Gene-Centered Frameworks for Prokaryotic Regulon Analysis: From Foundational Concepts to Biomedical Applications

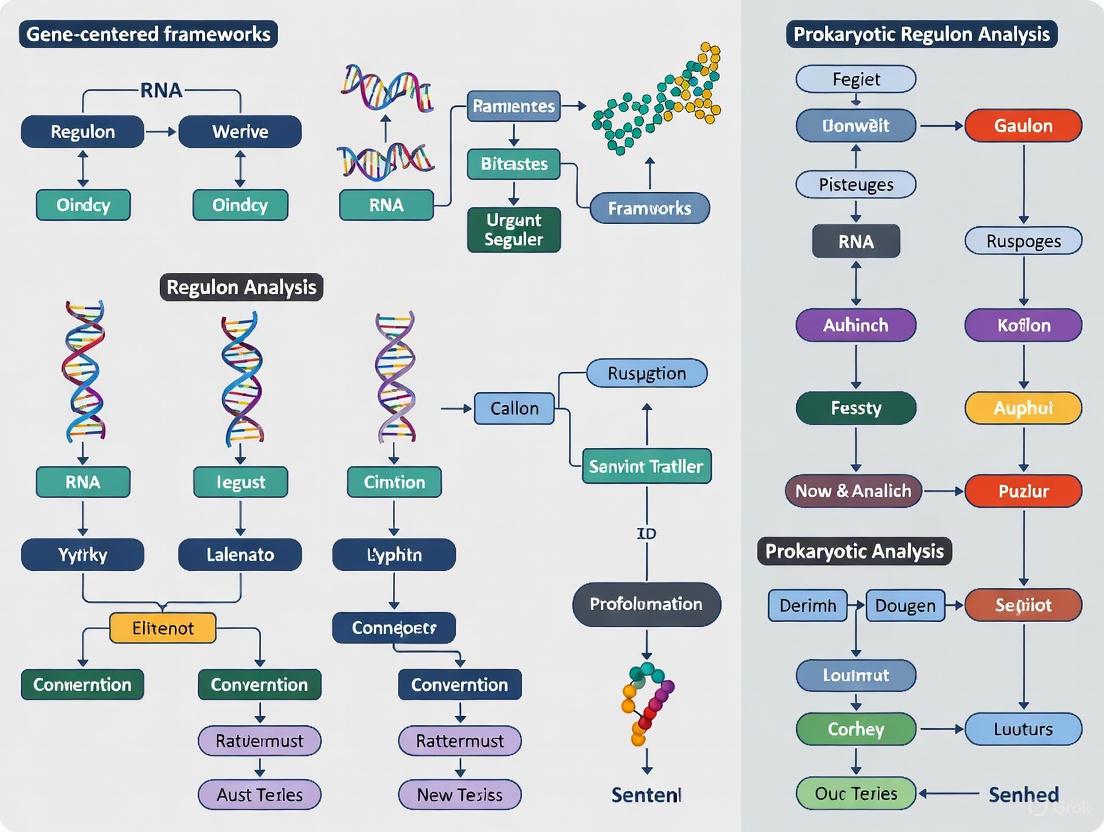

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the paradigm shift from operon-centric to gene-centered frameworks in prokaryotic regulon analysis.

Gene-Centered Frameworks for Prokaryotic Regulon Analysis: From Foundational Concepts to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the paradigm shift from operon-centric to gene-centered frameworks in prokaryotic regulon analysis. It explores the foundational principles of bacterial transcriptional regulation, detailing advanced computational methodologies like the CGB platform that employ Bayesian probabilistic models for regulon reconstruction. The content addresses common challenges in motif discovery and network inference, offering optimization strategies for improved accuracy. By examining validation techniques and comparative genomic approaches, it highlights the power of these frameworks to elucidate complex regulatory networks. Finally, the article discusses the translational potential of this knowledge in drug discovery and therapeutic development, providing a vital resource for researchers and bioinformatics professionals aiming to decode bacterial genetic circuitry.

Decoding Prokaryotic Gene Regulation: From Sigma Factors to Complex Networks

In prokaryotes, the fundamental machinery responsible for transcription consists of the core RNA polymerase (RNAP) and its associated sigma (σ) factors. This partnership forms the RNAP holoenzyme, which is indispensable for the initiation of gene transcription by recognizing and binding to specific promoter sequences upstream of genes [1] [2]. The core RNAP is a multi-subunit enzyme capable of RNA synthesis but lacks promoter specificity. This specificity is conferred by the sigma factor, which directs the holoenzyme to specific promoters, thereby playing a pivotal role in global gene regulation [3] [4]. Understanding the architecture and function of this machinery is central to gene-centered frameworks for prokaryotic regulon analysis, as it allows researchers to decipher the complex hierarchical networks that govern bacterial gene expression in response to physiological and environmental cues [5] [6]. This application note provides a detailed overview of the core components, their regulatory mechanisms, and practical experimental protocols for studying their function.

Core Components of the Transcriptional Machinery

Core RNA Polymerase

The core RNA polymerase is a multi-subunit molecular machine that is catalytically competent for RNA synthesis but unable to initiate transcription at specific promoter sites on its own [7] [3]. The composition and primary functions of its subunits are detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Subunit Composition of Core Bacterial RNA Polymerase

| Subunit | Gene (in E. coli) | Number in Complex | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| α | rpoA |

2 | Serves as a scaffold for holoenzyme assembly; interacts with upstream promoter elements and transcriptional activators. |

| β | rpoB |

1 | Forms the catalytic center for RNA synthesis; binds nucleoside triphosphate substrates. |

| β' | rpoC |

1 | Binds template DNA; interacts with sigma factors and other regulatory proteins. |

| ω | rpoZ |

1 | Involved in core enzyme assembly and stability; may play a role in regulation. |

Sigma Factors

Sigma factors are dissociable subunits that bind the core RNAP to form the holoenzyme, thereby conferring promoter specificity [1]. The sigma factor is responsible for recognizing the -10 and -35 promoter elements, facilitating open complex formation, and stimulating the initial steps of RNA synthesis [8] [2]. Most sigma factors belong to the σ70-family, which can be classified into four groups based on sequence conservation and domain architecture [1] [9].

Table 2: Classification and Properties of Major Sigma Factors in Escherichia coli

| Sigma Factor | Group | Gene | Primary Physiological Role | Key Recognized Promoter Elements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ70 | Group 1 (Primary) | rpoD |

Housekeeping transcription during exponential growth [1]. | -10 (TATAAT) and -35 (TTGACA) [8] |

| σS (RpoS) | Group 2 | rpoS |

Starvation/stationary phase and general stress response [1] [4]. | Similar to σ70, with variations [8] |

| σH (RpoH) | Group 3 | rpoH |

Cytoplasmic heat shock response [1] [4]. | -10 and -35, distinct from σ70 |

| σ28 (RpoF/FliA) | Group 3 | fliA |

Flagellar synthesis and chemotaxis [1]. | -10 and -35, distinct from σ70 |

| σ54 (RpoN) | σ54 Family | rpoN |

Nitrogen limitation and other specific functions [1]. | -12 and -24, requires activator ATP hydrolysis |

| σE (RpoE) | Group 4 (ECF) | rpoE |

Response to extracytoplasmic stress, such as misfolded proteins in the periplasm [3] [1]. | -10 and -35, recognized by σ2 and σ4 domains [9] |

| σFecI | Group 4 (ECF) | fecI |

Ferric citrate transport [1]. | -10 and -35, recognized by σ2 and σ4 domains |

ECF: Extracytoplasmic Function

Structural Architecture and Mechanism of Transcription Initiation

Domain Organization of σ70-Family Factors

The σ70-family factors share a modular architecture, though not all domains are present in every group [1] [9]:

- Domain 1.1 (σ1.1): Found only in primary sigma factors (Group 1); acts as a molecular mimic of DNA, preventing free sigma from binding DNA and ensuring it only binds promoters when complexed with the core RNAP [1].

- Domain 2 (σ2): Contains highly conserved regions that recognize the -10 promoter element (

TATAAT) and are critical for melting the DNA duplex to form the transcription bubble [8]. - Domain 3 (σ3): Contributes to the recognition of the "extended -10" element in some promoters and serves as a linker to domain 4 [9].

- Domain 4 (σ4): Contains a helix-turn-helix motif that recognizes the -35 promoter element (

TTGACA) and interacts with the β-flap domain of the core RNAP [3] [8].

Group 2 factors lack domain 1.1, while Group 4 (ECF) sigma factors typically contain only the σ2 and σ4 domains [1] [9]. The following diagram illustrates the process of transcription initiation and the key regulatory checkpoints.

Diagram 1: The transcription initiation pathway and the sigma cycle, illustrating the key steps from holoenzyme assembly to promoter escape.

Regulatory Mechanisms of Sigma Factor Activity

The activity of sigma factors is tightly controlled at multiple levels to ensure appropriate gene expression in response to cellular needs. Key regulatory mechanisms include:

- Anti-Sigma Factors: Proteins that bind directly to their cognate sigma factor and inhibit its activity by sterically occluding its RNAP- or DNA-binding domains [3]. For example, RseA binds and inhibits σE in E. coli, while FlgM inhibits σ28 [3].

- Anti-Anti-Sigma Factors: Proteins that bind to and inactivate anti-sigma factors, thereby restoring sigma factor activity. SpoIIAA is an anti-anti-sigma factor that regulates σF activity during sporulation in Bacillus species [3].

- Sigma Factor Competition: Since the number of core RNAP molecules is limited, overexpression of one sigma factor can titrate the core enzyme and reduce the transcription of genes dependent on other sigma factors [1].

- σ-Regulator Proteins: An emerging class of regulators, such as Crl in E. coli and RbpA in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, that bind to sigma or the RNAP holoenzyme prior to promoter binding and remodel the sigma subunit's conformation to modify its activity [8].

The following diagram summarizes the complex regulatory interactions that control sigma factor activity.

Diagram 2: Key regulatory mechanisms controlling bacterial sigma factor activity, including inhibition, sequestration, and activation.

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing Sigma Factor-Promoter Interactions

Protocol: Computation-Guided Redesign of Sigma Factor Specificity

This protocol, adapted from a recent study, outlines a workflow for engineering the promoter specificity of a sigma factor using computational design and high-throughput screening [7].

1. Library Design via Rosetta Modeling

- Input Structure: Use a crystal structure of the target sigma factor in complex with its canonical promoter DNA (e.g., PDB: 4YLN for E. coli σ70) [7].

- Combinatorial Mutagenesis Scan: Perform computational scans of key DNA-recognition residues (e.g., positions R584, E585, R586, R588, and Q589 in σ70). Generate all possible single, double, triple, and quadruple mutants [7].

- Energy Scoring: Calculate the stability of each mutant's protein-DNA interface with the target orthogonal promoter sequence using Rosetta. The protein-DNA interface score is calculated as the average across 10 optimized structures [7].

- Variant Selection: Select the top 1,000 sigma factor variants with the highest affinity (lowest interface energy score) for each target promoter for experimental validation [7].

2. Library Preparation and Cloning

- Oligo Synthesis: Order a pooled single-stranded DNA oligo library (e.g., 110-base pair fragments) encoding the designed sigma variants with unique priming regions and BsaI recognition sites [7].

- Backbone Preparation: Amplify a plasmid backbone (e.g., SC101LacIWTsigma) containing a wild-type sigma gene under an inducible promoter. Digest the amplified backbone with DpnI and BsaI-HF-v2 to create sticky ends and treat with Antarctic Phosphatase to prevent re-ligation [7].

- Golden Gate Assembly: Assemble the library by combining the digested backbone with the amplified sigma variant library in a Golden Gate reaction using BsaI. Dialyze the assembled reaction before transformation [7].

3. High-Throughput Screening and Selection

- Transformation: Transform the assembled library into electrocompetent E. coli (e.g., DH10β) via electroporation. Plate dilutions to measure transformation efficiency and grow the library overnight for storage [7].

- Induction and Sorting: Induce sigma factor expression (e.g., with IPTG) and measure the output, typically a fluorescent reporter gene under the control of the target orthogonal promoter. Use Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to isolate cell populations with high fluorescence, indicating successful promoter recognition by the redesigned sigma factor [7].

- Deep Sequencing: Sequence the sorted populations to identify enriched sigma variant sequences and determine the sequence determinants of the new promoter specificity [7].

Protocol: Analyzing Sigma Factor Activity with Fluorescent Reporters

This protocol describes a method to quantify the activity of sigma factors on their target promoters in vivo.

1. Strain and Plasmid Construction

- Clone the sigma factor gene into an inducible expression plasmid (e.g., pLacO).

- Clone the target promoter upstream of a promoterless fluorescent reporter gene (e.g., GFP) on a reporter plasmid.

- Co-transform both plasmids into an appropriate bacterial strain. A control strain containing only the reporter plasmid should be included.

2. Induction and Fluorescence Measurement

- Inoculate colonies into a 96-well plate containing LB medium with appropriate antibiotics.

- Grow cultures at 37°C with shaking until the OD600 reaches approximately 0.6.

- Back-dilute cultures into fresh medium in technical replicates. Induce sigma factor expression when OD600 reaches ~0.3 (e.g., with a final concentration of 1 mM IPTG) [7].

- Continue growth for a set period post-induction (e.g., 3 hours).

3. Data Acquisition and Analysis

- Measure the OD600 and fluorescence (e.g., GFP excitation: 488 nm, emission: 510 nm) for each culture using a plate reader.

- Calculate the specific promoter activity by normalizing the fluorescence units to the OD600 of the culture.

- Compare the activity of the redesigned sigma factor to that of the wild-type sigma factor on its canonical active promoter to determine relative activity (e.g., reported activities range from 17% to 77% of native) [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Studying Bacterial Transcription Machinery

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Core RNAP (Purified) | Catalytic core of transcription; can be reconstituted with sigma factors for in vitro studies. | Used in gel shift assays, in vitro transcription, and structural studies (e.g., cryo-EM) [9]. |

| Sigma Factor Expression Plasmids | Plasmids for inducible expression of wild-type or mutant sigma factors. | Essential for in vivo functional complementation and promoter activity assays [7]. |

| Promoter-Reporter Plasmids | Plasmids where a promoter of interest drives a reporter gene (e.g., GFP, mCherry). | Quantifying promoter strength and sigma factor specificity in vivo [7]. |

| Oligo Library Pools | Pooled single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides encoding designed protein variants. | For generating large, diverse variant libraries for directed evolution and screening [7]. |

| Golden Gate Assembly System | A versatile, type IIS restriction enzyme-based DNA assembly method. | Efficient, scarless cloning of variant libraries into expression vectors [7]. |

| Rosetta Modeling Software | Macromolecular modeling software for predicting protein-DNA interactions and designing mutants. | Computational design of sigma factor variants with altered promoter specificity [7]. |

| Anti-Sigma Factor Antibodies | Antibodies specific to different sigma factors or their epitope tags. | Detecting sigma factor expression levels and localization via Western blot or ChIP. |

| Cryo-EM Infrastructure | Equipment and software for single-particle cryo-electron microscopy. | Determining high-resolution structures of RNAP holoenzymes in complex with promoters [9]. |

| SARS-CoV-2-IN-60 | SARS-CoV-2-IN-60, MF:C13H7Cl2F3N2O, MW:335.10 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Antibacterial agent 73 | Antibacterial agent 73, MF:C15H17FN2O, MW:260.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application in Regulon Analysis and Concluding Remarks

The architecture of the bacterial transcriptional machinery is a cornerstone for gene-centered regulon analysis. By understanding the specific promoter recognition patterns of different sigma factors and the global regulators that control their availability, researchers can map transcriptional regulatory networks on a genome-wide scale [5]. Techniques such as computation-guided engineering of sigma factors enable the creation of orthogonal genetic systems, allowing for the selective insulation of synthetic circuits from host regulation and the potential for global rewiring of transcriptional programs [7]. Furthermore, advanced methods like single-cell RNA-sequencing are revealing how transcription-replication interactions (TRIPs) and the genomic context of a gene contribute to expression heterogeneity, providing a more nuanced, quantitative framework for modeling bacterial gene regulation [6] [10]. The continued elucidation of the structure, function, and regulation of core RNAP and sigma factors remains fundamental to both basic bacterial physiology and applied synthetic biology.

In prokaryotic systems, Transcription Factors (TFs) function as critical regulatory hubs, orchestrating gene expression in response to environmental and intracellular signals. The organizational principle of transcriptional regulatory networks (TRNs) reveals a structure where a small number of global regulators (hubs) control a disproportionately large number of target genes [11]. In the model organism Escherichia coli, the TRN consists of 146 specific TFs regulating 1,175 target genes through 2,489 documented interactions [11]. These TFs can be systematically classified by their regulatory mode—as activators, repressors, or dual regulators—and by their signal-sensing mechanisms, which include one-component systems responding to internal or external signals, TFs from two-component systems, and chromosomal structure-modifying TFs [11]. Understanding the properties and interactions of these different TF classes is fundamental to constructing a gene-centered framework for prokaryotic regulon analysis.

The functional characterization of TFs provides critical insights into their regulatory logic. In E. coli, the distribution of regulatory modes among its 146 TFs is quantified as follows [11]:

Table 1: Classification of E. coli Transcription Factors by Regulatory Mode

| Regulatory Mode | Count | Percentage | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activator | 58 | 39.7% | Increases transcription of target genes |

| Repressor | 47 | 32.2% | Decreases transcription of target genes |

| Dual Regulator | 41 | 28.1% | Can act as both activator and repressor |

Furthermore, TFs can be categorized by their signal-sensing mechanisms, which determine how they perceive and respond to environmental and metabolic changes [11]:

Table 2: Classification of E. coli TFs by Signal-Sensing Mechanism

| Sensory Mechanism | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| One-Component Systems (Internal) | Sense internal metabolites (endogenous ligands, redox, pH) using fused sensory and DNA-binding domains | |

| One-Component Systems (External) | Sense external metabolites transported into the cell | |

| Hybrid One-Component Systems | Sense both external metabolites and their internal derivatives | |

| Two-Component Systems | Involve a sensory histidine kinase and a downstream response regulator TF | |

| Chromosomal Proteins | Modulate DNA curvature and structure to influence transcription |

The interplay between regulatory mode and sensory mechanism creates a multi-dimensional selection process that shapes the hierarchical structure of the TRN, ultimately generating circuits that allow for intricately regulated physiological state changes [11].

Protocol: Mapping a Co-Regulatory Network from Transcriptional Regulatory Data

Background and Principle

A Co-Regulatory Network (CRN) is a transformation of the TRN that explicitly represents associations between TFs that co-regulate the same target genes. Analyzing the CRN reveals higher-order organizational principles and highlights TFs that serve as integrators of multiple regulatory inputs, even if they are not hubs in the original TRN [11]. This protocol details the steps for constructing a CRN from established TRN data, using E. coli as a model.

Materials and Reagents

- Computing Environment: Computer with standard specifications capable of running R or Python.

- Software: R statistical software (v4.0.0 or higher) or Python (v3.7 or higher).

- Data Source: Curated TRN data for the organism of interest. For E. coli, this can be obtained from RegulonDB [11] [12] [13].

- R/Packages: The

igraphpackage in R (or theNetworkXlibrary in Python) for network manipulation and analysis.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Acquisition and Curation:

- Download the complete set of known TF-target gene interactions from RegulonDB (or an equivalent curated database for your organism).

- Load the data into your analytical environment. The data should be structured as a table with at least two columns: "TF" and "Target_Gene".

Construction of the Transcriptional Regulatory Network (TRN):

- Represent the TRN as a directed graph. In this graph:

- Nodes represent all TFs and their target genes.

- A directed edge is drawn from a TF node to a target gene node, representing the regulatory interaction.

- This creates the foundational TRN graph, GTRN.

- Represent the TRN as a directed graph. In this graph:

Network Transformation to Build the Co-Regulatory Network (CRN):

- From GTRN, generate a new graph, GCRN, where:

- Nodes represent only the TFs from the original TRN.

- An undirected edge is placed between two TF nodes if they jointly regulate one or more common target genes. The number of shared targets can be stored as a weight on the edge.

- This transformation reveals the "co-regulatory associations" between TFs.

- From GTRN, generate a new graph, GCRN, where:

Validation and Normalization (Optional):

- Subject the resulting CRN to a normalization procedure to confirm the validity of strong associations. In studies of E. coli, this process retained 90% of co-regulatory associations and all but one of the hub TFs [11].

Interpretation of Results

- Hub Identification: TFs with a high number of connections (degree) in the CRN are key co-regulators. In E. coli, most CRN hubs are also global regulators in the TRN (e.g., Crp). Exceptions like Hu, Rob, and RcsB may have fewer direct targets but perform distinctive integrative roles [11].

- Module Detection: Clusters of highly interconnected TFs in the CRN often represent functional modules that coordinately control specific biological processes.

Protocol: Identifying Key Regulatory Hubs via Network Centrality Analysis

Background and Principle

While predicting individual TF-gene interactions from expression data alone remains challenging, network-level topological analysis can successfully reveal biologically meaningful organizational principles and identify key regulators [12] [13]. This protocol uses gene network centrality analysis to identify potential master regulators, such as in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus, where it helped identify known global regulators (RpaA, RpaB) and previously understudied TFs (HimA, TetR, SrrB) as key nodes coordinating day-night metabolic transitions [12] [13].

Materials and Reagents

- Gene Expression Dataset: A curated, normalized gene expression matrix (e.g., RNA-Seq TPM counts) across multiple conditions or time points. The example dataset "selongEXPRESS" contained 330 samples [12] [13].

- TF List: A curated list of transcription factors for the organism, which can be compiled using databases like P2TF, ENTRAF, or prediction tools like DeepTFactor [12] [13].

- Software/Tools: R or Python environment with the following key packages/libraries:

- GENIE3: For initial network inference (available as an R package).

- igraph (R) or NetworkX (Python): For network analysis and centrality calculation.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Preprocessing and TF-Gene Network Inference:

- Perform rigorous quality control on the expression data (e.g., using FastQC, correlation analysis between replicates).

- Normalize expression values (e.g., log-TPM transformation).

- Use a network inference tool like GENIE3 on the expression matrix to predict potential regulatory links, generating a weighted adjacency matrix where edges represent the strength of putative regulatory relationships.

Network Construction and Pruning:

- Construct an unweighted or weighted directed network from the adjacency matrix. A common practice is to prune very weak edges by keeping only the top N predictions per gene or applying a global weight threshold.

Calculation of Network Centrality Metrics:

- Calculate the following centrality measures for each TF node in the network:

- Out-Degree Centrality: The number of genes a TF regulates. High out-degree indicates a global regulator/hub.

- Betweenness Centrality: Measures how often a node lies on the shortest path between other nodes. High betweenness indicates a connector or integrator between different network modules.

- Closeness Centrality: Measures how quickly a node can reach all other nodes. High closeness indicates potential for efficient propagation of regulatory influence.

- Calculate the following centrality measures for each TF node in the network:

Integration and Biological Interpretation:

- Rank TFs based on each centrality metric.

- Integrate rankings to identify TFs that consistently rank highly across multiple metrics.

- Cross-reference high-centrality TFs with functional data (e.g., gene ontology, known phenotypes, expression patterns) to hypothesize their biological roles.

Interpretation of Results

- In S. elongatus, this analysis identified distinct regulatory modules for daytime (photosynthesis, carbon/nitrogen metabolism) and nighttime (glycogen mobilization, redox metabolism) processes [12] [13].

- TFs like RpaA and RpaB were confirmed as high-centrality hubs, while HimA was identified as a putative DNA architecture regulator, and TetR and SrrB as potential nighttime metabolism coordinators [12] [13].

Protocol: Comparing Transcription Factor Binding Motifs with DiffLogo

Background and Principle

Sequence logos are the standard for visualizing sequence motifs, but perceiving differences between related motifs (e.g., for the same TF from different conditions, or for different TFs in the same family) from individual logos is challenging [14]. The DiffLogo R package provides an intuitive visualization of pair-wise differences between two motifs, highlighting position-specific variations in symbol abundance and conservation [14]. This is crucial for analyzing subtle changes in TF binding specificity.

Materials and Reagents

- Computing Environment: R statistical software (v4.0.0 or higher).

- R Packages:

DiffLogo(available from Bioconductor). - Input Data: Two position frequency matrices (PFMs) or position weight matrices (PWMs) representing the motifs to be compared. These can be obtained from motif discovery tools (e.g., MEME, ChIPMunk) or databases (e.g., JASPAR, UniProbe).

Step-by-Step Procedure

Installation and Loading:

- Install and load the DiffLogo package in R.

Data Preparation:

- Load the two motifs to be compared. Ensure they are represented as PFMs or PWMs.

- Example using two PFMs (

pfm1andpfm2):

Visualization of Motif Differences:

- Use the

diffLogofunction to generate the difference logo. - The function calculates the difference in symbol distributions at each position. The stack height represents the degree of dissimilarity (e.g., using Jensen-Shannon divergence), while the height of each symbol within the stack is proportional to its differential abundance [14].

- Use the

Interpretation of Results

- Upward Bars: Represent symbols that are more abundant in the first motif (

pfm1). - Downward Bars: Represent symbols that are more abundant in the second motif (

pfm2). - Stack Height: Indicates the magnitude of the difference at that position; taller stacks signify more divergent positions.

- This visualization helps in understanding how binding specificity might vary between TFs, or for the same TF under different conditions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Prokaryotic Regulon Analysis

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in Analysis | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curated Regulatory Database | Database | Provides gold-standard, experimentally validated TF-gene interactions for network construction and validation. | RegulonDB [11] [12] |

| TF Prediction Pipeline | Software/Database | Identifies and annotates putative transcription factors in a prokaryotic genome. | P2TF, ENTRAF, DeepTFactor [12] [13] |

| Network Inference Tool | Algorithm/Software | Predicts potential regulatory relationships from gene expression data. | GENIE3 [12] [13] |

| Network Analysis Library | Software Library | Constructs, manipulates, and analyzes network properties and centrality metrics. | igraph (R), NetworkX (Python) |

| Motif Comparison Tool | Software | Visually compares and contrasts two sequence motifs to identify differences in binding specificity. | DiffLogo R package [14] |

| Integrated Analysis Platform | Software Platform | Provides a unified environment with multiple tools for omics data analysis, including TF binding site prediction. | geneXplain platform [15] |

The concept of the regulon is foundational to prokaryotic genetics, representing a set of genes or operons regulated by a common transcription factor. This framework has evolved significantly from its original definition, expanding from the classical operon model to encompass broader, systems-level understandings of gene regulation. The original operon theory, pioneered by François Jacob and Jacques Monod, described a cluster of genes transcribed together as a single polycistronic mRNA molecule under the control of a single promoter and operator region [16] [17]. Their groundbreaking work on the lac operon in E. coli demonstrated how a single regulatory element could control the expression of multiple genes involved in lactose metabolism, revealing for the first time the fundamental principles of gene regulation at the transcriptional level [17]. This model introduced the concept of regulatory genes that encode repressor proteins capable of suppressing transcription by binding to operator sequences, effectively establishing the paradigm of negative regulation [16].

In the decades since this discovery, the operon concept has matured considerably, revealing tremendous versatility in regulatory mechanisms. Researchers discovered that bacterial genes can be regulated by activators (positive regulation), subjected to both positive and negative control simultaneously, or synergistically controlled by combinations of regulatory proteins [17]. The original model has been expanded to incorporate modern genomic and computational approaches, leading to the development of gene-centered frameworks that provide unprecedented resolution for understanding prokaryotic gene regulatory networks. These frameworks are particularly valuable for associating uncharacterized genes with cellular processes, refining metabolic models, and enabling rational genetic engineering of cellular systems [18].

Classical Operon Theory: Historical Foundations

The PaJaMo Experiment and Operon Discovery

The conceptual foundation for operon theory emerged from the seminal PaJaMo experiment (named for Pardee, Jacob, and Monod), which provided critical evidence for the existence of mobile regulatory elements [17]. This experiment demonstrated that the regulation of β-galactosidase synthesis involved a diffusable repressor molecule, suggesting a model of negative regulation where the repressor protein prevents transcription by binding to the operator DNA sequence. This work generated two fundamental concepts: messenger RNA and the operon itself [17]. The operon model formally proposed that the product of a regulator gene (the repressor) controls and coordinates a group of genes with related functions, with the repressor acting in trans and the operator functioning in cis to the operon [17].

Key Characteristics of Classical Operons

Operons represent one of the principal schemes of gene organization and regulation in prokaryotes, with approximately half of all protein-coding genes in a typical prokaryotic genome organized in multigene operons [17]. These structures typically share several defining characteristics:

- Polycistronic transcription: Genes within an operon are transcribed together as a single mRNA molecule [16]

- Coordinate regulation: All genes in the operon respond coordinately to regulatory signals [16]

- Functional relatedness: Operons often encode enzymes belonging to the same functional pathway [17]

- Chromosomal clustering: Genes are arranged adjacent to one another in the genome [16]

Table 1: Classical Operon Models and Their Regulatory Mechanisms

| Operon | Type | Regulatory Mechanism | Inducer/Corepressor | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lac operon | Inducible | Negative control with positive enhancement by CAP-cAMP | Allolactose (inducer) | Lactose metabolism [16] |

| trp operon | Repressible | Negative feedback repression | Tryptophan (corepressor) | Tryptophan biosynthesis [16] |

| his operon | Repressible | Multiple regulatory inputs | Histidine (corepressor) | Histidine biosynthesis [17] |

The classical view of operons has substantially evolved since its initial conception. While early models suggested operons as simple, self-contained regulatory units, contemporary research recognizes that they exhibit considerable heterogeneity and structural complexity [17]. Many operons are under the control of multiple promoters, regulators, and regulatory sequences, and gene expression can be influenced by organizational features such as translational coupling, polarity effects, and transcription distance [17].

Evolution from Operons to Atomic Regulons: A Gene-Centered Framework

Limitations of Classical Operon-Centric Definitions

The classical operon model, while foundational, presents significant limitations for comprehensive regulon analysis. Traditional definitions are primarily operon-centric, focusing on gene clusters transcribed from a single promoter, but this approach fails to capture the complexity of regulatory networks where transcription factors often coordinate expression across multiple operons and scattered genes [18]. This limitation becomes particularly evident when analyzing global gene regulatory networks, where a single stimulus may trigger expression changes across dozens of chromosomal locations.

Furthermore, prokaryotic genomes demonstrate considerable instability in operon conservation, with only 5-25% of genes belonging to strings shared by at least two distantly related species [17]. This variability suggests that operon conservation might be neutral during evolution, with operon structures showing substantial heterogeneity across bacterial taxa [17]. These limitations necessitated the development of more flexible, gene-centered frameworks that could accommodate the complex reality of bacterial gene regulation.

Atomic Regulons: A Gene-Centered Paradigm

Atomic Regulons (ARs) represent a fundamental shift from operon-centric to gene-centered frameworks for regulon analysis. Defined as sets of genes that have essentially identical expression patterns across diverse conditions, ARs indicate a strong likelihood that member genes are functionally related and coregulated [18]. Each gene belongs to only one AR (some ARs contain single genes), effectively decomposing a genome into its fundamental functional units [18].

The theoretical foundation of ARs aligns with gene-centered evolutionary perspectives, which view evolution through the lens of gene propagation rather than organismal adaptation [19]. From this viewpoint, genes are the primary units of selection, and their clustering in operons or regulons represents a strategy for maximizing their own propagation [19]. This framework provides a powerful approach for understanding the evolutionary forces that shape regulatory networks.

Table 2: Comparison of Gene Regulatory Frameworks

| Feature | Classical Operon | Traditional Regulon | Atomic Regulon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Cluster of genes under control of a single promoter | Set of operons/genes regulated by a common transcription factor | Set of genes with essentially identical expression patterns [18] |

| Gene Membership | Genes are physically adjacent in genome | Genes may be scattered across genome | Genes may be scattered across genome [18] |

| Regulatory Basis | Shared promoter and operator | Shared transcription factor binding sites | Co-expression across diverse conditions [18] |

| Overlap | No overlap between operons | Genes may belong to multiple regulons | Each gene belongs to only one AR [18] |

| Primary Application | Understanding local gene regulation | Mapping transcription factor networks | Defining fundamental functional units of cellular response [18] |

Computational Framework for Atomic Regulon Inference

Algorithm for Atomic Regulon Construction

The computation of Atomic Regulons employs a sophisticated algorithm that integrates multiple data types to identify sets of co-expressed genes. Unlike purely expression-based clustering methods, this approach leverages both genomic context and functional information to improve the biological relevance of the resulting ARs [18]. The algorithm proceeds through six key steps:

Generate Initial Atomic Regulon Gene Sets: Initial clusters are proposed using two independent mechanisms - gene clustering within predicted operons, and membership of genes within functional subsystems [18]

Process Gene Expression Data: All available gene expression data is integrated, normalized, and pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients (PCCs) are computed for all gene pairs [18]

Expression-Informed Splitting: Initial clusters are divided using the criterion that genes in a set must have pairwise expression profiles with PCC > 0.7 [18]

Restrict Gene Membership: Each gene is assigned to exactly one AR, ensuring non-overlapping partitions of the genome [18]

Expression-Informed Merging: Small clusters with highly correlated expression patterns are merged [18]

Final Atomic Regulon Set Construction: The algorithm produces a complete set of ARs representing the fundamental functional units of the cell [18]

Advanced Computational Methods for Regulon Analysis

Recent advances in computational biology have introduced several innovative approaches for regulon analysis that extend beyond traditional methods:

PPA-GCN Framework: The Prokaryotic Pathways Assignment Graph Convolutional Network represents a novel deep learning approach that uses genomic gene synteny information to construct networks from which topological patterns and gene node characteristics can be learned [20]. This framework disseminates node attributes through the network to assist in metabolic pathway assignment, demonstrating how graph-based machine learning can enhance functional annotation [20].

Epiregulon for Single-Cell Multiomics: The Epiregulon method constructs gene regulatory networks from single-cell ATAC-seq and RNA-seq data to accurately predict transcription factor activity [21]. This approach considers the co-occurrence of TF expression and chromatin accessibility at TF binding sites in each cell, enabling inference of TF activity even when decoupled from mRNA expression - particularly valuable for understanding drug effects that disrupt protein complex formation or localization [21].

LexicMap for Large-Scale Sequence Alignment: LexicMap provides efficient nucleotide sequence alignment against millions of prokaryotic genomes, using a novel probing strategy that selects k-mers to efficiently sample entire databases [22]. This tool enables researchers to query sequences against comprehensive genomic databases within minutes, supporting applications across epidemiology, ecology, and evolution [22].

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Computing Atomic Regulons from Expression Data

This protocol details the computational procedure for inferring Atomic Regulons from gene expression data, based on the approach described in the Frontiers in Microbiology article [18].

Materials and Reagents:

- High-quality genome annotation in GFF/GBK format

- RNA-seq or microarray expression data across multiple conditions (minimum 20-30 experiments recommended)

- Computing infrastructure (minimum 8GB RAM for bacterial genomes)

- Bioinformatics software: R or Python with appropriate packages [23]

Procedure:

Data Preparation and Normalization

- Obtain gene expression data from at least 20 different experimental conditions representing diverse environmental perturbations [18]

- Normalize expression data using appropriate methods (e.g., TPM for RNA-seq, RMA for microarrays)

- Compile expression values into a gene × condition matrix with normalized read counts or intensity values

Initial Cluster Formation

- Predict operon structures using intergenic distance methods (typically < 50bp between genes) or tools like Rockhopper [17]

- Group genes into functional categories using existing annotations (e.g., KEGG pathways, SEED subsystems) [18]

- Create initial gene sets based on operon predictions and functional groupings

Expression Correlation Analysis

Atomic Regulon Assignment

Quality Assessment and Validation

- Compare ARs with known regulons from databases like RegulonDB [18]

- Assess biological coherence through functional enrichment analysis

- Evaluate robustness through cross-validation or bootstrap resampling

Troubleshooting:

- Low correlation values may indicate insufficient experimental conditions - expand expression dataset diversity

- Large ARs with mixed functions may require adjustment of correlation threshold

- Genes with inconsistent patterns may require manual inspection or removal as outliers

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation of Predicted Regulons Using Epiregulon

This protocol describes an experimental approach for validating predicted regulons using multiomics data and the Epiregulon computational framework [21].

Materials and Reagents:

- Single-cell multiomics dataset (paired RNA-seq and ATAC-seq)

- ChIP-seq data for transcription factors of interest (optional)

- Epiregulon R package from Bioconductor [21]

- High-performance computing resources for large datasets

Procedure:

Data Preprocessing

GRN Construction with Epiregulon

- For each RE-TG pair, compute weight using co-occurrence method (Wilcoxon test statistic comparing TG expression in "active" cells) [21]

- Construct weighted tripartite graph spanning TFs, REs, and target genes (TGs) [21]

- Define predicted TF activity as the RE-TG-edge-weighted sum of its TGs' expression values [21]

Experimental Validation

- Treat cells with specific TF inhibitors or degraders (e.g., AR antagonists for androgen receptor studies) [21]

- Measure changes in TF activity using Epiregulon predictions compared to expression changes

- Assess specificity by examining predicted TF activity in unrelated cell types

Context-Dependent Interaction Mapping

Research Reagent Solutions for Regulon Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Regulon Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epiregulon R Package | Software | Constructs GRNs from single-cell multiomics data | Uses co-occurrence of TF expression and chromatin accessibility; requires paired RNA-seq/ATAC-seq data [21] |

| PPA-GCN Framework | Deep Learning Model | Assigns metabolic pathways using graph convolutional networks | Leverages genomic gene synteny information; requires sufficient genomes for training [20] |

| LexicMap | Alignment Tool | Efficient nucleotide alignment to millions of genomes | Uses probe k-mers with prefix/suffix matching; optimized for genes, plasmids, long reads [22] |

| ChIP-seq Data | Experimental Data | Maps transcription factor binding sites | ENCODE and ChIP-Atlas provide pre-compiled sites for 1377 factors [21] |

| Single-cell Multiomics | Experimental Platform | Simultaneous measurement of transcriptome and epigenome | Enables inference of TF activity decoupled from mRNA expression [21] |

| Atomic Regulon Algorithm | Computational Method | Identifies always co-expressed gene sets | Integrates operon predictions, subsystems, and expression data (PCC > 0.7) [18] |

Data Analysis and Visualization in Regulon Research

Effective visualization is essential for interpreting complex regulon data and communicating findings. The following approaches represent best practices in the field:

Visualization of Sequence Alignments and Conservation: Tools like Jalview, BioEdit, and Geneious offer advanced features for visualizing sequence alignments, enabling researchers to identify conserved regions, sequence variations, and evolutionary patterns [24]. Sequence logos provide graphical representations that display conservation of residues at each position as well as relative frequency of each amino acid or nucleotide [24].

Expression Data Exploration: The ggplot2 package in R implements a grammar of graphics that enables step-by-step construction of high-quality visualizations for exploring gene expression patterns [25]. SuperPlots are particularly valuable for assessing biological variability, as they combine dot plots and box plots to display individual data points by biological repeat while capturing overall trends [23].

Network Visualization: Graph-based visualizations are essential for representing complex regulatory networks. Tools like Cytoscape enable researchers to visualize interactions within and between regulons, while PyMOL and UCSF Chimera allow visualization of sequence alignments in the context of protein structures [24].

When working with quantitative data in regulon biology, it is crucial to distinguish between data types, as they determine how information is organized, analyzed, and visualized [23]. Continuous data (e.g., fluorescence intensity, expression levels) can take any value within a range, while discrete data (e.g., number of binding sites, operon counts) consist of countable, finite values [23]. Understanding these distinctions helps in selecting appropriate statistical tests and visualization methods.

The evolution from classical operon theory to modern gene-centered frameworks represents a paradigm shift in how we conceptualize and analyze prokaryotic gene regulation. The development of Atomic Regulons as fundamental units of cellular function provides a powerful approach for understanding the modular organization of bacterial genomes and their responses to environmental challenges [18]. This gene-centered perspective aligns with evolutionary theories that view genes as the primary units of selection, with operons and regulons representing strategies for optimizing gene propagation [19].

Future advances in regulon research will likely be driven by several emerging technologies and approaches. Single-cell multiomics methods like Epiregulon will enable more precise mapping of regulatory networks in heterogeneous cell populations [21]. Deep learning frameworks such as PPA-GCN will enhance our ability to predict functional relationships from genomic context [20]. Large-scale alignment tools like LexicMap will facilitate comparative analyses across thousands of microbial genomes, revealing evolutionary patterns in regulon organization [22].

As these technologies mature, they will further solidify the gene-centered paradigm in regulon analysis, providing researchers with increasingly powerful tools to understand, predict, and engineer gene regulatory networks in prokaryotic systems. This knowledge will have profound implications for antibiotic development, metabolic engineering, and our fundamental understanding of microbial life.

The precise distribution of transcription factor (TF) and RNA polymerase (RNAP) binding sites across the genome forms the foundation of transcriptional regulation. In prokaryotes, understanding this landscape is essential for reconstructing regulons—the complete set of genes regulated by a single TF. A gene-centered framework for regulon analysis shifts the focus from operons as single units to individual genes, accommodating the frequent evolutionary reorganization of operons and enabling more accurate cross-species comparisons [26]. This approach, integrated with Bayesian probabilistic methods, allows for the systematic identification of regulatory elements and the prediction of regulon composition directly from genomic sequences, even for newly sequenced bacterial phyla [26] [27]. The following application note details the quantitative data, protocols, and visualization tools essential for applying this gene-centered framework to prokaryotic regulon analysis.

Quantitative Landscape of TF and RNAP Binding

Positional Distribution of Transcription Factor Binding Sites

Comprehensive analysis of TF binding sites (TFBSs) reveals a non-random genomic distribution. A recent large-scale study using ENCODE ChIP-seq data for 500 human TFs provides a model for understanding general principles of TF binding, which can inform prokaryotic studies. The data show that while the majority of TFBSs are located in intronic (42.6%) and intergenic (31.6%) regions, promoter regions exhibit the highest TFBS density [28].

Table 1: Genomic Distribution of Transcription Factor Binding Sites

| Genomic Region | Percentage of Total TFBSs | Relative Binding Site Density |

|---|---|---|

| Promoters | 11.3% | High (Bell-shaped peak at TSS) |

| Introns | 42.6% | Moderate |

| Intergenic | 31.6% | Moderate |

| Other | 14.5% | Low |

The distribution of TFBSs in promoter regions follows a bell-shaped curve with a distinct peak approximately 50 base pairs upstream of the transcription start site (TSS) [28]. This pattern underscores the importance of core promoter regions in transcriptional regulation across evolutionary domains.

RNA Polymerase as a Marker of Active Regulatory Elements

The co-occurrence of RNAP with TF binding events serves as a critical discriminator between active and inactive regulatory sites. Functional assays demonstrate that TF-bound sites coinciding with promoter-distal RNAP binding are significantly more likely to exhibit enhancer activity than those devoid of RNAP [29]. This principle, while established in eukaryotic systems, provides a valuable framework for identifying functional regulatory elements in prokaryotes through the detection of RNAP co-localization.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Comparative Genomics of Prokaryotic Regulons Using CGB Pipeline

The CGB (Comparative Genomics of Bacteria) pipeline enables the reconstruction of transcriptional regulatory networks using a gene-centered Bayesian framework [26].

Input Preparation and Requirements

- Input Format: JSON-formatted file containing NCBI protein accession numbers for reference TFs and aligned binding sites

- Genome Data: Accession numbers for complete chromosomes or contigs from target species

- Configuration Parameters: Prior probability settings, phylogenetic analysis parameters

Computational Workflow

- Ortholog Identification: Detect TF orthologs in each target genome using reference TF instances

- Phylogenetic Tree Construction: Generate a tree of TF instances to estimate evolutionary distances

- Position-Specific Weight Matrix (PSWM) Generation: Create weighted mixture PSWMs for each target species using CLUSTALW-like weighting based on phylogenetic distances [26]

- Operon Prediction: Predict operon structures in each target species

- Promoter Scanning: Identify putative TF-binding sites in promoter regions and estimate posterior probabilities of regulation

- Ortholog Group Prediction: Identify groups of orthologous genes across target species

- Ancestral State Reconstruction: Estimate aggregate regulation probability using phylogenetic methods

Bayesian Framework for Regulation Probability

The probability of regulation is calculated using a Bayesian framework that compares score distributions in regulated versus non-regulated promoters [26]:

For a promoter with observed scores ( D ), the posterior probability of regulation ( P(R|D) ) is: [ P(R|D) = \frac{P(D|R)P(R)}{P(D|R)P(R) + P(D|B)P(B)} ] where:

- ( P(D|R) ) is the likelihood function for regulated promoters

- ( P(D|B) ) is the likelihood function for background promoters

- ( P(R) ) and ( P(B) ) are prior probabilities of regulated and background states

The likelihood functions are derived from mixture distributions combining background genome statistics and TF-binding motif statistics [26].

Protocol: Functional Validation of RNAP-Associated TF Binding Sites

This protocol adapts the principles from eukaryotic functional assays [29] for prokaryotic systems to validate regulatory activity.

Identification of Co-occurring Binding Sites

- Perform Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq) or similar genomic binding assays for the TF of interest and RNAP

- Identify reproducible binding events across biological replicates

- Define co-occurring sites as TF-bound regions that overlap with RNAP binding within a specified distance threshold

Functional Reporter Assay

- Clone DNA sequences underlying TF binding sites with and without RNAP co-occurrence into reporter vectors

- Transfer constructs into target bacterial cells

- Measure reporter gene expression under appropriate conditions

- Compare activity between RNAP-associated and RNAP-devoid TF binding sites

Visualization of Regulatory Networks

Comparative Genomics Workflow for Regulon Analysis

Bayesian Classification Framework for Regulon Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Genomic Binding and Regulon Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| CGB Pipeline [26] | Comparative reconstruction of bacterial regulons | Gene-centered analysis; Bayesian probability framework; Flexible genome input |

| ENCODE ChIP-seq Data [28] [30] | Reference TF binding profiles | High-quality data from multiple cell types; Standardized processing pipelines |

| Position-Specific Weight Matrix (PSWM) | Representation of TF binding specificity | Captures nucleotide preferences at each position; Enables genome scanning |

| MEME-ChIP [28] | De novo motif discovery from ChIP-seq data | Identifies multiple motifs in peak sequences; Quality assessment tools |

| RNAP Antibodies [29] | Immunoprecipitation of RNA polymerase complexes | Enrichment of active regulatory elements; Discriminates functional TF binding |

| CAP-SELEX [31] | Identification of cooperative TF-TF interactions | Reveals spacing and orientation preferences; Discovers composite motifs |

| SW157765 | SW157765, MF:C19H13N3O3, MW:331.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Bax-IN-1 | Bax-IN-1, MF:C16H14N6O, MW:306.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Prokaryotes exist in dynamically changing environments where they must constantly sense, integrate, and respond to multiple simultaneous signals to ensure survival. This sophisticated processing occurs through interconnected regulatory networks that enable bacteria to coordinate gene expression in response to environmental challenges. The conceptual understanding of these networks has evolved significantly from early models of simple operons to contemporary gene-centered frameworks that reveal a complex, hierarchical architecture governing cellular decision-making [32].

At its core, bacterial signal integration represents a computational challenge where limited resources must be allocated to maximize fitness. A prokaryotic cell must process diverse inputs including nutrient availability, temperature fluctuations, osmotic stress, quorum signals, and oxidative stress through a network of transcription factors, small RNAs, and second messengers. The output of this computation is a tailored gene expression profile that enables adaptation without overwhelming the cell's biosynthetic capacity. Understanding these networks is crucial not only for fundamental microbiology but also for applications in antibiotic development, bioremediation, and synthetic biology [33].

Hierarchical Organization of Prokaryotic Regulatory Networks

The Functional Units of Genetic Regulation

Prokaryotic regulatory networks are organized into precisely defined functional units that operate at different levels of complexity. This hierarchical organization enables efficient coordination of gene expression from specific metabolic pathways to global stress responses [32].

Operons: As the fundamental unit of coordination, operons comprise physiologically related genes transcribed as a single polycistronic mRNA unit. This organization allows for the coregulation of proteins that function together in metabolic pathways or structural complexes. Approximately half of E. coli genes are organized in operons, representing the most basic level of transcriptional coordination [32].

Regulons: A regulon encompasses multiple operons or genes scattered throughout the chromosome that are coregulated by the same specific regulatory protein. The classic example is the arginine biosynthetic regulon, where dispersed operons are all controlled by the ArgR repressor protein. This organization enables coordinated expression of functionally related genes that cannot be physically linked in a single operon [32].

Modules: Modules represent a higher level of organization where groups of genes cooperate to achieve a particular physiological function. Modules often incorporate multiple regulons and operons into functional units dedicated to complex processes such as flagellar assembly, sporulation, or stress response. These modules exhibit a matryoshka-like nesting property, with smaller modules embedded within larger functional units [32].

Global Transcription Factors: Sitting at the top of the regulatory hierarchy, global transcription factors coordinate multiple modules in response to general environmental cues. These factors regulate many genes participating in more than one metabolic pathway and serve as master coordinators of cellular physiology. In the business analogy of cellular regulation, they function as "general managers" responsible for integrating wide-scope directives [32].

Network Architecture and Coordination Principles

The integration of these hierarchical components forms a non-pyramidal network architecture with extensive feedback and cross-regulation. Research by Freyre-González et al. has identified four key functional components that shape this architecture through natural decomposition analysis [32]:

- Global transcription factors that coordinate specialized cell functions using broad signals

- Strictly globally regulated genes that respond only to broad, non-specific directives

- Modular genes organized into departments devoted to particular cellular functions

- Intermodular genes that act as specialized task forces integrating signals from different modules

This architecture enables signal processing fidelity through network motifs such as feedforward loops, negative feedback loops, and mutual inhibition circuits. For example, in the σS control network of E. coli, multiple feedforward loops control σS expression, while a central homeostatic negative feedback loop integrates post-transcriptional control mechanisms. Mutual inhibition of sigma factors competing for RNA polymerase core enzyme governs activity control, and positive feedback loops stabilize the high-σS state during stress response [32] [33].

Gene-Centered Frameworks for Regulon Analysis

Evolution from Operon-Centered to Gene-Centered Approaches

Traditional comparative genomics approaches have focused on the operon as the fundamental unit of regulation. However, this paradigm faces limitations due to the frequent reorganization of operons across bacterial species and strains. After an operon split, genes originally in the same operon may remain regulated by the same transcription factor through independent promoters, creating challenges for operon-centered analysis [26].

The gene-centered framework represents a significant methodological evolution that addresses these limitations. In this approach, operons remain important as logical units of regulation, but the comparative analysis and reporting of regulons is based on the gene as the fundamental unit. This enables more accurate assessment of the regulatory state of each gene while still providing detailed information on operon organization in each organism [26].

The CGB Platform for Comparative Genomics

The CGB (Comparative Genomics of Bacterial regulons) platform implements a complete computational workflow for comparative reconstruction of bacterial regulons using available knowledge of transcription factor-binding specificity. This flexible platform enables fully customized analyses of newly available genome data with minimal external dependencies [26].

Table 1: Key Features of the CGB Platform for Gene-Centered Regulon Analysis

| Feature | Description | Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Gene-Centered Analysis | Uses genes rather than operons as fundamental regulatory units | Accommodates frequent operon reorganization across species |

| Automated Information Transfer | Transfers TF-binding motif information from multiple sources across target species | Eliminates need for manual adjustment of TF-binding sites |

| Bayesian Probabilistic Framework | Estimates posterior probabilities of regulation for each gene | Provides easily interpretable, comparable results across species |

| Species-Specific Weight Matrices | Generates weighted mixture PSWM in each target species based on phylogenetic distance | Accounts for evolutionary divergence in binding specificity |

| Ancestral State Reconstruction | Integrates aggregate regulation probability across orthologous groups | Enables evolutionary inference of regulon development |

The platform automates the merging of experimental information from multiple sources and uses a formal Bayesian framework to generate easily interpretable results. A key innovation is the handling of TF-binding motif information transfer across evolutionary distances. CGB estimates a phylogeny of reference and target TF orthologs, using inferred distances to generate weighted mixture position-specific weight matrices (PSWMs) in each target species, following the weighting approach used in CLUSTALW [26].

Bayesian Framework for Regulation Probability

CGB implements a sophisticated Bayesian probabilistic framework for estimating posterior probabilities of gene regulation. This approach addresses limitations of traditional position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM) cut-off methods, which are poorly suited for comparative genomics due to varying oligomer distributions in different bacterial genomes [26].

The framework defines two distributions of PSSM scores within a promoter region:

- Background distribution (B): The expected score distribution in a promoter not regulated by the TF, approximated using a normal distribution parametrized by genome-wide PSSM statistics

- Regulated distribution (R): The expected score distribution in a regulated promoter, approximated as a mixture of both the background distribution and the distribution of scores in functional sites

For any given promoter, the posterior probability of regulation P(R|D) given the observed scores (D) is calculated using Bayes' theorem, providing a statistically rigorous foundation for predicting regulatory relationships [26].

Experimental Protocols for Regulon Analysis

Protocol 1: Computational Reconstruction of Regulons Using CGB

This protocol details the steps for comparative reconstruction of bacterial regulons using the CGB platform, enabling researchers to map regulatory networks across multiple bacterial genomes [26].

Experimental Setup and Input Preparation

Step 1: Input Configuration: Prepare a JSON-formatted input file containing:

- NCBI protein accession numbers and list of aligned binding sites for at least one transcription factor instance

- Accession numbers for chromids or contigs mapping to one or more target species

- Configuration parameters for the analysis

Step 2: Data Collection: Collect available TF-binding site information from reference organisms. Ensure collections of TF-binding sites for each TF instance are aligned, with compatible PSWM dimensions. This alignment can be performed manually or using dedicated tools.

Step 3: Ortholog Identification: Use reference TF-instances to detect orthologs in each target genome. The platform will automatically generate a phylogenetic tree of TF instances to guide subsequent analysis.

Computational Analysis Pipeline

Step 4: Weight Matrix Generation: The phylogenetic tree is used to combine available TF-binding site information into a position-specific weight matrix (PSWM) for each target species. The algorithm uses inferred evolutionary distances to generate weighted mixture PSWMs.

Step 5: Operon Prediction: Predict operons in each target species using integrated algorithms. The gene-centered framework will maintain information on operon organization while using genes as the fundamental unit for regulatory analysis.

Step 6: Promoter Scanning: Scan promoter regions to identify putative TF-binding sites and estimate their posterior probability of regulation using the Bayesian framework described in section 3.3.

Step 7: Ortholog Group Analysis: Predict groups of orthologous genes across target species and estimate their aggregate regulation probability using ancestral state reconstruction methods.

Output Generation and Interpretation

Step 8: Result Compilation: The platform outputs multiple CSV files reporting:

- Identified binding sites with positional information and scores

- Ortholog groups with regulation probabilities

- Derived PSWMs for each target species

- Posterior probabilities of regulation for each gene

Step 9: Visualization: Generate plots depicting hierarchical heatmaps and tree-based ancestral probabilities of regulation. These visualizations facilitate interpretation of complex regulatory relationships across species.

Step 10: Biological Validation: Although computational predictions provide valuable hypotheses, essential validation steps include:

- Experimental verification of key predicted regulatory interactions

- Cross-referencing with existing regulon databases

- Functional assessment through mutagenesis of predicted binding sites

Protocol 2: Experimental Analysis of Signal Integration in Bacterial Stress Response

This protocol outlines experimental approaches for characterizing how prokaryotes integrate multiple environmental signals through regulatory networks, using the σS-controlled general stress response in E. coli as a model system [32] [33].

Growth Conditions and Stress Application

Step 1: Culture Conditions: Grow E. coli cultures in defined minimal medium under precisely controlled conditions. Avoid complex media to prevent unintended signal interference.

Step 2: Signal Application: Apply specific stress signals in controlled combinations:

- Nutritional stress: Stationary phase entry through carbon source depletion

- Oxidative stress: Sublethal concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (0.1-0.5 mM)

- Osmotic stress: Addition of NaCl to final concentrations of 0.2-0.4 M

- Temperature stress: Shift to suboptimal growth temperatures (20°C or 42°C)

Step 3: Time-Course Sampling: Collect samples at multiple time points following stress application (0, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes) to capture dynamics of signal integration.

Molecular Analysis of Regulatory Response

Step 4: σS Measurement: Quantify σS levels at different regulatory checkpoints:

- Transcript levels: Northern blot or RT-qPCR for rpoS mRNA

- Translation efficiency: LacZ reporter fusions with rpoS translational regulators

- Protein stability: Western blot analysis with proteolysis inhibitors

- RNAP holoenzyme formation: Co-immunoprecipitation of σS with RNAP core

Step 5: Target Gene Expression: Monitor expression of key σS-dependent genes using transcriptional fusions or mRNA quantification. Select genes representing different functional categories within the σS regulon.

Step 6: Network Motif Identification: Analyze regulatory circuits for characteristic network motifs:

- Feedforward loops: Identify regulators that control both σS and its target genes

- Negative feedback: Assess autoregulatory loops in σS control

- Mutual inhibition: Test competition between σS and other sigma factors

- Positive feedback: Identify stabilizers of the high-σS state

Research Reagent Solutions for Prokaryotic Regulatory Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Prokaryotic Regulatory Network Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | CGB Platform, RegulonDB, SCENIC | Comparative regulon reconstruction, network analysis, and visualization |

| Database Resources | GREDB, BioGRID, TRRUST, RegNetwork | Experimentally validated gene regulatory relationships and interactions |

| Sequence Analysis | GENIE3, SDNE, BLAST | Inference of regulatory relationships from sequence data and expression patterns |

| Experimental Model Systems | E. coli K-12, Bacillus subtilis, Salmonella typhimurium | Well-characterized model organisms with extensive regulatory network annotations |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | β-galactosidase reporters, chromatin immunoprecipitation, bacterial two-hybrid systems | Experimental validation of regulatory interactions and network architecture |

Signaling Pathways in Prokaryotic Regulatory Networks

Major Regulatory Systems and Their Integration Points

Prokaryotes employ several specialized regulatory systems that integrate environmental signals into coordinated transcriptional responses. The major systems include:

Two-Component Regulatory Systems: These ubiquitous signaling pathways consist of a sensor kinase that autophosphorylates in response to environmental stimuli and a response regulator that mediates changes in gene expression upon phosphorylation. TCSs represent the dominant mechanism for stimulus-responsive adaptation in prokaryotes, regulating diverse processes including cell cycle progression, pathogenesis, motility, and biofilm formation [33].

Alternative Sigma Factors: Sigma factors associate with RNA polymerase core enzyme to direct it to specific promoter sequences. The largest group of alternative sigma factors consists of extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors that regulate gene expression in response to cell envelope stresses or environmental stimuli. Their activity is controlled by anti-sigma factors and complex cascades of regulated proteolytic modifications [33].

Quorum Sensing Systems: Bacteria regulate gene expression in a population-dependent manner using chemical signals known as autoinducers. While N-acyl derivatives of homoserine lactones (AHLs) predominate in Gram-negative bacteria, a wide variety of signals are used across species. This synchronized response enables bacterial populations to exhibit a form of multicellularity, adapting to challenging environments through coordinated behavior [33].

Nucleotide Second Messenger Systems: Cyclic di-GMP is recognized as an almost universal second messenger in eubacteria that regulates diverse functions including developmental transitions, adhesion, biofilm formation, motility, and virulence factor synthesis. The multiplicity of synthetic (diguanylate cyclases with GGDEF domains) and degradative (phosphodiesterases with EAL or HD-GYP domains) enzymes indicates considerable complexity in cyclic di-GMP signaling, leading to the concept of discrete nucleotide pools that act locally on intimately associated targets [33].

Visualization of Prokaryotic Signal Integration Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the core architecture of signal integration in prokaryotic regulatory networks, highlighting the hierarchical organization and key regulatory components:

The σS control network in E. coli provides a well-characterized example of how multiple stress signals are integrated through interconnected regulatory motifs:

Quantitative Analysis of Regulatory Networks

Performance Metrics for Regulatory Network Inference

The evaluation of computational tools for regulon reconstruction requires multiple metrics to comprehensively quantify effectiveness across diverse data scenarios. Benchmarking studies typically employ several performance indicators to assess prediction accuracy and biological relevance [26] [34].

Table 3: Performance Metrics for Regulatory Network Inference Tools

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Proportion of correct predictions among total predictions | Overall correctness of regulatory assignments | 0.70-0.99 |

| Precision | Proportion of true positives among all positive predictions | Ability to avoid false positive predictions | 0.65-0.95 |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | Proportion of actual positives correctly identified | Ability to identify all true regulatory relationships | 0.60-0.95 |

| F1-Score | Harmonic mean of precision and recall | Balanced measure of prediction performance | 0.65-0.95 |

| Matthew's Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | Correlation coefficient between observed and predicted classifications | Comprehensive measure considering all confusion matrix categories | 0.60-0.95 |

Recent benchmarking of the scHGR tool for gene regulatory network-aware cell annotation demonstrated superior performance across multiple metrics, achieving F1-scores approximately 5% higher than second-place methods and precision/recall values 23-24% higher than comparative approaches in specific datasets [34].

Statistical Framework for Regulation Probability Estimation

The Bayesian probabilistic framework implemented in platforms like CGB enables estimation of posterior probabilities of regulation through formal statistical modeling. The key parameters and distributions include [26]:

Table 4: Parameters for Bayesian Probability Estimation of Gene Regulation

| Parameter | Symbol | Estimation Method | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Background Distribution | B ~ N(μG, σG²) | Genome-wide statistics of PSSM scores | Expected score distribution in non-regulated promoters |

| Motif Distribution | M ~ N(μM, σM²) | Statistics of known TF-binding sites | Expected score distribution in functional binding sites |

| Mixing Parameter | α | 1/average promoter length | Prior probability of functional site presence |

| Regulated Distribution | R ~ αM + (1-α)B | Mixture distribution | Expected score distribution in regulated promoters |

| Posterior Probability | P(R|D) | Bayesian inference from observed scores | Probability that a promoter is regulated given sequence data |

This formal statistical framework provides several advantages over traditional cutoff-based methods, including interpretable probability estimates, adaptability to different genomic backgrounds, and principled integration of evolutionary information in comparative genomics analyses [26].

Application Notes for Drug Development

Targeting Regulatory Networks for Antimicrobial Development

The sophisticated architecture of prokaryotic regulatory networks presents attractive targets for novel antimicrobial strategies. Rather than targeting essential metabolic functions, disrupting bacterial signal integration and response coordination can impair adaptability and virulence without imposing immediate lethal pressure [33].

Key strategic approaches include:

Quorum Sensing Interference: Many pathogens including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Vibrio cholerae rely on quorum sensing systems to coordinate virulence factor production and biofilm formation. Small molecule inhibitors of autoinducer synthesis, detection, or signal integration can disarm pathogenic capabilities without affecting growth, potentially reducing selection for resistance [33].

Nucleotide Second Messenger Modulation: The cyclic di-GMP signaling network regulates the transition between motile and sessile lifestyles in numerous bacterial pathogens. Compounds that selectively inhibit diguanylate cyclases or stimulate phosphodiesterases could prevent biofilm formation, enhancing antibiotic penetration and immune clearance. The multiplicity of GGDEF/EAL/HD-GYP domain proteins provides potential for pathogen-specific targeting [33].

Sigma Factor Antagonism: The coordination of alternative sigma factors through competitive binding to RNA polymerase core enzyme creates vulnerable points in regulatory networks. Factors controlling virulence and stress response, such as σ54 and ECF sigma factors, represent promising targets for small molecules that disrupt their association with RNAP or activation mechanisms [33].

Two-Component System Inhibition: Histidine kinase inhibitors represent a well-established approach to disrupting bacterial signal transduction. The conserved nature of kinase domains challenges specificity, but structural insights are enabling more selective targeting of pathogen-specific systems controlling virulence, antibiotic resistance, and persistence [33].

Diagnostic Applications of Regulatory Network Knowledge

Understanding pathogen regulatory networks enables development of sophisticated diagnostic approaches that move beyond simple pathogen detection to functional assessment of virulence potential and antibiotic susceptibility.

Promising applications include:

Regulon Activation Profiling: Transcriptional profiling of key regulons can indicate which adaptive programs a pathogen is deploying during infection. For example, simultaneous activation of iron limitation, oxidative stress, and nutrient starvation regulons might indicate aggressive host adaptation, informing prognosis and treatment intensity [34].

Network-Based Resistance Prediction: Analysis of regulatory networks controlling efflux pumps, biofilm formation, and persistence mechanisms can predict emerging resistance patterns before they manifest at phenotypic levels. Integration of regulatory mutations with traditional resistance markers enhances predictive accuracy [26] [34].

Host-Pathogen Communication Mapping: Dual RNA-seq approaches simultaneously capturing host and pathogen transcriptomes reveal how bacterial regulatory networks respond to specific host defense mechanisms and how host pathways react to bacterial virulence factors, guiding immunomodulatory therapies [34].