Evaluating Transcription Factor Binding Site Conservation: From Genomic Principles to Clinical Applications

This comprehensive review examines the principles, methods, and applications of transcription factor binding site (TFBS) conservation analysis across species.

Evaluating Transcription Factor Binding Site Conservation: From Genomic Principles to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines the principles, methods, and applications of transcription factor binding site (TFBS) conservation analysis across species. We explore how evolutionary conservation serves as a powerful filter for identifying functional regulatory elements amidst widespread non-functional binding. The article covers comparative genomics approaches, multi-species ChIP-seq strategies, and computational tools that leverage conservation to improve prediction accuracy. We critically evaluate different TF binding models, address common challenges like high false-positive rates, and demonstrate how conserved cis-regulatory modules control essential biological pathways. With specific examples from foundational research to recent breakthroughs in understanding the human gene regulatory code, this resource provides scientists and drug development professionals with practical frameworks for interpreting non-coding variation and prioritizing regulatory elements for experimental validation.

The Evolutionary Principles of TFBS Conservation: Why Conserved Binding Matters

The identification of conserved gene regulatory elements is fundamental to understanding the genetic basis of development, evolution, and disease. For decades, sequence conservation has been the primary tool for pinpointing functional non-coding DNA. However, emerging research reveals a more complex picture: many functional regulatory elements maintain their role across species despite significant sequence divergence. This comparison guide objectively examines the paradigms of sequence conservation and binding-site cluster conservation as strategies for identifying functional transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs). We present experimental data demonstrating that while sequence-based methods effectively identify deeply conserved elements, approaches focusing on the conservation of transcription factor binding-site clustering significantly enhance the discovery of functional cis-regulatory modules (CRMs), especially across larger evolutionary distances. This synthesis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a framework for selecting appropriate methodologies based on their specific evolutionary and functional questions.

The precise spatiotemporal regulation of gene expression is orchestrated by transcription factors (TFs) binding to specific DNA sequences known as transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs). These binding sites are often organized into functional clusters called cis-regulatory modules (CRMs) or enhancers [1] [2]. Identifying these functional elements across species is crucial for understanding evolutionary biology, developmental processes, and the regulatory basis of disease.

The concept of sequence conservation relies on the principle that functional DNA sequences, including regulatory elements, evolve more slowly than non-functional sequences due to purifying selection. This approach uses direct nucleotide sequence alignment to identify conserved regions, under the assumption that functional elements will exhibit higher sequence similarity than surrounding non-functional DNA [3] [4].

In contrast, the concept of binding-site cluster conservation posits that the functional unit of regulation is not the specific nucleotide sequence, but the spatial arrangement and combinatorial clustering of multiple TFBSs. This model suggests that the overall architecture of binding sites can be conserved even when individual binding sites undergo substantial sequence turnover [1] [4].

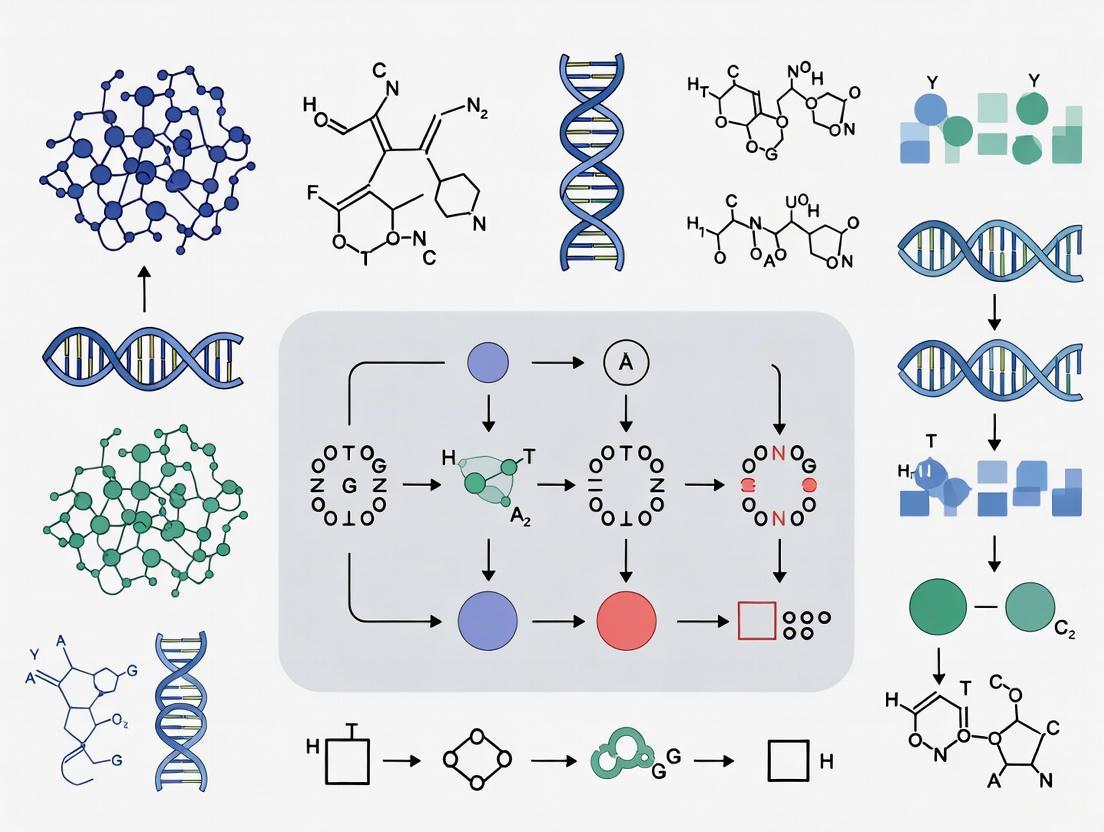

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between these two conservation paradigms and their functional outcomes:

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework for Identifying Conservation in Gene Regulation. Two primary paradigms—sequence conservation and binding-site cluster conservation—utilize different methodologies to identify functional cis-regulatory modules (CRMs), with varying effectiveness across evolutionary distances.

Comparative Analysis of Conservation Paradigms

Performance Across Evolutionary Distances

The utility of sequence-based versus cluster-based conservation methods varies significantly with evolutionary distance. The following table summarizes key comparative findings from empirical studies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison Across Evolutionary Distances

| Study System | Sequence Conservation Findings | Binding-Site Cluster Conservation Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drosophila species (D. melanogaster & D. pseudoobscura) | Limited ability to distinguish functional from non-functional binding-site clusters | Conservation of binding-site clustering accurately discriminated functional CRM | [1] |

| Mammalian liver (Human, macaque, mouse, rat, dog) | Only ~10% of enhancers showed sequence conservation | Two-thirds of TF-bound regions fell into CRMs; combinatorial analysis revealed conserved function | [3] |

| Mouse-Chicken heart development | Only 22% of promoters and 10% of enhancers were sequence-conserved | Synteny-based mapping identified 5x more conserved enhancers (42% total) | [4] |

| Insect A-P patterning (Drosophila & Tribolium) | Bicoid TFBS clusters found only in D. melanogaster | Hunchback, Knirps, Caudal, Kruppel TFBS clusters conserved despite sequence divergence | [2] |

Functional Validation and Predictive Power

The ultimate test of any conservation metric is its ability to predict functional regulatory elements. Both approaches have been rigorously validated through experimental approaches:

Table 2: Functional Validation Studies

| Conservation Approach | Experimental Validation Method | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding-site cluster conservation | Transgenic reporter assays in Drosophila embryos | 6 of 27 predicted clusters functioned as enhancers for adjacent genes; 3 drove expression unrelated to neighbors | [1] |

| Multi-species combinatorial binding | ChIP-seq for 4 liver TFs across 5 mammalian species | Shared CRMs associated with liver pathways and disease loci from GWAS | [3] |

| Synteny-based conservation | In vivo reporter assays in mouse for chicken enhancers | Functionally conserved enhancer activity despite sequence divergence | [4] |

| In silico TFBS cluster prediction | MCAST analysis of A-P patterning genes | TFBS cluster size <1kb in both species; more transversional than transitional sites | [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Identifying Binding-Site Cluster Conservation

The computational identification of conserved binding-site clusters involves multiple bioinformatics steps:

MCAST Analysis for TFBS Clusters: The Motif Cluster Alignment Search Tool (MCAST) scans genomic sequences for statistically significant clusters of non-overlapping transcription factor binding sites [2]. The protocol involves:

- Sequence Preparation: Extract genomic sequences including gene regions with 20kb upstream and downstream flanking regions

- Motif Collection: Obtain Position Weight Matrices (PWMs) for relevant transcription factors from databases like JASPAR

- Cluster Scanning: Run MCAST with stringent parameters (p-value < 0.005, gap between TFBS < 30bp)

- Orthologous Comparison: Identify and compare clusters across species

- Functional Annotation: Map clusters to promoter, exon, and intron regions using resources like Ensemble and NCBI

Synteny-Based Ortholog Identification: The Interspecies Point Projection (IPP) algorithm identifies orthologous regulatory elements independent of sequence similarity [4]:

- Anchor Point Identification: Define alignable genomic regions between species

- Bridged Alignment: Use multiple bridging species to increase anchor points

- Position Projection: Interpolate positions of non-alignable elements relative to anchors

- Confidence Classification: Categorize projections as Directly Conserved (DC), Indirectly Conserved (IC), or Nonconserved (NC) based on distance to anchors

Experimental Validation Workflows

Functional validation of predicted conserved elements requires rigorous experimental approaches:

In Vivo Reporter Assays: This gold-standard approach tests the enhancer activity of predicted regions:

- Element Cloning: Amplify candidate regulatory regions from genomic DNA

- Reporter Constructs: Clone elements upstream of minimal promoter and reporter gene (e.g., lacZ, GFP)

- Transgenesis: Generate transgenic organisms (flies, mice) carrying reporter constructs

- Expression Analysis: Assay embryos or tissues for reporter gene expression patterns

- Comparative Analysis: Compare expression patterns to native gene expression and across species

Multi-Species ChIP-Seq: This approach directly maps transcription factor binding events across species:

- Tissue Collection: Obtain homologous tissues from multiple species at equivalent developmental stages

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation: Use validated antibodies against conserved TF epitopes

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Process samples consistently across species

- Peak Calling: Identify significantly enriched binding regions in each species

- Orthology Mapping: Determine shared and species-specific binding events using alignment and synteny-based methods

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key experimental and computational steps for identifying and validating conserved regulatory elements:

Figure 2: Integrated Workflow for Identifying and Validating Conserved Regulatory Elements. This pipeline combines computational prediction using both sequence and binding-site cluster conservation approaches with experimental validation to identify functional cis-regulatory modules across species.

Successful investigation of regulatory conservation requires specialized reagents and computational resources:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| TFBS Databases | CollecTF, JASPAR | Provide curated transcription factor binding motifs | Experimentally validated PWMs; taxonomy-wide coverage; transparent curation [5] |

| Genome Browsers | NCBI Genome Data Viewer, Ensemble | Visualize genomic contexts of predicted elements | Annotation of promoters, exons, introns; regulatory element mapping [2] |

| Motif Analysis Tools | MEME Suite (MCAST) | Identify statistically significant TFBS clusters | Scans for clusters of matches to multiple motifs; customizable parameters [2] |

| Synteny Mapping Tools | Interspecies Point Projection (IPP) | Identify orthologous regions independent of sequence | Uses bridged alignments with multiple species; overcomes alignment limitations [4] |

| Experimental Validation | Transgenic reporter constructs, ChIP-seq antibodies | Functional testing of predicted regulatory elements | Conserved epitope antibodies for multi-species ChIP; minimal promoter reporters [1] [3] |

The comparative analysis of sequence conservation versus binding-site cluster conservation reveals complementary rather than competing approaches for identifying functional regulatory elements. Sequence conservation remains highly effective for identifying deeply conserved regulatory elements, particularly in closely related species and for elements under strong purifying selection. In contrast, binding-site cluster conservation demonstrates superior performance for detecting functional elements across larger evolutionary distances, where sequence similarity may be minimal but architectural and functional conservation persists.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice of approach should be guided by specific research questions. Sequence-based methods are optimal for studying conservation among closely related species or identifying elements with strong functional constraints. Binding-site cluster approaches are essential for comparative studies across distantly related organisms, investigating regulatory innovation, and understanding how regulatory architecture evolves. The most powerful contemporary strategies integrate both approaches, leveraging their complementary strengths to comprehensively map the evolving regulatory landscape across species, tissues, and developmental contexts.

Transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) demonstrate a striking paradox in their evolutionary dynamics: while many sites undergo rapid turnover, a core set remains evolutionarily stable over deep phylogenetic timescales. This analysis compares the functional significance of these stable TFBS against their lineage-specific counterparts, synthesizing experimental data from multi-species studies to demonstrate that evolutionarily conserved TFBS are disproportionately associated with essential biological pathways, core developmental genes, and human disease mechanisms. Through systematic evaluation of quantitative data from liver, heart, stem cell, and bacterial systems, we establish that conserved cis-regulatory modules (CRMs) serve as critical hubs in the regulatory architecture of complex organisms, providing a framework for prioritizing functional non-coding genetic variation in disease research.

Gene regulatory evolution occurs primarily through changes in cis-regulatory elements, particularly transcription factor binding sites, which exhibit a complex pattern of conservation and divergence across species. While early studies suggested widespread conservation of regulatory elements, high-throughput comparative analyses have revealed that TFBS evolution is characterized by substantial turnover, with only a minority of sites conserved across large evolutionary distances [6] [4]. This rapid evolution creates a challenging landscape for distinguishing functionally significant regulatory elements from neutral binding events.

The development of multi-species ChIP-seq, DAP-seq, and other high-throughput mapping technologies has enabled researchers to identify a core set of evolutionarily stable TFBS that persist across deep phylogenetic divides. These conserved elements appear to represent a foundational layer of gene regulatory architecture that underlies essential cellular processes and developmental programs. This analysis systematically evaluates the functional significance of these evolutionarily stable TFBS through comparative analysis of experimental data across multiple species and biological contexts.

Quantitative Analysis of TFBS Conservation Patterns

Conservation Rates Across Evolutionary Distances

Table 1: Evolutionary Conservation of Regulatory Elements Across Taxonomic Groups

| Element Type | Human-Mouse Conservation | Human-Chicken Conservation | Human-Great Ape Conservation | Key Associated Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver TFBS | 21-37% [3] | N/A | N/A | Liver metabolism, blood coagulation, lipid metabolism [3] |

| Enhancers (Heart) | ~10% (sequence conservation) [4] | 42% (with synteny) [4] | N/A | Heart development, patterning [4] |

| hESC Enhancers | <5% [7] | N/A | >80% [7] | Pluripotency, embryogenesis, lineage specification [7] |

| Plant TFBS | N/A | N/A | 150 million years conservation [8] | Drought tolerance, stress response [8] |

Functional Associations of Conserved TFBS

Table 2: Functional Categories Enriched in Evolutionarily Stable TFBS

| Biological System | Conserved TFBS Association | Experimental Validation | Disease Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver Metabolism | Co-regulated liver genes; essential pathways [3] | Shared CRMs in human, macaque, mouse, rat, dog [3] | Blood coagulation disorders, lipid metabolism diseases [3] |

| Stem Cell Biology | Core pluripotency network [7] | Functional enhancer assays in hESC [7] | Cancer lethality, developmental disorders [7] |

| Heart Development | Cardiac patterning genes [4] | In vivo reporter assays in mouse [4] | Congenital heart disease |

| Bacterial Stress Response | Antibiotic resistance regulation [9] | Sort-seq repression strength mapping [9] | Antibiotic treatment failure |

Experimental Methodologies for TFBS Conservation Analysis

Multi-Species ChIP-Seq Protocol

The chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) protocol has been adapted for comparative studies across multiple species. Key modifications include:

Cross-species Antibody Validation: Antibodies raised against conserved epitopes must be validated for cross-reactivity in all study species [3]. For liver TF studies, antibodies against HNF4A, CEBPA, ONECUT1, and FOXA1 demonstrated conserved recognition across human, macaque, mouse, rat, and dog [3].

Tissue Matching: Physiological and developmental stages must be carefully matched. Liver studies utilized primary tissue from adults with comparable physiological states [3], while heart development studies used equivalent embryonic stages (E10.5 in mouse, HH22 in chicken) [4].

Peak Calling Consistency: Uniform bioinformatic processing across species using tools such as MACS2 with consistent statistical thresholds enables comparable binding site identification [10].

Orthology Determination: For closely related species, sequence-based alignment (LiftOver) suffices, but for distantly related species (e.g., mouse-chicken), synteny-based approaches like Interspecies Point Projection (IPP) dramatically improve ortholog detection [4].

Birth-Death Evolutionary Modeling

This computational framework estimates TFBS evolutionary rates without relying solely on base-by-base alignments:

Rate Estimation: Birth (λ) and death (μ) rates are estimated from TF motif counts within orthologous sequences across a known phylogeny [6] [11].

Ancestral State Reconstruction: The most likely number of TFBS at each phylogenetic node is calculated using maximum likelihood approaches [11].

Lineage Assignment: Individual TFBS are assigned to evolutionary branches based on the reconstructed ancestral states [11].

Application to six transcription factors (GATA1, SOX2, CTCF, MYC, MAX, ETS1) revealed that 58-79% of human binding sites originated since human-mouse divergence, with over 15% unique to hominids [6] [11].

DAP-Seq for Cross-Species TFBS Mapping

DNA Affinity Purification Sequencing (DAP-seq) enables high-throughput TFBS mapping across multiple species:

In Vitro TF Production: Transcription factors are expressed in vitro without requiring species-specific antibodies [8].

Genomic DNA Fragmentation: Native genomic DNA from each species is fragmented to create representative libraries [8].

Multiplexed Barcoding: Species-specific barcodes enable simultaneous processing of multiple genomes in a single experiment, reducing technical variability [8].

Integration with Single-Cell Data: Combining DAP-seq binding maps with single-nuclei RNA sequencing links TFs to specific cell types and regulatory networks [8].

This approach has successfully mapped ~3,000 genome-wide binding maps for 360 transcription factors across 10 plant species spanning 150 million years of evolution [8].

Visualizing Regulatory Evolution: Pathways and Workflows

Evolutionary Fates of Functional Enhancers

Multi-Species TFBS Identification Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for TFBS Conservation Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Example | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-TF Antibodies | Chromatin immunoprecipitation of specific TFs | Cross-species ChIP-seq for liver TFs [3] | Must target conserved epitopes; require validation in each species |

| Universal Protein-Binding Microarray | High-throughput TF binding affinity measurement | UniProbe database with 32,896 8-mer sequences [12] | In vitro system; may not capture chromatin context |

| DAP-seq Platform | In vitro TFBS mapping without antibodies | 360 transcription factors across 10 plant species [8] | Enables multiplexed cross-species comparisons |

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing | DNA methylation profiling at single-base resolution | Methylation patterns in TF binding regions [10] | Critical for epigenetic dimension of TFBS evolution |

| Sort-Seq Reporter System | High-throughput measurement of regulatory activity | TetR TFBS landscape mapping (17,851 variants) [9] | Links sequence to regulatory function quantitatively |

| Birth-Death Model Algorithms | Computational inference of TFBS evolutionary history | Lineage-specific binding site identification [6] [11] | Alignment-free method for ancient reconstruction |

| Dehydrocrebanine | Dehydrocrebanine | High-Purity Reference Standard | High-purity Dehydrocrebanine for research. Explore its applications in neuroscience and oncology. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| Octadecanal | Octadecanal | High-Purity Fatty Aldehyde | RUO | Octadecanal (Stearaldehyde), a C18 fatty aldehyde. For research into lipid metabolism, fragrance, and material science. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Evolutionarily stable TFBS represent a functionally privileged class of regulatory elements that disproportionately contribute to essential biological processes and disease mechanisms. The consistent association of conserved cis-regulatory modules with core developmental genes and pathways across diverse biological systems underscores their critical importance in maintaining organismal function. For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings suggest strategic approaches for prioritizing non-coding genomic regions in disease studies: elements conserved across deep evolutionary timescales represent high-value targets for understanding fundamental regulatory mechanisms and developing therapeutic interventions. The experimental frameworks and computational tools summarized here provide a roadmap for systematic identification and functional characterization of these critical regulatory elements across diverse biological contexts and disease states.

A fundamental goal in genomics is to understand how gene regulatory information is encoded in DNA sequence and how this code evolves across species. Transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs)—short DNA sequences recognized by transcription factors—serve as the fundamental units of gene regulatory networks. While protein-coding sequences have relatively straightforward conservation patterns, the evolutionary dynamics of TFBSs present a more complex picture. Evidence from both Drosophila and mammalian systems reveals a surprising paradox: despite deep conservation of transcriptional regulatory networks and transcription factor specificities, the binding sites themselves often exhibit remarkable sequence divergence. This guide systematically compares the experimental approaches, findings, and emerging principles from these two foundational model systems, providing researchers with a framework for evaluating conservation in their own systems of interest.

Core Concepts and Terminology

Table 1: Key Terminology in Comparative Regulatory Genomics

| Term | Definition | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factor Binding Site (TFBS) | Short, specific DNA sequence recognized and bound by a transcription factor | Basic functional unit of transcriptional regulation |

| cis-Regulatory Module (CRM) | Compact genomic region containing clusters of TFBSs that control specific aspects of gene expression | Functional unit of gene regulation; often ~1 kb in size |

| Direct Conservation (DC) | Regulatory elements identifiable through standard sequence alignment methods | Represents classically conserved non-coding elements |

| Indirect Conservation (IC) | Functionally conserved regulatory elements with highly diverged sequences, identifiable through synteny | Explains "conservation without sequence alignment" phenomenon |

| Binding Site Turnover | Evolutionary process where TFBSs are gained and lost while maintaining regulatory function | Contributes to sequence divergence despite functional conservation |

| Synteny | Preservation of genomic context and gene order between species | Powerful tool for identifying orthologous regulatory regions |

Conservation of Transcription Factor Binding Specificities

Deep Evolutionary Conservation of DNA Recognition

A foundational finding from comparative studies is the remarkable conservation of transcription factor binding specificities across vast evolutionary distances. Systematic analysis using HT-SELEX to characterize DNA binding specificities for approximately 900 Drosophila transcription factors revealed that orthologous pairs of TF DNA-binding domains (DBDs) between Drosophila and humans almost invariably recognize highly similar DNA sequences, despite approximately 600 million years of divergence [13].

This conservation of binding specificity is particularly striking when compared to other protein interaction domains. While many TF DBD families show extremely high conservation, several families exhibit conservation levels similar to other interaction domains like kinase domains, SH3, and SH2 domains [13]. The finding that DNA binding preferences are more conserved than overall protein sequence would predict suggests strong negative selection pressure on TF DNA recognition motifs.

Structural Determinants of Specificity Conservation

The conservation of binding specificity is primarily determined by the structural family of the transcription factor [13]. For example:

- bHLH proteins maintain recognizably similar E-box preferences

- Homeodomain proteins conserve their distinct DNA recognition patterns

- Nuclear receptor family members maintain characteristic binding signatures

This structural constraint explains how orthologous TFs can recognize similar sequences despite significant sequence divergence in both the TFs themselves and their target binding sites.

Drosophila Models: Precision Tools for Dissecting Regulatory Logic

Experimental Paradigms in Drosophila Research

Table 2: Key Experimental Approaches in Drosophila Regulatory Genomics

| Method | Application | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| In vivo enhancer testing | Testing predicted CRMs attached to reporter genes in transgenic embryos | 6 of 27 predicted clusters functioned as enhancers for adjacent genes [14] |

| Binding site clustering analysis | Identifying dense clusters of predicted TFBSs as candidate CRMs | Conservation of binding-site clusters accurately discriminates functional from non-functional regions [14] |

| Population genomics | Analyzing TFBS variation across 162 isogenic Drosophila lines | 24-28% of bound sites contained SNPs; variation anti-correlates with positional information content [15] |

| HT-SELEX | High-throughput characterization of TF binding specificities | Generated DNA binding motifs for ~230 Drosophila TFs; enabled cross-species comparison [13] |

Quantitative Insights from Drosophila Studies

Drosophila research has yielded several key quantitative insights into TFBS conservation:

- Cluster conservation predicts function: Comparison between D. melanogaster and D. pseudoobscura revealed that conservation of binding-site clusters accurately discriminates functional regions from non-functional ones, while conservation of primary sequence alone cannot [14].

- Variation patterns reflect constraints: For TFs Twist, Biniou, and Tinman, weaker PWM-scoring motifs showed higher levels of individual variation (2.9% SNP frequency in Drosophila), consistent with purifying selection acting on functional sites [15].

- Functional buffering of variation: Evidence suggests TFBS mutations, particularly at evolutionarily conserved sites, can be efficiently buffered to ensure coherent levels of transcription factor binding [15].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for identifying and validating conserved regulatory elements in Drosophila. The approach integrates computational prediction with experimental validation in transgenic models, followed by comparative analysis to distinguish different types of conservation.

Mammalian Systems: Complexity and Long-Range Conservation

Experimental Frameworks in Mammalian Research

Table 3: Key Experimental Approaches in Mammalian Regulatory Genomics

| Method | Application | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Interspecies Point Projection (IPP) | Synteny-based algorithm to identify orthologous regulatory regions independent of sequence alignment | Identified 5× more conserved enhancers between mouse and chicken than alignment-based methods [4] |

| Multi-species ChIP-seq | Comparing TF binding across multiple mammalian species | Rapid TF binding turnover observed; cooperative binding changes among cobound TFs [16] |

| Bag-of-Motifs (BOM) modeling | Representing regulatory elements as unordered motif counts for classification | Accurately predicts cell-type-specific enhancers across species (93% accuracy in mouse E8.25 embryos) [17] |

| MORALE framework | Domain adaptation for cross-species prediction of TF binding | Enables deep learning models to learn species-invariant regulatory features [18] |

Quantitative Insights from Mammalian Studies

Mammalian comparative genomics has revealed distinct patterns of regulatory evolution:

- Extensive hidden conservation: In mouse-chicken comparisons (approximately 300 million years divergence), only ~10% of enhancers show sequence conservation, but synteny-based methods (IPP) reveal >42% positional conservation—a fivefold increase [4].

- Cooperative binding evolution: In closely related mammals, cobound TFs change their genomic binding cooperatively, with most binding differences occurring without nearby sequence variations in core motifs [16].

- Cross-species prediction advances: The MORALE framework enables effective cross-species prediction of TF binding by aligning statistical moments of sequence embeddings across species [18].

Direct Comparative Analysis: Drosophila vs. Mammalian Systems

Quantitative Comparison of Evolutionary Dynamics

Table 4: System-Level Comparison of TFBS Conservation Patterns

| Feature | Drosophila | Mammals |

|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary rate of TF binding | Slower, more constrained | Faster turnover, particularly in rodents [16] |

| Sequence conservation of enhancers | Moderate (~50% conserve between closely related species) | Low (~10% between mouse-chicken) [4] |

| Positional conservation | Not systematically quantified | Extensive (42% between mouse-chicken using IPP) [4] |

| Nature of binding changes | More quantitative, graded differences | More qualitative, cooperative shifts [16] |

| Population variation | Higher (2.9% SNP frequency at TFBS) | Lower (0.25% in human CEU population) [15] |

| Effective population size | Larger | Smaller |

| Key identification method | Binding site cluster conservation | Synteny-based positional conservation |

Shared Principles Despite Different Dynamics

Despite the differing evolutionary dynamics, both systems share important principles:

- Functional conservation without sequence alignment: Both systems show evidence of conserved regulatory function despite sequence divergence. The even-skipped stripe 2 enhancer maintains function among insects despite high sequence divergence [4], paralleling the "indirectly conserved" elements in mammals.

- Importance of clustering: In both Drosophila and mammals, clustering of TFBSs appears crucial for function, whether analyzed through conservation of site clusters [14] or through Bag-of-Motifs representations that discard spacing information [17].

- Buffering of variation: Both systems show evidence that TFBS mutations can be buffered at the level of binding or function, particularly at evolutionarily conserved sites [15].

Figure 2: Comparative analysis of TFBS conservation mechanisms in Drosophila versus mammalian systems. While evolutionary dynamics differ substantially, both systems share fundamental principles of regulatory conservation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Application and Function |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Assays | HT-SELEX, ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, transgenic reporter assays (Drosophila), in vivo enhancer assays (mouse) | Mapping TF binding and validating enhancer function across species |

| Genome Resources | D. melanogaster and D. pseudoobscura genomes; multiple mammalian reference genomes; DGRP flies; 1000 Genomes data | Providing sequence and variation data for comparative analyses |

| Computational Tools | Interspecies Point Projection (IPP), Bag-of-Motifs (BOM), MORALE, EEL, GimmeMotifs, FIMO | Identifying conserved elements and predicting regulatory function across species |

| Key Datasets | modENCODE TF binding maps, ENCODE human TF maps, multi-species embryonic chromatin profiles | Pre-computed binding information for comparative analyses |

| Epifriedelanol acetate | Epifriedelanol Acetate | High-Purity Reference Standard | High-purity Epifriedelanol acetate for cancer & metabolic research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Dihexyl phthalate | Dihexyl Phthalate | High-Purity Plasticizer | RUO | Dihexyl Phthalate is a high-purity plasticizer for materials science research. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. |

Emerging Principles and Future Directions

The integration of evidence from Drosophila and mammalian systems reveals a more nuanced understanding of regulatory evolution than previously appreciated. The emerging principles include:

- Deep conservation of TF binding specificities despite widespread binding site turnover

- Functional conservation through different mechanisms—cluster conservation in Drosophila versus positional conservation in mammals

- Importance of comparative frameworks that go beyond simple sequence alignment

- Power of machine learning approaches like BOM and MORALE that capture higher-order features of regulatory sequences

These principles provide a foundation for future research aimed at understanding human regulatory variation and its relationship to disease. The experimental and computational approaches summarized here offer researchers multiple entry points for investigating gene regulation in their own systems of interest, with appropriate choice of model system depending on the specific biological questions being addressed.

The regulation of gene expression is a fundamental process in biology, and transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) serve as the key genomic sequences that control this process. Comparative genomics has revealed that a significant portion of non-coding sequences, including TFBSs, is under functional constraint through evolution [19]. The core thesis underpinning this field posits that conserved TFBSs are not merely sequence artifacts but represent functional elements with critical roles in essential biological processes. Studies across diverse organisms—from yeast to humans—consistently demonstrate that TFBSs with significant evolutionary conservation are disproportionately associated with genes involved in crucial cellular functions, developmental programs, and tissue-specific pathways [20] [21] [22].

The investigation of conserved regulatory makeup represents a powerful approach for distinguishing functional TFBSs from the vast landscape of non-functional genomic sequences. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the experimental methods, analytical frameworks, and emerging insights in the field of TFBS conservation analysis, with particular emphasis on the demonstrated linkage between conservation and biological function.

Methodological Comparison: Approaches for Conserved TFBS Analysis

Experimental and Computational Workflows

Researchers employ diverse methodological frameworks to identify and validate conserved TFBSs. The table below summarizes the core approaches, their applications, and key findings regarding functional conservation.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Methods for Studying Conserved TFBS

| Method | Key Principle | Application Scope | Functional Linkage Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positional Regulomics [23] | Identifies TFBS with positional preferences relative to genomic landmarks (e.g., TSS) | Genome-scale analysis of putative promoter regions | Gene groups with common TFBS show similar expression profiles and biological functions |

| Multi-Species ChIP-seq [20] [21] | Compares experimentally determined TF binding events across species | Identification of conserved binding events in specific tissues/cell types | Conserved TFBS show stronger correlation with conserved gene expression patterns |

| DAP-seq [8] | In vitro mapping of TF binding using purified TFs and genomic DNA | High-throughput mapping across multiple species, especially plants | Conservation scores identify functionally critical regulatory elements |

| Binding Site Clustering Analysis [24] | Identifies clustered TFBS as candidate cis-regulatory modules | Genomic screening for developmental enhancers | Conservation of binding-site clustering accurately discriminates functional CRM |

| MONKEY Algorithm [25] | Binding site-specific evolutionary model applied to multiple alignments | Phylogenetic identification of constrained TFBS | Statistical evaluation of conservation significance based on evolutionary distance |

Quantitative Relationships Between Conservation and Function

Rigorous quantitative analyses have established compelling relationships between TFBS conservation and functional impact:

Gene Expression Correlation: Analysis of TF binding events in hepatocytes and embryonic stem cells revealed that genes with conserved TFBSs in their promoters show significantly higher conservation of expression patterns between human and mouse compared to genes with non-conserved binding events [20]. The conditional probability of binding conservation increases markedly when the target gene is expressed in both species.

Combinatorial Binding Effects: The functional impact of conservation is magnified for groups of TFBSs. Studies demonstrate that when multiple TFs bind a promoter, their joint conservation shows stronger association with conserved gene expression than individual TFBS conservation [20].

Evolutionary Distance Effects: Research in yeast species revealed that the probability of a non-functional TFBS being conserved by chance alone is remarkably low (approximately 0.002 for a 10-bp sequence across three Saccharomyces species), enabling reliable functional annotation based on conservation [19].

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual relationship between TFBS conservation and its functional implications across evolutionary timescales.

Experimental Protocols for Conserved TFBS Identification

Multi-Species Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP-seq)

The simultaneous analysis of transcription factor binding across multiple species represents a powerful approach for identifying conserved regulatory elements with functional significance [21].

Protocol Overview:

- Sample Preparation: Isolate primary tissue from multiple species under physiologically comparable conditions. Liver tissue has proven particularly suitable due to its cellular homogeneity (~75% hepatocyte nuclei) [21].

- Cross-linking and Immunoprecipitation: Treat tissue with formaldehyde for DNA-protein cross-linking; perform chromatin shearing; incubate with validated antibodies raised against conserved TF epitopes.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Construct sequencing libraries from immunoprecipitated DNA; sequence on high-throughput platforms.

- Peak Calling and Alignment: Identify significant binding peaks in each species; map to respective genomes.

- Orthologous Region Identification: Define orthologous genomic regions using whole-genome alignments.

- Conservation Analysis: Classify binding events as conserved when occurring in orthologous regions across species.

Functional Validation: Conserved binding events identified through this approach show strong association with tissue-specific biological pathways. For example, shared cis-regulatory modules in liver tissue are enriched near genes involved in blood coagulation and lipid metabolism pathways [21].

DAP-seq for High-Throughput Cross-Species Profiling

DNA Affinity Purification Sequencing (DAP-seq) has emerged as a scalable alternative for mapping TF binding sites across multiple species, particularly in plant genomics [8].

Protocol Overview:

- TF Expression and Barcoding: Express transcription factors in vitro; multiplex using species-specific barcoding.

- Genomic DNA Preparation: Fragment genomic DNA from target species; prepare libraries.

- Affinity Purification: Incubate TFs with genomic DNA; perform consecutive affinity purification.

- Sequencing and Data Integration: Sequence bound DNA fragments; integrate with single-cell RNA expression maps.

- Conservation Scoring: Identify TFBS with high conservation scores across species.

Recent Innovations: Updated DAP-seq protocols incorporate stricter filtering criteria and integrate TF binding data with single-cell transcriptomes, enabling researchers to infer which TFs shape specific cell identities [8].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Conserved TFBS Analysis

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Databases | TRANSFAC [23], DBTSS [23], Plant TFDB [22] | Reference databases for known TFBS and motifs | Curated collections of experimentally validated binding sites |

| Genomic Resources | Ensembl Plants [22], DAP-seq data portals [8] | Access to orthologous genes and promoter sequences | Pre-computed orthology relationships and alignment tools |

| Computational Tools | MONKEY [25], FIMO [22], Minimap2 [22] | Identification of conserved TFBS in alignments | Binding site-specific evolutionary models, motif enrichment analysis |

| Antibody Resources | Validated ChIP-grade antibodies against conserved epitopes [21] | Multi-species ChIP experiments targeting specific TFs | Antibodies raised against conserved protein domains for cross-species compatibility |

Biological Pathways and Processes Enriched for Conserved TFBS

Tissue-Specific Functional Enrichment

Cross-species analyses consistently identify specific biological pathways that demonstrate remarkable conservation of regulatory control:

Liver-Specific Pathways: Multi-species ChIP-seq of liver-enriched transcription factors (HNF4A, CEBPA, ONECUT1, FOXA1) revealed that conserved cis-regulatory modules are preferentially associated with genes involved in critical hepatic functions, including blood coagulation cascades and lipid metabolism [21]. Disease-associated mutations from genome-wide association studies are significantly enriched in these conserved regulatory regions.

Developmental Programs: In Drosophila, conserved clusters of transcription factor binding sites accurately distinguish functional enhancers that control embryonic patterning genes [24]. These conserved regulatory modules drive expression of key developmental regulators including giant, fushi tarazu, and odd-skipped.

Starch Biosynthesis in Plants: Comparative analysis of common bean regulatory networks identified ERF, MYB, and bHLH transcription factor families as having conserved binding sites near starch biosynthesis genes, highlighting the conservation of metabolic pathway regulation [22].

Quantitative Functional Impact

The functional significance of conserved TFBS is demonstrated through rigorous quantitative measures:

Enhanced Expression Impact: Conserved TF binding events exert a greater influence on the expression of their target genes compared to non-conserved binding events [20]. This relationship holds across diverse cell types and developmental stages.

Evolutionary Stability: Transcription factor binding preferences show remarkable stability over evolutionary timescales—DAP-seq studies have identified nearly identical binding sites for proteins from grasses and trees that diverged 150 million years ago [8].

The diagram below illustrates the experimental workflow for multi-species conserved TFBS analysis and its connection to functional validation.

Emerging Frontiers: Expansion of Regulatory Code Through TF Interactions

Recent research has revealed that the complexity of conserved regulatory control extends beyond individual TFBS to encompass sophisticated interaction networks:

DNA-Guided TF Interactions: Large-scale interaction screening of over 58,000 TF-TF pairs has identified 2,198 interacting pairs, with 1,329 showing preferential binding to motifs arranged in distinct spacing/orientation and 1,131 forming novel composite motifs [26]. These interactions dramatically expand the regulatory lexicon.

Cooperativity and Specificity: TF-TF interactions commonly cross family boundaries, with different family members showing distinct spacing preferences with the same interaction partners [26]. This explains how TFs with similar binding specificities can achieve distinct biological functions—resolving paradoxes such as the "hox specificity paradox" where homeodomain proteins with identical TAATTA binding motifs execute distinct developmental functions.

Cell-Type-Specific Regulation: Novel composite motifs identified through interaction screens are enriched in cell-type-specific regulatory elements and are more likely to be formed between developmentally co-expressed TFs [26]. This represents a crucial mechanism for achieving specific transcriptional outcomes using a limited repertoire of TFs.

The comprehensive analysis of conserved transcription factor binding sites across multiple species and experimental platforms consistently demonstrates that sequence conservation serves as a powerful indicator of biological function. Conserved TFBS are disproportionately associated with essential biological processes, tissue-specific functions, and evolutionary constrained developmental programs. The emerging paradigm reveals a complex regulatory code where conserved binding sites serve as functional anchors within broader interaction networks, with conservation metrics providing critical filters for distinguishing functional elements from the background of genomic sequences. As methods for high-throughput binding site mapping and cross-species comparison continue to advance, the linkage between TFBS conservation and biological function will undoubtedly yield further insights into the fundamental principles of gene regulatory evolution.

Transcription factors (TFs) are fundamental regulators of gene expression that bind specific DNA sequences to control diverse biological processes, including development, metabolism, and stress responses. Among the numerous TF families in eukaryotic genomes, three families stand out for their remarkable conservation across evolutionary timescales: the AP2/ERF (Ethylene Response Factor), MYB (myeloblastosis), and bHLH (basic helix-loop-helix) families. These families have undergone significant expansion in plants while maintaining conserved structural and functional characteristics across distantly related species.

Understanding the conservation patterns of these TF families provides crucial insights into the evolution of gene regulatory networks and the molecular basis of morphological diversity. Despite hundreds of millions of years of independent evolution, core DNA-binding specificities and protein-protein interaction capabilities remain strikingly conserved, suggesting strong evolutionary constraints on these regulatory proteins. This guide systematically compares the conservation patterns of ERF, MYB, and bHLH transcription factor families, providing experimental data and methodologies relevant to researchers investigating gene regulatory evolution and transcriptional regulation in both plant and animal systems.

The ERF, MYB, and bHLH transcription factor families represent some of the largest and most functionally diverse groups of transcriptional regulators across eukaryotic organisms. Comparative genomic analyses reveal substantial variation in family sizes between species, reflecting both evolutionary expansions and specific adaptations.

Table 1: Genomic Distribution of ERF, MYB, and bHLH Transcription Factor Families Across Species

| Species | ERF Family Members | MYB Family Members | bHLH Family Members | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 122 | 197 (R2R3: ~70%) | 162 | [27] [28] [29] |

| Oryza sativa (rice) | 139 | 155 (R2R3: ~57%) | 111 | [27] [28] [29] |

| Panax ginseng | Not reported | Not reported | 169 | [30] |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | Not reported | 38 | 8 | [29] |

| Drosophila melanogaster | Not applicable | Not applicable | 242 | [31] |

| Homo sapiens | Not applicable | Not applicable | 108 | [32] |

The expansion of these transcription factor families in higher plants compared to basal lineages demonstrates their crucial role in plant-specific processes. For instance, the ERF family in Arabidopsis contains 122 members, while rice has 139 members, with both species maintaining similar subgroup organizations despite evolutionary divergence [27]. The MYB family shows similar expansion patterns, with R2R3-MYB proteins representing the predominant subclass in higher plants [28] [29]. The bHLH family exhibits remarkable conservation between animals and plants, with Drosophila having 242 bHLH genes compared to 108 in humans [32] [31].

Structural Conservation and DNA-Binding Specificities

Domain Architecture and Motif Conservation

Each transcription factor family possesses characteristic DNA-binding domains that show remarkable evolutionary conservation:

ERF Family: Characterized by a single AP2/ERF domain of approximately 60-70 amino acids that forms a three-dimensional structure resembling the minor groove-binding domain of the histone-fold protein HMFB [27]. The ERF family is divided into two major subfamilies (ERF and CBF/DREB) based on sequence similarities and binding specificities.

MYB Family: Defined by the MYB DNA-binding domain, typically consisting of 1-4 imperfect repeats of approximately 52 amino acids each [28]. Plant MYB proteins are classified into four major groups: 1R-MYB, R2R3-MYB, R1R2R3-MYB, and 4R-MYB, with R2R3-MYB representing the most abundant class in higher plants [28] [29].

bHLH Family: Possesses the characteristic basic helix-loop-helix domain, where the basic region mediates DNA binding while the HLH region facilitates dimerization [33] [32]. The bHLH domain recognizes the canonical E-box (CANNTG), with specificity determined by nucleotide variations at the central positions [33] [31].

DNA Recognition Specificities

Table 2: DNA-Binding Specificities of ERF, MYB, and bHLH Transcription Factor Families

| TF Family | Primary Recognition Sequence | Specificity Variations | Structural Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERF | GCC box (AGCCGCC) | DREB/CBF subfamily recognizes dehydration-responsive element (DRE) with A/GCCGAC | Single AP2/ERF domain with three β-sheets [27] |

| MYB | Consensus: CNGTTR | Specific recognition determined by residues in the third helix of each repeat | MYB repeats form helix-turn-helix structures; R2R3-MYB predominates in plants [28] [29] |

| bHLH | E-box (CANNTG) | Specificity determined by central nucleotides; TWIST recognizes double E-box with 5-nt spacing | Basic region binds major groove; HLH domain mediates dimerization [33] [32] [31] |

The bHLH family demonstrates particularly striking conservation of DNA-binding specificities. Systematic comparisons between Drosophila and human bHLH proteins reveal that binding specificities are highly conserved, extending even to subtle dinucleotide preferences [31]. For example, the TWIST subfamily of bHLH proteins recognizes a unique double E-box motif with two E-boxes spaced preferentially by 5 nucleotides, a specificity conserved from Drosophila to humans [33].

Evolutionary Conservation Across Species

Sequence and Functional Conservation

Comparative analyses reveal different degrees of conservation across these TF families:

Deep Evolutionary Conservation: The bHLH family demonstrates extraordinary conservation, with DNA-binding specificities maintained across 600 million years of bilaterian evolution [31]. Orthologous TFs between Drosophila and mammals show nearly identical binding preferences, suggesting strong evolutionary constraints.

Plant-Specific Expansions: The ERF and MYB families have undergone significant expansion in plants compared to other lineages. The ERF family in Arabidopsis and rice diverged into 12 and 15 groups respectively, with 11 groups common to both species, indicating functional diversification before the monocot-dicot divergence [27].

Conservation of Regulatory Complexes: The MYB and bHLH families frequently interact in regulatory complexes, particularly the well-characterized MYB-bHLH-WD40 (MBW) complex that regulates flavonoid and anthocyanin biosynthesis in plants [29] [34]. This cooperative interaction represents a conserved functional module across plant species.

Mechanisms of Family Expansion and Diversification

Gene duplication events represent the primary mechanism for transcription factor family expansion:

Whole Genome Duplication: Segmental and chromosomal duplications have contributed significantly to the expansion of ERF, MYB, and bHLH families in plants [27] [28].

Tandem Duplications: Local gene duplications have generated clusters of related transcription factors, allowing for functional diversification while maintaining core DNA-binding capabilities [27] [29].

Subfunctionalization: Following duplication events, paralogous genes often undergo functional specialization, acquiring distinct expression patterns or regulatory specificities while conserving ancestral protein functions [27] [29].

Experimental Approaches for Studying TF Conservation

Genomic and Computational Methods

Several experimental approaches have been developed to study transcription factor conservation:

Figure 1: Workflow for Computational Analysis of TF Conservation

Comparative Genomics: Identification of transcription factor families across multiple sequenced genomes using conserved domain searches [27] [28]. For example, BLAST searches with conserved domains (AP2/ERF, MYB, or bHLH) against genomic databases followed by manual curation.

Phylogenetic Analysis: Reconstruction of evolutionary relationships within TF families using multiple sequence alignment and tree-building algorithms [27] [28] [30]. This approach reveals subgroup diversification and evolutionary relationships.

Synteny-Based Orthology Detection: Algorithms such as Interspecies Point Projection (IPP) identify orthologous regulatory regions beyond sequence similarity, particularly useful for distantly related species [4]. IPP uses syntenic relationships and bridging species to project regulatory elements between genomes.

Functional and Biochemical Assays

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP-seq): Genome-wide mapping of transcription factor binding sites [33]. High-resolution ChIP-seq reveals in vivo binding specificities and conservation of binding sites between species.

HT-SELEX (High-Throughput Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment): Systematic determination of DNA binding specificities for hundreds of transcription factors [31]. This high-throughput method involves multiple cycles of binding, partitioning, and amplification using random oligonucleotide libraries.

Protein-Binding Microarrays: Alternative high-throughput method for characterizing DNA binding specificities [31].

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA): Validation of specific TF-DNA interactions using purified proteins and labeled DNA probes [32].

Yeast One-Hybrid and Two-Hybrid Systems: Investigation of DNA-binding and protein-protein interactions, respectively [34].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Transcription Factor Conservation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Anti-TWIST1, Anti-H3K27ac | Chromatin immunoprecipitation; protein localization |

| Cloning Systems | Gateway-compatible vectors, Yeast two-hybrid systems (pGBKT7, pGADT7) | Protein expression; interaction studies [34] |

| Reporter Systems | Luciferase, GUS, YFP | Promoter activity; protein localization [34] |

| Sequencing Kits | ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, RNA-seq | Binding site mapping; chromatin accessibility; expression profiling [33] [4] |

| Heterologous Expression | E. coli protein expression systems | Recombinant TF production for HT-SELEX [31] |

| Genomic Resources | Ensembl Plants, PlantTFDB, FlyTF.org | Orthology data; TF classification [35] [31] |

Key Experimental Findings and Case Studies

Conservation of bHLH Binding Specificities

A comprehensive comparison of 242 Drosophila TFs with human and mouse counterparts revealed that TF binding specificities are highly conserved between Drosophila and mammals, with conservation extending to subtle dinucleotide preferences [31]. This remarkable conservation persists despite approximately 600 million years of independent evolution, suggesting strong structural constraints on DNA-binding domains.

ERF Family Divergence in Plants

Comparative analysis of ERF families in Arabidopsis and rice demonstrated that major functional diversification within this family predated the monocot-dicot divergence [27]. The 122 ERF genes in Arabidopsis and 139 in rice are divided into 12 and 15 groups respectively, with 11 groups common to both species, indicating both conserved and lineage-specific expansions.

MYB-bHLH Interactions in Plant Pigmentation

The MYB and bHLH families functionally interact in the conserved MYB-bHLH-WD40 (MBW) complex that regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis [34]. Repressor MYB proteins like TgMYB4 contain a bHLH-binding motif that enables competitive interaction with bHLH partners, demonstrating how conserved interaction interfaces enable regulatory complexity [34].

Figure 2: MYB-bHLH Regulatory Complex in Anthocyanin Biosynthesis

Nucleosome Interactions and DNA Accessibility

Recent structural studies reveal that bHLH transcription factors like CLOCK-BMAL1 and MYC-MAX employ distinct strategies to access nucleosome-embedded E-boxes [32]. CLOCK-BMAL1 triggers DNA release from histones through PAS domain interactions with the histone octamer, while MYC-MAX shows preferential binding to nucleosomal entry-exit sites, demonstrating how conserved TFs adapt to chromatin environments.

Implications for Regulatory Evolution and Crop Improvement

The conservation patterns of ERF, MYB, and bHLH transcription families have significant implications for both basic biology and applied biotechnology:

Predictive Genomics: The high conservation of DNA-binding specificities enables accurate prediction of regulatory networks in non-model organisms based on data from reference species [35] [31].

Crop Engineering: Knowledge of conserved TF functions facilitates the transfer of regulatory modules between species for crop improvement. For example, understanding the conserved MYB-bHLH-WD40 complex enables targeted manipulation of anthocyanin pathways for enhanced nutritional value [34].

Synthetic Biology: Conserved TF DNA-binding specificities provide standardized parts for constructing synthetic gene circuits with predictable behaviors across diverse biological systems [31].

The exceptional conservation of these transcription factor families across evolutionary timescales underscores their fundamental importance in gene regulatory networks, while species-specific expansions and modifications illustrate how regulatory evolution contributes to biological diversity.

Comparative Genomics Approaches for TFBS Analysis: Practical Implementation

Understanding the evolution of gene regulation requires connecting gene ancestry with the conservation of its regulatory sequences. This guide examines computational pipelines that integrate ortholog identification with the subsequent discovery of conserved transcription factor binding sites (TFBS). The core premise is that genes with common ancestry (orthologs) often retain similar regulatory controls in their promoter regions, but the degree of TFBS conservation varies significantly across lineages and biological contexts [3] [36].

Accurately identifying orthologs is the critical first step, as errors at this stage propagate through the entire analysis. Following orthology assignment, computational models scan the regulatory regions of orthologous genes to find statistically overrepresented, conserved DNA motifs. These pipelines enable researchers to move from thousands of genomes to a shortlist of candidate regulatory elements crucial for tissue-specific function or disease [17] [35].

This guide objectively compares the performance, underlying algorithms, and optimal use cases for the leading tools in this field, providing a structured framework for selecting the right pipeline for cross-species regulatory genomics.

Orthology Inference: A Performance Comparison

The foundation of any cross-species comparison is the accurate identification of orthologous genes. The table below summarizes the benchmarked performance and characteristics of three modern orthology inference tools.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Modern Orthology Inference Tools

| Tool | Core Algorithm | Scalability (Time Complexity) | Benchmark Accuracy (Precision/Recall) | Key Differentiator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastOMA [37] [38] | K-mer-based placement + taxonomy-guided tree traversal | Linear | 0.955 Precision (SwissTree) | Linear scalability; uses reference HOGs from OMA database |

| OrthoGrafter [39] | Grafting queries onto precomputed PANTHER trees | N/A (Leverages precomputed trees) | High correlation with OMA orthologs | Rapid inference by leveraging Panther's curated gene trees |

| OrthoFinder [37] | All-against-all DIAMOND + gene tree inference | Quadratic | High Recall (General) | High sensitivity for inferring orthogroups |

Experimental Protocol for Orthology Benchmarking

The performance data in Table 1 is primarily derived from independent assessments coordinated by the Quest for Orthologs (QfO) consortium [37] [38]. The standard benchmarking protocol involves:

- Reference Dataset Curation: A set of model organisms with well-curated genomes and established "gold standard" orthologs is defined. This often includes the QfO reference proteome dataset.

- Tool Execution: Each orthology inference tool is run on the same set of input proteomes using default parameters.

- Performance Metric Calculation: Predictions are compared against the gold standard using several metrics:

- Precision: The fraction of predicted ortholog pairs that are correct (e.g.,

True Positives / (True Positives + False Positives)). This measures reliability. - Recall/Sensitivity: The fraction of true ortholog pairs that are successfully recovered (e.g.,

True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives)). This measures completeness. - Species Tree Discordance: The normalized Robinson-Foulds distance between a species tree inferred from the orthologs and a trusted reference species tree [37].

- Precision: The fraction of predicted ortholog pairs that are correct (e.g.,

From Orthologs to Motif Discovery: Methods & Models

Once orthologs are identified, the promoter sequences of orthologous gene groups are analyzed for conserved TFBS. The table below compares the dominant computational approaches for this task.

Table 2: Comparison of Motif Discovery and TFBS Prediction Methods

| Method | Approach | Interpretability | Reported Performance (auPR) | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bag-of-Motifs (BOM) [17] | Gradient-boosted trees on motif counts | High (Direct motif contribution) | 0.93 - 0.99 (Cell-type-specific CREs) | Predicting cell-type-specific enhancers |

| K-mer-based ML (k-mer grammar) [36] | Machine learning on k-mer frequencies | Medium (Requires motif matching) | 0.99 AUC (GLK binding prediction) | Accurate in vivo binding prediction from sequence |

| PSSM Enrichment (FIMO/HOMER) [35] [40] | Statistical overrepresentation of known motifs | High | Variable; depends on matrix quality [40] | Identifying known motifs in a set of sequences |

| Experimental Cistrome Comparison [3] [36] | Direct cross-species ChIP-seq peak overlap | High (Empirically determined) | N/A (Low conservation observed) | Ground-truth assessment of binding conservation |

Experimental Protocol for Motif Conservation Analysis

The workflow for identifying conserved TFBS in orthologous promoters is methodologically distinct from orthology inference.

- Promoter Sequence Extraction: Upstream regions (e.g., -2000 to +200 base pairs relative to the Transcription Start Site) of all genes in an orthologous group are extracted from each genome [35].

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Promoter sequences are aligned using tools like Minimap2 or MUSCLE to identify conserved blocks [35].

- Motif Scanning & Enrichment: Conserved regions are scanned with Position-Specific Scoring Matrices (PSSMs) from databases like JASPAR using tools such as FIMO (Find Individual Motif Occurrences). Motif enrichment is calculated by comparing the frequency of motif hits in the target sequences versus a background model [35] [40].

- Validation: Predictions can be validated against experimental cistrome data (e.g., ChIP-seq) from multiple species, when available. Functional validation may involve testing the regulatory potential of predicted motifs in reporter assays [36].

Integrated Analysis: Connecting Orthology and Binding site predictions

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data flow connecting the tools and analyses discussed in this guide, from raw genomic data to validated, conserved regulatory motifs.

Successful execution of a computational pipeline from orthology to motif enrichment relies on a suite of key resources.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for the Computational Pipeline

| Resource Name | Type | Function in the Pipeline | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| OMA Database [37] [38] | Reference Database | Provides Hierarchical Orthologous Groups (HOGs) for FastOMA and benchmark data. | Curated orthology relationships for over 2000 genomes. |

| PANTHER [39] | Precomputed Gene Trees | Source of curated gene trees for ortholog grafting with OrthoGrafter. | Manually curated gene families with reconciled trees. |

| JASPAR [40] | TF Motif Database | A source of non-redundant, curated PSSMs for motif scanning and enrichment. | High-quality, manually curated transcription factor binding profiles. |

| Ensembl Plants/Genomes [35] | Genomic Data Platform | Provides genome sequences, gene annotations, and precomputed orthologs for many species. | Centralized access to annotated genomes and comparative genomics data. |

| ChIP-seq Data [3] [36] | Experimental Data | Serves as ground truth for validating computationally predicted TFBS and assessing conservation. | Directly maps in vivo transcription factor binding locations. |

| GimmeMotifs [17] | Motif Analysis Toolkit | Used for motif discovery and scanning, often to create the input for the BOM framework. | Reduces motif redundancy and provides a unified motif analysis workflow. |

The field of computational genomics is rapidly advancing towards more integrated and scalable solutions. The tools compared here, such as FastOMA for its revolutionary linear scalability in orthology inference and BOM for its highly accurate and interpretable motif-based prediction of regulatory elements, represent the current state-of-the-art [37] [17].

A key finding reinforced by cross-species studies is that while the function of a transcription factor may be conserved, its binding sites often show remarkable divergence, with only a small fraction being conserved across deep evolutionary distances [3] [36]. This underscores the necessity of robust computational pipelines to distinguish functionally critical, conserved regulatory elements from the background of non-functional or species-specific binding events.

Future developments will likely involve the tighter integration of structural protein data to improve orthology resolution and the use of gene order conservation (synteny) as an additional layer of evidence [37] [38]. Furthermore, machine learning models that can directly integrate orthology information with sequence and chromatin data will provide even more powerful tools for deciphering the evolutionary dynamics of gene regulation.

Understanding the conservation of transcription factor (TF) binding sites is fundamental to deciphering the evolution of gene regulation. Multi-species Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has emerged as a powerful experimental strategy to directly map the genomic locations of TFs across different organisms, moving beyond predictions based solely on DNA sequence conservation. This approach reveals that while TF binding preferences (motifs) are often deeply conserved, the genomic locations of binding sites (the cistrome) can diverge significantly, a phenomenon known as cistrome turnover [41]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various multi-species ChIP-seq strategies, detailing their experimental protocols, key findings on conservation dynamics, and the computational tools that support this research.

Comparative Landscape of Multi-Species ChIP-seq Studies

The table below summarizes the design and primary conclusions of several pivotal multi-species ChIP-seq studies, highlighting the variability in conservation rates across different TFs, tissues, and evolutionary distances.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Multi-Species ChIP-seq Studies

| Study Organisms | Tissue/Cell Type | Transcription Factor(s) | Key Finding on Binding Conservation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human, Macaque, Mouse, Rat, Dog | Liver | HNF4A, CEBPA, ONECUT1, FOXA1 | ~2/3 of TF-bound regions fell into CRMs; | Ballester et al., 2014 [3] |

| Human, Mouse, Dog, Opossum, Chicken | Liver | CEBPA, HNF4A | Binding is largely species-specific; only 2% of CEBPA binding was shared between human and chicken. [41] | Schmidt et al., 2010 [41] |

| Tomato, Tobacco, Arabidopsis, Maize, Rice | Leaf & Green Fruit | GLK1, GLK2 | Most GLK binding sites are species-specific; conserved sites are often associated with photosynthetic genes. [36] | Li et al., 2022 [36] |

| Mouse, Chicken | Embryonic Heart | Multiple cardiac TFs (profiled via chromatin accessibility) | Most cis-regulatory elements (CREs) lack sequence conservation; synteny-based algorithms can identify functionally conserved CREs with diverged sequences. [4] | Hahne et al., 2025 [4] |

A critical insight from these studies is the distinction between sequence conservation and functional conservation. While many functional binding sites show clear sequence alignment across species, a significant fraction do not, yet retain their regulatory function, a concept highlighted by the "indirectly conserved" elements identified through synteny [4]. Furthermore, the binding sites that are conserved across multiple species are often of high biological importance, being enriched near genes involved in essential tissue-specific pathways and disease-associated loci from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [3].

Core Experimental Protocol for Multi-Species ChIP-seq

A standardized workflow is essential for generating comparable data across species. The following diagram and detailed protocol outline the key steps.

Diagram 1: Multi-species ChIP-seq workflow. The wet-lab steps (yellow) generate sequencing data, while the bioinformatics steps (green) analyze conservation.

Detailed Experimental Methodology

The standard protocol, as applied in studies of liver TFs across five mammals, involves several critical stages [3] [41]:

Tissue Collection and Homogenization: The process begins with the collection of homologous tissues (e.g., liver) from healthy adult individuals of each species. The liver is a preferred model for such studies due to its relative cellular homogeneity, with approximately 75% of nuclei originating from hepatocytes [3]. Tissues are processed immediately, often using perfusion to remove blood cells, and then homogenized.

Cross-linking and Chromatin Preparation: Tissues or isolated nuclei are cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde to fix protein-DNA interactions. Chromatin is then sheared into fragments of 200–500 base pairs using sonication. The efficiency of shearing is verified by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP): The sheared chromatin is incubated with a TF-specific antibody that has been raised against a conserved epitope and validated for cross-reactivity in the studied species [3] [41]. For example, the five-mammal study used antibodies against HNF4A, CEBPA, ONECUT1, and FOXA1. Antibody-bound complexes are pulled down using Protein A/G beads. After rigorous washing, the cross-linking is reversed, and the immunoprecipitated DNA is purified.

Library Preparation and Sequencing: The purified DNA is used to construct sequencing libraries, which are then subjected to high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq). The depth of sequencing must be sufficient for robust peak calling; studies often aim for tens of millions of reads per sample.

Cross-Species Bioinformatics Analysis

The computational analysis of multi-species ChIP-seq data involves several specialized steps [3] [42]:

- Peak Calling: TF binding events (peaks) are identified in each species individually using tools like MACS2 [42] or multiGPS [18]. A common practice is to use the top 500-1000 peaks for subsequent motif discovery.

- Motif Analysis: The sequences under the peak summits are analyzed with tools like MEME-ChIP to identify the enriched DNA binding motif for the TF in each species [42]. This confirms that the orthologous TFs recognize a similar motif across species [3].

- Orthology Mapping: To determine if a binding event is conserved, peaks from one species (e.g., mouse) are mapped to the genome of another (e.g., human) using tools like LiftOver [4] [41]. This relies on whole-genome alignments but has limitations for highly divergent sequences.

- Defining Conservation: A binding event is typically considered "shared" or "conserved" if a peak is called in the orthologous region of another species. Studies often use a threshold, such as requiring the peak summit to be within a few hundred base pairs of the aligned position [3].

Advanced Computational & Machine Learning Approaches

Given the limitations of alignment-based methods, new computational strategies are being developed to predict and analyze TF binding conservation. The diagram below illustrates the architecture of one such advanced approach.

Diagram 2: Domain adaptation for cross-species prediction. Frameworks like MORALE align sequence embeddings across species to create invariant features for robust binding prediction.

Key Methodologies and Performance

- Domain Adaptation (MORALE): This framework improves cross-species TF binding prediction by aligning the statistical moments (mean, variance) of sequence embeddings from different species. This encourages the model to learn species-invariant features without needing adversarial training. In benchmarks, MORALE outperformed both baseline and adversarial approaches across all tested TFs [18].

- Synteny-Based Algorithms (IPP): For distantly related species where sequence alignment fails, the Interspecies Point Projection (IPP) algorithm uses synteny (conserved gene order) and bridged alignments through multiple species to project genomic coordinates. This method identified up to five times more orthologous cis-regulatory elements between mouse and chicken than alignment-based methods [4].

- Virtual ChIP-seq: This method predicts TF binding in a new cell type or context by integrating learned associations with gene expression, existing TF binding data from other cell types, and chromatin accessibility data (e.g., ATAC-seq). This approach successfully predicted binding for 36 chromatin factors (including non-sequence-specific TFs) with high accuracy (Matthews Correlation Coefficient > 0.3) [43].

Successful execution of a multi-species ChIP-seq study relies on a suite of carefully selected reagents and tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Species ChIP-seq

| Reagent / Resource | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Cross-Reactive Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of the target TF from different species. | Must target a conserved protein epitope. Performance requires validation via ChIP in each species [3] [41]. |

| multiGPS / MACS2 | Peak-calling software to identify TF binding sites from ChIP-seq data. | multiGPS is noted for its use in processing multi-species data and handling replicates [18]. |

| MEME-ChIP | Discovers de novo and refines DNA binding motifs from ChIP-seq peak sequences. | Used to confirm motif conservation across species [3] [42]. |

| LiftOver / Interspecies Point Projection (IPP) | Maps genomic coordinates from one species to another. | LiftOver uses sequence alignment; IPP uses synteny and is more powerful for distant species [4]. |