From Prediction to Proof: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Regulon Predictions in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to validate computational predictions of regulons—the complete set of regulatory elements controlled by a transcription factor.

From Prediction to Proof: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Regulon Predictions in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to validate computational predictions of regulons—the complete set of regulatory elements controlled by a transcription factor. It bridges the gap between in silico predictions and experimental confirmation, covering foundational concepts, state-of-the-art computational methodologies, strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing current approaches from single-cell multiomics to machine learning and cross-species transfer, this guide aims to enhance the reliability of regulatory network models for accelerating therapeutic discovery and understanding disease mechanisms.

Understanding Regulons: The Blueprint of Cellular Regulation and Why Validation Matters

Defining Regulons and Cis-Regulatory Modules in Transcriptional Networks

Gene regulatory networks are fundamental to cellular function, development, and disease. Two fundamental concepts in understanding these networks are regulons and cis-regulatory modules (CRMs). A regulon refers to a set of genes or operons co-regulated by a single transcription factor (TF) across the genome, representing the trans-acting regulatory scope of that TF [1]. In contrast, a cis-regulatory module (CRM) is a localized region of non-coding DNA, typically 100-1000 base pairs in length, that integrates inputs from multiple transcription factors to control the expression of a nearby gene [2] [3]. CRMs include enhancers, promoters, silencers, and insulators that determine when, where, and to what extent genes are transcribed [3].

The distinction between these concepts forms a foundational framework for research aimed at validating regulon predictions. While regulons define the complete set of targets for a given TF, CRMs represent the physical DNA sequences through which this regulation is executed. This article compares the defining characteristics of regulons and CRMs, evaluates computational and experimental methods for their identification, and provides a practical toolkit for researchers validating regulon predictions through experimental approaches.

Defining Characteristics and Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Regulons and Cis-Regulatory Modules

| Feature | Regulon | Cis-Regulatory Module (CRM) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Set of operons/genes co-regulated by a single transcription factor [1] | Cluster of transcription factor binding sites that function as a regulatory unit [2] [3] |

| Regulatory Scope | Genome-wide, targeting multiple loci [1] | Local, typically regulating adjacent gene(s) [2] |

| Primary Function | Coordinate expression of functionally related genes in response to cellular signals [1] | Integrate multiple transcriptional inputs to determine spatial/temporal expression patterns [2] [4] |

| Size/Scale | Multiple operons scattered throughout genome [1] | 100-1000 base pairs of DNA sequence [2] [3] |

| Key Components | Transcription factor + its target genes/operons [1] | Clustered transcription factor binding sites [2] |

| Information Processing | Implements single-input decision making [1] | Performs combinatorial integration of multiple inputs [2] [4] |

| Conservation | Often lineage-specific with rapid evolution | Sequence modules may be conserved with binding site variation |

The relationship between these entities can be visualized as a hierarchical regulatory network:

Figure 1: Hierarchical organization of transcriptional regulation. A transcription factor regulates a regulon consisting of multiple genes through their individual cis-regulatory modules.

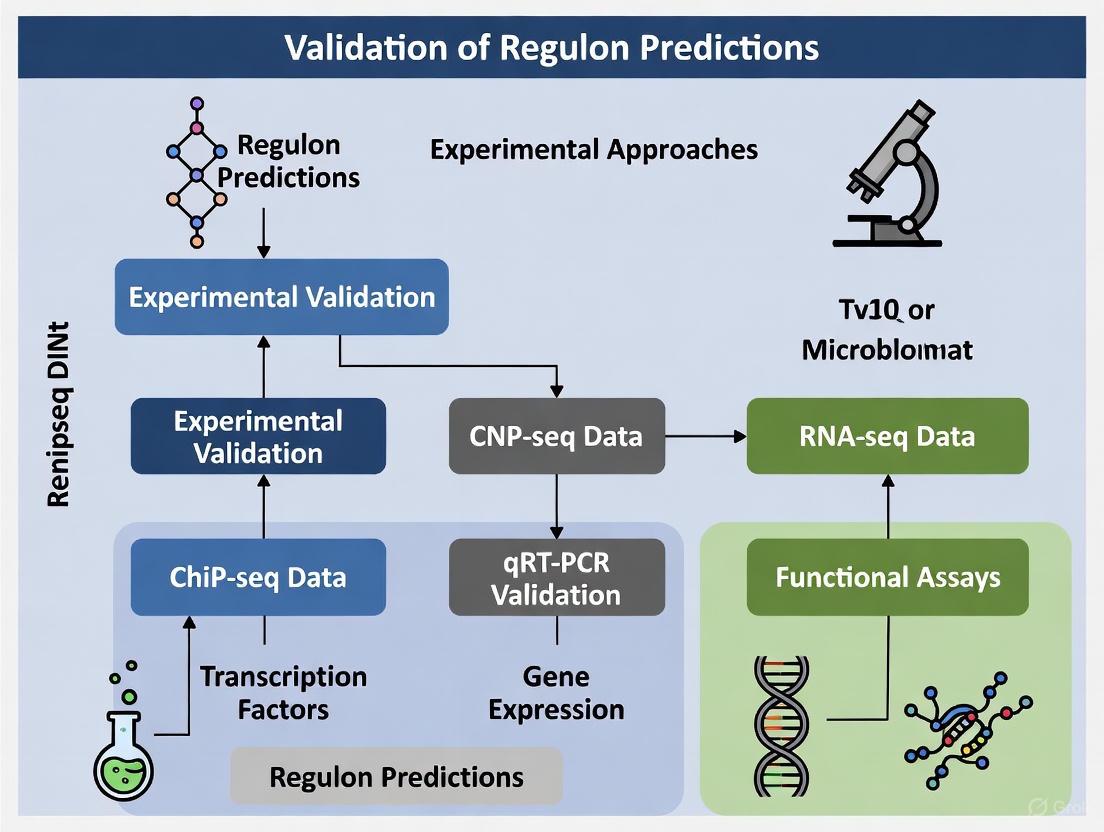

Experimental Approaches for Validation

Computational Prediction Methods

Table 2: Computational Methods for Regulon and CRM Prediction

| Method Type | Underlying Principle | Typical Data Sources | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature-Curated Resources | Manually collected interactions from published studies [5] | Experimental data from peer-reviewed literature | High-quality, experimentally validated interactions [5] | Biased toward well-studied TFs; limited coverage [5] |

| ChIP-seq Binding Data | Genome-wide mapping of TF binding sites [5] [4] | Chromatin immunoprecipitation with sequencing | High-resolution in vivo binding maps [5] | Many binding events may be non-functional; cell type-specific [5] |

| TFBS Prediction | Scanning regulatory regions with position weight matrices [5] [4] | TF binding motifs from databases (JASPAR, HOCOMOCO) | Not limited by experimental conditions; comprehensive [5] | High false positive rate; depends on motif quality [5] [4] |

| Expression-Based Inference | Reverse engineering from gene expression correlations [5] | Large-scale transcriptomics data (e.g., GTEx, TCGA) | Captures context-specific regulation [5] | Cannot distinguish direct vs. indirect regulation [5] |

| Phylogenetic Footprinting | Identification of evolutionarily conserved non-coding regions [4] [1] | Comparative genomics across multiple species | High specificity for functional elements [4] | Limited to conserved regions; reference genome dependent [1] |

Experimental Validation Workflows

Systematic validation of predicted regulons and CRMs requires integrated experimental workflows that combine computational predictions with empirical testing:

Figure 2: Sequential workflow for experimental validation of predicted regulons and CRMs.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq) provides high-resolution mapping of transcription factor binding sites genome-wide [5] [4]. The protocol involves: (1) crosslinking proteins to DNA with formaldehyde, (2) shearing chromatin by sonication, (3) immunoprecipitating protein-DNA complexes with TF-specific antibodies, (4) reversing crosslinks, and (5) sequencing bound DNA fragments. ChIP-seq peaks indicate direct physical binding but require functional validation as not all binding events regulate transcription [5].

Reporter Assays test the regulatory activity of predicted CRMs by cloning candidate sequences into vectors driving expression of detectable reporters (e.g., GFP, luciferase) [4]. The experimental workflow includes: (1) amplifying candidate CRM sequences, (2) cloning into reporter vectors, (3) transfection into relevant cell types, (4) measuring reporter expression under different conditions, and (5) comparing to minimal promoter controls. This approach directly demonstrates enhancer activity but removes genomic context [4].

CRISPR-Based Functional Validation assesses the necessity of specific CRMs for gene expression by deleting or perturbing regulatory sequences in their native genomic context [4]. The methodology involves: (1) designing guide RNAs targeting predicted CRMs, (2) delivering CRISPR components to cells, (3) validating edits by sequencing, (4) measuring expression changes of putative target genes, and (5) assessing phenotypic consequences. This approach provides strong evidence for CRM function but may be complicated by redundancy among multiple CRMs regulating the same gene [2].

Performance Comparison of Prediction Methods

Table 3: Benchmarking of TF-Target Interaction Evidence Types

| Evidence Type | Sensitivity | Specificity | Coverage | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature-Curated | Moderate | High | Low (biased toward well-studied TFs) [5] | Benchmarking; high-confidence network construction [5] |

| ChIP-seq | High | Moderate | Moderate (cell type-specific) [5] | Cell type-specific regulatory networks [5] |

| TFBS Prediction | High | Low | High (motif-dependent) [5] | Initial screening; TFs with well-defined motifs [5] |

| Expression-Based Inference | Moderate | Moderate | High (context-specific) [5] | Condition-specific networks; novel context prediction [5] |

| Integrated Approaches | High | High | Moderate to High | Comprehensive network modeling [6] |

Systematic benchmarking studies have evaluated how different evidence types support accurate TF activity estimation. In comprehensive assessments, literature-curated resources followed by ChIP-seq data demonstrated the best performance in predicting changes in TF activities in reference datasets [5]. However, each method shows distinct biases and coverage limitations, suggesting that integrated approaches provide the most robust predictions.

Advanced methods like Epiregulon leverage single-cell multiomics data (paired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq) to construct gene regulatory networks by evaluating the co-occurrence of TF expression and chromatin accessibility at binding sites in individual cells [6]. This approach accurately predicted drug response to AR antagonists and degraders in prostate cancer cell lines, successfully identifying context-dependent interaction partners and drivers of lineage reprogramming [6].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Regulon and CRM Validation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Research Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| TF Binding Site Databases | JASPAR [5], HOCOMOCO [5] | Position weight matrices for TFBS prediction | Computational identification of CRM sequences [5] |

| Curated Interaction Databases | RegulonDB [7] [1], ENCODE [6], ChIP-Atlas [6] | Experimentally validated TF-target interactions | Benchmarking predictions; prior knowledge integration [5] |

| Chromatin Profiling Kits | ChIP-seq kits (e.g., Cell Signaling Technology, Abcam) | Genome-wide mapping of protein-DNA interactions | Experimental validation of TF binding [5] [4] |

| Reporter Vectors | Luciferase (pGL4), GFP vectors | Modular plasmids for cloning candidate CRMs | Functional testing of enhancer/promoter activity [4] |

| CRISPR Systems | Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes | Precise genome editing of regulatory elements | In situ validation of CRM necessity [4] |

| Multiomics Platforms | 10x Multiome (ATAC + RNA), SHARE-seq | Simultaneous measurement of chromatin accessibility and gene expression | Single-cell regulatory network inference [6] |

| TF Activity Inference Tools | VIPER [7], Epiregulon [6] | Computational estimation of TF activity from expression data | Regulon activity assessment across conditions [7] [6] |

| Antibacterial agent 53 | Antibacterial agent 53, MF:C15H17N5O6S, MW:395.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Benzyl 2-Hydroxy-6-Methoxybenzoate | Benzyl 2-Hydroxy-6-Methoxybenzoate, CAS:24474-71-3, MF:C15H14O4, MW:258.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Validating regulon predictions requires a multimodal approach that combines computational predictions with experimental testing. The most effective strategies integrate multiple evidence types - literature curation, binding data, motif analysis, and expression correlations - to generate high-confidence regulon maps [5]. Experimental validation should progress through a sequential workflow from reporter assays to genome editing, with particular emphasis on testing predictions in relevant cellular contexts and physiological conditions.

Emerging technologies in single-cell multiomics [6] and CRISPR-based functional genomics are rapidly advancing our ability to map and validate regulons and CRMs at unprecedented resolution. These approaches are particularly valuable for understanding context-specific regulation in disease states and during dynamic processes like development and drug response. As these methods mature, they will increasingly enable researchers to move beyond static regulon maps toward dynamic models of transcriptional network regulation that can accurately predict cellular responses to genetic and environmental perturbations.

In the fields of bioinformatics and systems biology, a frequent and critical question posed to researchers is whether their computational results have been experimentally validated [8]. This question, often laden with cynicism, highlights a fundamental communication gap and a misunderstanding of the complementary roles that computational and experimental methods play. The phrase "experimental validation" itself is problematic, as the term 'validation' carries connotations of proving, authenticating, or legitimizing, which can misrepresent the scientific process [8]. A more accurate framing recognizes that computational models are logical systems built upon a priori empirical assumptions, and the role of experimental data is better described as calibration or corroboration rather than validation [8]. This article explores this critical gap, focusing specifically on the challenge of regulon prediction in bacterial genomics, and provides a comparative guide for assessing different prediction and validation methodologies.

The Regulon Prediction Challenge: Computational Methods and Limitations

A regulon is a fundamental unit of a bacterial cell's response system, defined as a maximal set of transcriptionally co-regulated operons that may be scattered throughout the genome without apparent locational patterns [1]. Elucidating regulons is essential for reconstructing global transcriptional regulatory networks, understanding gene function, and studying evolution [1]. However, exhaustively identifying all regulons experimentally is costly, time-consuming, and practically infeasible because it requires testing under all possible conditions that might trigger each regulon [1]. This has driven the development of computational prediction methods, which generally fall into two categories:

- Prediction of new operon members for a known regulon: This approach searches for new binding sites based on existing motif profiles from databases like RegulonDB [1].

- Ab initio inference of novel regulons: This method uses de novo motif finding to predict regulons without prior knowledge, typically involving operon identification, motif prediction, and clustering [1].

Despite advances, computational regulon prediction faces significant challenges, including high false-positive rates in de novo motif prediction, unreliable motif similarity measurements, and limitations in operon prediction algorithms [1]. The core problem is that these methods are inferences based on genomic sequence data and evolutionary principles, and they require corroboration to assess their biological accuracy.

Comparative Analysis of Computational Regulon Prediction Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Core Computational Approaches for Predicting Functional Interactions in Regulons

| Method | Core Principle | Key Metric | Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conserved Operons [9] [1] | Identifies genes consistently located together in operons across different organisms. | Evolutionary distance score for conserved gene pairs [9]. | High utility for predicting coregulated sets; leverages evolutionary conservation. | Gene order in closely related genomes may be conserved for reasons other than coregulation [9]. |

| Protein Fusions (Rosetta Stone) [9] | Infers functional interaction if two separate proteins in one organism are fused into a single polypeptide in another. | Weighted score based on BLAST E-values of the non-overlapping hits [9]. | Suggests direct functional partnership or involvement in a common pathway. | Can produce false positives due to common domains; requires careful parameter tuning [9]. |

| Correlated Evolution (Phylogenetic Profiles) [9] [1] | Identifies genes whose homologs are consistently present or absent together across a set of genomes. | Partial Correlation Score (PCS) based on presence/absence vectors [1]. | Reflects evolutionary pressure to maintain entire pathways as a unit. | Performance depends on the number and selection of reference genomes. |

More recent frameworks have integrated these methods with novel scoring systems. For instance, one study designed a Co-Regulation Score (CRS) based on motif comparisons, which was reported to capture co-regulation relationships more effectively than traditional scores like Partial Correlation Score (PCS) or Gene Functional Relatedness (GFR) [1]. Evaluations against documented regulons in E. coli showed that such integrated approaches can make the regulon prediction problem "substantially more solvable and accurate" [1].

Bridging the Gap: The Imperative of Experimental Corroboration

The transition from computational prediction to biological insight necessitates experimental corroboration. This process does not "validate" the model itself, which is a logical construct, but tests the accuracy of its predictions and refines its parameters [8]. In the Big Data era, the necessity for this step is sometimes questioned, but it remains critical. The question is not whether to use experimental data, but how to use it most effectively—and which experimental methods provide the most reliable ground truth.

The Concept of Ground-Truthing

In machine learning, ground truth refers to the reality one wants to model, often represented by a labeled dataset used for training or validation [10]. In computational biology, ground-truthing involves using orthogonal experimental methods to provide a reliable benchmark against which predictions can be tested [11]. This is distinct from the concept of a permanent "gold standard," as technological progress can redefine what is considered the most reliable method [8].

Comparative Analysis of Experimental Corroboration Methods

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Methods for Corroborating Computational Predictions

| Computational Prediction | Traditional "Gold Standard" | Higher-Throughput/Resolution Orthogonal Method | Comparative Advantage of Orthogonal Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copy Number Aberration (CNA) Calling [8] | Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization (FISH) (~20-100 cells) [8] | Low-depth Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) of thousands of single cells [8] | Higher resolution for subclonal and small events; quantitative and less subjective [8]. |

| Mutation Calling (WGS/WES) [8] | Sanger dideoxy sequencing [8] | High-depth targeted sequencing [8] | Can detect variants with low variant allele frequency (<0.5); more precise VAF estimates [8]. |

| Differential Protein Expression [8] | Western Blot / ELISA [8] | Mass Spectrometry (MS) [8] | Higher detail, more data points, robust and reproducible; antibodies not always available or efficient [8]. |

| Differentially Expressed Genes [8] | Reverse Transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) [8] | Whole-Transcriptome RNA-seq [8] | Comprehensive, nucleotide-level resolution, enables discovery of new transcripts [8]. |

As illustrated, there is a paradigm shift where newer, high-throughput methods like RNA-seq and mass spectrometry are often more reliable and informative than older, low-throughput "gold standards" [8]. This reprioritization is crucial for effective ground-truthing; using an outdated or low-resolution experimental method to judge a sophisticated computational prediction can be misleading.

An Integrated Workflow for Regulon Prediction and Corroboration

The following diagram synthesizes the computational and experimental processes into a cohesive workflow for regulon research, highlighting the cyclical nature of prediction and corroboration.

Research Workflow for Regulon Prediction and Corroboration

Success in regulon research depends on a suite of computational and experimental resources. The table below details key reagents and their functions in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Regulon Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Regulon Research |

|---|---|---|

| RegulonDB [1] | Database | A curated database of documented regulons and operons in E. coli, used as a benchmark for evaluating computational predictions [1]. |

| DOOR2.0 Database [1] | Database | A resource containing complete and reliable operon predictions for over 2,000 bacterial genomes, providing high-quality input data for motif finding [1]. |

| AlignACE [9] | Software | A motif-discovery program used to identify potential regulatory motifs in the upstream regions of genes within a predicted regulon [9]. |

| DMINDA Web Server [1] | Software Platform | An online platform that implements integrated regulon prediction frameworks, allowing application to over 2,000 sequenced bacterial genomes [1]. |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq) [12] | Experimental Method | Discovers genome-wide binding sites for transcription factors or histone modifications, providing direct evidence of physical DNA-protein interactions for regulon components [12]. |

| Whole-Transcriptome RNA-seq [8] [12] | Experimental Method | Provides comprehensive, quantitative data on gene expression under different conditions, used to test predictions of coregulation within a regulon [8]. |

| Mass Spectrometry [8] [12] | Experimental Method | Enables robust and reproducible protein detection and quantification, allowing corroboration of predicted regulatory outcomes at the proteome level [8]. |

The critical gap between computational predictions and biological reality is best bridged by fostering a culture that values orthogonal corroboration over simple validation. Computational models are indispensable for navigating the complexity of big biological data and generating hypotheses [8]. However, their predictions must be tested through carefully designed experiments that often leverage modern, high-throughput methods for greater reliability. The interplay between computation and experiment is not a linear process of validation but a cyclical, reinforcing loop of prediction, calibration, and refinement. By adopting this framework and utilizing the comparative tools and reagents outlined in this guide, researchers can more reliably transform computational predictions of regulons and other biological features into validated biological knowledge.

In the study of transcriptional regulatory networks, a gold standard refers to a set of high-confidence direct transcriptional regulatory interactions (DTRIs) that serves as the best available benchmark for evaluating new predictions and experimental methods [13] [14]. Unlike theoretical concepts, practical gold standards in biology represent the most reliable knowledge available at a given time, acknowledging that they may be imperfect and subject to refinement as new evidence emerges [13] [15]. For regulon prediction research, gold standard datasets provide the essential foundation for training computational algorithms, benchmarking prediction accuracy, and validating novel regulatory interactions through experimental approaches [16] [1].

The establishment of gold standards has evolved significantly with advancements in both experimental technologies and curation frameworks. In molecular biology, the term "gold standard" does not imply perfection but rather the best available reference under reasonable conditions, often achieving a balance between accuracy and practical applicability [13] [14]. This is particularly relevant for regulon research, where our understanding of transcriptional networks continues to be refined through integrated approaches combining classical genetics, high-throughput technologies, and computational predictions [16]. As the field progresses, what constitutes a gold standard necessarily changes, with former standards being replaced by more accurate methods as evidence accumulates [13] [15].

Table: Evolution of Gold Standards in Transcriptional Regulation Research

| Era | Primary Methods | Key Characteristics | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical (Pre-genomic) | Gene expression analysis, binding of purified proteins, mutagenesis | Focus on individual regulators and targets; low-throughput but high-quality evidence | Lac operon regulation in E. coli [13] |

| Genomic | ChIP-chip, gSELEX, early computational predictions | Medium-throughput; beginning of genome-wide coverage | Initial regulon mapping in model organisms [16] [1] |

| Modern Multi-evidence | ChIP-seq, ChIP-exo, DAP-seq, integrated curation frameworks | High-throughput with quality assessment; evidence codes; confidence levels | RegulonDB with strong/confirmed confidence levels [16] |

Types and Applications of Gold Standards in Regulon Validation

Established Reference Databases as Gold Standards

Several curated databases serve as gold standards for regulon prediction validation by providing collections of literature-curated DTRIs. These resources undergo extensive manual curation from scientific literature and implement quality assessment measures to assign confidence levels to documented interactions.

RegulonDB represents a comprehensive gold standard for Escherichia coli K-12 transcriptional regulation, containing experimentally validated DTRIs with detailed evidence codes [16]. The database employs a sophisticated confidence classification system categorizing interactions as "weak," "strong," or "confirmed" based on the quality and multiplicity of supporting evidence [16]. This tiered approach allows researchers to select appropriate stringency thresholds for validation purposes. The architecture of evidence in RegulonDB distinguishes between experimental methods (both classical and high-throughput) and computational predictions, enabling transparent assessment of the underlying support for each documented interaction [16].

TRRUST (Transcriptional Regulatory Relationships Unravelled by Sentence-based Text-mining) provides a gold standard for human TF-target interactions, currently containing 8,015 interactions between 748 TF genes and 1,975 non-TF genes [17]. This database employs sentence-based text-mining of approximately 20 million Medline abstracts followed by manual curation, with about 60% of interactions including mode-of-regulation annotations (activation or repression) [17]. TRRUST offers unique features for network analysis, including tests for target modularity of query TFs and assessments of TF cooperativity for query targets, facilitating systems-level validation of regulon predictions [17].

Flexible and Composite Gold Standards

In recognition that single-method gold standards may be imperfect, researchers have developed more flexible approaches that incorporate multiple evidence types. The concept of flexible gold standards allows selective inclusion or exclusion of specific evidence types to avoid circularity when benchmarking new methods [16]. For example, in RegulonDB, users can exclude the specific high-throughput method they wish to benchmark while retaining other independent evidence types, enabling fair evaluation of novel approaches [16].

Composite reference standards represent another approach for complex biological phenomena, combining multiple tests or criteria in a hierarchical system [18]. This method is particularly valuable when no single test provides definitive evidence, as is often the case with transcriptional regulation where binding evidence must be complemented with functional validation. Composite standards can incorporate diverse evidence types including protein-DNA binding, gene expression changes, chromatin conformation data, and functional assays, with weighted significance according to the strength of evidence [18].

Table: Evidence Types Supporting Gold Standard DTRIs

| Evidence Category | Specific Methods | Typical Application in Gold Standards | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Molecular Biology | Binding of purified proteins, gene expression analysis, mutagenesis | Foundational evidence for reference databases | High reliability per interaction; functional validation | Low throughput; limited to well-studied systems |

| High-Throughput Binding | ChIP-seq, ChIP-exo, DAP-seq, gSELEX | Genome-wide binding evidence | Comprehensive coverage; precise mapping | Functional consequences often inferred |

| Functional Genomics | RNA-seq after TF perturbation, CRISPR screens | Validation of regulatory consequences | Direct evidence of transcriptional effects | Indirect evidence of binding; secondary effects |

| Computational Predictions | Motif discovery, phylogenetic footprinting | Supporting evidence when experimentally validated | Can identify novel relationships | Requires experimental validation |

| Literature Curation | Text-mining followed by manual curation | Integration of dispersed knowledge | Contextual information; mode of regulation | Incomplete coverage; potential for interpretation bias |

Experimental Protocols for Gold Standard Development

High-Throughput TF Binding Mapping

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) provides genome-wide mapping of transcription factor binding sites. The protocol begins with cross-linking proteins to DNA in living cells using formaldehyde, followed by chromatin fragmentation through sonication. Immunoprecipitation with TF-specific antibodies enriches DNA fragments bound by the TF, after which cross-links are reversed and the immunoprecipitated DNA is purified. Library preparation and high-throughput sequencing identify genomic regions bound by the TF, with bioinformatic analysis pinpointing precise binding locations [16].

DNA Affinity Purification sequencing (DAP-seq) offers an alternative method that identifies TF binding sites in vitro without cell culture. Genomic DNA is extracted, fragmented, and adapter-ligated to create an input library. Recombinant TFs are incubated with the DNA library, allowing formation of protein-DNA complexes. TF-bound DNA fragments are isolated, amplified, and sequenced, revealing genome-wide binding specificities without requiring TF-specific antibodies [16].

Validation of Regulatory Interactions

Gene expression analysis in TF perturbation experiments provides functional validation of regulatory interactions. This involves creating TF knockout or overexpression strains and comparing transcriptomes to wild-type controls using RNA sequencing. Significantly differentially expressed genes are considered potential regulatory targets, with direct targets distinguished through integration with binding data [19].

Reporter gene assays test the regulatory function of specific DNA elements. Putative regulatory regions are cloned upstream of a reporter gene (e.g., GFP, luciferase), and the construct is introduced into host cells. Reporter activity is measured under conditions of TF presence versus absence (e.g., in ΔsigB mutants), confirming both interaction and regulatory effect [19].

Visualization of Gold Standard Development Workflows

Experimental Validation Workflow for DTRIs

Confidence Assignment Architecture for Gold Standards

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DTRI Validation

| Category | Specific Reagents/Resources | Function in Gold Standard Development | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | TF-specific immunoprecipitation-grade antibodies | Enrichment of TF-bound DNA fragments in ChIP experiments | ChIP-seq for genome-wide binding mapping [16] |

| Library Preparation Kits | ChIP-seq, DAP-seq, RNA-seq library preparation kits | Preparation of sequencing libraries from limited input material | High-throughput binding and expression profiling [16] |

| Reporter Systems | Fluorescent proteins (GFP, RFP), luciferase reporters | Functional validation of regulatory elements | Testing putative promoter activity [19] |

| Strain Collections | TF knockout mutants, overexpression strains | Determination of TF necessity/sufficiency for regulation | Expression analysis in perturbation backgrounds [19] |

| Reference Databases | RegulonDB, TRRUST, REDfly | Benchmarking and validation of novel predictions | Gold standard comparisons for new regulon maps [16] [17] |

| Motif Discovery Tools | MEME Suite, HOMER | Identification of conserved regulatory motifs | De novo motif finding in co-regulated genes [19] [1] |

| Curated Motif Databases | JASPAR, TRANSFAC | Reference TF binding specificity models | Comparison with discovered motifs [1] |

The establishment of high-confidence gold standards for direct transcriptional regulatory interactions remains fundamental to advancing our understanding of gene regulatory networks. The evolution from single-method benchmarks to integrated, multi-evidence frameworks represents significant progress in the field [16] [15]. These refined approaches acknowledge the complexity of transcriptional regulation while providing practical benchmarks for validating regulon predictions.

Future developments in gold standard curation will likely incorporate additional dimensions of evidence, including single-cell resolutiοn data, spatial transcriptomics, and multi-omics integration. As these standards evolve, maintaining transparent curation practices, clear evidence classification, and accessibility to the research community will be essential for maximizing their utility in driving discoveries in transcriptional regulation and its applications in basic research and therapeutic development.

The accurate prediction of gene regulatory networks (GRNs) and the transcription factor (TF) regulons within them is a fundamental goal in systems biology. However, these computational predictions require rigorous experimental validation to confirm their biological relevance. This guide objectively compares the primary experimental methodologies used for this validation: TF perturbation assays, TF-DNA binding measurements, and TF-reporter assays. Each approach provides a distinct and complementary line of evidence, and the choice of method depends on the specific research question, ranging from the direct physical detection of binding events to the functional assessment of TF activity within a cellular context. We synthesize current experimental data and protocols to provide a clear comparison of these techniques, framed within the broader thesis of validating regulon predictions.

Methodological Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, applications, and key performance metrics of the three major methodological categories.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Experimental Methods for TF and Regulon Validation

| Method Category | Key Methods | Primary Application in Regulon Validation | Throughput | Key Measured Output | Critical Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TF Perturbation | CRISPR Knock-out, RNAi [20] [21] | Establish causal links between a TF and its predicted target genes. | Medium | Gene expression changes (e.g., from RNA-seq) in perturbed vs. wild-type cells. | Distinguishing direct from indirect effects is challenging. |

| TF-DNA Binding | ChIP-seq [20] [22], EMSA [22] [23], PBMs [24] [22], HiP-FA [24] | Directly measure physical interaction between a TF and specific DNA sequences. | Low (EMSA) to High (PBM, ChIP-seq) | Binding sites, affinity (KD), kinetics (kon, koff). | In vitro methods (EMSA, PBM) may not reflect in vivo chromatin context. |

| TF-Reporter Assays | Luciferase, GFP [25], Multiplexed Prime TF Assay [26] [27] | Functionally test the transcriptional activation capacity of a DNA sequence by a TF. | Low (single) to High (multiplexed) | Reporter gene activity (luminescence, fluorescence). | Reporter construct design and genomic integration site can significantly influence results. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Data

TF Perturbation Assays

Perturbation assays establish causal relationships by observing transcriptomic changes after experimentally altering TF function.

- Perturbation-based Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRAs): This powerful hybrid approach combines perturbation with high-throughput reporter sequencing. As detailed in [20], researchers selected 591 temporally active regulatory sequences and perturbed 2,144 instances of DNA-binding motifs within them during neural differentiation. The protocol involved:

- Library Design: Synthesizing a library of regulatory sequences with wild-type and perturbed motif sequences cloned upstream of a transcribed barcode.

- Lentiviral Delivery: Using lentiMPRA to integrate the library into the genome of neural stem cells, ensuring one copy per cell.

- Temporal Monitoring: Collecting samples at seven early time points (0–72 h) during differentiation.

- Sequencing & Analysis: Quantifying reporter activity via barcode sequencing (RNA-seq) and comparing it to the abundance of the coding sequence (DNA-seq) to calculate the effect of each motif perturbation on transcriptional output.

- CRISPR/RNAi Knock-out Validation: A study evaluating computational TF activity inference methods used TF knock-out (TFKO) datasets as a gold standard for validation [21]. In these experiments, a specific TF is knocked out in a cell line (e.g., yeast or cancer cell lines), and the subsequent RNA-seq data is analyzed. A successful regulon prediction is validated if the known target genes of the knocked-out TF show significant differential expression, confirming the TF's direct regulatory role.

TF-DNA Binding Assays

These assays quantify the physical interaction between a TF and DNA, providing the foundational evidence for direct binding.

- High-Performance Fluorescence Anisotropy (HiP-FA): This in vitro solution-based method measures binding affinities with high sensitivity [24]. A key study used HiP-FA to characterize zeroth- (PWM) and first-order (dinucleotide) binding specificities for 13 Drosophila TFs.

- Protocol: The TF is titrated against a fluorescently-labeled DNA probe containing the binding site.

- Measurement: As the TF binds the probe, the rotational speed of the complex slows, increasing the fluorescence anisotropy.

- Data Output: The data is fitted to a binding curve to extract the dissociation constant (KD), providing a quantitative measure of binding affinity. This method was instrumental in demonstrating the widespread use of DNA shape readout by TFs [24].

- Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA): A classic, low-tech method for detecting protein-DNA interactions [22] [23].

- Protocol: A purified TF is incubated with a labeled DNA probe. The mixture is run on a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel.

- Measurement: Protein-DNA complexes migrate more slowly than free DNA, resulting in a "shifted" band.

- Data Output: A qualitative or semi-quantitative confirmation of binding. It does not provide kinetic constants and is low-throughput [23].

- Protein Binding Microarrays (PBMs): A high-throughput in vitro method that assesses binding to thousands of synthesized DNA sequences on a microarray [22]. This allows for the de novo identification of binding motifs and relative affinities.

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for using in vitro binding assays to characterize TF specificity, as applied in studies like the HiP-FA research on Drosophila TFs [24].

TF-Reporter Assays

Reporter assays test the functional consequence of TF binding—transcriptional activation.

- Multiplexed "Prime" TF Reporter Assay: This optimized method enables the simultaneous measurement of up to 100 TF activities in a single experiment [26] [27].

- Protocol Summary [27]:

- Library Transfection: A barcoded plasmid library of optimized TF-responsive reporters (the "prime" library) is transfected into cultured cells.

- RNA Processing & Sequencing: After treatment or differentiation, RNA is extracted, and the reporter barcodes are reverse-transcribed and sequenced.

- Computational Analysis: The computational pipeline

primetimequantifies TF activity by comparing barcode counts from RNA to those from the plasmid library, identifying TFs with differential activity across conditions.

- Performance: This systematic design and optimization of reporters for 86 TFs resulted in a collection of 62 "prime" reporters with enhanced sensitivity and specificity, many outperforming previously available reporters [26].

- Protocol Summary [27]:

- Classical In Vitro Androgen Reporter Assays: These are used in toxicology and drug discovery to identify endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) [25].

- Protocol: A cell line (e.g., CHO, MCF-7) is stably transfected with an androgen receptor (AR) expression plasmid and a reporter plasmid (e.g., luciferase) under the control of an androgen-responsive element.

- Measurement: Cells are exposed to test compounds. Androgenic or antiandrogenic activity is quantified by measuring increases or decreases in luciferase activity, respectively, relative to controls.

The workflow for a multiplexed TF reporter assay, as described in the 2025 protocol, is visualized below [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Successful execution of these experiments relies on critical reagents and tools, as highlighted in the search results.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Key Features & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmid Reporter Libraries | High-throughput functional screening of TF activity. | Prime TF Library (pMT52): A collection of 62 optimized, highly specific reporters for multiplexed activity detection [26] [27]. |

| Cell Lines | Provide the cellular context for reporter, binding, and perturbation assays. | U2OS, HEK293, K562, mESCs: Commonly used, well-characterized lines. Selection depends on pathway activity and transfection efficiency [27]. |

| Competent Cells | Amplification of complex plasmid libraries while preserving diversity. | MegaX DH10B T1 R Electrocomp Cells: High transformation efficiency for stable propagation of complex libraries [27]. |

| Consensus Regulon Databases | Provide prior knowledge of TF-target gene interactions for computational validation and network analysis. | DoRothEA, Pathway Commons: Curated databases of TF-gene interactions used by tools like VIPER and TIGER to infer TF activity from RNA-seq data [28] [21]. |

| Antistaphylococcal agent 3 | Antistaphylococcal agent 3, MF:C25H19N5O3, MW:437.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| LeuRS-IN-1 | LeuRS-IN-1, MF:C10H13BClNO3, MW:241.48 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrated Validation Strategy

No single method is sufficient for comprehensive regulon validation. An integrated strategy is paramount. For instance, a predicted regulon for a neural TF can be validated by:

- Binding Evidence: Confirming in vivo binding to promoter/enhancer regions of target genes via ChIP-seq [20] [22].

- Functional Evidence: Demonstrating that perturbation of the binding motif in an MPRA or reporter construct ablates transcriptional activity [20].

- Perturbation Evidence: Showing that CRISPR-mediated knock-down of the TF alters the expression of the predicted target genes [21].

- Computational Correlation: Inferring TF activity from bulk or single-cell RNA-seq using tools like TIGER [21] or Priori [28] and confirming that the activity score correlates with the expression of the predicted regulon and the experimental condition.

This multi-faceted approach, combining computational prediction with experimental evidence from binding, perturbation, and functional assays, provides the most robust framework for validating transcription factor regulons and illuminating the architecture of gene regulatory networks.

This guide provides an objective comparison of computational methods for predicting cell-type-specific regulons and their dynamics, benchmarking their performance against experimental validation data. The increasing availability of single-cell multi-omics data has fueled the development of sophisticated algorithms that reverse-engineer gene regulatory networks (GRNs) and splicing-regulatory networks across diverse cellular contexts. Below, we summarize key computational methods and their performance characteristics based on recent benchmarking studies.

Table 1: Key Computational Methods for Regulon and Network Inference

| Method Name | Primary Function | Data Inputs | Key Strengths | Experimental Validation Cited |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scMTNI [29] | Infers GRNs on cell lineages | scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, cell lineage structure | Accurately infers GRN dynamics; identifies key fate regulators [29] | Mouse cellular reprogramming; human hematopoietic differentiation [29] |

| MR-AS [30] [31] | Reverse-engineers splicing-regulatory networks | scRNA-seq (pseudobulk) | Infers RBP regulons and cell-type-specific activity [30] | In vitro ESC differentiation; Elavl2 role in interneuron splicing [30] |

| GGRN/PEREGGRN [32] | Benchmarks expression forecasting methods | Perturbation transcriptomics datasets | Modular software for neutral evaluation of diverse methods [32] | Benchmarking on 11 large-scale perturbation datasets [32] |

| Normalisr [33] | Normalization & association testing for scRNA-seq | scRNA-seq, CRISPR screen data | Unified framework for DE, co-expression, and CRISPR analysis; high speed [33] | K562 Perturb-seq data; synthetic null datasets [33] |

| ARACNe/VIPER [30] | Infers regulons and master regulator activity | Transcriptomic data | Information-theoretic network inference; estimates protein activity [30] | Validation against integrative splicing models and RBP perturbations [30] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: Single-Cell CRISPRi Screening for Regulon Validation

This protocol, adapted from Genga et al., details how to functionally test predicted transcription factors (TFs) during definitive endoderm (END) differentiation [34].

- Key Reagents:

- Cell Line: H1-AAVS1-TetOn-dCas9-KRAB human embryonic stem cells (ESCs).

- Perturbation: Lentiviral guide RNA (gRNA) library targeting candidate TFs.

- Procedure:

- Differentiation: Initiate differentiation of ESCs to definitive endoderm.

- Perturbation: Transduce cells with the gRNA library.

- Single-Cell Sequencing: At the END time point, harvest cells and perform droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to capture transcriptomes and gRNA identities simultaneously.

- Cluster Analysis: Perform unsupervised clustering (e.g., t-SNE) on the scRNA-seq data.

- Identify Phenotypes: Identify clusters with aberrant transcriptomic states (e.g., blocks in differentiation) by assessing expression of END markers (SOX17, FOXA2, CXCR4) and pluripotency markers (POU5F1, NANOG).

- Validate Regulators: Statistically test for enrichment of specific gRNAs in aberrant clusters. For example, gRNAs targeting TGFβ pathway factors (FOXH1, SMAD2, SMAD4) were significantly enriched in non-END clusters, validating their predicted role [34].

- Data Analysis: The differentiation blockade is quantified by comparing the gene expression profile of each cluster to a bulk RNA-seq time course of control END differentiation [34].

Protocol: Validating Splicing-Regulatory Networks In Vitro

This protocol, from Moakley et al., describes the validation of a predicted RBP, Elavl2, in mediating neuron-type-specific alternative splicing [30].

- Key Reagents:

- Cell Line: Embryonic stem cells (ESCs).

- Target: Elavl2, a predicted key RBP for medial ganglionic eminence (MGE)-lineage interneurons.

- Procedure:

- Network Inference: Use the MR-AS pipeline (based on ARACNe/VIPER) on pseudobulk scRNA-seq data from 133 mouse neocortical cell types to infer RBP regulons and activity [30].

- In Vitro Differentiation: Differentiate wild-type and Elavl2-perturbed (knockdown or knockout) ESCs into MGE-lineage interneurons.

- Splicing Analysis: Quantify alternative splicing (e.g., using RNA-seq) in the resulting neuronal cells.

- Validation: Compare the observed splicing changes in the Elavl2-perturbed cells to the targets and mode of regulation (MOR) predicted by the computational network. A significant concordance validates the network prediction [30].

- Data Analysis: Splicing changes are quantified, and the overlap and concordance in the direction of regulation between the predicted Elavl2 regulon and the experimentally observed differentially included exons are statistically assessed [30].

Visualization of Workflows

Diagram: Regulon Prediction and Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental pipeline for deriving and validating cell-type-specific regulons.

Diagram: Single-Cell CRISPRi Screening Process

This diagram outlines the key steps in a single-cell CRISPRi screen used to validate predicted regulon components.

Performance Benchmarking Data

Independent benchmarking studies provide crucial quantitative data on the performance of various computational methods.

Table 2: Benchmarking Performance of GRN Inference Methods Data derived from a simulation study comparing multi-task and single-task learning algorithms on synthetic single-cell expression data with known ground truth networks. Performance was measured by Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) and F-score of the top k edges (where k is the number of edges in the true network) [29].

| Method | Type | Performance (AUPR) | Performance (F-score) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scMTNI | Multi-task | High | High | Accurately recovers network structure; benefits from lineage prior [29]. |

| MRTLE | Multi-task | High | High | Top performer, comparable to scMTNI in some tests [29]. |

| AMuSR | Multi-task | High | Low | High AUPR but inferred networks are overly sparse, leading to low F-score [29]. |

| Ontogenet | Multi-task | Moderate | Moderate | Better than single-task methods in some cell types [29]. |

| SCENIC | Single-task | Low | Moderate | Uses non-linear regression model [29]. |

| LASSO | Single-task | Low | Low | Standard linear model baseline [29]. |

Table 3: GGRN Benchmarking on Real Perturbation Data The PEREGGRN platform benchmarked various expression forecasting methods across 11 perturbation datasets. A key finding was that it is uncommon for methods to outperform simple baselines, highlighting the challenge of accurate prediction [32].

| Prediction Method / Baseline | Performance Relative to Baseline | Context / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Various GRN-based methods | Often failed to outperform | Across 11 diverse perturbation datasets [32]. |

| "Mean predictor" baseline | Frequently unoutperformed | Predicts no change from the average expression [32]. |

| "Median predictor" baseline | Frequently unoutperformed | Predicts no change from the median expression [32]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Regulon Research and Validation

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Regulon Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9-KRAB Cell Line | Enables CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for targeted gene repression in a pooled format. | Validating the role of specific TFs (e.g., SMAD2, FOXH1) in cell fate decisions during differentiation [34]. |

| Lentiviral gRNA Libraries | Delivers guide RNAs for scalable, parallel perturbation of multiple candidate regulator genes. | High-throughput functional screening of TFs predicted by chromatin accessibility (e.g., atacTFAP) [34]. |

| scRNA-seq Kits (10x Genomics) | Captures transcriptome-wide gene expression and gRNA identity in single cells. | Identifying transcriptomic states and gRNA enrichments in CRISPRi screens [34] [33]. |

| scATAC-seq Kits | Profiles genome-wide chromatin accessibility in single cells. | Generating cell-type-specific priors on TF-target interactions for GRN inference methods like scMTNI [29]. |

| Stem Cell Differentiation Kits | Provides a controlled system for in vitro differentiation into specific lineages. | Validating the function of predicted regulators (e.g., Elavl2) in specific neuronal subtypes [30]. |

| ARACNe/VIPER Algorithm | Infers regulons and estimates master regulator activity from transcriptomic data. | Reverse-engineering splicing-regulatory networks (MR-AS) from scRNA-seq data of diverse cell types [30]. |

| Cobomarsen | Cobomarsen, CAS:1848257-52-2, MF:C148H177N52O77P13S13, MW:4736 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Antibacterial agent 50 | Antibacterial agent 50, MF:C13H18N5NaO9S, MW:443.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Computational Tools and Experimental Pipelines for Regulon Inference and Confirmation

Gene regulatory networks (GRNs) represent the complex circuits of interactions where transcription factors (TFs) and transcriptional coregulators control target gene expression, ultimately shaping cell identity and function [6]. The accurate inference of these networks from genomic data is fundamental to understanding developmental biology, cellular differentiation, and disease mechanisms such as cancer. However, a significant challenge in GRN inference lies in the fact that TF activity is often decoupled from its mRNA expression due to post-transcriptional regulation, post-translational modifications, and the effects of pharmacological interventions [6]. Traditional methods that rely solely on gene expression data often fail to capture these important regulatory dynamics, limiting their biological accuracy and utility in drug discovery.

The emergence of single-cell multiomics technologies, which enable joint profiling of chromatin accessibility (scATAC-seq) and gene expression (scRNA-seq) in the same cell, provides unprecedented opportunities to overcome these limitations. In this comparative guide, we evaluate Epiregulon, a recently developed GRN inference method that specifically addresses the challenge of predicting TF activity decoupled from expression, and contrast it with other established tools in the field. Through experimental validation and benchmarking, we demonstrate how Epiregulon advances the field of regulon prediction and its application in therapeutic development.

Core Algorithm and Innovative Approach

Epiregulon constructs GRNs from single-cell multiomics data by leveraging the co-occurrence of TF expression and chromatin accessibility at TF binding sites in individual cells [6]. Unlike methods that assume linear relationships between TF expression and target genes, Epiregulon employs a distinctive weighting scheme based on statistical testing of cellular subpopulations, making it particularly suited for scenarios where TF activity is not directly reflected in mRNA levels.

The methodological workflow proceeds through several key stages:

- Identification of Regulatory Elements (REs): Epiregulon first identifies REs from regions of open chromatin in scATAC-seq data [6].

- Filtering by TF Binding Sites: These REs are then filtered to retain only those overlapping with binding sites of the TF of interest, typically determined from external ChIP-seq data [6]. The method provides a pre-compiled resource from ENCODE and ChIP-Atlas encompassing 1,377 factors across 828 cell types/lines and 20 tissues [6].

- Target Gene Assignment and Weighting: Each RE is tentatively linked to genes within a specified genomic distance. A gene is considered a bona fide target if a strong correlation exists between ATAC-seq and RNA-seq counts across metacells. Critically, each RE-target gene (TG) edge is assigned a weight using the "co-occurrence method" – defined as the Wilcoxon test statistic comparing TG expression in "active" cells (which both express the TF and have open chromatin at the RE) against all other cells [6].

- GRN Construction and Activity Inference: The process yields a weighted tripartite graph connecting TFs, REs, and TGs. The activity of a TF in a given cell is then calculated as the RE-TG-edge-weighted sum of its target genes' expression values, normalized by the number of targets [6].

Epiregulon's Unique Capacity for Motif-Agnostic Inference

A distinctive capability of Epiregulon is its motif-agnostic inference of transcriptional coregulators and TFs with neomorphic mutations by leveraging ChIP-seq data [6]. Most GRN methods rely on sequence-specific motifs to connect TFs to their target genes, which precludes the analysis of important transcriptional coregulators that lack defined DNA-binding motifs but interact with DNA-bound TFs in a context-specific manner. By directly incorporating TF binding sites from ChIP-seq, Epiregulon overcomes this limitation and expands the scope of analyzable regulatory proteins.

Comparative Benchmarking: Epiregulon Versus Alternative Methods

Performance Evaluation on PBMC Data

To objectively evaluate Epiregulon's performance, we compare it against other GRN inference methods, including SCENIC+, CellOracle, Pando, FigR, and GRaNIE, using a human peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) dataset [6] [35].

Table 1: Benchmarking of GRN Methods on PBMC Data

| Method | Recall of True Target Genes | Precision | Computational Time | Memory Usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epiregulon | Highest | Moderate | Lowest | Lowest |

| SCENIC+ | Moderate | Highest | High | High |

| CellOracle | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Pando | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| FigR | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| GRaNIE | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

When evaluated using knockTF data from 7 factors depleted in human blood cells (ELK1, GATA3, JUN, NFATC3, NFKB1, STAT3, and MAF), Epiregulon demonstrated superior recall in detecting genes with altered expression upon TF depletion, though with a modest trade-off in precision compared to SCENIC+ [6]. This indicates that Epiregulon is particularly well-suited for applications where comprehensive recovery of potential target genes is prioritized.

Notably, Epiregulon achieved this performance with the lowest computational time and memory requirements among the benchmarked methods [6], making it advantageous for large-scale or iterative analyses.

Comparison to SCENIC+ and Other Multiomic Methods

SCENIC+, another advanced method for inferring enhancer-driven GRNs, utilizes a different three-step workflow: identifying candidate enhancers, detecting enriched TF-binding motifs using a large curated collection of over 30,000 motifs, and linking TFs to enhancers and target genes [35]. While SCENIC+ has demonstrated high precision and excellent recovery of cell-type-specific TFs in ENCODE cell line data [35], its dependency on motif information limits its ability to infer regulators without defined motifs.

Table 2: Feature Comparison Between Epiregulon and SCENIC+

| Feature | Epiregulon | SCENIC+ |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Input | scATAC-seq + scRNA-seq | scATAC-seq + scRNA-seq |

| TF-TG Linking Approach | Co-occurrence of TF expression & chromatin accessibility | GRNBoost2 + motif enrichment |

| Coregulator Inference | Yes (via ChIP-seq) | Limited (motif-dependent) |

| Activity-Decoupled Scenarios | Excellent handling | Limited handling |

| Motif Collection | Standard | Extensive (30,000+ motifs) |

| Computational Efficiency | High | Moderate to High |

| Experimental Validation | Drug perturbation responses | Cell state transitions, TF perturbations |

Other multi-task learning approaches, such as scMTNI (single-cell Multi-Task Network Inference), focus on integrating cell lineage structure with multiomics data to infer dynamic GRNs across developmental trajectories [29]. While scMTNI excels at modeling network dynamics on lineages, it has different design objectives compared to Epiregulon's focus on activity-expression decoupling.

Experimental Validation: Assessing Predictive Accuracy in Drug Response

Protocol for Validating AR-Modulating Drug Predictions

A key strength of Epiregulon lies in its ability to accurately predict cellular responses to pharmacological perturbations that disrupt TF function without directly affecting mRNA levels. To validate this capability, researchers designed an experiment using prostate cancer cell lines treated with different androgen receptor (AR)-targeting agents [6].

Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Line Selection: Six prostate cancer cell lines (4 AR-dependent and 2 AR-independent) were selected to represent different AR signaling contexts [6].

- Drug Treatments: Cells were treated with three different AR-modulating agents:

- Enzalutamide: A clinically approved AR antagonist that blocks the ligand-binding domain [6].

- ARV-110: An AR degrader that promotes ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of AR protein [6].

- SMARCA2_4.1: A degrader of SMARCA2 and SMARCA4, the ATPase subunits of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeler crucial for AR chromatin recruitment [6].

- Data Collection: Single-cell multiomics data (scRNA-seq + scATAC-seq) were collected following drug treatment. Cell viability was measured using CellTiter-Glo at 1 and 5 days post-treatment [6].

- Analysis: Epiregulon was applied to infer AR activity from the multiomics data, and predictions were correlated with measured viability outcomes.

Results and Validation of Predictions

The experimental results confirmed Epiregulon's predictive accuracy. Despite minimal cell death at 1 day post-treatment, Epiregulon successfully predicted subsequent viability effects based on inferred AR activity changes [6]. The method accurately captured the effects of different drug mechanisms - antagonist versus degrader - and identified context-dependent interaction partners of SMARCA4 in different cellular backgrounds [6].

This validation experiment demonstrates Epiregulon's particular utility in pharmaceutical research and drug discovery, where understanding the functional effects of targeted therapies on transcriptional regulators is essential.

Research Reagent Solutions for GRN Inference Studies

Implementing GRN inference methods like Epiregulon requires specific computational tools and data resources. The following table outlines key reagents and their applications in regulon prediction studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for GRN Inference

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application in GRN Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Single-cell Multiome Data (scATAC-seq + scRNA-seq) | Provides paired measurements of chromatin accessibility and gene expression in individual cells | Primary input for Epiregulon and other multiomic GRN methods [6] [35] |

| ChIP-seq Data | Identifies genome-wide binding sites for transcription factors | Enables motif-agnostic inference in Epiregulon; validation of predicted TF-binding regions [6] [36] |

| Pre-compiled TF Binding Sites (ENCODE, ChIP-Atlas) | Database of known transcription factor binding sites | Epiregulon provides pre-compiled resources spanning 1,377 factors for human studies [6] |

| knockTF Database | Repository of gene expression changes upon TF perturbation | Benchmarking and validation of predicted TF-target relationships [6] |

| Large Motif Collections (e.g., 30,000+ motifs in SCENIC+) | Libraries of TF binding motifs for enrichment analysis | Critical for motif-based methods like SCENIC+; improves TF identification recall and precision [35] |

| Lineage Tracing Data | Defines developmental relationships between cell states | Informs multi-task learning approaches like scMTNI for dynamic GRN inference [29] |

Signaling Pathways and Method Workflows

To visualize the core operational principles of Epiregulon and the experimental validation approach for drug response prediction, we present the following pathway diagrams.

Figure 1: Epiregulon Computational Workflow. The diagram illustrates the stepwise process of GRN construction and TF activity inference from single-cell multiomics data.

Figure 2: Experimental Validation Protocol for Drug Response Prediction. The workflow demonstrates how Epiregulon predictions are experimentally validated using AR-modulating compounds in prostate cancer models.

Epiregulon represents a significant advancement in GRN inference methodology, specifically addressing the critical challenge of predicting TF activity when it is decoupled from mRNA expression. Through its unique co-occurrence-based weighting scheme and ability to incorporate ChIP-seq data for motif-agnostic inference, Epiregulon expands the analytical toolbox available for studying transcriptional regulation.

The method's strong performance in recall, computational efficiency, and validated accuracy in predicting drug response makes it particularly valuable for both basic research and pharmaceutical applications. While methods like SCENIC+ offer exceptional motif resources and precision, and scMTNI excels at modeling lineage dynamics, Epiregulon fills a specific niche for scenarios involving post-transcriptional regulation, coregulator analysis, and pharmacological perturbation.

For researchers investigating transcriptional regulators as therapeutic targets, Epiregulon provides a robust framework for identifying key drivers of disease states and predicting the functional effects of targeted interventions. As single-cell multiomics technologies continue to evolve and become more widely adopted, methods like Epiregulon that fully leverage these rich datasets will play an increasingly important role in deciphering the complex regulatory logic underlying cellular identity and function.

Leveraging Foundation Models like GET for Cross-Cell-Type Regulatory Predictions

Gene regulatory networks (GRNs) control all biological processes by directing precise spatiotemporal gene expression patterns. A significant challenge in computational biology has been developing models that generalize beyond their training data to accurately predict gene expression and regulatory activity in unseen cell types and conditions [37]. Traditional models often lack generalizability, hindering their utility for understanding regulatory mechanisms across diverse cellular contexts, such as in disease states or developmental processes [37] [38].

Foundation models represent a transformative approach, leveraging extensive pretraining on broad datasets to develop a generalized understanding of transcriptional regulation [37] [39]. This guide objectively compares the performance of several foundation models, focusing on their experimental validation and applicability for cross-cell-type regulatory predictions in biomedical research.

Comparative Analysis of Foundation Models for Regulatory Prediction

Model Architectures and Core Approaches

Table 1: Key Foundation Models for Regulatory Prediction

| Model Name | Primary Architecture | Key Input Data | Interpretability Features | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GET (General Expression Transformer) | Interpretable transformer | Chromatin accessibility, DNA sequence | Attention mechanisms for regulatory grammars | Gene expression prediction, TF interaction networks [37] |

| scKGBERT | Knowledge-enhanced transformer | scRNA-seq, Protein-protein interactions | Gaussian attention for key genes | Cell annotation, Drug response, Disease prediction [39] |

| BOM (Bag-of-Motifs) | Gradient-boosted trees | TF motif counts from distal CREs | Direct motif contribution via SHAP values | Cell-type-specific CRE prediction [40] |

| Enformer | Hybrid convolutional-transformer | DNA sequence, Functional genomics data | Self-attention for long-range interactions | Gene expression prediction from sequence [37] |

Performance Metrics and Experimental Validation

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Models

| Model | Prediction Accuracy (Key Metric) | Cross-Cell-Type Generalization | Experimental Validation | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GET | Pearson r=0.94 in unseen astrocytes [37] | R²=0.53 in adult cells when trained on fetal data [37] | LentiMPRA (r=0.55), identifies leukemia mechanisms [37] | Superior to Enformer for regulatory elements [37] |

| BOM | auPR=0.99 for distal CRE classification [40] | auPR=0.85 across developmental stages [40] | Synthetic enhancers drive cell-type-specific expression [40] | Outperforms deep learning with fewer parameters [40] |

| scKGBERT | AUC=0.94 for dosage-sensitive TF prediction [39] | Strong cross-platform/disease generalizability [39] | Drug response prediction, oncogenic pathway activation [39] | Pre-trained on 41M single-cell transcriptomes [39] |

| Enformer | Moderate performance in comparative benchmarks [40] | Limited published data on unseen cell types | LentiMPRA (r=0.44) [37] | Computationally intensive for regulatory elements [37] |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

LentiMPRA Validation for Regulatory Activity Prediction

The lentivirus-based Massively Parallel Reporter Assay (lentiMPRA) provides a robust experimental framework for validating model predictions of regulatory elements in hard-to-transfect cell lines [37].

Protocol Details:

- Experimental Design: 226,243 sequences tested in K562 cell line with genomic integration to ensure relevant biological readouts [37]

- In Silico Simulation: GET model fine-tuned on bulk ENCODE K562 OmniATAC chromatin accessibility and NEAT-seq expression data [37]

- Prediction Method: Model infers activity of mini-promoters in corresponding chromatin context, averaging over all insertions for mean regulatory activity readout [37]

- Validation Metrics: Pearson correlation between predicted and experimental readouts, with GET achieving r=0.55 compared to Enformer's r=0.44 [37]

Chromatin Interaction-Based Validation with ICE-A

Interaction-based Cis-regulatory Element Annotator (ICE-A) enables cell type-specific identification of cis-regulatory elements by incorporating chromatin interaction data (e.g., Hi-C, HiChIP) into the annotation process [41].

Workflow Specifications:

- Input Data: 2D-bed (bedpe) files from interaction-calling software, peak files from ATAC-seq or ChIP-seq experiments [41]

- Annotation Modes: Basic (individual bed files), Multiple (co-occupancy analysis), Expression-integrated (association with gene expression changes) [41]

- Validation: Comparison with CRISPRi-FlowFISH data from functionally validated enhancer-gene pairs in K562 cells [41]

- Advantages: Overcomes limitations of proximity-based annotation restricted by local gene density and upper distance limits [41]

CausalBench Framework for Network Inference Validation

CausalBench provides a benchmark suite for evaluating network inference methods using real-world, large-scale single-cell perturbation data, addressing the challenge of ground-truth knowledge in GRN validation [38].

Experimental Framework:

- Datasets: Two large-scale perturbational single-cell RNA sequencing experiments (RPE1 and K562 cell lines) with over 200,000 interventional datapoints [38]

- Evaluation Metrics: Biology-driven approximation of ground truth and quantitative statistical evaluation using mean Wasserstein distance and false omission rate (FOR) [38]

- Key Finding: Methods using interventional information do not necessarily outperform observational methods, contrary to theoretical expectations [38]

- Performance Standouts: Mean Difference and Guanlab methods perform highly on both evaluations in the CausalBench challenge [38]

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Foundation Model Workflow for Cross-Cell-Type Regulatory Predictions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmarking Suites | CausalBench [38] | Provides biologically-motivated metrics and distribution-based interventional measures | Realistic evaluation of network inference methods |

| Annotation Tools | ICE-A (Interaction-based Cis-regulatory Element Annotator) [41] | Facilitates exploration of complex GRNs based on chromosome configuration data | Linking distal regulatory elements to target genes |

| Validation Databases | TRRUST database (8,427 TF-target interactions) [42] | Provides comprehensive information on human TF-target gene interactions | Ground truth for supervised learning approaches |

| Sequence Resources | GimmeMotifs database [40] | Clustered TF binding motifs that reduce redundancy | Motif annotation for sequence-based models like BOM |

| Perturbation Platforms | CRISPRi-based knockdown [38] | Enables causal inference through targeted gene perturbation | Validating predicted regulatory relationships |

Discussion and Future Directions

The emergence of foundation models represents a paradigm shift in computational biology, moving from cell type-specific predictions to generalizable models of transcriptional regulation. GET demonstrates exceptional accuracy (Pearson r=0.94) in predicting gene expression in completely unseen cell types, approaching experimental-level reproducibility between biological replicates [37]. Similarly, BOM achieves remarkable performance (auPR=0.99) in classifying cell-type-specific cis-regulatory elements using a minimalist bag-of-motifs representation [40].

A critical insight from comparative analysis is that model complexity does not necessarily correlate with predictive performance. BOM's gradient-boosted tree architecture outperforms more complex deep learning models like Enformer and DNABERT while using fewer parameters [40]. This emphasizes the importance of biologically-informed feature representation rather than purely increasing model complexity.

The integration of biological knowledge graphs, as demonstrated by scKGBERT, provides significant advantages for interpretability and functional insight. By incorporating 8.9 million regulatory relationships, scKGBERT enhances the biological relevance between gene and cell representations, facilitating more accurate learning of cellular and genomic features [39].

Future developments in foundation models for regulatory prediction will likely focus on improved integration of multi-omics data, enhanced interpretability for mechanistic insights, and expanded applicability across diverse biological contexts and species. The rigorous experimental validation frameworks discussed herein provide essential guidance for assessing model performance and biological relevance in real-world research scenarios.

Machine Learning and Hybrid Approaches for Enhanced GRN Prediction Accuracy

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) are fundamental to understanding the complex mechanisms that control biological processes, from cellular differentiation to disease progression. The accurate prediction of transcription factor (TF)-target gene interactions remains a central challenge in systems biology. While traditional statistical and machine learning (ML) methods have been widely used, recent advances in deep learning (DL) and hybrid models are setting new benchmarks for prediction accuracy. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these computational approaches, focusing on their performance in predicting regulons—sets of genes controlled by a single transcription factor. The validation of these predictions through experimental approaches forms a critical thesis in modern genomic research, offering invaluable insights for scientists and drug development professionals aiming to translate computational predictions into therapeutic targets.

Performance Comparison of GRN Inference Methods

The performance of GRN inference methods can be evaluated based on their accuracy, precision, recall, and their ability to handle specific challenges such as non-linear relationships and data scarcity. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and performance metrics of various approaches.

Table 1: Comparative performance of GRN inference methodologies

| Method Type | Examples | Reported Accuracy/Performance | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional ML & Statistical Models | GENIE3, TIGRESS, CLR, ARACNE [43] [44] | AUPR of 0.02–0.12 for real biological data [45] | Established benchmarks; good performance on synthetic data [46] | Struggles with high-dimensional, noisy data; may not capture non-linear relationships [43] |

| Deep Learning (DL) Models | CNN, LSTM, ResNet, DeepBind, DeeperBind [43] [47] | Outperformed GBLUP in 6 out of 9 traits in wheat and maize [47] | Excels at learning hierarchical, non-linear dependencies from raw data [43] [47] | Requires very large, high-quality datasets; can be prone to overfitting; "black box" nature [43] |

| Hybrid ML-DL Models | CNN-ML hybrids, CNN-LSTM, CNN-ResNet-LSTM [43] [48] [47] | Over 95% accuracy on holdout plant datasets; superior ranking of master regulators [43] [49] | Combines feature learning of DL with classification power of ML; handles complex data robustly [43] [48] | Performance depends on hyperparameter tuning and input data quality [48] |

| Supervised Learning Models | GRADIS, SIRENE [46] | Outperformed state-of-the-art unsupervised methods (AUROC & AUPR) [46] | Leverages known regulatory interactions to predict new ones; high accuracy [46] | Dependent on the quality and quantity of known positive instances for training [46] |

| Single-Cell Multiomics Methods | Epiregulon, SCENIC+, CellOracle [50] | High recall of target genes in PBMC data; infers TF activity decoupled from mRNA [50] | Integrates chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq) and gene expression; context-specific GRNs [50] | Precision can be modest; may require matched RNA-seq and ATAC-seq data [50] |