Protocols

Method validation requires a comprehensive assessment of multiple performance characteristics. The table below summarizes the key parameters, their definitions, and typical experimental protocols for assessment, based on ICH Q2(R1) and USP <1225> guidelines [8] [7].

Table 1: Key Performance Characteristics for Method Validation

| Performance Characteristic | Definition | Experimental Protocol & Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between the accepted reference value and the value found [8] [7]. | Protocol: Analyze a minimum of 3 concentration levels with 3 replicates each using spiked samples with known analyte concentrations. Assessment: Calculate percent recovery or difference from the true value. |

| Precision | The closeness of agreement between a series of measurements from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample [8] [7]. | Protocol: Includes repeatability (same conditions) and intermediate precision (different days, analysts, equipment). Assessment: Calculate relative standard deviation (RSD) or coefficient of variation (CV). |

| Specificity | The ability to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present [8] [7]. | Protocol: Analyze samples with and without potential interferents (impurities, matrix components). Assessment: Demonstrate that the response is due to the analyte alone. |

| Linearity | The ability of the method to obtain test results proportional to the concentration of the analyte [8]. | Protocol: Prepare and analyze a minimum of 5 concentration levels across the specified range. Assessment: Calculate correlation coefficient, y-intercept, and slope of the regression line. |

| Range | The interval between the upper and lower concentrations of analyte for which the method has suitable accuracy, precision, and linearity [8]. | Protocol: Established from linearity studies, typically confirmed at the range limits. Assessment: Verify that accuracy, precision, and linearity meet criteria across the range. |

| Detection Limit (LOD) | The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be detected, but not necessarily quantified [8] [7]. | Protocol: Based on visual evaluation, signal-to-noise ratio, or standard deviation of the response. Assessment: Lowest concentration that provides a detectable signal above background. |

| Quantitation Limit (LOQ) | The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision [8] [7]. | Protocol: Analyze multiple samples at low concentrations and determine where precision and accuracy become unacceptable. Assessment: Concentration that provides a signal with specified accuracy and precision (e.g., ≤20% RSD). |

| Robustness | The capacity of a method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters [8] [7]. | Protocol: Vary parameters such as pH, temperature, mobile phase composition, flow rate. Assessment: Evaluate the impact on method performance (precision, specificity). |

Regulatory Frameworks for Validation

Method validation is governed by several key regulatory guidelines:

- ICH Q2(R1): Provides the primary international guideline for validating analytical procedures, defining the key characteristics listed above [8] [7].

- USP General Chapter <1225>: Covers the validation of compendial procedures and categorizes methods based on the level of validation required [8] [10].

- FDA Guidance for Industry: Details validation requirements for Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) documentation in regulatory submissions [7].

For biological methods or those used in bioanalytical studies, the "FDA Bioanalytical Method Validation" guidance provides additional specific requirements [7].

Method Verification: Confirming Laboratory Competence

Scope and Requirements

Method verification confirms that a laboratory can satisfactorily perform a validated method [1]. According to USP <1226>, verification involves assessing "selected analytical performance characteristics to generate appropriate and relevant data, rather than repeating the entire validation process" [10]. The extent of verification depends on factors including the analyst's experience, the complexity of the method, and the specific article being tested [10].

The ISO 16140-3 standard specifically outlines two stages of verification for microbiological methods:

- Implementation Verification: Demonstrates that the user laboratory can perform the method correctly by testing one of the same items evaluated in the validation study [1].

- Item Verification: Demonstrates that the laboratory is capable of testing challenging items within its scope of accreditation by testing several such items and confirming performance characteristics [1].

Verification Protocols and Experimental Design

Unlike validation, verification does not require assessment of all performance characteristics. The parameters selected for verification should be those most critical to confirming the method works as intended in the new setting.

Table 2: Typical Verification Parameters and Experimental Approaches

| Verification Parameter | Typical Experimental Protocol | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy/Precision | Protocol: Analyze a minimum of 3 replicates at a single concentration level (for quantitative methods) or test reference materials with known status (for qualitative methods). ISO 16140-3 Approach: Follow the standard's specific protocol for implementation and item verification [1] [2]. | Criteria: Results fall within the validated method's specified range or established quality control limits. |

| Specificity/Selectivity | Protocol: Test the method against potentially interfering substances specific to the laboratory's sample matrices. | Criteria: No significant interference observed; method correctly identifies/quantifies analyte. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Protocol: For qualitative methods, confirm the validated LOD by testing low-level inoculated samples. | Criteria: Consistent detection at or below the validated LOD. |

| Linearity/Range | Protocol: For quantitative methods, a limited linearity check with 3-4 data points may be sufficient. | Criteria: Correlation coefficient meets the method's specified requirement. |

| Robustness | Protocol: Minor, intentional variations in critical parameters (if applicable to the laboratory's specific implementation). | Criteria: Method performance remains acceptable despite variations. |

For laboratories implementing a compendial HPLC method, verification might focus primarily on precision and specificity, whereas for a microbiological method like an enzyme substrate test for water quality, verification would focus on specificity, selectivity, and repeatability through side-by-side comparison of 10-20 split samples [9] [10].

Comparative Analysis: Validation vs. Verification

The table below provides a direct comparison of the key attributes of method validation and verification, highlighting their distinct roles and requirements.

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Method Validation and Verification

| Aspect | Method Validation | Method Verification |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Prove the method is fit for its intended purpose [8] [6]. | Confirm the laboratory can properly perform the validated method [1] [6]. |

| When Performed | During method development; for new methods; for regulatory submissions [8] [6]. | When implementing a previously validated method in a new laboratory for the first time [8] [9]. |

| Scope | Comprehensive assessment of all relevant performance characteristics [8] [7]. | Limited assessment of selected performance characteristics deemed appropriate for the specific context [6] [10]. |

| Regulatory Basis | ICH Q2(R1), USP <1225>, FDA guidance [8] [7]. | USP <1226>, ISO 16140-3, ISO/IEC 17025 [1] [10]. |

| Resource Intensity | High (time-consuming, resource-intensive, costly) [6]. | Moderate (faster, more economical) [6]. |

| Data Requirements | Extensive data set to fully characterize the method [8] [7]. | Sufficient data to demonstrate laboratory competence with the method [6] [10]. |

| Primary Responsibility | Method developer or originating laboratory [8]. | User laboratory implementing the method [9]. |

The ISO 16140 Framework for Microbiological Methods

The ISO 16140 series, "Microbiology of the food chain - Method validation," provides a standardized international approach for the validation and verification of microbiological methods, particularly for food and feed testing [1]. The series consists of multiple parts, each addressing specific aspects of the validation and verification process:

- ISO 16140-1: Vocabulary [1]

- ISO 16140-2: Protocol for the validation of alternative (proprietary) methods against a reference method [1]

- ISO 16140-3: Protocol for the verification of reference methods and validated alternative methods in a single laboratory [1] [2]

- ISO 16140-4: Protocol for method validation in a single laboratory [1]

- ISO 16140-5: Protocol for factorial interlaboratory validation for non-proprietary methods [1]

- ISO 16140-6: Protocol for the validation of alternative methods for microbiological confirmation and typing procedures [1]

- ISO 16140-7: Protocol for the validation of identification methods of microorganisms [1]

Implementation of ISO 16140-3 for Verification

The publication of ISO 16140-3 in 2021 provided the first internationally recognized standard for the verification of microbiological methods [2]. This standard is particularly relevant for laboratories accredited to ISO/IEC 17025, which requires verification of validated methods before implementation [2]. The standard guides laboratories through the process of selecting appropriate food categories and items for verification, ensuring that the method performs as expected for the specific sample types tested within the laboratory's scope [1].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials commonly required for method validation and verification studies, particularly in microbiological and chemical analyses.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Method Validation/Verification

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application in Validation/Verification |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provide a known, traceable quantity of analyte for establishing accuracy, precision, and linearity during validation [7]. |

| Quality Control Strains | For microbiological methods, used to verify specificity, LOD, and accuracy during verification studies [9]. |

| Inoculated/Spiked Samples | Samples with a known concentration of analyte (microorganism or chemical) used to assess recovery, accuracy, and LOD [9]. |

| Selective Culture Media | Used in microbiological methods to assess specificity by differentiating target microorganisms from non-target organisms [1]. |

| Internal Standards | For chromatographic methods, used to normalize results and improve the precision and accuracy of quantification [8]. |

| Matrix-Blank Samples | Samples free of the target analyte used to demonstrate the absence of interference, confirming method specificity [7]. |

Method validation and method verification are distinct but complementary processes that form the foundation of reliable analytical testing in regulated environments. Validation is a comprehensive process to establish that a method is scientifically sound and fit for its intended purpose, while verification is a targeted process to confirm that a laboratory can successfully implement a previously validated method. The ISO 16140 series provides a critical framework for these processes in microbiological testing, with ISO 16140-3 offering specific guidance for method verification. For researchers and drug development professionals, a clear understanding of these processes, their respective requirements, and the associated experimental protocols is essential for generating reliable data, maintaining regulatory compliance, and ensuring product quality and safety.

In regulated scientific fields, demonstrating the reliability of analytical methods and the competence of the personnel performing them is a foundational requirement. The two-stage framework of method validation (proving a method is fit-for-purpose) and method verification (proving a laboratory can competently perform the method) provides a systematic approach to ensuring data integrity. This framework is codified in international standards, most notably the ISO 16140 series for microbiology, and is supported by broader laboratory competence standards like ISO/IEC 17025. This guide provides an in-depth technical exploration of this framework, detailing the experimental protocols, competency requirements, and documentation needed for compliance and scientific rigor. Adherence to this structured process is critical for generating reliable, defensible data in research and drug development.

Before any laboratory implements a new test method for routine use, it must answer two critical questions: First, is the method itself technically sound and fit for its intended purpose? Second, can our laboratory personnel and systems execute this method correctly and consistently? The two-stage framework directly addresses these questions through distinct, sequential processes.

- Stage 1: Method Validation is the process of proving through an objective experiment that a method is fit-for-purpose. It answers the question, "Does this method work?" According to the ISO 16140 series, validation is conducted to provide evidence that a method meets the performance criteria for its intended application [1]. This stage is typically performed by the method developer or manufacturer and involves rigorous testing against a reference method in a multi-laboratory study to establish its performance characteristics, such as accuracy, precision, and specificity [1].

- Stage 2: Method Verification is the process by which a laboratory provides objective evidence that it has the competence and capability to successfully perform a validated method. It answers the question, "Can we perform this method correctly in our lab?" As outlined in ISO 16140-3, verification is where "a laboratory demonstrates that it can satisfactorily perform a validated method" [1]. For laboratories accredited to ISO/IEC 17025, this is not merely a best practice but a mandatory requirement [2].

The logical relationship between these stages is sequential and interdependent, as illustrated below.

The Sequential Workflow of Method Validation and Verification

Stage 1: Proving Method Fitness (Validation)

Method validation is the foundational first stage, providing the performance data that proves a method's reliability.

Key Validation Standards and Protocols

The ISO 16140 series provides a comprehensive structure for the validation of microbiological methods. The selection of the appropriate validation protocol depends on the method type and the goal of the study [1].

Table: Parts of the ISO 16140 Series for Method Validation

| ISO Standard Part | Title | Scope and Application |

|---|---|---|

| ISO 16140-2 | Protocol for the validation of alternative (proprietary) methods against a reference method | The base standard for alternative method validation; includes a method comparison study and an interlaboratory study [1]. |

| ISO 16140-4 | Protocol for method validation in a single laboratory | Used when validation is conducted within one laboratory only; results are specific to that lab [1]. |

| ISO 16140-5 | Protocol for factorial interlaboratory validation for non-proprietary methods | For validation of non-proprietary methods in specific cases requiring rapid validation or when a full number of labs cannot be recruited [1]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Validation

For a validation study against a reference method according to ISO 16140-2, the protocol is highly structured. The following methodology outlines the core steps for a quantitative method.

Study Design and Planning:

- Objective: To demonstrate the alternative method's performance is equivalent or non-inferior to the reference method.

- Sample Types: Select a minimum of five different food categories (e.g., heat-processed milk, raw poultry, ready-to-eat foods) out of a defined list of 15 to represent a "broad range of foods" [1].

- Inoculation: Artificially inoculate food samples with target microorganisms at multiple predetermined contamination levels, including low, medium, and high counts for quantitative methods.

Method Comparison Study (Primary Validation):

- Testing: Analyze the inoculated samples in parallel using both the alternative method and the reference method.

- Replication: Perform a sufficient number of replicates (e.g., n=5 per contamination level) to ensure statistical power.

Interlaboratory Study:

- Collaboration: Engage a minimum number of independent laboratories to repeat the method comparison study.

- Purpose: This confirms the method's robustness and transferability across different laboratory environments, operators, and equipment.

Data Analysis and Performance Characterization: Calculate the following key performance indicators from the collected data:

- Accuracy/Relative Accuracy: The closeness of agreement between the results from the alternative method and the reference method.

- Precision: Expressed as repeatability (within-lab) and reproducibility (between-lab) standard deviations.

- Linearity: The ability of the method to obtain results directly proportional to the analyte concentration.

- Limit of Detection (LOD): The lowest quantity of the analyte that can be detected.

- Limit of Quantification (LOQ): The lowest quantity of the analyte that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy.

Stage 2: Demonstrating Laboratory Competence (Verification)

Once a method is validated, the responsibility shifts to the individual laboratory to prove its competence in performing it.

The Verification Mandate

Verification is a critical requirement for laboratories operating under ISO/IEC 17025 accreditation [2]. Even for non-accredited labs, it is considered a fundamental best practice [2]. The international standard ISO 16140-3:2021 provides specific guidance on how to verify microbiological methods, offering a unified protocol that was lacking prior to its publication [2].

The Two-Stage Verification Protocol (ISO 16140-3)

ISO 16140-3 breaks down verification into two distinct stages, each with a specific purpose [1].

Table: The Two Stages of Method Verification per ISO 16140-3

| Verification Stage | Purpose | Key Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation Verification | To demonstrate the user laboratory can perform the method correctly as per the validated protocol. | Testing one of the same food items used in the original validation study and comparing results to show the laboratory can achieve similar performance [1]. |

| Food Item Verification | To demonstrate the method performs satisfactorily for the specific, and potentially challenging, sample types routinely tested by the laboratory. | Testing several food items that are specific to the laboratory's scope and confirming method performance using defined characteristics [1]. |

The following diagram maps the decision-making workflow a laboratory must follow to successfully verify a method.

Laboratory Workflow for Method Verification

Personnel Competency Requirements (ISO/IEC 17025)

Underpinning the entire verification process is the requirement for demonstrably competent personnel, as mandated in section 6.2 of ISO/IEC 17025 [11]. The standard requires laboratories to:

- Document competence requirements for each role influencing laboratory results, including education, training, skills, and experience [11].

- Implement procedures for determining competence, selecting, training, supervising, and authorizing personnel [11].

- Continuously monitor competence through techniques like observation, proficiency testing, and peer review [11].

This aligns with global best practices for laboratory workforce competency, which emphasize the need to assess personnel through direct observation, review of quality control records, and evaluation of problem-solving skills [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The execution of validated and verified methods relies on a suite of essential materials. The following table details key reagent solutions used in microbiological method validation and verification studies.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Method Validation & Verification

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Reference Strains | Well-characterized microbial strains from culture collections (e.g., ATCC) used for inoculating samples to assess method accuracy, specificity, and limit of detection. |

| Selective and Non-Selective Media | Agar and broths used to cultivate, isolate, and differentiate target microorganisms from background flora; critical for comparing growth between reference and alternative methods. |

| Buffered Diluents | Solutions like Buffered Peptone Water used to homogenize samples and maintain osmotic balance and pH, ensuring microbial viability during testing. |

| Inactivation Solutions | Chemicals or reagents used to neutralize disinfectants or antimicrobials in a sample (e.g., in commercial sterility testing) to prevent false-negative results. |

| Quality Control Cultures | Strains used to verify the performance and sterility of media, reagents, and the overall testing process on each day of testing. |

| Proprietary Enrichment Media & Substrates | Specialized broths and chromogenic/fluorogenic compounds specific to alternative rapid methods that facilitate the detection and identification of target microbes. |

| (2E,11Z)-octadecadienoyl-CoA | (2E,11Z)-octadecadienoyl-CoA, MF:C39H66N7O17P3S, MW:1030.0 g/mol |

| 3,6-Dihydroxytetradecanoyl-CoA | 3,6-Dihydroxytetradecanoyl-CoA, MF:C35H62N7O19P3S, MW:1009.9 g/mol |

The two-stage framework of validation and verification is a non-negotiable pillar of quality assurance in scientific research and drug development. This structured approach transforms subjective trust into objective evidence. Method validation, governed by standards like ISO 16140-2 and -4, generates the foundational data proving a method is scientifically sound. Method verification, as detailed in ISO 16140-3 and supported by the personnel competency requirements of ISO/IEC 17025, provides the critical proof that a laboratory has the technical capability to implement the method successfully. By rigorously applying this framework, laboratories and researchers can ensure the generation of reliable, defensible, and high-quality data that drives innovation and ensures safety.

The ISO 16140 series of standards, initially developed for the food and feed sectors, provides a robust framework for the validation and verification of microbiological methods. While these standards are foundational in food safety testing, their principles and structured protocols hold significant, yet often underutilized, potential for pharmaceutical microbiology. This technical guide explores the application of ISO 16140, particularly Part 3 on method verification, within pharmaceutical drug development and quality control. Adherence to such internationally recognized validation protocols enhances the reliability of microbiological test results, which is paramount for ensuring the safety and quality of sterile and non-sterile pharmaceutical products, water systems, and manufacturing environments [13] [14].

The core principle of the ISO 16140 series is a two-stage process before a method is put into routine use: first, proving the method itself is fit-for-purpose (validation), and second, demonstrating that the user laboratory can properly perform the method (verification) [1]. This systematic approach is directly transferable to the highly regulated pharmaceutical industry, where method reliability is non-negotiable.

The ISO 16140 Framework: Core Concepts and Structure

Anatomy of the ISO 16140 Series

The ISO 16140 series is a multi-part standard, with each part addressing a specific aspect of method validation or verification. For a pharmaceutical laboratory seeking to implement a new microbiological method, understanding the role of each part is crucial. The following table summarizes the scope of the key parts within the series.

Table 1: Core Parts of the ISO 16140 Series Relevant to Method Implementation

| Standard Part | Title | Primary Focus | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISO 16140-1 | Vocabulary [1] | Defines terminology used across the series [15]. | Foundational for ensuring consistent understanding of terms like validation, verification, inclusivity, and exclusivity. |

| ISO 16140-2 | Protocol for the validation of alternative methods against a reference method [1] | Base standard for validating proprietary (commercial) methods via a method comparison study and an interlaboratory study [1] [15]. | Conducted by test kit manufacturers to generate performance data for end-users. |

| ISO 16140-3 | Protocol for the verification of reference and validated alternative methods in a single laboratory [1] [14] | Provides the protocol for a user laboratory to demonstrate its competence in performing a validated method before routine use [13] [1]. | Critical for pharmaceutical quality control labs implementing a new method. |

| ISO 16140-4 | Protocol for method validation in a single laboratory [1] | Allows for validation within a single lab without an interlaboratory study. Results are only valid for that lab [1]. | Applicable for non-proprietary methods or when a full validation is not feasible. |

| ISO 16140-7 | Protocol for the validation of identification methods of microorganisms [1] | Addresses validation of identification procedures (e.g., PCR, MS) where no reference method exists [1]. | Highly relevant for pharmaceutical labs using modern techniques for microbial identification. |

Validation vs. Verification: A Critical Distinction

A fundamental concept within the ISO 16140 framework is the clear distinction between method validation and method verification. These are sequential but distinct activities:

- Method Validation: This is the primary process of proving that a new or alternative method is fit for its intended purpose. Validation provides objective evidence that a method meets the performance requirements for its application [1]. This is typically the responsibility of the method developer or manufacturer and is performed according to parts like ISO 16140-2 or -4.

- Method Verification: This is the subsequent process where a user laboratory demonstrates that it can satisfactorily perform a method that has already been validated [1]. As defined in ISO 16140-3, a user laboratory is a "laboratory that implements a validated alternative method and/or a validated reference method" [16]. Verification confirms that the laboratory's execution of the method aligns with the performance characteristics established during the initial validation.

For a pharmaceutical quality control laboratory, verification (ISO 16140-3) is the standard most directly applicable to introducing a new commercial test kit or a pharmacopeial method into its quality system.

ISO 16140-3: The Verification Protocol for User Laboratories

The Two-Stage Verification Process

ISO 16140-3 outlines a structured two-stage protocol for verification, which ensures a laboratory is not only technically competent but also that the method is suitable for its specific testing needs [1].

Table 2: The Two Stages of Method Verification per ISO 16140-3

| Verification Stage | Purpose | Key Activities | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation Verification | To demonstrate that the user laboratory can perform the method correctly [1]. | Testing one of the same items (e.g., a specific matrix or sample type) that was used during the method's original validation study [1]. | The laboratory's results must be comparable to those achieved during the method's validation. |

| Item Verification | To demonstrate that the method performs satisfactorily for the specific, and potentially challenging, items within the laboratory's own scope of testing [1]. | Testing several "food items" or, in a pharmaceutical context, specific sample types (e.g., active pharmaceutical ingredients, finished products, water) that the lab routinely tests [1]. | Performance must meet pre-defined characteristics (e.g., sensitivity, specificity) for those specific items. |

This workflow illustrates the logical sequence and decision points in the ISO 16140-3 verification process:

A Practical Case: Verification of aListeriaPCR Method

A 2024 study provides a clear template for applying ISO 16140-3 to a rapid microbiological method, in this case, a qualitative real-time PCR (qPCR) assay for detecting Listeria spp. and Listeria monocytogenes [17]. While the study focused on food and environmental swabs, its methodology is directly adaptable to pharmaceutical processing environments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Method Verification [17]

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Verification Study | Specific Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Strain | Serves as a known positive control to inoculate samples for accuracy and detection limit studies. | Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 19115 (3-5 CFU per sample) [17]. |

| Culture Media | Used for sample enrichment and growth promotion testing. | Half-Fraser Broth [17]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolates microbial DNA from the sample matrix for subsequent PCR analysis. | SureFast PREP Bacteria kit (r-biopharm) [17]. |

| qPCR Master Mix & Kit | Provides the enzymes, buffers, and probes necessary for the amplification and detection of target DNA. | SureFast Listeria 3plex ONE kit (r-biopharm) [17]. |

| Sample Matrices | Represents the actual items tested during verification. | Implementation: Commercial milk powder. Item: Environmental swabs in Half-Fraser broth [17]. |

Experimental Protocol for Verification [17]:

Sample Preparation and Inoculation:

- For implementation verification, seven 25 g samples of a representative matrix (e.g., milk powder) were diluted with 225 mL of enrichment broth and inoculated with a low count (3-5 CFU) of L. monocytogenes. One uninoculated sample served as a blank.

- For item verification, seven environmental swabs diluted in 10 mL of enrichment broth were similarly inoculated. This mimics the critical environmental monitoring of a pharmaceutical cleanroom.

Incubation and Plating: All inoculated samples and blanks were incubated for 18-20 hours at 37°C. A plate count on Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) was performed concurrently to confirm the inoculation level.

DNA Extraction: DNA was extracted from the enriched samples using a commercial kit. The study compared a full extraction protocol with a rapid lysis buffer method, highlighting the importance of verifying the entire analytical process.

Real-Time PCR Amplification:

- The qPCR master mix was prepared according to the kit's instructions.

- All samples were analyzed in triplicate to ensure result consistency.

- The run included essential controls: No-Template Control (NTC), Extraction Control, Positive Control (PC), and a Medium Control.

Analysis and Acceptance: The method was considered verified as it successfully detected the target organism in all inoculated samples and gave negative results for all blanks, meeting the pre-defined performance criteria for qualitative methods.

Translating ISO 16140 to Pharmaceutical Microbiology

Strategic Applications and Adaptation

The principles of ISO 16140-3 are highly adaptable to the unique demands of pharmaceutical quality control and R&D. Key application areas include:

- Rapid Microbial Methods (RMMs): The pharmaceutical industry is increasingly adopting RMMs like PCR, flow cytometry, and ATP bioluminescence. These technologies are ideal candidates for a rigorous verification process following ISO 16140-3, which provides a structured protocol to demonstrate their equivalence or superiority to traditional, compendial methods [17].

- Environmental Monitoring: The case study using environmental swabs [17] is directly applicable to the verification of methods used to monitor pharmaceutical cleanrooms for objectionable microorganisms. Item verification would be crucial for different types of surface materials (stainless steel, epoxy resin) and locations within a facility.

- Utility Testing: Methods for testing Water-for-Injection (WFI) and Purified Water systems for microbial counts and specific pathogens can be verified using this framework, ensuring the method is suitable for this low-bioburden matrix.

- Raw Material and Finished Product Testing: The verification process ensures that methods used to test complex matrices, such as active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) or finished drug products (e.g., creams, suspensions), are not adversely affected by the product's formulation.

Navigating the "Scope" in a Pharmaceutical Context

A central concept in ISO 16140-3 is the management of "scope" – the range of samples for which a method is applicable [1]. The standard defines:

- Scope of Validation: The sample types for which the method developer has validated the method.

- Scope of the Laboratory Application: The sample types a user laboratory intends to test.

For a pharmaceutical lab, the "categories" are not food types, but rather product types (e.g., sterile solids, sterile liquids, non-sterile creams, water). The item verification stage is where the laboratory must provide evidence that the method is fit for its specific, often narrow, range of tested materials, even if the method was initially validated for a "broad range" of samples [1].

The ISO 16140 series, and ISO 16140-3 in particular, offers a powerful, systematic, and internationally recognized framework for the verification of microbiological methods in pharmaceutical microbiology. By adopting its structured two-stage protocol of implementation and item verification, pharmaceutical researchers and quality control professionals can generate robust, defensible data to support the introduction of new methods. This not only strengthens the overall quality system but also facilitates the adoption of innovative, rapid technologies, ultimately enhancing product safety and accelerating drug development. As the industry evolves, the principles encapsulated in these standards provide a solid foundation for ensuring the reliability and accuracy of microbiological data upon which patient safety depends.

This technical guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding the essential vocabulary established in ISO 16140-1:2016, which serves as the foundational lexicon for all method validation and verification activities within the food chain microbiology sector. As a critical component of a broader research thesis on ISO 16140 method verification standards, this document systematically organizes key terms, defines their technical significance, and illustrates their practical applications within experimental protocols. The structured vocabulary enables professionals to navigate complex validation workflows with precision, ensuring consistent interpretation and implementation of methods across laboratories and research institutions. By establishing a common technical language, ISO 16140-1 facilitates clearer communication between test kit manufacturers, accreditation bodies, and end-users, ultimately contributing to greater food and pharmaceutical safety through more reliable microbiological testing outcomes.

The ISO 16140 series of standards was developed to address the critical need for validated food microbiology methods in response to the proliferation of alternative (often proprietary) testing methods appearing on the market [15]. Before this standardization, laboratories lacked a unified protocol for validating these new methods against traditional reference cultures, creating potential inconsistencies in reliability and interpretation of results. The multipart standard provides specific protocols and guidelines for the validation of methods, both proprietary (commercial) and non-proprietary [18].

Within this framework, ISO 16140-1:2016, "Microbiology of the food chain - Method validation - Part 1: Vocabulary," serves as the terminological foundation upon which all other parts are built [15] [18]. This standard establishes a common technical language that ensures consistent understanding and application across the entire method validation and verification process. Its importance is underscored by its application across diverse stakeholders, including food and feed testing laboratories, test kit manufacturers, competent authorities, and food and feed business operators [18]. The vocabulary defined in Part 1 enables precise communication regarding method performance characteristics, validation requirements, and verification protocols, thereby supporting the overall objective of the ISO 16140 series: to enhance the reliability of microbiological test results and contribute to greater product safety [15].

Table: Structure of the ISO 16140 Series

| Standard Part | Title | Focus Area | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISO 16140-1:2016 | Vocabulary | Terminology used in microbial testing | Published |

| ISO 16140-2:2016 | Protocol for the validation of alternative methods against a reference method | Validation of proprietary methods | Published |

| ISO 16140-3 | Protocol for verification of reference and validated alternative methods in a single laboratory | Single-laboratory verification | Recently amended (2025) |

| ISO 16140-4 | Protocol for single-laboratory (in-house) method validation | In-house validation | Under development |

| ISO 16140-5 | Protocol for factorial interlaboratory validation for non-proprietary methods | Interlaboratory validation | Under development |

| ISO 16140-6:2019 | Protocol for validation of alternative methods for microbiological confirmation and typing | Confirmation and typing procedures | Published |

Core Vocabulary from ISO 16140-1:2016

Fundamental Validation Terminology

Understanding the precise definitions of fundamental validation terms is critical for proper implementation of microbiological methods. These terms establish the performance benchmarks and acceptance criteria that determine whether a method is suitable for its intended purpose.

Validation: The process of demonstrating that an alternative method is at least as effective as the reference method for detecting or enumerating the target microorganism [15]. The process includes two main phases: the method comparison study and the interlaboratory study, with separate protocols for qualitative and quantitative methods [18]. Validation according to ISO 16140-2 leads to higher reliability of alternative method test results [15].

Verification: The process conducted by an end-user to demonstrate their competence in properly implementing a previously validated method within their own laboratory [19]. The ISO 16140-3 standard specifically addresses the verification protocol for reference and validated alternative methods implemented in a single laboratory, filling a previous gap in internationally accepted guidelines for this purpose [19].

Reference Method: A standardized method used as the benchmark against which alternative methods are compared during validation [15]. The technical requirements and guidance for establishing or revising standardized reference methods are provided in ISO 17468:2016 [19].

Alternative Method: A method, often proprietary, that may differ in principle or technique from the reference method but is designed to achieve the same analytical outcome [15] [18]. These methods are generally cheaper to use, produce results faster than traditional culturing methods, and require fewer technical skills to perform [18].

Proprietary Method: A commercially developed and distributed alternative method, typically characterized by standardized reagents, equipment, and protocols supplied by a manufacturer [15] [18]. Over a hundred alternative methods have been validated based on the ISO 16140 standard [15].

Method Performance Characteristics

The following performance characteristics form the basis for evaluating and comparing microbiological methods in validation studies. These parameters provide the quantitative metrics necessary to objectively assess method reliability.

Table: Key Method Performance Characteristics in ISO 16140-1

| Term | Definition | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between a test result and an accepted reference value | Quantitative enumeration methods |

| Precision | The closeness of agreement between independent test results obtained under stipulated conditions | Both qualitative and quantitative methods |

| Specificity | The ability of a method to detect the target microorganism without interference from related non-target microorganisms | Detection and confirmation methods |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest level of microorganisms that can be detected in a specified matrix | Qualitative detection methods |

| Relative Detection Level | The probability of detection of an alternative method relative to the reference method | Comparative method validation studies |

Scope-Related Definitions

The concept of "scope" is critically important in both validation and verification activities, as it defines the boundaries of applicability for any given method. ISO 16140-1 establishes precise definitions for different types of scope that must be distinguished.

Scope of the Method: The full range of matrices (food categories, ingredients, environmental samples) and microorganisms for which the method is designed to be applicable [19]. This represents the manufacturer's intended use claims for the method.

Scope of the Method Validation: The specific matrices and microorganisms for which the applicability of the method has been experimentally demonstrated through a formal validation study according to ISO 16140-2 [19]. This scope is typically narrower than the full scope of the method.

Scope of Laboratory Application: The specific matrices and microorganisms for which an end-user laboratory applies a validated method within their routine testing activities [19]. The laboratory must verify competence for each category included in this scope.

The relationship between these different scopes forms the basis for the verification process outlined in ISO 16140-3, where laboratories must demonstrate their ability to properly perform methods within their specific application scope before introducing them for routine use [19].

Experimental Protocols and Verification Workflows

Method Verification Process in a Single Laboratory

The method verification process according to ISO 16140-3 follows a structured two-step approach based on the scope definitions, designed to ensure laboratory competence and result reliability [19]. This protocol provides the methodological framework that laboratories must implement when introducing previously validated methods.

The first step, implementation verification, aims to demonstrate the fundamental competence of the laboratory personnel to perform the method correctly according to the established protocol [19]. This is achieved by testing a single matrix or food item and obtaining results that meet predefined acceptability criteria, confirming that the laboratory can technically execute the method procedures.

The second step, item verification, addresses the laboratory's ability to apply the method to the specific matrices or food items that fall within their routine testing scope [19]. For this step, laboratories must strategically select challenging items that represent the scope of their application, potentially including multiple categories with different chemical and physical properties that might affect method performance.

Protocol for Verification of Identification Methods

The recently published Amendment 1 (2025) to ISO 16140-3:2021 introduces a specific "Protocol for verification of validated identification methods of microorganisms" [20] [21]. This amendment extends the verification framework to include microbial identification techniques, which are crucial for confirmation and typing procedures in both food and pharmaceutical microbiology.

While the specific experimental details of the new amendment are not fully elaborated in the available search results, the protocol likely follows the same fundamental principles as the broader verification framework while addressing the unique aspects of identification methods. These would include:

- Reference Strain Verification: Using well-characterized microbial strains to confirm the method's identification capabilities.

- Challenge Panels: Testing against closely related non-target organisms to confirm specificity.

- Blinded Samples: Incorporating proficiency testing elements to objectively assess performance.

- Comparison to Reference Methods: Parallel testing with established identification protocols.

This amendment reflects the ongoing evolution of the ISO 16140 series to address emerging methodological needs and technological advancements in microbiological testing [20].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of methods following ISO 16140 vocabulary requires specific research reagents and materials that ensure consistency, reliability, and reproducibility across laboratories. The following table details key components of the research reagent solutions essential for method validation and verification studies.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ISO 16140 Compliance

| Reagent/Material | Technical Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Strains | Well-characterized microorganisms serving as positive controls and for specificity testing | Method validation, implementation verification, ongoing quality control |

| Certified Reference Materials | Matrix materials with certified microbial counts or presence/absence for target organisms | Accuracy studies, method comparison, verification procedures |

| Selective Enrichment Media | Culture media promoting growth of target microorganisms while inhibiting competitors | Reference method procedures, cultural confirmation steps |

| Chromogenic Substrates | Biochemical compounds producing color changes upon enzyme activity of specific microorganisms | Alternative method components, confirmation tests, identification protocols |

| Inactivation Reagents | Chemical solutions that neutralize antimicrobial components in samples | Product validity testing, recovery improvement in challenging matrices |

| Performance Testing Cultures | Standardized microbial suspensions for demonstrating method competence | Implementation verification, laboratory proficiency testing |

These reagents form the foundation of both validation and verification studies, enabling laboratories to generate reliable performance data and make informed decisions about method adoption and implementation [15] [19]. The use of standardized, well-characterized reagents is essential for demonstrating that a laboratory can achieve the required performance standards before implementing methods for routine testing [19].

The specialized vocabulary established in ISO 16140-1:2016 provides an indispensable technical foundation for all stakeholders involved in microbiological method validation and verification within the food chain and related sectors. This standardized terminology creates the essential common language that enables clear communication between method developers, validation bodies, accreditation authorities, and end-user laboratories. As the ISO 16140 series continues to evolve with new parts and amendments—including the recently published Amendment 1 to Part 3 addressing identification methods—the vocabulary in Part 1 will continue to serve as the cornerstone for interpretation and implementation [20] [15].

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastery of this terminology is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for designing robust validation studies, properly implementing methods in laboratory settings, and accurately interpreting results against defined performance criteria. The structured approach to verification outlined in ISO 16140-3, built directly upon the vocabulary of Part 1, provides laboratories with a clear framework for demonstrating competence while maintaining flexibility to address their specific testing needs [19]. As microbiological testing technologies continue to advance, this standardized vocabulary will ensure that new methods can be evaluated consistently and implemented reliably, ultimately supporting the shared goal of enhanced product safety and public health protection.

Implementing ISO 16140-3: A Step-by-Step Protocol for Method Verification

Method verification is a critical requirement for laboratories accredited to ISO/IEC 17025, serving as a demonstration that a validated method can be performed competently within the user's laboratory [2]. The ISO 16140 series provides internationally recognized standards for the validation and verification of microbiological methods in the food and feed chain [1]. Within this framework, ISO 16140-3:2021 specifies the protocol for the verification of reference methods and validated alternative methods for implementation in the user laboratory [22]. This standard provides a structured, two-stage process that ensures a laboratory can correctly perform a method that has already been formally validated, confirming the method's performance characteristics within the specific laboratory environment [1] [2].

The verification process is fundamentally distinct from validation. Validation proves that a method is fit-for-purpose through interlaboratory studies, while verification demonstrates that a laboratory can satisfactorily perform a validated method [1]. This distinction is crucial for laboratories implementing methods for routine testing, as it provides objective evidence of competency and reliability [2].

The Two-Stage Verification Framework

ISO 16140-3:2021 outlines two sequential stages of verification that laboratories must complete before implementing a method for routine use [1]. These stages progress from confirming basic competency with the method to establishing performance across the laboratory's intended scope of testing.

Stage 1: Implementation Verification

Implementation verification serves as the initial proof of capability. Its purpose is to demonstrate that the user laboratory can perform the method correctly by obtaining results consistent with those established during the method's validation [1].

- Objective: To confirm technical competency in executing the method procedure

- Requirement: Testing one or more items that were previously characterized and used in the validation study

- Performance Criteria: Results must align with established reference values within defined acceptance criteria

This stage verifies that laboratory personnel, equipment, and environment can collectively reproduce the method's expected outcomes on known samples before proceeding to more challenging matrices.

Stage 2: Item Verification

Item verification expands the assessment to confirm method performance across the specific sample types routinely tested by the laboratory [1]. This stage addresses the reality that validation studies cannot practically test all possible sample matrices.

- Objective: To demonstrate method performance on challenging items within the laboratory's scope

- Requirement: Testing multiple food items representing the categories and types the laboratory typically analyzes

- Performance Characteristics: Evaluation against defined performance metrics relevant to the method type (detection, quantification, confirmation, or typing)

Item verification ensures the method produces reliable results for the specific applications required by the laboratory, even for sample types not explicitly included in the original validation study.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Qualitative Methods

For qualitative methods (detection), the verification focuses on accuracy, specificity, and limit of detection:

- Inoculation Studies: Use representative target organisms and related non-target strains

- Matrix Testing: Include a minimum of five food categories relevant to laboratory scope

- Control Requirements: Include positive, negative, and procedural controls in each run

- Data Analysis: Calculate relative accuracy, false positive, and false negative rates against reference method or known spike levels

Protocol for Quantitative Methods

For quantitative methods (enumeration), verification emphasizes accuracy, precision, and quantitation limit:

- Replicate Testing: Analyze multiple replicates at different contamination levels

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate mean, standard deviation, and relative standard deviation

- Comparison to Reference: Establish correlation with reference method results

- Acceptance Criteria: Demonstrate statistical equivalence within predefined limits

Protocol for Confirmation and Typing Methods

For confirmation and typing procedures, specific protocols apply as described in Clause 7 of ISO 16140-3 [1]:

- Strain Panel Testing: Use well-characterized target and non-target strains

- Comparative Analysis: Evaluate results against reference identification methods

- Specificity Assessment: Verify discrimination capability between related strains

Table 1: Key Performance Characteristics for Method Verification

| Method Type | Primary Characteristics | Secondary Characteristics | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | Relative Accuracy, Detection Limit | Specificity, False Positive/Negative Rates | ≥95% relative accuracy vs reference method |

| Quantitative | Mean, Standard Deviation, RSDr | Linearity, Quantitation Limit | RSDr ≤ reference method RSDR |

| Confirmation | Correct Identification Rate | Specificity, Discrimination Power | ≥90% correct identification |

Visualization of the Verification Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and sequential flow between the two stages of verification and their key outcomes:

Diagram 1: Two-Stage Verification Workflow

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Verification Studies

Successful execution of method verification requires specific materials and controls. The table below details essential research reagent solutions and their applications in verification studies:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Method Verification

| Reagent/Material | Function in Verification | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Strains | Positive controls for target organisms; establish method accuracy | ATCC/DSMZ strains for qualitative method detection limits |

| Chromogenic Media | Selective isolation and presumptive identification of target microbes | Detection of E. coli, coliforms, Salmonella in food matrices |

| Enrichment Broths | Promote growth of target organisms while inhibiting background flora | Buffered Peptone Water for Salmonella pre-enrichment |