Genomic SELEX: Unraveling Transcription Factor Binding Sites for Precision Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of genomic SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment), a powerful high-throughput method for identifying transcription factor (TF) binding specificities.

Genomic SELEX: Unraveling Transcription Factor Binding Sites for Precision Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of genomic SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment), a powerful high-throughput method for identifying transcription factor (TF) binding specificities. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of SELEX technology, detailing innovative methodological adaptations like HT-SELEX and Capillary Electrophoresis SELEX. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance motif discovery, and examines rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses against other platforms such as ChIP-seq. By synthesizing recent benchmarking studies and emerging computational models, this guide serves as a vital resource for advancing target-based therapeutic development and understanding gene regulatory networks.

The Foundation of Genomic SELEX: Principles and Technological Evolution

Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment (SELEX) is a combinatorial chemistry technique in molecular biology designed to produce single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides, known as aptamers, that specifically bind to a target ligand [1]. First introduced in 1990, the SELEX process enables the in vitro selection of nucleic acid molecules from vast random libraries through an iterative process of binding, selection, and amplification [2] [1]. Unlike biological systems that rely on cellular environments for antibody production, SELEX represents a fully in vitro evolution process that mimics natural selection at the molecular level, yielding affinity reagents with several advantages over traditional antibodies, including lower production costs, longer shelf-life, and reduced batch-to-batch variability [3].

The core principle of SELEX involves starting with an immensely diverse library of oligonucleotides, typically containing up to 10¹ⵠunique sequences, and through repeated rounds of selection pressure, enriching for progressively higher-affinity binders to a target of interest [1]. While the estimated success rate of traditional SELEX is below 30%, this can be significantly improved through specialized techniques, optimized libraries, and quality control procedures [3]. As the technology has matured, SELEX has expanded beyond basic molecular targets to include complex entities such as whole cells, subcellular structures, and has been adapted for high-throughput applications including transcription factor binding site identification [4] [5] [6].

Core Principles and Mechanisms

Fundamental SELEX Workflow

The SELEX process follows a systematic, iterative workflow that enables the evolution of nucleic acid sequences toward increasingly specific target binding. Each round of selection consists of several critical steps that collectively drive the enrichment process.

Molecular Interaction Mechanisms

The binding interactions between aptamers and their targets form the biochemical foundation of SELEX efficacy. These interactions are governed by several key mechanisms that vary depending on the relative size and properties of both the aptamer and target.

When aptamers are larger than their target, they typically integrate the target into their structure through stacking interactions (particularly with flat, aromatic ligands and ions), electrostatic complementarity (with oligosaccharides and charged amino acids), and hydrogen bond formation [3]. This mechanism is commonly observed with small molecule targets. Conversely, when the target is a large protein, the situation is generally reversed, with the aptamer being integrated into the target's structure or attaching to its surface [3].

The structural complexity of proteins enables more varied interaction mechanisms compared to small molecules, often involving combinations of hydrogen bonds, polar interactions, and structural complementarity [3]. Naturally occurring RNA- or DNA-binding motifs frequently exhibit such structural complementarity, including leucine zippers, homeodomains, helix motifs, and beta-sheet motifs [3]. The binding event itself can involve conformational changes in either the target, the aptamer, or both according to the "induced fit" principle, resulting in improved shape complementarity that facilitates short-range interactions including hydrogen bonds and van der Waals contacts [3].

The physicochemical properties of both target and aptamer significantly influence binding efficacy. Negative charges on a target molecule's surface can weaken or prevent aptamer binding due to unfavorable interactions with the electronegative phosphate groups in DNA and RNA backbones [3]. Conversely, positive charges can enhance interaction strength but may also increase nonspecific binding [3]. Largely hydrophobic molecules present particular challenges as aptamers are generally hydrophilic, though this limitation can be addressed through incorporation of modified nucleotides [3].

Key SELEX Variants and Their Applications

As SELEX technology has evolved, numerous specialized variants have been developed to address specific research needs and target types. The table below summarizes the principal SELEX variants and their characteristics.

Table 1: Key SELEX Variants and Their Applications

| SELEX Variant | Target Type | Selection Methodology | Primary Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic SELEX [4] | Genomic DNA fragments | Selection using fragmented genomic DNA instead of random oligonucleotides | Transcription factor binding site identification, regulatory network mapping | Identifies biologically relevant binding sites within native genomic context |

| Cell-SELEX [2] [5] | Whole living cells | Iterative selection using intact cells as targets | Cancer cell identification, drug delivery, in vivo diagnostics | Preserves native conformation of cell surface targets; no prior knowledge of membrane proteins required |

| High-Throughput SELEX (HT-SELEX) [6] | Proteins, small molecules | Combines SELEX with next-generation sequencing | Comprehensive binding specificity profiling, transcription factor specificity determination | Enables parallel analysis of multiple targets; provides quantitative binding data |

| Filter-Based SELEX [3] [1] | Proteins, large molecules | Target immobilization on nitrocellulose filters | Protein-aptamer interaction studies | Simple, affordable methodology |

| Bead-Based SELEX [3] | Proteins, small molecules, cells | Target coupling to magnetic or chromatographic beads | Small molecule aptamer selection, clinical diagnostics | Versatile target options; easy separation using magnets or centrifugation |

Genomic SELEX for Transcription Factor Binding Site Identification

Genomic SELEX represents a powerful adaptation of the traditional method that replaces synthetic random oligonucleotide libraries with fragments of actual genomic DNA [4]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying transcription factor binding sites and mapping gene regulatory networks. In vertebrate systems, genomic SELEX has successfully identified transcription factor targets by isolating genomic fragments bound by specific DNA-binding proteins like Fezf2, a conserved zinc finger protein critical for forebrain development [4].

The fundamental advantage of genomic SELEX lies in its ability to identify binding sites within their native genomic context, revealing both known and unexpected regulatory elements. For instance, applications in zebrafish demonstrated that approximately 20% of Fezf2-bound fragments overlapped with well-annotated protein-coding exons, suggesting additional regulatory functions [4]. This approach circumvents limitations of chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-based methods, which require ChIP-quality antibodies and abundant factor expression in relevant cell types [4].

The genomic SELEX protocol typically involves digesting genomic DNA with restriction enzymes (e.g., Sau3A1), incubating fragments with the transcription factor of interest, and performing multiple rounds of selection and amplification [4]. Computational analysis of bound sequences identifies enriched motifs and consensus binding sites, which can be validated through biochemical assays, reporter constructs, and in vivo models [4].

Experimental Protocols

Standard Genomic SELEX Protocol

This protocol details the application of genomic SELEX for identification of transcription factor binding sites, adapted from established methodologies [4].

Reagent Preparation

- Transcription Factor: Purified DNA-binding domain of transcription factor (e.g., GST-tagged zinc finger domain)

- Genomic DNA: High-molecular-weight genomic DNA (20 μg per selection round)

- Restriction Enzyme: Sau3A1 or appropriate restriction enzyme for genomic fragmentation

- Binding Buffer: 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 0.05% NP-40

- PCR Components: Taq polymerase, dNTPs, adapter primers

- Solid Support: Glutathione sepharose beads for GST-tagged proteins

Step-by-Step Procedure

Genomic DNA Fragmentation

- Digest 20 μg genomic DNA with Sau3A1 (or appropriate restriction enzyme) for 2 hours at 37°C

- Verify fragmentation by agarose gel electrophoresis (target range: 100-500 bp)

- Purify fragments using silica membrane columns

Transcription Factor Immobilization

- Incubate purified GST-tagged transcription factor domain with glutathione sepharose beads for 1 hour at 4°C

- Wash beads three times with binding buffer to remove unbound protein

- Quantify bound protein using Bradford assay

First Selection Round

- Incubate immobilized transcription factor with fragmented genomic DNA in binding buffer for 30 minutes at room temperature

- Wash protein-DNA complexes five times with binding buffer to remove non-specifically bound DNA

- Elute specifically bound DNA fragments with elution buffer (10 mM glutathione, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0)

PCR Amplification

- Ligate eluted DNA fragments with adapter sequences using T4 DNA ligase

- Amplify adapter-ligated fragments using PCR with the following conditions:

- 94°C for 3 minutes (initial denaturation)

- 25 cycles of: 94°C for 30s, 55°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s

- 72°C for 5 minutes (final extension)

- Purify PCR products using silica membrane columns

Subsequent Selection Rounds

- Repeat steps 3-4 for 3-4 additional rounds with increased stringency:

- Increase number of washes in each subsequent round

- Add non-specific competitor DNA (e.g., poly(dI-dC)) in later rounds

- Monitor enrichment by measuring DNA recovery after each round

- Repeat steps 3-4 for 3-4 additional rounds with increased stringency:

Clone and Sequence

- Clone final-round PCR products into sequencing vector

- Sequence 50-100 clones from final round using Sanger sequencing

- Alternatively, subject final pool to high-throughput sequencing

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting

- Protein Quality: Ensure transcription factor preparation is >90% pure and properly folded

- Stringency Control: Increase washing stringency gradually to avoid loss of specific binders early in process

- Amplification Bias: Limit PCR cycles to minimize amplification bias; monitor reaction efficiency

- Background Binding: Include control selections with beads alone to identify background binders

High-Throughput Sequencing SELEX (HT-SELEX) Protocol

HT-SELEX combines traditional selection with next-generation sequencing to comprehensively characterize binding specificities [6].

Procedure Modifications for HT-SELEX

Library Preparation

- Use random oligonucleotide library with fixed flanking sequences for amplification

- Include sequencing adapters compatible with Illumina platforms during initial library construction

Selection Process

- Perform 5-8 rounds of selection with constant protein concentration to maintain fixed stringency

- Retain aliquots from each selection round for sequencing to monitor evolution

Sequencing Library Preparation

- Amplify selected pools from multiple rounds using barcoded primers

- Pool amplified products from different rounds for multiplex sequencing

- Sequence on Illumina platform to obtain >1 million reads per sample

Bioinformatic Analysis

- Use specialized pipelines (e.g., eme_selex) to identify enriched k-mers

- Calculate enrichment ratios for all possible k-mers across selection rounds

- Generate position weight matrices from enriched sequences

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Analysis of SELEX Data

The analysis of SELEX data has evolved from simple consensus identification to sophisticated quantitative modeling. Modern approaches enable accurate determination of protein-DNA interaction parameters, providing insights into binding specificity and affinity.

Table 2: Key Parameters in SELEX Data Analysis

| Parameter | Description | Calculation Method | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Ratio | Relative abundance of sequence between rounds | (Frequencyroundn)/(Frequencyroundn-1) | Identifies sequences under positive selection |

| K-mer Enrichment | Enrichment of all possible sequences of length k | Normalized count compared to expected frequency | Reveals core binding motifs without assumptions |

| Position Weight Matrix (PWM) | Quantitative representation of binding preferences | Log-likelihood ratios for each base at each position | Enables prediction of binding sites in genomic sequences |

| Dissociation Constant (Kd) | Measure of binding affinity | Determined from fixed-stringency SELEX experiments | Provides quantitative affinity measurements for individual sequences |

Quantitative modeling of SELEX experiments has revealed limitations in traditional approaches for determining protein-DNA interaction parameters [7]. A modified approach maintaining fixed chemical potential (constant free protein concentration) through different selection rounds enables more robust parameter estimation [7]. This fixed-stringency approach generates datasets from which binding energies can be accurately derived, significantly improving the false positive/false negative trade-off compared to traditional methods [7].

For genomic SELEX, computational analysis typically involves multiple motif-finding algorithms (BioProspector, AlignACE, MEME) to identify sequence motifs enriched in selected fragments compared to genomic background [4]. Additional analyses include conservation assessment across species and genomic annotation of selected fragments to identify potential regulatory regions [4].

Validation of Selected Aptamers and Binding Sites

Identification of potential binders through SELEX requires rigorous validation to confirm specificity and biological relevance:

In Vitro Binding Assays

- Fluorescence anisotropy to determine dissociation constants (Kd)

- Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) to confirm direct binding

- Competition assays to assess binding specificity

Functional Validation

- Reporter gene assays with selected sequences cloned upstream of minimal promoters

- Site-directed mutagenesis of predicted binding sites to confirm specificity

- Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to confirm in vivo binding [4]

Biological Validation

- Loss-of-function studies (e.g., morpholino knockdown) to assess functional consequences

- Gain-of-function experiments to test sufficiency

- Correlation with gene expression changes in relevant biological systems [4]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful SELEX experiments require carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for each selection target and methodology.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SELEX Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Selection Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligonucleotide Library | Random ssDNA/RNA library with 20-60 nt variable region | Provides sequence diversity for selection | Library complexity should exceed 10¹³ sequences; structural diversity critical |

| Target Molecules | Purified proteins, small molecules, whole cells | Binding target for selection | Purity, conformation, and immobilization method affect selection outcome |

| Immobilization Matrix | Glutathione sepharose, streptavidin beads, nitrocellulose filters | Enables separation of bound and unbound sequences | Matrix should not interfere with target structure or introduce nonspecific binding |

| Amplification Reagents | Taq polymerase, dNTPs, primers with adapter sequences | Amplifies selected sequences for subsequent rounds | Primer design critical to avoid dimerization; polymerase fidelity affects diversity |

| ssDNA Generation | Biotinylated primers, streptavidin beads, lambda exonuclease | Regenerates single-stranded DNA for selection rounds | Efficiency critical; different methods yield 50-70% recovery [1] |

| Buffer Components | Salts, competitors (e.g., poly(dI-dC)), nuclease inhibitors | Creates optimal binding environment | Ionic strength affects electrostatic interactions; competitors reduce background |

| Unesbulin | 5-Fluoro-2-(6-fluoro-2-methyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)-N4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)pyrimidine-4,6-diamine | High-purity 5-Fluoro-2-(6-fluoro-2-methyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)-N4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)pyrimidine-4,6-diamine for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| (R)-Azelastine Hydrochloride | (R)-Azelastine Hydrochloride, CAS:153408-28-7, MF:C22H25Cl2N3O, MW:418.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Critical Factors and Optimization Strategies

Several factors significantly influence SELEX success and require careful optimization:

Target Considerations

The nature of the target molecule profoundly impacts selection strategy and expected outcomes. Protein targets require consideration of surface charges, as strongly negative surfaces may repel nucleic acids, while positive charges may promote nonspecific binding [3]. Small molecules necessitate careful immobilization to ensure presentation of appropriate epitopes for binding [3]. For transcription factors, using the DNA-binding domain rather than full-length protein often improves selection efficiency [4].

Library Design

Library complexity directly influences selection success. The sequence diversity should significantly exceed the total number of sequences used in the first selection round to ensure adequate structural diversity [3]. Constant domains and primers should be optimized to minimize structural influence on the random region and prevent primer-dimer formation [3]. For specialized applications, chemically modified nucleotides (e.g., 2'-F, 2'-O-methyl RNA) can enhance stability and introduce novel chemical functionalities [1].

Selection Stringency

Appropriate stringency control is essential for successful SELEX. Early rounds should employ lower stringency to avoid losing rare potential binders, while later rounds require progressively increased stringency to eliminate moderate-affinity binders and drive selection toward optimal sequences [3]. Stringency can be modulated through various parameters:

- Wash conditions: Increasing wash volume, duration, or number

- Competitor DNA: Adding nonspecific DNA (e.g., salmon sperm DNA) to compete weak binders

- Salt concentration: Modifying ionic strength to alter binding stringency

- Incubation time: Reducing time to select for faster binding kinetics

Quality Control and Monitoring

Implementing quality control measures throughout the selection process enables informed decisions about progression and termination. Key monitoring approaches include:

- Binding yield: Tracking the percentage of library bound to target each round

- Sequence diversity: Monitoring complexity reduction through clone sequencing or HTS

- Progress assessment: Using specific binding assays to confirm enrichment of target-specific binders

- By-product detection: Identifying amplification artifacts (e.g., primer-dimers) early

SELEX technology represents a powerful platform for generating specific nucleic acid ligands against diverse targets, with genomic SELEX providing particularly valuable insights into transcription factor binding specificities and regulatory networks. The core principles of iterative selection and amplification enable the evolution of high-affinity binders from highly diverse starting libraries. Successful application requires careful consideration of multiple factors, including target presentation, library design, stringency control, and appropriate analytical methods. As SELEX methodologies continue to evolve, particularly with integration of high-throughput sequencing and sophisticated bioinformatic analysis, the applications in basic research, diagnostic development, and therapeutic discovery continue to expand. The protocols and considerations outlined here provide a foundation for designing effective SELEX experiments aimed at identifying specific binding sequences, particularly in the context of transcription factor binding site identification.

HT-SELEX as a High-Throughput Platform for TF Binding Profiling

High-Throughput Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (HT-SELEX) has emerged as a powerful in vitro technique for unbiased determination of DNA binding specificities of transcription factors (TFs). This method enables researchers to characterize preferred target motifs by selecting protein-binding DNA sequences from a vast random oligonucleotide library through iterative cycles of binding, purification, and amplification [8]. Unlike in vivo methods like ChIP-seq, which are constrained by cellular contexts and antibody availability, HT-SELEX provides a controlled environment to explore TF-DNA interactions systematically, making it particularly valuable for profiling poorly studied human transcription factors [9] [10].

The fundamental advantage of HT-SELEX lies in its ability to process thousands to millions of DNA sequences in a single experiment, generating massive datasets that comprehensively capture TF binding preferences [10]. This technological advancement addresses a critical bottleneck in regulatory genomics, as traditional low-throughput methods yielded insufficient data for building accurate models of transcription factor binding sites. Current datasets now encompass hundreds of TF experiments, enabling computational biologists to develop more sophisticated models of DNA recognition beyond simple position weight matrices [11] [10].

Performance and Benchmarking of HT-SELEX

Cross-Platform Performance Assessment

Recent large-scale benchmarking initiatives have evaluated HT-SELEX alongside other prominent technologies for TF binding characterization. The Gene Regulation Consortium Benchmarking Initiative (GRECO-BIT) analyzed an extensive collection of 4,237 experiments for 394 TFs using five different experimental platforms, including HT-SELEX, ChIP-Seq, genomic HT-SELEX (GHT-SELEX), SMiLE-Seq, and PBMs [9].

This systematic comparison revealed that motif consistency across platforms and replicates serves as a key quality metric for successful experiments. Through rigorous human curation, researchers approved a subset of experiments that yielded reliable motifs, with 236 TFs ultimately represented in the high-quality dataset of 1,462 approved experiments [9]. The study demonstrated that motifs with low information content in many cases effectively described binding specificity across different experimental platforms, challenging previous assumptions about motif quality assessment.

Table 1: Comparison of Experimental Platforms for TF Binding Characterization

| Platform | Library Type | Context | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT-SELEX | Synthetic random oligonucleotides | In vitro | Unbiased exploration of sequence space; massive throughput | May saturate with strongest binders; lacks cellular context |

| GHT-SELEX | Genomic DNA fragments | In vitro | Natural sequence variation; biochemical environment | Limited to genomic regions in library |

| ChIP-Seq | Genomic regions | In vivo | Native chromatin context; actual binding locations | Antibody-dependent; broad footprints; cellular constraints |

| PBM | Pre-designed probes | In vitro | Highly quantitative; comprehensive probe coverage | Fixed probe sequences; may miss novel motifs |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The benchmarking effort generated an impressive 219,939 position weight matrices (PWMs), with 164,570 derived from approved experiments [9]. After automatic filtering for common artifact signals (such as simple repeats and widespread ChIP contaminants), 159,063 high-quality PWMs were obtained. The evaluation employed multiple dockerized benchmarking protocols with different scoring methods:

- Sum-occupancy scoring for most sequence types

- Single top-scoring log-odds PWM hit evaluation for ChIP-Seq and GHT-SELEX peaks

- CentriMo motif centrality score accounting for distance to peak summit [9]

Notably, the study found that nucleotide composition and information content did not correlate with motif performance and failed to help in detecting underperformers. This finding challenges conventional wisdom in the field and suggests the need for more sophisticated metrics in assessing motif quality [9].

HT-SELEX Experimental Protocol

The HT-SELEX method follows an iterative selection-amplification process that enriches protein-binding DNA sequences from a random library. The key steps include:

- Library Preparation: Generation of double-stranded DNA oligonucleotides containing random regions flanked by constant sequences for PCR amplification

- Binding Reaction: Incubation of the DNA library with purified, tagged transcription factor

- Partitioning: Separation of protein-DNA complexes from unbound DNA

- Amplification: PCR enrichment of bound sequences for the next selection cycle

- Sequencing: High-throughput sequencing of selected pools, typically after multiple cycles [8] [11]

The process typically requires 3-5 cycles to sufficiently enrich for high-affinity binders, though excessive cycles can reduce library diversity and bias results toward the strongest binding sequences [9] [8].

Detailed Step-by-Step Methodology

Generate Random Library of Double-Stranded DNA Oligonucleotides (Cycle 0)

The initial library consists of synthetic oligonucleotides with a central random region (typically 20-40 bp) flanked by constant sequences that serve as PCR primer binding sites. Technical replicates using three separate random oligonucleotide libraries are recommended to account for distribution variations [8].

Table 2: PCR Mastermix for Library Preparation (24 reactions)

| Reagent | Amount per Mastermix | Final Concentration | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random library DNA template | 12 pmol (0.5 pmol/reaction) | Variable | Provides diverse starting sequences |

| 5× Phusion HF Buffer | 240 μL | 1× | Optimal reaction conditions |

| dNTPs (10 mM) | 24 μL | 200 μM each | DNA synthesis building blocks |

| Library FW Primer (10 μM) | 60 μL | 0.5 μM | Forward amplification primer |

| Library RV Primer (10 μM) | 60 μL | 0.5 μM | Reverse amplification primer |

| Phusion DNA Polymerase | 12 μL | 0.02 U/μL | High-fidelity DNA amplification |

| Nuclease-free water | Up to 1.2 mL | - | Reaction volume adjustment |

PCR Program for Library Amplification:

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 1 min (1 cycle)

- Denaturation: 98°C for 20 s

- Annealing: 60°C for 20 s (5 cycles)

- Extension: 72°C for 20 s

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 min (1 cycle)

- Hold: 4°C indefinitely [8]

After amplification, the double-stranded DNA libraries are purified using commercial PCR purification kits (e.g., Qiagen MinElute), with concentration and integrity assessed via spectrophotometry. A single band at approximately 83 bp should be visible on a 10% polyacrylamide gel without detectable heteroduplexes [8].

Protein Purification and Binding Reactions

The success of HT-SELEX depends critically on the quality and purity of the transcription factor. While protocols vary by specific TF, these general principles apply:

- Affinity Tags: His-tag, GST, or other affinity tags enable both protein purification and isolation of protein-DNA complexes

- Expression Systems: E. coli, wheat germ extracts, or mammalian systems selected based on TF requirements

- Buffer Optimization: Conditions must maintain TF stability and DNA-binding capability [8]

For the binding reaction, recombinant TF (e.g., 0.5 mg/mL concentration) is incubated with the DNA library in appropriate binding buffer. Poly(dI-dC) is often included as non-specific competitor DNA. Complexes are isolated using affinity resin corresponding to the protein tag (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins) [8].

After binding and washing, protein-DNA complexes are eluted, and bound DNA is amplified for subsequent cycles or prepared for sequencing after the final round. Modern implementations typically use 3-4 selection cycles before high-throughput sequencing [8] [11].

Computational Analysis of HT-SELEX Data

Bioinformatics Pipeline

The massive datasets generated by HT-SELEX require sophisticated computational analysis. A typical bioinformatics pipeline includes:

- Sequence Processing: Quality control, demultiplexing, and parsing of sequencing reads

- Enrichment Analysis: Identification of significantly enriched k-mers across selection cycles

- Motif Discovery: Application of algorithms to infer binding motifs from enriched sequences

- Model Building: Construction of quantitative models representing TF binding preferences [8] [10]

The eme_selex pipeline facilitates detection of promiscuous DNA binding by analyzing enrichment of all possible k-mers, providing a comprehensive view of sequence preferences [8].

Advanced Modeling Approaches

While Position Weight Matrices (PWMs) remain the most common representation of binding motifs, their assumption of position independence represents a significant limitation. Recent advances include:

- DCA-Scapes: A global pairwise model that captures interdependencies between nucleotide positions, providing higher-resolution TF recognition specificity landscapes [10]

- Random Forest Models: Combining multiple PWMs to account for multiple modes of TF binding, demonstrating improved performance over single motifs [9]

- Hamiltonian Scoring: A quantitative approach that predicts the likelihood of DNA sequences being TF targets, with more negative scores indicating stronger binding [10]

These advanced models have demonstrated superior performance in predicting in vivo binding sites validated by ChIP-seq data, with Hamiltonian scores showing significant discrimination between bound and unbound genomic regions [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for HT-SELEX

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Oligo Library | 20-40 bp random region with constant flanks | Source of diverse DNA sequences for selection | Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Phusion or equivalent | Error-free amplification of selected sequences | New England Biolabs (NEB) |

| Affinity Purification Resin | Ni-NTA, glutathione, or antibody-conjugated | Isolation of protein-DNA complexes | Cytiva, Qiagen |

| Tagged Recombinant TF | His-tag, GST, or other affinity tag | DNA-binding protein for selection | In-house expression or commercial |

| Poly(dI-dC) | Non-specific competitor DNA | Reduction of non-specific binding | Merck Life Science |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Platform | Illumina or equivalent | High-throughput readout of selected sequences | Various providers |

| Bioinformatics Tools | HOMER, MEME, STREME, RCade, DCA-Scapes | Motif discovery and data analysis | Publicly available packages |

Transcription factor (TF) binding to DNA is a fundamental component of transcriptional regulation, responsible for coordinated gene expression within gene regulatory networks [9]. The accurate identification of DNA sequences recognized by TFs—their binding motifs—is crucial for annotating gene regulatory regions, interpreting regulatory variation, and deciphering the logic of gene regulatory networks [9]. A sequence motif representing the DNA-binding specificity of a TF is commonly modeled with a positional weight matrix (PWM) [9]. However, generating accurate motif models is challenging due to technical biases inherent in different experimental platforms, which influence the types of binding sites detected and the resulting biological interpretations.

The binding specificity of a TF ideally should be studied both in vivo and in vitro with both synthetic and genomic sequences, using multiple experimental platforms to overcome these inherent challenges [9]. This Application Note examines the technical characteristics, advantages, and limitations of major experimental platforms used for TF binding site identification, with a special focus on Genomic SELEX and its variants within the broader context of TF research. We provide detailed protocols and analytical frameworks to help researchers select appropriate methodologies, mitigate technical biases, and integrate complementary data sources for a more comprehensive understanding of TF-DNA interactions.

Experimental Platforms: Comparative Analysis

Multiple experimental platforms have been developed to identify TFBS in random sequences, complete genomes, or their fragments [9]. These can be broadly categorized into in vitro methods using synthetic DNA sequences and in vivo methods examining binding in cellular contexts. Table 1 summarizes the key experimental platforms, their underlying principles, and the types of biases inherent in each approach.

Table 1: Comparison of Experimental Platforms for TF Binding Site Identification

| Platform | Principle | DNA Source | Key Strengths | Technical Biases/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT-SELEX [9] [12] | Multiple rounds of in vitro selection and amplification | Synthetic random oligos | High-throughput; models for hundreds of TFs; identifies high-affinity sites | Rapid saturation with strongest binders; misses lower-affinity sites; over-representation of high-affinity sites |

| Genomic SELEX (GHT-SELEX) [13] [9] | SELEX with genomic DNA fragments | Natural genomic DNA | Discovers natural genomic aptamers; identifies binding domains in native context | Limited to accessible genomic regions; depends on library representation |

| ChIP-Seq [9] [10] | Chromatin immunoprecipitation with sequencing | Cellular genomic DNA | In vivo binding context; includes chromatin effects | Requires ChIP-grade antibodies; broad footprints; influenced by cellular environment |

| PADIT-seq [12] | In vitro transcription coupled to reporter output | All possible k-mers (e.g., all 10-mers) | Unprecedented sensitivity for low-affinity sites; quantitative affinity measurements | Newer method with less established benchmarks; specialized protocol |

| PBM [9] [12] | Protein binding to microarrayed DNA probes | Pre-defined synthetic sequences | Comprehensive k-mer binding data; high reproducibility | Fixed probe design limits sequence space; potential flanking sequence effects |

| SMiLE-Seq [9] | Microfluidics-based ligand enrichment | Synthetic random sequences | Efficient selection; requires fewer rounds | Platform-specific biases not fully characterized |

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Platforms

Different platforms exhibit varying capabilities to detect binding sites across affinity ranges. Recent comparative studies, particularly the Gene Regulation Consortium Benchmarking Initiative (GRECO-BIT), have quantitatively evaluated platform performance [9]. Table 2 presents key performance metrics for major platforms based on cross-platform benchmarking studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of TF Binding Assay Platforms

| Platform | Affinity Range Detected | Sequence Coverage | Sensitivity to Low-Affinity Sites | Correlation with Functional Binding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT-SELEX | High-affinity (Kd < 0.01 μM) [12] | Moderate (107-108 sequences) [9] | Limited (AUROC ~0.7-0.8) [12] | Moderate; biased toward strongest binders |

| PADIT-seq | Broad (Kd ~ 0.1 μM to high affinity) [12] | Comprehensive (all 10-mers) [12] | Excellent (detects hundreds of low-affinity sites) [12] | Strong; correlates with MITOMI Kd (r > 0.9) [12] |

| PBM | Moderate to high affinity [12] | Fixed design (all 8-9mers with flanks) [12] | Moderate (misses lower-affinity sites with E-score < 0.3) [12] | Good for high-affinity sites; variable thresholds by TF |

| ChIP-Seq | In vivo relevant affinities | Genome-wide | Context-dependent | High for in vivo binding but confounded by cellular factors |

| GHT-SELEX | Moderate to high affinity | Depends on genomic library | Better than HT-SELEX for genomic context | Good balance of in vitro and genomic context |

Detailed Methodologies

Genomic SELEX Protocol

Genomic SELEX is a discovery tool for genomic aptamers, which are genomically encoded functional domains in nucleic acid molecules that recognize and bind specific ligands [13]. The major difference between SELEX and Genomic SELEX is the starting pool: while traditional SELEX begins with a library of synthetically derived random DNA molecules, Genomic SELEX starts from libraries derived from genomic DNA [13].

Library Construction and Selection

- Source DNA Preparation: Obtain high-quality genomic DNA from an organism with a fully sequenced genome to allow mapping and analysis of selected sequences [13].

- Primer Design: Design two pairs of primers called "hyb"- and "fix"-primers [13].

- hyb-primers consist of a unique constant sequence region absent in the genome, followed by approximately 9 randomized nucleotides at the 3' terminus

- fix-primers correspond perfectly to the 5' constant regions of respective hyb-primers, with addition of the T7 promoter at the 5' end of the fixFOR primer

- Library Amplification: Perform first- and second-strand Klenow synthesis using hybREV and hybFOR primers, respectively [13].

- Bait Preparation: Use purified RNA-binding proteins as bait. Purity is crucial to avoid enrichment of aptamers binding contaminants [13]. Translational fusion to different tags (e.g., His, Flag or GST) can facilitate purification [13].

- Selection Procedure: Incubate the DNA library with the bait protein. Separate protein-DNA complexes from unbound DNA using methods appropriate for the tag (e.g., glutathione Sepharose for GST-tagged proteins) [14].

- Washing and Elution: Wash thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound DNA. Elute specifically bound DNA [14].

- Amplification and Repeated Selection: Amplify eluted DNA and subject to additional rounds of selection (typically 2-4 rounds) to enrich specific binders [14] [13].

Counter-Selection and Controls

- Counter-Selection: Use modified or inactive baits to strengthen binding specificity of selected sequences [13].

- Neutral SELEX Control: Perform a "Neutral" SELEX experiment in parallel, omitting the selection step, to provide a background signal for comparison [13].

- Sequence Blocking: To prevent flanking primers from becoming part of the structural motif, especially with short libraries, anneal oligonucleotides complementary to flanking regions prior to selection or switch flanking sequences every few SELEX cycles [13].

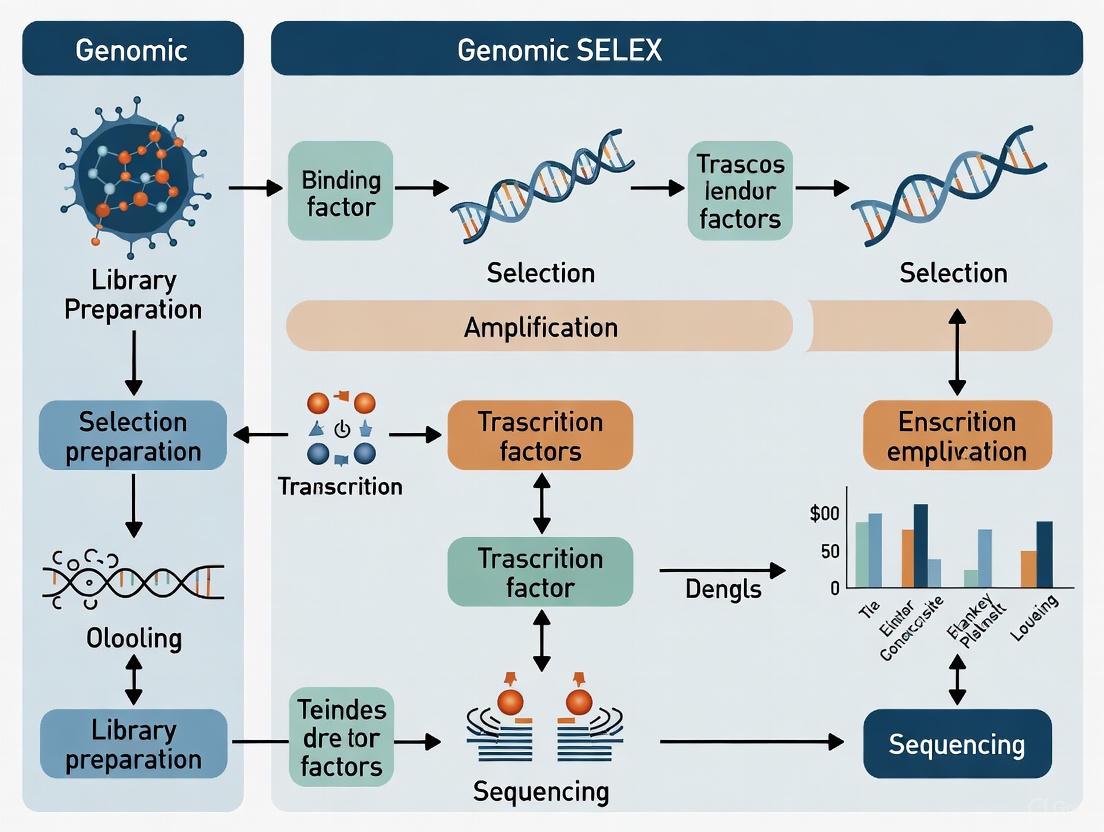

Genomic SELEX Workflow

Affinity Chromatography-SELEX with Quantitative Binding Assay

Combining affinity chromatography-SELEX with quantitative binding assays provides a streamlined approach to generate accurate models of TF binding specificity [14].

Affinity Chromatography-SELEX Procedure

- Protein Preparation: Express GST-tagged DNA-binding domain (e.g., GST-Zif268) in E. coli and purify using glutathione Sepharose chromatography [14].

- DNA Pool Design: Create double-stranded DNA pool containing random regions flanked by fixed sequences for PCR amplification and cloning [14].

- Binding Reaction: Incubate DNA pool (~10â»â¸ M) with purified GST-tagged protein (~10â»â¸ M) in reaction buffer [30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 3 mM DTT, 20 µM ZnSOâ‚„, 25 µg/ml salmon sperm DNA] for 1 hour at room temperature [14].

- Affinity Capture: Add glutathione Sepharose slurry to capture protein-DNA complexes. Wash thoroughly with reaction buffer [14].

- Elution and Amplification: Elute bound DNA with elution buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 0.25 M KCl, 10 mM glutathione]. Amplify eluted DNA by PCR for subsequent selection rounds [14].

- Cloning and Sequencing: After 2-4 selection rounds, clone isolated DNA sites into sequencing vector and sequence individual clones [14].

Quantitative Multiplex Fluorescence Relative Affinity (QuMFRA) Assay

- Fluorescent Labeling: Generate double-stranded oligonucleotide binding sites by PCR using fluorophore-labeled primers (FAM, TAMRA, or ROX) [14].

- Competitive Binding: Mix three different fluorophore-labeled DNA binding sites with GST-tagged protein (~10â»â¸ M) in reaction buffer [14].

- Electrophoretic Separation: Separate protein-DNA complexes from free DNA by electrophoresis on 10% polyacrylamide gel [14].

- Fluorescence Detection: Scan gels using a fluorescence scanner (e.g., Typhoon Variable Scanner) to obtain fluorescent intensities at different emission wavelengths [14].

Relative Affinity Calculation: Calculate relative binding constant using the formula:

[ Ka(rel) = \frac{[PD{test}][D{ref}]}{[PD{ref}][D_{test}]} ]

where [PDtest] and [PDref] are concentrations of bound DNA for test and reference sites, and [Dtest] and [Dref] are concentrations of free DNA [14].

PADIT-seq Protocol for Comprehensive Affinity Measurement

PADIT-seq (Protein Affinity to DNA by In Vitro Transcription and RNA sequencing) is a recently developed technology that measures TF-DNA binding preferences at greater sensitivity than prior high-throughput methods, particularly for lower affinity interactions [12].

Reporter Library Construction

- Library Design: Construct a reporter library containing all possible 10-bp DNA sequences (n = 1,048,576) as candidate TF binding sites [12].

- Barcode Association: Randomly associate TF binding sites with barcodes during library construction and determine TFBS-barcode combinations by Illumina sequencing [12].

Binding Assay and Sequencing

- In Vitro Transcription and Translation: Mix PADIT-seq reporter library with either a 'no DBD' control or a constitutive promoter driving expression of the DNA-binding domain of interest [12].

- Reporter RNA Sequencing: Following IVTT, sequence reporter RNAs by Illumina sequencing [12].

- Differential Analysis: Perform differential gene expression analysis of TFBS counts against the 'no DBD' control using DESeq2 [12].

- Activity Calculation: Define logâ‚‚(DBD / 'no-DBD') values as 'PADIT-seq activity,' with 'active' TFBS defined as those significantly increasing reporter gene expression upon TF binding (FDR 5%) [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Genomic SELEX and TF Binding Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pGEX-4T-1 (GST-tag), pET series | Recombinant protein expression with affinity tags for purification [14] |

| Affinity Matrices | Glutathione Sepharose, Nickel-NTA, Antibody-conjugated beads | Capture and purification of tagged proteins or protein-DNA complexes [14] [13] |

| DNA Library Templates | Random oligo pools, Genomic DNA fragments | Source of potential binding sites for selection experiments [14] [13] |

| Amplification Reagents | High-fidelity DNA polymerases, dNTPs, Fluorophore-labeled primers | Amplification of selected DNA pools; preparation of labeled probes [14] |

| Binding Assay Components | BSA, carrier DNA (salmon sperm), DTT, ZnSOâ‚„ (for zinc fingers) | Reduction of non-specific binding in reaction buffers [14] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina for high-throughput, Sanger for individual clones | Identification of selected sequences; determination of binding motifs [14] [13] |

| Relamorelin | Relamorelin, CAS:661472-41-9, MF:C43H50N8O5S, MW:791.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Remodelin hydrobromide | Remodelin hydrobromide, MF:C15H15BrN4S, MW:363.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Data Analysis and Computational Modeling

Motif Discovery and Benchmarking

With diverse experimental platforms generating TF binding data, appropriate computational analysis is essential for deriving accurate motif models. The GRECO-BIT initiative has systematically evaluated motif discovery tools across multiple experimental platforms [9].

- Data Preprocessing: Uniformly preprocess data, including peak calling for GHT-SELEX and ChIP-Seq data, and normalization for PBMs [9].

- Training-Test Split: Split results of each experiment into training and test sets for validation [9].

- Motif Discovery Tools: Apply multiple motif discovery tools compatible with different data types:

- Benchmarking Protocols: Employ multiple benchmarking protocols using sum-occupancy scoring, HOCOMOCO benchmark (single top-scoring hit), and CentriMo motif centrality score [9].

- Expert Curation: Manually curate results to approve experiments that yield consistent motifs across platforms or similar to known motifs [9].

Advanced Modeling Approaches

Moving beyond standard position weight matrices can improve characterization of TF binding specificities:

- DCA-Scapes Model: A global pairwise model that captures interdependencies between nucleotide positions in TF binding sites, providing higher resolution TF recognition specificity landscapes [10].

- Hamiltonian Scoring: For a given DNA sequence, the Hamiltonian score quantitatively predicts the likelihood of it being a TF target, with more negative scores indicating greater likelihood of favorable TF recognition [10].

- Random Forest Approaches: Combining multiple PWMs into a random forest accounts for multiple modes of TF binding and improves binding prediction [9].

Computational Analysis Workflow

Understanding and addressing technical biases in experimental platforms for TF binding site identification is crucial for generating accurate biological insights. As demonstrated through comparative analyses, each platform possesses distinct strengths and limitations in detecting binding sites across the affinity spectrum [9] [12]. HT-SELEX efficiently identifies high-affinity sites but saturates quickly and misses lower-affinity interactions [12], while newer technologies like PADIT-seq offer unprecedented sensitivity for detecting lower-affinity sites but require specialized expertise [12].

The integration of multiple experimental approaches—combining in vitro and in vivo methods, synthetic and genomic DNA sources—provides the most comprehensive characterization of TF binding specificities [9]. Furthermore, advanced computational models that move beyond simple position weight matrices to account for nucleotide interdependencies and multiple binding modes promise to extract more biological insight from experimental data [9] [10].

As the field advances, researchers should select experimental platforms based on their specific biological questions, employ appropriate controls to address platform-specific biases, and integrate complementary data sources to develop accurate models of TF-DNA interactions that reflect the complexity of gene regulatory systems.

The Role of SELEX in Profiling Poorly Studied and Novel Transcription Factors

The comprehensive characterization of transcription factor (TF) binding specificities is a fundamental challenge in molecular biology, particularly for poorly studied and novel TFs. DNA–transcription factor interactions are essential for gene regulation, and fully characterizing TF recognition specificities is critical to understanding TF function and regulatory networks [10]. Among the various techniques available, the Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) method has emerged as a particularly powerful in vitro approach for determining the binding preferences of TFs, even in the absence of prior biological knowledge [14]. Recent advancements have seen the evolution of SELEX into High-Throughput SELEX (HT-SELEX), which combines the biochemical robustness of traditional SELEX with the scale of modern sequencing technology [15]. This protocol outlines detailed methodologies for employing SELEX and HT-SELEX to profile novel TFs, framed within the broader context of genomic SELEX research, and provides the necessary tools for researchers to identify TF binding motifs with high accuracy and reliability.

Key Methodologies and Principles

Core Principles of SELEX and HT-SELEX

SELEX operates on the principle of in vitro selection, where a purified TF is used to isolate high-affinity binding sites through successive rounds of selection and amplification from a vast pool of random oligonucleotide sequences [14]. The power of this method lies in its ability to isolate a small set of specific binding sites from a very large pool of random sequences, typically ranging from thousands to millions of possibilities [14]. HT-SELEX builds upon this foundation by incorporating high-throughput sequencing capabilities, enabling the processing of protein binding measurements for thousands to millions of DNA sequences and providing massive datasets that comprehensively comprise TF binding preferences [10]. This technological advancement has been crucial for addressing the limitations of traditional SELEX, which was often constrained by the limited number of sequences that could be practically analyzed.

Comparative Analysis of SELEX Methodologies

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of different SELEX approaches, highlighting the advantages of HT-SELEX for profiling novel transcription factors.

Table 1: Comparison of SELEX Methodologies for Transcription Factor Profiling

| Method | Throughput | Key Features | Data Output | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional SELEX | Low | Gel mobility shift for complex separation; radio-labeled DNA [14] | 20-100 sequences | Initial binding site identification; qualitative specificity assessment |

| Affinity Chromatography-SELEX | Medium | GST-tagged protein purification; glutathione Sepharose for complex isolation [14] | 100-1,000 sequences | Rapid screening; quantitative model refinement with QuMFRA [14] |

| HT-SELEX | High | Illumina sequencing; multiple selection rounds; robust bioinformatic pipelines [10] [15] | 10,000+ sequences [16] | Comprehensive specificity determination; genome-wide binding site prediction; quantitative modeling |

Experimental Protocol: HT-SELEX for Novel Transcription Factors

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive HT-SELEX workflow for profiling transcription factor binding specificities:

Detailed Procedural Steps

Random DNA Library Design and Preparation

- Library Design: Construct a double-stranded DNA oligonucleotide pool containing a central randomized region (typically 20-40 bp) flanked by fixed sequences for PCR amplification. For a 20-nucleotide random core, the library complexity is 4²Ⱐ(approximately 1×10¹² unique sequences), ensuring comprehensive coverage of potential binding sites [10].

- Library Synthesis: Generate double-stranded DNA molecules by PCR amplification using high-fidelity DNA polymerase. Purify the products using agarose gel electrophoresis and quantify with fluorescence-based methods such as PicoGreen dsDNA quantitation [14].

Recombinant Transcription Factor Production

- Protein Expression: Clone the DNA-binding domain (DBD) of the novel TF into an appropriate expression vector (e.g., pGEX-4T-1 for GST-tagged fusion proteins). Transform into E. coli expression strains such as BL21 [14].

- Protein Purification: Induce expression with IPTG and purify the recombinant TF using affinity chromatography (e.g., glutathione Sepharose for GST-tagged proteins). Dialyze into appropriate storage buffer, concentrate, and quantify using protein assay kits [14]. Verify purity by SDS-PAGE with silver staining.

Selection Rounds (4 Rounds Recommended)

- Binding Reaction: Incubate the DNA library (∼10â»â¸ M) with purified TF (∼10â»â¸ M) in reaction buffer [30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 3 mM DTT, 20 µM ZnSOâ‚„, 25 µg/ml salmon sperm DNA] for 1 hour at room temperature [14].

- Complex Separation: For affinity chromatography SELEX, add glutathione Sepharose slurry to capture GST-tagged TF-DNA complexes. Wash extensively with reaction buffer to remove non-specifically bound DNA [14].

- Elution and Amplification: Elute bound DNA with elution buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 0.25 M KCl, 10 mM glutathione]. Amplify eluted DNA by PCR using flanking primers. Purify PCR products for subsequent selection rounds [14].

- Round Progression: Typically perform 3-4 rounds of selection, using DNA from the previous round's elution as input for the next round. The increasing stringency of selection enriches for high-affinity binding sites [10].

Sequencing and Data Processing

- Library Preparation: After the final selection round, prepare sequencing libraries from the amplified DNA. For HT-SELEX, this typically involves adapter ligation and PCR amplification compatible with Illumina sequencing platforms [15].

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Sequence the enriched library to obtain millions of reads, providing comprehensive coverage of the selected sequences. Data from the initial non-selected pool should also be sequenced to serve as a background control [10].

Data Analysis and Computational Modeling

Bioinformatic Processing Pipeline

The analysis of HT-SELEX data involves multiple computational steps to transform raw sequencing reads into quantitative models of TF binding specificity. The following diagram illustrates this analytical workflow:

Quantitative Models for Binding Specificity

Position Weight Matrix (PWM) Modeling

The Position Weight Matrix is the most commonly used model to represent DNA-binding preferences of TFs. PWM is a matrix derived from position frequency matrices, with a probability score for each nucleotide at each position. These probabilities can be added to estimate the overall binding affinity of DNA elements [10]. Major databases including JASPAR, TRANSFAC, and CIS-BP collect sequencing data and use PWM-based methods to generate and store binding motif patterns [10]. However, PWM models assume nucleotide positions are independent and may not capture more complex binding specificities.

Advanced Modeling with DCA-Scapes

For more comprehensive modeling, the global pairwise DCA-Scapes model captures the sequence specificity requirements of TF-DNA interactions from HT-SELEX data [10]. This approach involves:

- Parameter Calculation: The model infers the joint probability distribution of DNA sequences using pairwise couplings and local fields parameters, measured as an average of the four-nucleotide gauged state [10].

- Hamiltonian Scores: These parameters are collectively interpreted as a fitness function score (Hamiltonian score), which quantitatively predicts the likelihood of a DNA sequence being a target for the TF. A more negative Hamiltonian score indicates a greater likelihood of favorable TF recognition [10].

- Null Model Construction: To estimate statistical significance, a null model is constructed by calculating Hamiltonian scores for 1 million random 20-mer DNA sequences with similar nucleotide distribution to the human genome [10].

Performance Validation with Genomic Data

To test the accuracy of computational models in predicting in vivo binding sites, ChIP-seq data from the ENCODE project can be used for validation [10]. The performance evaluation involves:

- Peak Sequence Analysis: Extract sequences from the top 500 peaks in each ChIP-seq experiment and compare with control sequences from upstream and downstream regions [10].

- ROC Curve Analysis: Calculate Hamiltonian scores for both peak and control regions using a sliding window approach. Use the three most negative Hamiltonian scores to represent TF recognition specificity and generate receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to evaluate prediction performance as the area under the ROC curve (AUC) [10].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for SELEX-Based TF Binding Site Prediction

| Analysis Method | Data Input | Key Output | Validation Approach | Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position Weight Matrix (PWM) | Enriched sequences from final SELEX round [10] | Nucleotide probability matrix | Prediction of ChIP-seq peaks [10] | Limited accuracy for weak preferences [10] |

| DCA-Scapes Model | HT-SELEX reads from round 4 with initial pool as background [10] | Hamiltonian binding scores | ROC analysis against ChIP-seq data [10] | High AUC (accurate genomic binding prediction) [10] |

| Quantitative Model with QuMFRA | Subset of SELEX sequences with measured affinities [14] | Relative binding constants | Independent dataset binding affinity prediction [14] | Significantly improved prediction performance [14] |

Implementation Guide

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The successful implementation of SELEX for novel transcription factors requires carefully selected reagents and materials. The following table details the essential components and their functions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SELEX Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Library | Random oligonucleotide pool with fixed flanking sequences [14] | Source of potential binding sites; typically 20-40 bp random core | Ensure high complexity (>10¹² variants); HPLC purification |

| Expression Vector | pGEX-4T-1 (GST-tag) [14] | Recombinant TF production with affinity tag | Enables glutathione Sepharose purification |

| Chromatography Matrix | Glutathione Sepharose [14] | Separation of protein-DNA complexes from free DNA | Alternative to traditional gel shift methods |

| Binding Reaction Buffer | Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), NaCl, BSA, DTT, ZnSOâ‚„, carrier DNA [14] | Optimal binding conditions for TF-DNA interactions | Adjust salt concentration based on TF stability |

| Sequencing Platform | Illumina sequencers [15] | High-throughput analysis of enriched sequences | Enables processing of millions of sequences |

Practical Considerations for Novel Transcription Factors

When applying SELEX to poorly characterized transcription factors, several practical considerations enhance success:

- Protein Purity and Integrity: Ensure recombinant TF domains are properly folded and functional. Use structural bioinformatics to identify appropriate domain boundaries for cloning.

- Selection Stringency: Adjust binding and wash conditions across selection rounds to balance between signal-to-noise ratio and recovery of diverse binding specificities.

- Controls: Include positive control TFs with known specificities when establishing the protocol to verify system performance.

- Bioinformatic Resources: Utilize specialized databases such as HTPSELEX, which provides access to primary and derived data from high-throughput SELEX experiments [16].

SELEX and HT-SELEX provide powerful, unbiased methods for determining the binding specificities of poorly studied and novel transcription factors. By combining robust in vitro selection with advanced computational modeling, researchers can generate high-resolution TF recognition landscapes, predict genomic binding sites, and uncover tissue-specific regulatory mechanisms. The continuous development of both experimental and bioinformatic methodologies ensures that SELEX remains an indispensable tool in the functional annotation of transcription factors and the reconstruction of gene regulatory networks.

Advanced SELEX Methodologies and Applications in Biomedical Research

Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) is a powerful in vitro selection process used to identify aptamers—short, single-stranded DNA or RNA sequences—that bind to specific target molecules with high affinity and specificity [17] [18]. Since its development in the early 1990s, SELEX has revolutionized the field of molecular recognition by providing an alternative to antibodies with several distinct advantages, including easier synthetic production, enhanced stability, lower immunogenicity, and the ability to select under non-physiological conditions [18] [19]. The traditional SELEX process involves iterative rounds of selection where a random oligonucleotide library is incubated with a target, bound sequences are separated from unbound ones, and the selected sequences are amplified by PCR to generate an enriched library for subsequent rounds [18] [20]. This process continues until a population of high-affinity binders is obtained, typically requiring 8-15 rounds over several weeks or months [17] [19].

Despite its proven utility, conventional SELEX faces significant challenges, including being time-consuming, labor-intensive, and having a relatively low success rate [20]. In response to these limitations, several innovative SELEX variants have been developed that leverage advanced technologies to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of aptamer selection. Capillary Electrophoresis SELEX (CE-SELEX) utilizes the high resolving power of capillary electrophoresis to separate target-bound sequences based on their mobility shift, dramatically reducing selection time [17] [21]. Microfluidic SELEX employs miniaturized devices to automate the selection process, significantly reducing reagent consumption and enabling precise fluid control [22] [23] [20]. Cell-SELEX uses whole living cells as targets, allowing for the identification of aptamers that recognize proteins in their native conformation and cellular context [24] [25]. These advanced SELEX methodologies have transformed aptamer development, making it possible to isolate high-affinity aptamers in dramatically shorter timeframes—from weeks to days or even hours—while also expanding the range of accessible targets [17] [22] [23].

Capillary Electrophoresis SELEX (CE-SELEX)

Principle and Advantages

CE-SELEX represents a significant advancement in aptamer selection technology by leveraging the exceptional separation capabilities of capillary electrophoresis. In this method, the target molecule is incubated with a random sequence nucleic acid library, and the mixture is injected into a capillary for separation using free zone capillary electrophoresis [17]. The fundamental principle relies on the mobility shift that occurs when oligonucleotides bind to their targets; non-binding oligonucleotides migrate through the capillary with consistent mobility, while target-binding sequences undergo a complexation that alters their size and charge, causing them to migrate as a separate fraction [17] [21]. This distinct fraction of binding sequences is then collected at the capillary outlet for amplification and further enrichment rounds.

The CE-SELEX approach offers numerous advantages over conventional selection methods. Perhaps most significantly, it can isolate high-affinity aptamers in fewer rounds (typically 2-4 rounds) and without tedious negative selection compared to conventional SELEX methods, shortening a several-week process down to as little as a few days [17]. The selection occurs in free solution, eliminating the need for filtration or solid-phase attachment of the target, which increases the number and types of viable targets—including targets smaller than the aptamer itself [17]. CE-SELEX also provides exceptional flexibility to manipulate selection stringency by varying target concentration, separation parameters, and collection window timing [17]. Furthermore, this method is compatible with many non-natural nucleic acid libraries and modifications that cause issues for other SELEX techniques and can work with limited samples, having been successfully used with target concentrations as low as 1 pM [17].

Protocol for CE-SELEX

The CE-SELEX protocol involves several key steps and specialized reagents. Begin by preparing a 5'-FAM labeled ssDNA library consisting of a random region (typically 40 bases) flanked by 20-base constant primer regions, diluted to 400 μM in nuclease-free water [17]. Prepare separation buffer (5x TGK buffer: 125 mM Tris-HCl, 960 mM glycine, 25 mM KH₂PO₄, pH 8.3) and sample buffer that matches anticipated application conditions [17].

Procedure:

- Incubation: Mix the ssDNA library with the target molecule in sample buffer and incubate to allow binding interactions.

- Capillary Electrophoresis: Inject several nanoliters of the incubation mixture onto a bare fused silica capillary (50 μm i.d.) using an automated P/ACE MDQ Plus CE instrument. Apply separation voltage in 1x TGK buffer.

- Collection: Monitor separation by laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) detection. Collect the shifted fraction corresponding to target-ssDNA complexes at the capillary outlet.

- Amplification: PCR amplify the collected sequences using FAM-labeled forward primer and biotin-labeled reverse primer.

- Purification: Purify the amplified product using streptavidin agarose resin to generate single-stranded DNA for subsequent selection rounds.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 1-5 for 2-4 rounds until no further improvement in affinity is observed.

Critical Steps:

- Maintain sample buffer with at least 5 mM K⺠to allow formation of DNA G-quadruplex motifs if needed for binding.

- Precisely optimize collection window timing to balance specificity and recovery.

- Monitor enrichment after each round by analyzing the increasing proportion of shifted complex in capillary electrophoresis.

Applications and Performance

CE-SELEX has demonstrated exceptional performance in generating high-affinity aptamers for various targets. The method has been successfully used to select DNA aptamers with affinities in the nanomolar to picomolar range [17] [21]. For example, researchers have selected aptamers targeting neuropeptide Y using CE-SELEX, achieving high-affinity binders in significantly fewer rounds than conventional methods [17]. The technique has also been adapted in various forms, including Non-SELEX approaches that eliminate PCR amplification between rounds, further accelerating the selection process [21]. Single-step CE-SELEX represents another innovation that integrates mixing, reaction, separation, and detection into a single online step, dramatically shortening experimental time and reducing resource consumption while enhancing sample utilization from 5% to 100% [21].

Table 1: Key Advantages of CE-SELEX Over Conventional SELEX

| Parameter | CE-SELEX | Conventional SELEX |

|---|---|---|

| Selection Rounds | 2-4 rounds [17] | 8-15 rounds [17] |

| Time Required | Few days [17] | Several weeks [17] |

| Selection Environment | Free solution [17] | Solid-phase immobilization [17] |

| Target Limitations | Compatible with targets smaller than aptamer [17] | Size limitations for immobilization |

| Stringency Control | Precise via separation parameters [17] | Limited manipulation options |

| Sequence Motifs | Rare, allowing more optimization flexibility [17] | More common |

Microfluidic SELEX

Principle and Advantages

Microfluidic SELEX leverages the principles of miniaturization and automation to revolutionize the aptamer selection process. This approach utilizes integrated microfluidic chips equipped with micropumps, microvalves, micromixers, and micro nucleic acid amplification modules to perform the entire SELEX process in an automated fashion [23] [20]. The fundamental principle involves the precise manipulation of minute fluid volumes within microchannels and chambers to facilitate the binding, separation, washing, and amplification steps of SELEX in a continuous, automated system [22] [20]. These systems can implement various force fields—including hydrodynamic, electric, magnetic, and acoustic—to enhance the efficiency of aptamer selection [20].

The advantages of microfluidic SELEX are substantial. The most prominent benefit is the dramatic reduction in selection time; where conventional SELEX requires weeks, microfluidic systems can complete the entire process in hours [22] [23]. One reported system completed 7 rounds of SELEX in only 14 hours, while another achieved selection of high-affinity DNA aptamers against immunoglobulin E (IgE) in just 4 rounds requiring approximately 10 hours [22] [23]. Microfluidic systems also offer significantly reduced consumption of samples and reagents, making them cost-effective for working with precious or expensive targets [20]. The automated nature of these systems minimizes manual handling, improving reproducibility and reducing operator-induced variability [22]. Additionally, microfluidic platforms enable precise control over shear forces during washing steps, which is crucial for selecting high-affinity aptamers under physiologically relevant conditions [23]. This precise control allows researchers to optimize selection stringency by adjusting flow rates and shear forces to mimic in vivo conditions, potentially leading to aptamers with better performance in practical applications [23] [20].

Protocol for Microfluidic SELEX

Implementing microfluidic SELEX requires specialized equipment and careful optimization. Begin with an integrated microfluidic device featuring selection and amplification chambers with integrated thin-film resistive heaters and temperature sensors, interconnected by reagent transport channels [22]. The device should include mechanisms for both electrokinetic and pressure-driven transport of oligonucleotides [22].

Procedure:

- Device Preparation: Functionalize microbeads with the target molecule and immobilize them in the selection chamber using a microweir structure [22].

- Negative Selection (Optional): Introduce the random ssDNA library to non-target functionalized beads to remove non-specific binders.

- Positive Selection: Introduce the pre-cleared library to the target-functionalized beads in the selection chamber and allow binding.

- Washing: Apply precisely controlled shear forces using serpentine-shaped micropumps to remove weakly bound sequences [23].

- Elution: Thermally release bound oligonucleotides from the target using integrated heaters.

- Transfer: Electrokinetically migrate eluted oligonucleotides through a gel-filled channel to the amplification chamber [22].

- Amplification: Capture oligonucleotides on reverse primer-functionalized magnetic beads, introduce PCR reagents, and perform on-chip PCR amplification.

- ssDNA Generation: Thermally denature amplified products and transfer the ssDNA via pressure-driven flow back to the selection chamber.

- Iteration: Automatically repeat steps 3-8 for multiple rounds (typically 4-7 rounds).

Critical Steps:

- Precisely characterize and optimize micropump volumes and mixing indices for consistent operation.

- Implement a custom shear force control strategy during washing steps to enhance affinity of selected candidates [23].

- Incorporate negative and competitive selection rounds as needed to enhance specificity [23].

Applications and Performance

Microfluidic SELEX has demonstrated impressive performance in selecting high-affinity aptamers for various targets. In one notable application, researchers used an integrated microfluidic system equipped with a shear force control device to select aptamers targeting folate receptor alpha (FRα), a key biomarker for ovarian cancer diagnosis [23]. The system completed seven SELEX rounds within 14 hours, incorporating five positive selections, one negative selection, and one competitive selection round to enhance specificity [23]. The resulting top candidate aptamer displayed a dissociation constant (Kd) as low as 23 nM, which is superior to aptamers obtained through conventional SELEX [23]. The selected aptamer was successfully applied in a detection assay to quantify FRα in spiked serum samples (1-15 μg/L), demonstrating its potential for early ovarian cancer diagnosis [23].

Another study demonstrated the selection of DNA aptamers against the protein IgE with high affinity (Kd = 12 nM) in a rapid manner (4 rounds in approximately 10 hours) using a microfluidic approach that employed bead-based biochemical reactions and hybrid electrokinetic and pressure-driven transport [22]. These systems have also been adapted for cell-SELEX applications, further expanding their utility in identifying aptamers against complex cellular targets [20].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Microfluidic SELEX Platforms

| Parameter | Reported Performance | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Selection Time | 4 rounds in ~10 hours [22]; 7 rounds in 14 hours [23] | Dramatic reduction from weeks to hours |

| Affinity (Kd) | 12 nM for IgE [22]; 23 nM for FRα [23] | High-affinity binders comparable or superior to conventional SELEX |

| Automation Level | Full integration of binding, washing, amplification, and ssDNA generation [22] [20] | Minimal manual intervention, improved reproducibility |

| Reagent Consumption | Nanoliters to microliters per round [20] | Significant cost savings, enables work with precious targets |

| Shear Force Control | Custom serpentine micropumps for optimized washing [23] | More physiologically relevant selection conditions |

Cell-SELEX

Principle and Advantages

Cell-SELEX represents a paradigm shift in aptamer selection by using whole living cells as targets rather than purified molecules. This approach involves incubating the random oligonucleotide library with intact cells, allowing aptamers to bind to native cell surface structures in their physiological conformation and environment [24] [25]. The fundamental principle leverages the complex molecular landscape of the cell surface, enabling the identification of aptamers that recognize naturally folded proteins, protein complexes, and other cell surface components without prior knowledge of specific molecular targets [24]. The process typically involves iterative rounds of selection against target cells, counter-selection against control cells (to remove binders to common surface molecules), and amplification of bound sequences.

The advantages of Cell-SELEX are substantial and complementary to other SELEX variants. Most importantly, it allows for the discovery of aptamers against unknown cell surface biomarkers, making it particularly valuable for cancer research where specific surface profiles may not be fully characterized [24] [25]. The selected aptamers recognize their targets in native conformations with appropriate post-translational modifications, increasing the likelihood that they will function effectively in biological applications [24] [25]. Cell-SELEX can also reveal novel insights into cell surface biology; for example, one study demonstrated that mutant K-Ras expression dynamically alters cell surface composition and can cause abnormal translocation of a mitochondrial matrix protein to the cell surface without detectable changes in mRNA or protein levels [24]. This capability makes Cell-SELEX a powerful tool for investigating cell surface remodeling under different physiological and pathological conditions. Furthermore, aptamers selected through Cell-SELEX often show excellent specificity for their target cell type, able to distinguish between closely related cells based on subtle surface differences [24] [25].

Protocol for Cell-SELEX

Implementing Cell-SELEX requires careful cell culture practices and specific modifications to incorporate enhanced functionality. Begin by preparing a single-stranded DNA library with a central random region (typically 30-60 nucleotides) flanked by constant primer regions, enzymatically synthesized to incorporate modified bases such as tryptamino-dU (trp-dU) instead of dT to enhance DNA aptamer functionality by introducing artificial hydrophobic residues [24].

Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Maintain target cells (e.g., cancer cells) and control cells (e.g., non-malignant counterparts) under standard conditions.

- Negative Selection: Incubate the ssDNA library with control cells to remove sequences binding to common surface molecules. Collect unbound sequences.

- Positive Selection: Incubate the pre-cleared library with target cells. Allow binding under appropriate conditions.

- Washing: Gently wash cells to remove weakly bound or non-specifically bound sequences.

- Elution: Recover bound sequences by heating cell-aptamer complexes or using other elution methods.

- Amplification: Amplify eluted sequences by PCR or RT-PCR (for RNA aptamers).

- ssDNA Generation: Generate single-stranded DNA from amplified products for subsequent selection rounds.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-7 for multiple rounds (typically 5-15 rounds), monitoring enrichment of cell-specific binders.