Evaluating Metagenomic Functional Prediction Tools: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Applications

This comprehensive review examines the current landscape of computational tools for predicting functional profiles from metagenomic data, addressing critical needs for researchers and drug development professionals.

Evaluating Metagenomic Functional Prediction Tools: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines the current landscape of computational tools for predicting functional profiles from metagenomic data, addressing critical needs for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore foundational concepts in functional metagenomics, from 16S rRNA-based prediction to deep learning approaches, and evaluate methodologies across diverse sequencing technologies including short-read, long-read, and multi-omics integration. The article provides practical troubleshooting guidance for computational challenges and data interpretation, while establishing robust validation frameworks for tool comparison. By synthesizing recent advances in machine learning, explainable AI, and benchmark initiatives, this review serves as an essential resource for selecting appropriate functional prediction strategies and translating microbial functional insights into biomedical discoveries.

Foundations of Functional Metagenomics: From 16S rRNA to Deep Learning

The Evolution from Taxonomic to Functional Microbiome Analysis

The field of microbiome research has undergone a fundamental transformation, evolving from initial efforts to catalog "who is there" to sophisticated analyses of "what they are doing." This evolution from purely taxonomic profiling to functional microbiome analysis represents a critical advancement in our ability to decipher the complex roles microbial communities play in human health, disease, and ecosystem functioning. While early microbiome studies primarily relied on 16S rRNA gene sequencing to identify and quantify microbial taxa, this approach provided limited insight into the biochemical pathways, metabolic activities, and host-microbe interactions that ultimately determine microbial community function [1].

The limitations of taxonomic approaches became increasingly apparent as researchers recognized that similar microbial taxa can exhibit different functional capabilities across environments, and distinct taxa can perform similar functions in different ecosystems. This recognition, coupled with technological advancements in sequencing platforms, bioinformatics tools, and multi-omics integration, has propelled the field toward functional analysis. Next-generation sequencing technologies, particularly long-read platforms from Oxford Nanopore and PacBio, have revolutionized metagenomic assembly by generating reads spanning tens of kilobases, enabling more complete genome reconstruction and better resolution of complex genomic regions [2]. Concurrently, the development of sophisticated computational methods and machine learning approaches has empowered researchers to move beyond descriptive catalogs toward predictive models of microbiome function [3] [4].

This evolution has been particularly impactful in biomedical and pharmaceutical contexts, where understanding functional pathways is essential for identifying therapeutic targets, developing diagnostic biomarkers, and designing microbiome-based interventions. The integration of functional data with host factors is now shedding light on the mechanistic links between microbiome disturbances and conditions ranging from inflammatory bowel disease and metabolic disorders to neurodegenerative diseases [5] [6].

Methodological Evolution: From 16S rRNA to Multi-Omic Integration

Traditional Taxonomic Profiling Approaches

The foundation of microbiome analysis was built on marker-gene sequencing, primarily targeting the 16S ribosomal RNA gene in bacteria and archaea. This approach provided a cost-effective method for conducting microbial censuses across hundreds to thousands of samples simultaneously [1]. The methodology involves PCR amplification of conserved regions of the 16S gene, followed by high-throughput sequencing and classification of reads through comparison to reference databases. While this technique revolutionized our understanding of microbial diversity and community structure, it suffered from several limitations: amplification biases, insufficient resolution at the species or strain level, and an inherent inability to directly assess functional potential [1] [7].

The transition from taxonomic to functional analysis began with the recognition that inferential functional profiling from 16S data provided only partial insights. Tools like PICRUSt attempted to predict functional potential from taxonomic assignments by leveraging reference genomes, but these predictions remained approximations lacking direct genetic evidence [1]. This limitation prompted the development of more direct approaches for functional characterization that could capture the vast uncharacterized diversity of microbial communities.

Shotgun Metagenomics and Functional Annotation

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing marked a critical advancement by enabling direct assessment of the functional potential encoded in microbial communities. This approach involves sequencing random fragments of DNA from environmental samples without prior amplification, followed by computational assembly and annotation of genes and pathways [7]. The advantages over marker-gene sequencing are substantial: elimination of amplification biases, higher taxonomic resolution, and direct access to the genetic repertoire of microbial communities [1].

Shotgun metagenomics revealed the staggering functional capacity of microbiomes, with the human gut alone containing over 3.3 million non-redundant genes—far exceeding the human genome [6]. However, early metagenomic approaches faced their own challenges: short-read sequencing often fragmented complex genomic regions, while DNA extraction biases skewed taxonomic profiles toward abundant species [6]. Functional insights remained limited by reference databases, with homology-based predictions failing to characterize a significant proportion of microbial genes.

Enhanced Metagenomic Strategies

Recent technological innovations have substantially advanced functional microbiome analysis through several key approaches:

Table 1: Enhanced Metagenomic Strategies for Functional Analysis

| Strategy | Key Features | Functional Insights Enabled |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Read Sequencing (Oxford Nanopore, PacBio) | Reads spanning thousands of base pairs; resolves repetitive elements and structural variations | Complete assembly of microbial genomes from complex samples; characterization of mobile genetic elements and gene clusters [2] |

| Single-Cell Metagenomics | Isolation and sequencing of individual microbial cells | Genomic blueprints of uncultured taxa; reveals functional capacity of rare community members [6] |

| Machine Learning Integration | Random Forest, SHAP, and other ML algorithms applied to large-scale microbiome datasets | Identification of robust microbial features associated with diseases; improved classification models [5] [3] |

| Multi-Omic Integration | Combined analysis of metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics, and metabolomics | Correlation of genetic potential with functional activity; understanding of post-transcriptional regulation [4] |

The emergence of long-read sequencing technologies has been particularly transformative for functional analysis. Platforms such as Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) generate reads spanning thousands to tens of thousands of base pairs, enabling complete assembly of genes, operons, and biosynthetic gene clusters [2]. This capability has proven invaluable for studying mobile genetic elements like plasmids and transposons, which facilitate horizontal gene transfer of antibiotic resistance genes and virulence factors [2] [6]. Recent advancements have further improved the accuracy of these platforms, with PacBio's HiFi reads now achieving accuracy surpassing Q30 (99.9% accuracy) and ONT's latest chemistry generating data with ≥Q20 accuracy (99% accuracy) [2].

The integration of machine learning (ML) has addressed critical challenges in functional microbiome analysis, particularly the high-dimensional, sparse, and compositional nature of microbiome data [3]. ML approaches have been successfully applied to differentiate functional profiles between health and disease states, predict protein functions, and identify key metabolic pathways driving microbial community dynamics. For instance, a large-scale meta-analysis of Parkinson's disease microbiome studies applied ML models to 4,489 samples across 22 case-control studies, demonstrating that microbiome-based classifiers could distinguish PD patients from controls with reasonable accuracy, though model generalizability across studies remained challenging [5].

Advanced Functional Prediction Tools and Databases

Computational Frameworks for Functional Analysis

The expansion of functional microbiome analysis has been enabled by sophisticated computational frameworks that extract biological insights from complex metagenomic data. These tools address the unique challenges of microbiome data: high dimensionality, sparsity, compositionality, and technical variability [1].

BioBakery represents one of the most comprehensive computational platforms for functional microbiome analysis, incorporating tools for quality control (KneadData), taxonomic profiling (MetaPhlAn), and functional profiling (HUMAnN) [7]. This integrated approach allows researchers to move from raw sequencing data to annotated metabolic pathways in a standardized workflow, facilitating cross-study comparisons. The HUMAnN pipeline specifically enables quantification of microbial pathways in metagenomic data, connecting community gene content to biochemical functions that can be related to host physiology [7].

For predicting functions of the vast "dark matter" of uncharacterized microbial proteins, innovative methods like FUGAsseM (Function predictor of Uncharacterized Gene products by Assessing high-dimensional community data in Microbiomes) have been developed. This approach uses a two-layered random forest classifier system that integrates multiple types of community-wide evidence, including co-expression patterns from metatranscriptomes, genomic proximity, sequence similarity, and domain-domain interactions [4]. When applied to the Integrative Human Microbiome Project (HMP2/iHMP) dataset, FUGAsseM successfully predicted high-confidence functions for >443,000 protein families, including >27,000 families with weak homology to known proteins and >6,000 families without any detectable homology [4].

The accuracy of functional prediction depends heavily on comprehensive reference databases that link genetic features to biological functions. Several recently developed resources have significantly expanded our capacity for functional annotation:

Table 2: Key Databases for Functional Microbiome Analysis

| Database | Description | Functional Applications |

|---|---|---|

| HLRMDB (Human Long-Read Microbiome Database) | Curated collection of 1,672 human microbiome datasets from long-read and hybrid sequencing; includes 18,721 metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) [8] | Strain-resolved comparative genomics; context-sensitive ecological investigations; links raw reads to assembled genomes with functional annotations |

| MetaCyc | Database of metabolic pathways and enzymes | Functional profiling of metabolic potential in microbial communities; pathway abundance quantification [7] |

| ChocoPhlAn | Pangenome database of microbial species | High-resolution taxonomic and functional profiling; reference for mapping metagenomic reads [7] |

| MGnify | Comprehensive repository of microbiome sequencing data | Pre-training for transfer learning approaches; large-scale comparative functional analyses [3] |

The HLRMDB database exemplifies the evolution toward more curated, high-quality resources for functional analysis. By aggregating and standardizing long-read metagenomes across 39 sampling contexts and 42 host health states, HLRMDB provides a harmonized repository that supports reproducible, strain-resolved functional investigations [8]. The database includes >98 Gb of assembled contigs and 18,721 metagenome-assembled genomes spanning 21 phyla and 1,323 bacterial species, with extensive gene-centric functional profiles and antimicrobial resistance annotations [8].

Machine Learning and Explainable AI in Functional Prediction

Machine learning has become indispensable for functional prediction, particularly for handling the scale and complexity of microbiome data. Random Forest classifiers have demonstrated particular utility in microbiome studies due to their robustness to noisy data and ability to handle high-dimensional feature spaces [5] [4]. However, the "black box" nature of many ML algorithms has raised concerns in biological contexts where interpretability is crucial.

The emerging field of Explainable AI (XAI) addresses this limitation through techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations), which help illuminate the reasoning behind model predictions [3]. These approaches identify which microbial features (taxa, genes, or pathways) most strongly influence functional classifications, enabling researchers to generate biologically testable hypotheses from ML models.

The implementation of ML in functional analysis follows a structured workflow that begins with feature engineering to address data sparsity, proceeds through model training with appropriate validation strategies, and culminates in explanation of predictive features:

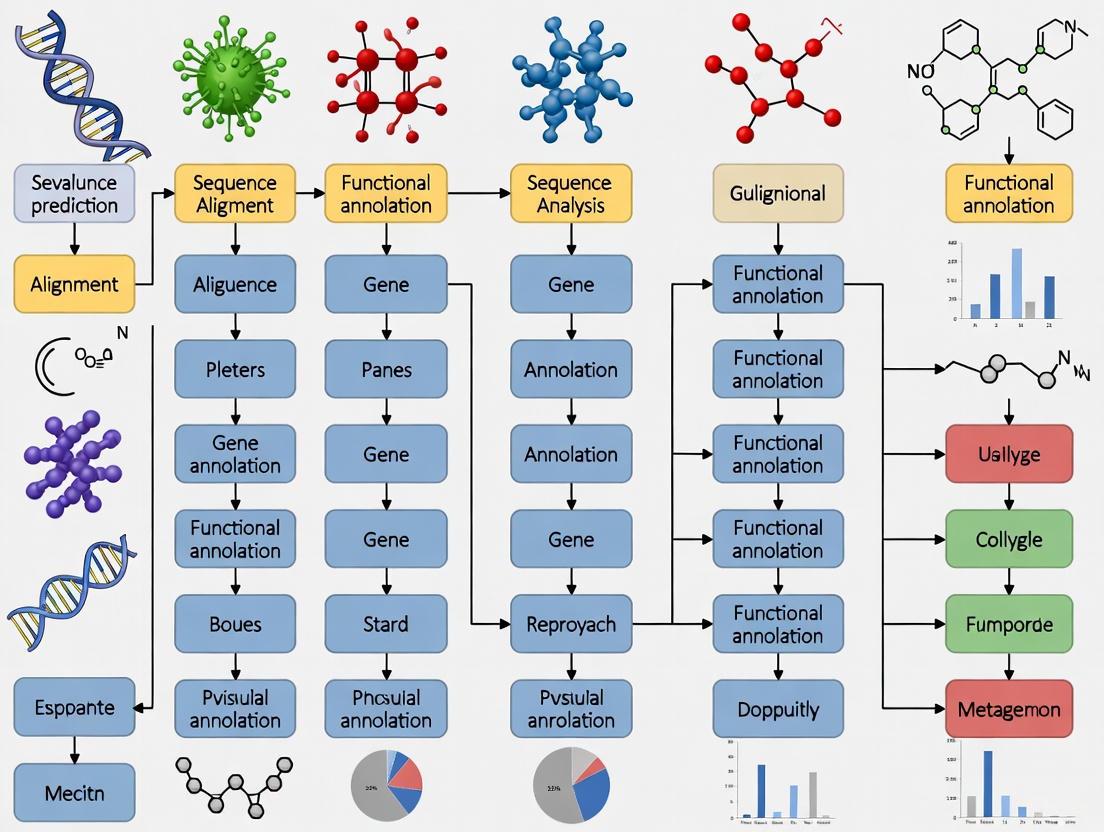

Figure 1: Machine Learning Workflow for Functional Prediction. This workflow illustrates the structured process for applying machine learning to functional microbiome data, from initial processing through model explanation.

Experimental Design and Benchmarking Best Practices

Standardized Protocols for Functional Metagenomics

Robust functional microbiome analysis requires careful experimental design and standardized protocols to minimize technical artifacts and ensure reproducible results. Key considerations include:

DNA Extraction and Library Preparation: The choice of DNA extraction method significantly impacts functional profiling results, with different protocols exhibiting biases toward specific microbial groups [1] [6]. Consistent use of validated protocols, such as the DNeasy 96 Powersoil Pro QIAcube HT Kit used in vulvar microbiome studies [7], improves cross-study comparability. For functional prediction from metatranscriptomic data, RNA stabilization and careful handling are critical to preserve labile mRNA transcripts.

Sequencing Platform Selection: The choice between short-read and long-read sequencing involves trade-offs between read accuracy, read length, and cost. While short-read platforms (Illumina) offer higher base-level accuracy for variant calling, long-read technologies (ONT, PacBio) provide more complete assembly of functional units like gene clusters and operons [2]. Hybrid approaches that combine both technologies can leverage the advantages of each [8].

Functional Annotation Pipelines: Standardized bioinformatic workflows ensure consistent functional annotation across studies. The bioBakery platform provides an integrated suite of tools that progresses from quality control (KneadData) through taxonomic profiling (MetaPhlAn) to functional characterization (HUMAnN) [7]. For pathway-centric analysis, HUMAnN maps metagenomic reads to a database of metabolic pathways (e.g., MetaCyc) to quantify pathway abundance and activity.

Benchmarking and Validation Strategies

Given the rapid development of new tools for functional analysis, rigorous benchmarking is essential to assess their performance under realistic conditions. Best practices for benchmarking include:

Use of Mock Communities: Defined mixtures of microbial species with known genomic content provide ground truth for evaluating taxonomic and functional profiling accuracy [1]. The ZymoBIOMICS Gut Microbiome Standard has been particularly valuable for assessing tool performance [2].

Cross-Validation Approaches: For machine learning applications, appropriate validation strategies are critical to avoid overfitting. Leave-One-Study-Out (LOSO) cross-validation provides a stringent test of model generalizability across different populations and experimental conditions [5]. Studies have shown that models trained on multiple datasets generalize better than those trained on individual studies [5].

Multi-Metric Assessment: Comprehensive benchmarking should evaluate multiple performance dimensions including accuracy, computational efficiency, scalability, and usability. For functional prediction tools, important metrics include sensitivity (recall), precision, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), and functional diversity captured [1].

Community-led benchmarking initiatives like the Critical Assessment of Metagenome Interpretation (CAMI) provide standardized frameworks for objectively evaluating functional prediction tools using realistic datasets [3]. These efforts help establish performance benchmarks and guide tool selection for specific research applications.

Applications in Disease Research and Therapeutic Development

Functional Insights into Disease Mechanisms

The transition to functional microbiome analysis has yielded profound insights into disease mechanisms across a wide range of conditions:

Neurodegenerative Diseases: Large-scale meta-analyses of the gut microbiome in Parkinson's disease (PD) have identified characteristic functional alterations beyond taxonomic shifts. Shotgun metagenomic studies have delineated PD-associated microbial pathways that potentially contribute to gut health deterioration and favor the translocation of pathogenic molecules along the gut-brain axis [5]. Strikingly, microbial pathways for solvent and pesticide biotransformation are enriched in PD, aligning with epidemiological evidence that exposure to these molecules increases PD risk and raising the question of whether gut microbes modulate their toxicity [5].

Infectious Diseases: Functional analysis of the gut microbiome in COVID-19 patients has revealed specific metabolic pathways involved in immune response and anti-inflammatory properties. Metataxonomic and functional profiling demonstrated that severe COVID-19 symptoms were associated with increased abundance of the genus Blautia, with functional analyses highlighting alterations in metabolic pathways that mediate immune function [9].

Inflammatory Conditions: Research on the vulvar microbiome using shotgun metagenomics has identified functional alterations associated with vulvar diseases such as lichen sclerosus (LS) and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL). Beyond taxonomic changes, these conditions exhibit altered functional capacity for specific metabolic pathways including the L-histidine degradation pathway, suggesting potential mechanistic links between microbial metabolism and disease pathology [7].

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications

Functional microbiome analysis is increasingly being translated into clinical applications:

Biomarker Discovery: Machine learning approaches applied to functional microbiome data have shown promise for developing diagnostic classifiers. In Parkinson's disease, microbiome-based machine learning models can classify patients with an average AUC of 71.9% within studies, though cross-study generalizability remains challenging (average AUC 61%) [5]. Integration of multiple datasets improves model generalizability (average LOSO AUC 68%) and disease specificity against other neurodegenerative conditions [5].

Therapeutic Target Identification: Functional analysis enables identification of specific microbial pathways that could be targeted therapeutically. For example, the discovery of enriched solvent biotransformation pathways in Parkinson's disease suggests potential interventions aimed at modulating these microbial metabolic activities [5]. Similarly, functional characterization of vulvar microbiome alterations in LS and HSIL identifies targets for developing microbiome-based vulvar therapies [7].

Drug Development Support: Understanding microbial functions involved in drug metabolism is increasingly important for pharmaceutical development. The human gut microbiome encodes a vast repertoire of enzymes that can metabolize drugs, altering their efficacy and toxicity [6]. Functional microbiome analysis can identify these microbial metabolic capabilities, informing drug design and personalized treatment strategies.

The relationship between microbial functions and host physiology reveals complex interactions that can be leveraged for therapeutic benefit:

Figure 2: Functional Interfaces Between Microbiome and Host. This diagram illustrates how specific microbial functions influence host physiology through metabolic outputs and signaling pathways.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Functional Microbiome Analysis

| Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | DNeasy 96 Powersoil Pro QIAcube HT Kit [7] | Standardized microbial DNA isolation with minimal bias |

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina DNA Prep, Oxford Nanopore Ligation Sequencing Kits | Preparation of sequencing libraries from metagenomic DNA |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, Oxford Nanopore PromethION, PacBio Revio [2] | High-throughput sequencing for metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analysis |

| Reference Materials | ZymoBIOMICS Gut Microbiome Standard [2] | Mock community for quality control and method validation |

| Storage Solutions | Zymo DNA/RNA Shield Collection Tubes [7] | Preservation of nucleic acids from field collection to processing |

Computational Tools and Databases

Table 4: Computational Tools for Functional Microbiome Analysis

| Tool Category | Representative Tools | Key Function |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | KneadData, FastQC [7] | Removal of low-quality sequences and host contamination |

| Taxonomic Profiling | MetaPhlAn, Kraken2 [7] | Species-level identification and quantification |

| Functional Profiling | HUMAnN, FUGAsseM [4] [7] | Pathway abundance quantification and protein function prediction |

| Assembly/Binning | metaFlye, HiFiasm-meta, BASALT [2] | Reconstruction of genomes from complex metagenomes |

| Machine Learning | SIAMCAT, BioAutoML [5] [3] | Classification models and feature selection for biomarker discovery |

The evolution from taxonomic to functional microbiome analysis represents a paradigm shift that is transforming our understanding of microbial communities and their interactions with hosts and environments. This transition has been driven by synergistic advancements in sequencing technologies, computational tools, and analytical frameworks that enable researchers to move beyond descriptive catalogs toward mechanistic insights.

Several emerging trends are likely to shape the future of functional microbiome analysis. The integration of multi-omic data (metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics, and metabolomics) will provide increasingly comprehensive views of microbial community function, capturing the dynamic interplay between genetic potential and functional activity [4] [6]. Long-read sequencing technologies will continue to improve in accuracy and throughput, enabling more complete reconstruction of functional elements like biosynthetic gene clusters and mobile genetic elements [2] [8]. Machine learning and artificial intelligence will play an expanding role in functional prediction, with approaches like transfer learning and deep learning enabling more accurate annotation of uncharacterized proteins [3] [4].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advancements offer unprecedented opportunities to decipher the functional mechanisms linking microbiomes to health and disease. The continued development of standardized protocols, benchmarking resources, and shared databases will be critical for translating these opportunities into robust, reproducible discoveries with clinical applications [1]. As functional prediction tools become more sophisticated and accessible, they will increasingly support the development of microbiome-based diagnostics, therapeutics, and personalized health interventions.

The evolution from taxonomic to functional analysis thus represents not merely a technical progression, but a fundamental transformation in how we conceptualize, investigate, and ultimately harness the functional potential of microbial communities for improving human health and managing disease.

The transition from traditional homology-based methods to artificial intelligence (AI)-driven prediction represents a paradigm shift in metagenomics. This evolution is driven by the fundamental need to decipher the functional potential of complex microbial communities, moving beyond mere taxonomic cataloging to understanding the biochemical processes they enact. Early metagenomic analyses were heavily reliant on reference genomes, leaving a significant portion of microbial genes—often from novel or uncultivated species—functionally uncharacterized. Homology-based methods, which infer function based on sequence similarity to experimentally characterized proteins, have been the cornerstone of bioinformatics. However, their reliance on existing databases renders them ineffective for the vast "microbial dark matter" lacking known homologs. The advent of AI, particularly deep learning, has begun to illuminate this dark matter by enabling the prediction of protein function from sequence alone, learning complex patterns that elude traditional similarity metrics. This guide objectively compares the performance, underlying protocols, and practical applications of these core computational approaches within the context of modern metagenomic research [10] [11].

Comparative Analysis of Computational Approaches

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and limitations of the primary functional prediction strategies used in metagenomics.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Functional Prediction Approaches for Metagenomics

| Approach | Core Methodology | Key Tools | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homology-Based | Uses sequence alignment (e.g., BLAST) to find statistically significant matches to proteins of known function in databases. | DIAMOND, BLAST, MG-RAST [12] [11] | High accuracy for proteins with close homologs; well-established and easy to interpret. | Fails for novel proteins without database homologs; database bias toward well-studied organisms; computationally intensive. |

| Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) | Employs probabilistic models (profile HMMs) of multiple sequence alignments from protein families to detect distant homologs. | Pfam, TIGRFAM, antiSMASH [13] [12] | More sensitive than pairwise alignment for detecting evolutionarily distant relationships; excellent for identifying protein domains and families. | Still reliant on curated multiple sequence alignments; limited to known protein families; can miss entirely novel folds or functions. |

| Machine Learning (ML) / Deep Learning (DL) | Uses algorithms trained on sequence and functional data to learn complex patterns and predict function without explicit homology. | DeepGOMeta, DeepFRI, SPROF-GO, TALE, NetGO 3.0 [12] [11] | Capable of annotating novel proteins with no known homologs; can capture complex sequence-function relationships; high throughput. | Requires large, high-quality training datasets; "black box" nature can reduce interpretability; performance depends on training data representativeness. |

Experimental Benchmarking and Performance Data

Independent evaluations and controlled benchmarks are crucial for assessing the real-world performance of these tools. Below is a summary of quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of Selected Prediction Tools

| Tool / Approach | Methodology | Key Performance Findings | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepGOMeta | DL model using ESM2 protein embeddings, trained on prokaryotic, archaeal, and phage proteins. | Achieved a weighted average clustering purity (WACP) of 0.89 on WGS data, outperforming PICRUSt2 (WACP 0.72) in grouping samples by phenotype based on function [11]. | Evaluation on four diverse microbiome datasets with paired 16S and WGS data, using clustering purity against known phenotype labels as the metric [11]. |

| Kraken2/Bracken | K-mer based taxonomic classification for identifying community members. | Achieved an F1-score of 0.96 for detecting Listeria monocytogenes in a milk product metagenome, correctly identifying pathogens at abundances as low as 0.01% [14]. | Benchmarking against other classifiers (MetaPhlAn4, Centrifuge) using simulated metagenomes with defined pathogen abundances [14]. |

| Homology (DIAMOND) | Sequence similarity-based functional annotation. | Served as a baseline in DeepGOMeta evaluation; performance is limited on proteins without similar sequences in reference databases [11]. | Used for functional annotation of predicted protein sequences from metagenomic assemblies. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Benchmarking Functional Predictors

The following workflow outlines a standardized protocol for benchmarking functional prediction tools, as employed in recent studies [11]:

1. Dataset Curation:

- Source: Obtain paired 16S rRNA amplicon and Whole-Genome Shotgun (WGS) sequencing data from public repositories (e.g., PRJNA397112, PRJEB27005).

- Selection Criteria: Select datasets that represent diverse microbial habitats (e.g., human gut, environmental soil) and include sample-level metadata with known phenotypes (e.g., disease state, health status).

2. Data Pre-processing:

- WGS Data: Trim raw reads for quality and remove adapter sequences using fastp. For host-associated samples, filter out host-derived reads using Bowtie2 aligned against the host reference genome.

- 16S Data: Process raw amplicon sequences using a standardized pipeline (e.g., a Nextflow pipeline with the RDP classifier) to generate taxonomic abundance profiles.

3. Metagenome Assembly and Gene Prediction:

- Assemble quality-filtered WGS reads into contigs using a metagenomic assembler like MEGAHIT.

- Predict open reading frames (ORFs) and protein sequences from the assembled contigs using Prodigal.

4. Functional Annotation:

- Annotate the predicted protein sequences using the tools being benchmarked (e.g., DeepGOMeta for DL, DIAMOND for homology-based, and PICRUSt2 for 16S-based inference).

- For each tool, generate a functional profile for each sample. This can be a binary (presence/absence) or an abundance-weighted matrix of Gene Ontology terms or metabolic pathways.

5. Performance Evaluation:

- Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and k-means clustering to the generated functional profiles.

- Set the number of clusters (k) based on the number of known phenotype categories in the metadata.

- Calculate the Weighted Average Clustering Purity (WACP) to quantify how well the functionally derived clusters match the true, biologically defined sample groupings. The formula is:

Weighted Average Purity = (1/N) * Σ (max_{j} |c_i ∩ t_j|)whereNis the total number of samples,c_iis a cluster, andt_jis a phenotype category [11].

Successful metagenomic analysis relies on a suite of computational "reagents" – databases, software, and reference standards.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomic Analysis

| Resource | Type | Primary Function in Analysis | Relevance to Functional Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot [11] | Protein Database | Repository of manually annotated, experimentally characterized protein sequences. | Serves as the gold-standard training data and reference for homology-based methods and AI model training. |

| Gene Ontology (GO) [11] | Ontology Database | Provides a standardized, hierarchical vocabulary for protein functions (Molecular Function, Biological Process, Cellular Component). | The common output framework for functional prediction tools, allowing for consistent comparison and interpretation of results. |

| STRING Database [11] | Protein-Protein Interaction Network | Documents known and predicted protein-protein interactions. | Can be integrated with AI models (e.g., DeepGOMeta) to improve functional inference using network context. |

| RDP Database [11] | Taxonomic Reference | Provides a curated database of 16S rRNA sequences for taxonomic classification. | Enables 16S-based profiling and functional inference via tools like PICRUSt2, serving as a baseline for WGS-based methods. |

| HUMAnN 3.0 [11] | Bioinformatic Pipeline | Quantifies the abundance of microbial metabolic pathways from metagenomic sequencing data. | A key tool for downstream functional analysis, converting gene-level predictions into system-level metabolic insights. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Gut Microbe Standard | Mock Microbial Community | A defined mix of microbial cells with known composition, used as a positive control. | Enables validation and calibration of entire workflows, from DNA extraction to sequencing and bioinformatic analysis [2]. |

Logical Workflow for Selecting a Functional Prediction Strategy

The choice of tool depends heavily on the research question, data type, and resources. The following diagram outlines a logical decision-making process.

The landscape of functional prediction in metagenomics is no longer dominated by a single methodology. Homology-based approaches remain powerful and reliable for annotating genes with known relatives, providing a foundation of validated functional hypotheses. However, the emergence of AI-driven tools like DeepGOMeta marks a critical advancement, offering the ability to probe the functional unknown and generate biologically meaningful insights from novel sequences. Benchmarking studies demonstrate that these deep learning models can outperform traditional methods in key tasks, such as phenotypically relevant clustering based on functional profiles. For researchers and drug development professionals, the optimal strategy often involves a hybrid approach: leveraging AI for comprehensive, de novo functional discovery and using homology-based methods for validation and detailed characterization of specific, high-interest targets. This combined toolkit is paving the way for a more complete and mechanistic understanding of the microbiome's role in health, disease, and biotechnology.

Metagenomics has revolutionized our understanding of microbial communities, enabling researchers to investigate the genetic material of microorganisms directly from their natural environments without the need for cultivation. The choice of sequencing technology—short-read (SR) or long-read (LR)—fundamentally shapes the scope, resolution, and outcomes of metagenomic studies. Within the broader context of evaluating functional prediction tools for metagenomics research, this comparison guide objectively assesses the performance of these competing sequencing platforms. The insights provided here will aid researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate technology for their specific applications, particularly in areas such as taxonomic classification, functional annotation, and the recovery of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) [15].

Performance Comparison at a Glance

The following tables summarize key performance metrics and characteristics for short-read and long-read metagenomic sequencing technologies, based on recent experimental and benchmarking studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Sequencing Technologies

| Performance Metric | Short-Read (e.g., Illumina) | Long-Read (e.g., PacBio, ONT) |

|---|---|---|

| Per-Base Accuracy | >99.9% (Q30) [16] | ~99.9% (PacBio HiFi Q30), ~99% (ONT R10+) [16] [2] |

| Typical Read Length | 75-300 bp [16] | 5,000-25,000+ bp [16] [17] |

| Sensitivity in LRTI Diagnosis | 71.8% (Average across studies) [16] | 71.9% (Nanopore average) [16] |

| Assembly Contiguity | Fragmented assemblies; struggles with repeats [18] [2] | More contiguous assemblies; resolves repeats [18] [2] |

| MAG Recovery (Number & Quality) | Lower recovery of near-complete MAGs [19] | Up to 186% more single-contig MAGs recovered [17] |

| Recovery of Variable Regions | Underestimates diversity in viral, defense regions [18] | Improved recovery of variable genome regions [18] |

Table 2: Comparative Strengths, Challenges, and Ideal Use Cases

| Aspect | Short-Read Sequencing | Long-Read Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Key Strengths | Cost-effective for high coverage [20]; High per-base accuracy [16]; Low DNA input requirement [18] | Resolves complex regions (repeats, SVs) [18] [2]; Improves MAG quality [21] [17]; Better detection of MGEs and BGCs [2] |

| Main Challenges | Misses complex genomic regions [18]; Limited strain resolution [2]; Lower contiguity of assemblies [21] | Higher initial cost; Historically higher error rates (now improved) [16]; Requires higher DNA quality/quantity [18] |

| Ideal Applications | High-throughput diversity profiling [15]; Studies with limited DNA [18]; Projects with budget constraints | Assembling complete genomes [2]; Studying structural variation & horizontal gene transfer [2]; Identifying novel genes & pathways [21] |

Experimental Insights and Methodologies

Direct comparisons of SR and LR sequencing using real and simulated datasets reveal how these technologies perform in practice for metagenomic analysis.

Assembly Completeness and MAG Recovery

A benchmark of metagenomic binning tools on real datasets demonstrated that multi-sample binning with long-read data substantially improves the recovery of high-quality MAGs. In a marine dataset with 30 samples, multi-sample binning of long-read data recovered 50% more medium-quality MAGs and 55% more near-complete MAGs compared to single-sample binning [19]. For assembly-focused studies, PacBio HiFi sequencing, when processed with specific pipelines like hifiasm-meta and HiFi-MAG-Pipeline v2.0, can generate up to 186% more single-contig MAGs than a single binning strategy with MetaBat2 [17]. This leap in assembly quality is crucial for exploring the vast diversity of unculturable microorganisms.

Analysis of Complex Genomic Regions

LR sequencing excels at recovering genomic segments that are problematic for SR platforms. A study on a natural soil community used paired LR and SR data to investigate specific factors leading to misassemblies. The research identified that low coverage and high sequence diversity are the primary drivers of SR assembly failure. Consequently, SR metagenomes tend to "miss" variable parts of the genome, such as integrated viruses or defense system islands, potentially underestimating the true diversity of these elements. LR sequencing was shown to complement SR data by improving both assembly contiguity and the recovery of these variable regions [18]. This capability also extends to profiling mobile genetic elements (MGEs), antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), and biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) [2].

Functional and Taxonomic Profiling

A systematic review comparing LR and SR for diagnosing lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) found that while the average sensitivity was similar for Illumina (71.8%) and Nanopore (71.9%), their specific strengths differed [16]. Illumina consistently provided superior genome coverage, often approaching 100%, which is optimal for applications requiring maximal accuracy. In contrast, Nanopore demonstrated superior sensitivity for detecting Mycobacterium species and offered faster turnaround times, making it suitable for rapid pathogen detection [16]. Furthermore, because HiFi reads are long enough to span an average of eight genes, tools like the Diamond + MEGAN-LR pipeline can assign taxonomic classification and functional annotations simultaneously from the same reads [17].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for benchmarking, this section outlines key methodologies from cited studies.

Protocol 1: Comparative Analysis of SR and LR Assembly

This protocol is adapted from a study that used paired LR and SR sequences from a soil microbiome to identify factors impacting genome assembly [18].

Step 1: Data Generation and Assembly

- Generate PacBio HiFi long-reads and Illumina HiSeq short-reads from the same sample.

- Perform LR assembly using

metaFlye(v2.4.2) with the-metaflag and an estimated genome size. - Perform SR assembly using

MEGAHIT(v1.1.3) andmetaSPAdes(v3.15.3) on quality-trimmed reads.

Step 2: Processing of LR Contigs

- Split the LR-assembled contigs into 1 kb subsequences using

seqkit(v2.6.1) with a 500-bp sliding window. - Filter subsequences by read-mapping raw SRs to them with

bowtie2(v2.3.5), retaining only subsequences with at least 1x coverage over 80% of their length.

- Split the LR-assembled contigs into 1 kb subsequences using

Step 3: Assessing SR Assembly Recovery

- Compare assembled contigs from both SR assemblers to the filtered LR subsequence reference set using

BLAST(v2.14.0+; blastn, >99% identity). - For each subsequence, calculate "percent recovery" as the length of the best BLAST hit divided by the total subsequence length (1 kb).

- Label subsequences as "fully assembled" (100% recovery in at least one SR assembly) or "not fully assembled."

- Compare assembled contigs from both SR assemblers to the filtered LR subsequence reference set using

Step 4: Gene Enrichment Analysis

- Annotate genes on the LR assembly using a platform like IMG.

- Use Fisher's exact test to identify COG categories enriched in "fully assembled" versus "not fully assembled" subsequences, with FDR correction for P-values.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Binning Performance Across Data Types

This protocol is based on a comprehensive benchmark of 13 metagenomic binning tools [19].

Step 1: Data Preparation and Assembly

- Collect multiple metagenomic samples from the same environment (e.g., human gut, marine).

- Generate three types of data for the samples: Illumina short-reads, PacBio HiFi long-reads, and Oxford Nanopore long-reads.

- Perform co-assembly and/or individual sample assembly for each data type using appropriate assemblers.

Step 2: Binning Execution

- Run multiple binning tools (e.g., COMEBin, MetaBAT 2, SemiBin2, VAMB) under three different modes:

- Co-assembly binning: Assemble all samples together, then bin.

- Single-sample binning: Assemble and bin each sample independently.

- Multi-sample binning: Assemble samples individually but use cross-sample coverage information for binning.

- Run multiple binning tools (e.g., COMEBin, MetaBAT 2, SemiBin2, VAMB) under three different modes:

Step 3: MAG Quality Assessment

- Assess the quality of all recovered MAGs using

CheckM 2. - Define quality tiers:

- Medium-quality (MQ): Completeness > 50%, Contamination < 10%

- Near-complete (NC): Completeness > 90%, Contamination < 5%

- High-quality (HQ): Completeness > 90%, Contamination < 5%, and contains 5S, 16S, 23S rRNA genes and ≥ 18 tRNAs.

- Assess the quality of all recovered MAGs using

Step 4: Downstream Functional Annotation

- Annotate antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) on the non-redundant, high-quality MAGs.

- Compare the number of potential ARG hosts and BGC-containing strains identified by different data-binning combinations.

Visual Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical relationships and experimental workflows described in this guide.

Technology Selection Framework

Comparative Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details key reagents, software, and reference materials essential for conducting robust metagenomic comparative studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Type | Function/Application | Example Sources / Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Shield | Reagent | Preserves microbial community composition and DNA fragment length post-sampling for LR sequencing [17]. | Zymo Research |

| Microbiome Standards | Reference Material | Enables benchmarking and detection of biases in extraction, library prep, and bioinformatics [17]. | ZymoBIOMICS Standards |

| Host DNA Removal Tools | Software | Critical for host-associated microbiome studies (e.g., human, rice) to reduce contamination and improve microbial analysis accuracy [22]. | KneadData, Bowtie2, BWA, Kraken2 |

| LR Assembly Tools | Software | Specialized assemblers for reconstructing continuous genomic sequences from long, error-prone reads. | metaFlye [18] [2], hifiasm-meta [17] |

| Binning Tools | Software | Groups assembled contigs into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) using composition and coverage. | COMEBin [19], MetaBAT 2 [19], SemiBin2 [19] |

| Taxonomic/Functional Profiler | Software | Assigns taxonomic classification and functional annotations directly from long reads. | Diamond + MEGAN-LR [17] |

| MAG Quality Checker | Software | Assesses the completeness and contamination of binned MAGs using lineage-specific marker genes. | CheckM2 [19] |

| Arformoterol | Formoterol | Formoterol is a high-potency, long-acting β2-adrenergic receptor agonist for asthma and COPD research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| Fructigenine A | Fructigenine A, MF:C27H29N3O3, MW:443.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

In metagenomics research, the accurate functional prediction of microbial communities is paramount for understanding their role in host physiology, environmental ecosystems, and disease pathogenesis. This process is heavily dependent on reference databases that map sequencing data to known biological pathways and functions. Among the most widely utilized resources are KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes), GO (Gene Ontology), and MetaCyc. These databases differ significantly in their scope, content, and underlying conceptualization of biological systems, which directly influences their performance in functional profiling workflows [23] [24]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these databases to help researchers select the most appropriate resource for their specific metagenomic studies.

Quantitative Database Comparison

The utility of a reference database is largely determined by the scale and nature of its contents. The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics for KEGG, MetaCyc, and GO, based on cross-database studies.

Table 1: Core Content and Statistical Comparison of KEGG, MetaCyc, and GO

| Feature | KEGG | MetaCyc | GO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Pathways, genomes, chemicals, diseases | Experimentally elucidated metabolic pathways and enzymes | Gene product attributes (Molecular Function, Cellular Component, Biological Process) |

| Total Pathways | 179 modules; 237 pathway maps [23] | 1,846 base pathways; 296 super pathways [23] | Not Applicable |

| Reactions | ~8,692 (approx. 6,174 in pathways) [23] | ~10,262 (approx. 6,348 in pathways) [23] | Not Applicable |

| Compounds | ~16,586 (approx. 6,912 in reactions) [23] | ~11,991 (approx. 8,891 in reactions) [23] | Not Applicable |

| Conceptualization | Larger, more generalized pathway maps; includes "map" nodes [23] [24] | Smaller, more granular base pathways; curated from experimental literature [25] [23] | Directed acyclic graph (DAG) of terms describing gene product attributes |

| Curation | Manually drawn pathway maps; mixed manual and computational curation [24] | Literature-based manual curation from experimental evidence [25] | Consortium-based manual and computational curation |

Table 2: Performance and Applicability in Metagenomic Analysis

| Aspect | KEGG | MetaCyc | GO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Use Case | Pathway mapping and module analysis; multi-omics integration | Metabolic engineering; detailed enzyme function; high-quality reference for prediction | Functional enrichment analysis of gene sets; understanding biological context beyond metabolism |

| Strengths | Broad coverage of organisms and diseases; well-integrated system; widely supported by tools | High-quality, experimentally validated reactions; fewer unbalanced reactions facilitate metabolic modeling [23] | Extremely detailed functional annotation; independent of pathway context |

| Limitations | Pathways can be overly generic; includes non-enzymatic reaction steps ("map" nodes) [23] | Smaller overall compound database; less coverage for xenobiotics and glycans [23] | Does not describe metabolic pathways directly; can be complex for new users |

Experimental Protocols for Database Evaluation

Evaluating the performance of these databases in real-world metagenomic studies requires standardized experimental protocols. The following methodologies are commonly employed in comparative analyses.

Protocol for Functional Profiling of Shotgun Metagenomic Data

This protocol is used to assess how database choice influences the functional profile derived from a metagenomic sample [26].

- Data Preprocessing: Perform quality control on raw shotgun metagenomic reads using tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic. Remove host DNA if necessary.

- Taxonomic Profiling: Use alignment-based tools like MetaPhlAn4, which relies on marker gene databases, to determine the taxonomic composition of the sample.

- Functional Profiling:

- KEGG-based: Process the quality-controlled reads with HUMAnN3, which uses the KEGG Orthology (KO) database to assign gene families and reconstruct pathway abundances.

- MetaCyc-based: Use HUMAnN3 with the MetaCyc database as the reference to generate pathway abundances.

- Data Output: The outputs are gene family counts and pathway abundance tables (stratified and unstratified) for each database.

- Downstream Analysis: Compare the resulting functional profiles through diversity analysis (alpha and beta diversity) and differential abundance analysis (e.g., using LEfSe) to identify how database choice affects the biological interpretations.

Protocol for Metabolite Annotation and Pathway Prediction

This protocol evaluates the databases' utility in annotating metabolites and predicting metabolic pathways from structural data [27] [28].

- Feature Extraction: From a set of metabolites, generate 201 features including MACCSKeys (molecular fingerprints) and physical properties from SMILES annotations using tools like RDKit and PubChem's Cactus [27].

- Data Pre-processing: Reduce the dimensionality of the feature set using Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

- Clustering and Classification:

- Apply K-mode clustering for categorical data and K-prototype clustering for mixed data types to group metabolites based on structural similarity.

- Use machine learning classifiers (e.g., AdaBoostClassifier) to correlate metabolite clusters with known pathways from KEGG, MetaCyc, and GO.

- Performance Measurement: Quantify the accuracy with which the model links known metabolites to their correct pathways in each database. Studies have reported accuracy as high as 92% for this structure-based approach [27].

- Network-Based Validation: Integrate the findings into a two-layer interactive network (data-driven and knowledge-driven) to assess annotation propagation efficiency, a method implemented in tools like MetDNA3 [28].

Reagent and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Functional Prediction

| Item/Tool Name | Function/Application | Relevance to Database Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| HUMAnN3 | Functional profiling of metagenomic data | Pipeline for quantifying pathway abundance using either KEGG or MetaCyc as a reference [26] |

| MetaPhlAn4 | Taxonomic profiling from metagenomic data | Provides species-level context for stratifying functional predictions [26] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics and SMILES analysis | Generates molecular fingerprints (e.g., MACCSKeys) from metabolite structures for pathway prediction [27] |

| Pathway Tools | Software platform for MetaCyc | Used for curation, navigation, and programmatic querying of MetaCyc; supports metabolic modeling [25] |

| MetDNA3 | Two-layer networking for metabolite annotation | Leverages integrated KEGG/MetaCyc reaction networks to annotate unknowns and propagate annotations [28] |

| clusterProfiler | R package for enrichment analysis | Performs statistical enrichment analysis of functional terms, including KEGG pathways and GO terms [24] |

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows for functional prediction and the logical relationships between the databases and their applications.

Functional Profiling Workflow for Metagenomics

Database Structure and Connectivity

The choice between KEGG, MetaCyc, and GO is not a matter of identifying a single superior database, but rather of selecting the most appropriate tool for the specific research question and analytical goal. KEGG offers a broad, systems-level view that is highly effective for genomic and multi-omics integration across a wide range of organisms. MetaCyc provides a higher level of experimental validation and granularity for metabolic pathways, making it invaluable for metabolic engineering and detailed biochemical studies. GO is indispensable for comprehensive functional enrichment analysis that extends beyond metabolism to include cellular components and biological processes.

For maximal coverage and insight, an integrative approach is often most powerful. Leveraging multiple databases, or tools like MetDNA3 that combine them into a comprehensive metabolic reaction network, can mitigate the individual limitations of each resource and provide a more robust functional prediction [28]. The experimental data and protocols outlined in this guide provide a framework for researchers to make informed decisions and critically evaluate the functional predictions generated in their metagenomic studies.

Key Technical Terms and Metrics in Functional Prediction

Functional prediction represents a crucial methodology in metagenomics that enables researchers to infer the functional capabilities of microbial communities based on their genetic material, without requiring resource-intensive shotgun metagenomic sequencing [29]. This approach bridges the gap between cost-effective 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and the comprehensive functional profiling offered by whole-genome shotgun metagenomics [30]. By leveraging phylogenetic relationships and reference genome databases, these tools predict the abundance of functional genes and metabolic pathways, allowing researchers to generate hypotheses about microbial community activities from taxonomic data alone [31]. The fundamental premise underlying these methods is that evolutionary relationships between microorganisms correlate with their functional genetic content, enabling reasonable inferences about uncharacterized taxa based on their phylogenetic position relative to reference genomes with known functional annotations [29].

The computational frameworks for functional prediction have evolved substantially, with current tools employing diverse algorithms ranging from phylogenetic placement methods to advanced machine learning approaches [15] [32]. These methods typically map observed taxonomic abundances to reference databases containing genomic information from cultured isolates and metagenome-assembled genomes, then extrapolate functional profiles based on the identified relationships [29]. The resulting functional predictions have enabled researchers to explore microbial community functions across diverse fields including human health, environmental microbiology, and biotechnology [33] [30]. However, the accuracy and applicability of these predictions vary considerably depending on the sample type, reference database completeness, and specific functional categories being examined [29].

Performance Comparison of Functional Prediction Tools

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Environments

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Functional Prediction Tools Across Sample Types

| Tool | Algorithm Type | Human Samples (Inference Correlation) | Non-Human Samples (Inference Correlation) | Reference Database | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PICRUSt | Phylogenetic inference | 0.46 (Human_KW dataset) | Significantly reduced (e.g., gorilla, chicken, soil) | Greengenes [31] | Established method with extensive historical usage |

| PICRUSt2 | Phylogenetic inference | Reasonable performance | Sharp degradation outside human samples | Genome Taxonomy Database [29] | Improved taxonomic range over PICRUSt |

| Tax4Fun | Reference-based | Robust correlation in human gut samples | Poor performance in environmental samples | SILVA SSU rRNA [29] | Optimized for human microbiome studies |

| DeepFRI | Deep learning | 70% concordance with orthology-based methods [32] | Less sensitive to taxonomic bias [32] | Gene Ontology terms [32] | High annotation coverage (99% of genes) |

| REBEAN | Language model | Demonstrates robust performance [34] | Applicable to diverse environments [34] | Enzyme Commission numbers [34] | Reference and assembly-free annotation |

Performance Across Functional Categories

Table 2: Tool Performance Variation by Functional Category

| Functional Category | Prediction Accuracy | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Housekeeping functions | Higher accuracy | Includes replication, repair, translation [29] |

| Metabolic pathways | Variable accuracy | Better for core metabolic processes [29] |

| Environment-specific functions | Lower accuracy | Poorer for genes with high phylogenetic variability [29] |

| Horizontally transferred genes | Lowest accuracy | Difficult to predict from phylogenetic position [29] |

| Novel enzymatic activities | Emerging capability | REBEAN shows promise for novel enzyme discovery [34] |

Performance evaluation of functional prediction tools must extend beyond simple correlation metrics, as strong Spearman correlations (0.53-0.87) between predicted and actual functional profiles can be misleading [29]. Even when gene abundances were permuted across samples, correlation coefficients remained high (0.84 for permuted vs. 0.85 for unpermuted in soil samples), indicating that correlation alone is an unreliable performance metric [29]. A more robust evaluation approach examines inference consistency—comparing how well predicted functions replicate statistical inferences from actual metagenomic sequencing when testing hypotheses about group differences [29].

Using this inference-based evaluation, prediction tools show reasonable performance for human microbiome samples but experience sharp degradation outside human datasets [29]. This performance pattern reflects the taxonomic bias in reference databases, which are disproportionately populated with human-associated microorganisms [29]. Furthermore, accuracy varies substantially across functional categories, with "housekeeping" functions related to genetic information processing (replication, repair, translation) showing better prediction accuracy compared to environment-specific functions [29].

Emerging approaches like DeepFRI and REBEAN demonstrate promising alternatives to traditional phylogenetic placement methods [32] [34]. DeepFRI, a deep learning-based method, achieves 70% concordance with orthology-based annotations while dramatically increasing annotation coverage to 99% of microbial genes compared to approximately 12% for conventional orthology-based approaches [32]. REBEAN utilizes a transformer-based DNA language model that can predict enzymatic functions without relying on sequence-defined homology, potentially enabling discovery of novel enzymes that evade detection by reference-dependent methods [34].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Studies

Standardized Evaluation Framework

The most comprehensive assessment of functional prediction tools employs a standardized framework that compares predictions against shotgun metagenome sequencing results across diverse sample types [29]. The experimental protocol involves:

Sample Selection and Sequencing: Researchers select multiple datasets encompassing human, non-human animal, and environmental samples with both 16S rRNA amplicon and shotgun metagenome sequencing data available [29]. This design enables direct comparison between predicted and measured functional profiles. Sample types should include human gut microbiomes (where reference databases are most complete) and environmentally-derived samples (soil, water, non-human animal guts) where database coverage is sparser [29].

Data Processing Pipeline: For each dataset, 16S rRNA sequences are processed through standard QIIME or mothur pipelines to obtain operational taxonomic units (OTUs) or amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) [29] [35]. These taxonomic profiles serve as input for functional prediction tools (PICRUSt, PICRUSt2, Tax4Fun) using their default parameters and databases [29]. Simultaneously, shotgun metagenome sequences undergo quality control, assembly, gene calling, and annotation to generate "ground truth" functional profiles [32].

Statistical Evaluation: Rather than relying solely on correlation coefficients, the protocol employs inference consistency as the primary metric [29]. For each gene, researchers calculate P-values testing differences in relative abundance between sample groups (e.g., healthy vs. diseased) using both predicted abundances and metagenome-measured abundances [29]. The correlation between these P-value profiles across all genes provides a more robust measure of functional prediction accuracy [29].

DNA Extraction and Library Preparation Methodology

Standardized DNA extraction protocols are critical for reproducible metagenomic studies [35]. Comparative studies have evaluated multiple commercial kits:

DNA Extraction Kits: The Zymo Research Quick-DNA HMW MagBead Kit demonstrates the most consistent results with minimal variation among replicates, making it suitable for long-read sequencing applications [35]. The Macherey-Nagel kit provides the highest DNA yield, while the Invitrogen kit shows moderate yields with higher variance among replicates [35]. The Qiagen kit produces the lowest yield and highest host DNA contamination in stool samples [35].

Library Preparation: The Illumina DNA Prep library construction method has been identified as particularly effective for high-quality microbial diversity analysis [35]. For 16S rRNA sequencing, the V1-V3 regions sequenced using PerkinElmer kits and V1-V2/V3-V4 regions using Zymo Research kits provide reliable taxonomic profiling [35]. For full-length 16S rRNA sequencing, Pacific Biosciences Sequel IIe and Oxford Nanopore Technologies MinION platforms enable higher taxonomic resolution, with PacBio demonstrating superior species-level classification (74.14% for long reads vs. 55.23% for short reads) [35].

Bioinformatic Processing: The minitax tool provides consistent results across sequencing platforms and methodologies, reducing variability in bioinformatics workflows [35]. For shotgun metagenome analysis, sourmash produces excellent accuracy and precision on both short-read and long-read sequencing data [35].

Workflow Visualization of Functional Prediction

Comparative Analysis Workflow

Comparative Analysis Workflow for Functional Prediction Tools

This workflow illustrates the standardized methodology for evaluating functional prediction tools against experimental data. The process begins with sample collection and DNA extraction, followed by parallel sequencing approaches [29]. The 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing data undergoes taxonomic profiling to generate OTUs or ASVs, which serve as input for functional prediction tools [29]. Simultaneously, shotgun metagenome sequencing provides the reference functional profile through gene calling and annotation [32]. Performance evaluation incorporates both correlation analysis and inference consistency testing to comprehensively assess prediction accuracy [29].

Next-Generation Prediction Approaches

Next-Generation Functional Prediction Approaches

This diagram contrasts traditional phylogenetic approaches with emerging machine learning methods for functional prediction. Traditional methods (left pathway) rely on taxonomic assignment, phylogenetic placement in reference trees, and function imputation from reference genomes with functional annotations [29]. This reference-dependent approach introduces database biases and struggles with novel microorganisms [29]. Modern machine learning approaches (right pathway) utilize foundation model training (REMME) to generate read embeddings that capture DNA sequence context, followed by task-specific fine-tuning (REBEAN) for direct function prediction without reference database dependence [34]. This reference-free approach enables discovery of novel enzymes and functions that evade detection by traditional methods [34].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Category | Specific Product/Resource | Function/Application | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Zymo Research Quick-DNA HMW MagBead Kit | High molecular weight DNA extraction | Most consistent results, minimal variation [35] |

| Macherey-Nagel Kit | High-yield DNA extraction | Highest DNA yield [35] | |

| Invitrogen Kit | Standard DNA extraction | Moderate yield, higher variance [35] | |

| Library Preparation | Illumina DNA Prep | Library construction for shotgun metagenomics | Most effective for microbial diversity analysis [35] |

| PerkinElmer V1-V3 Kit | 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing | Reliable taxonomic profiling [35] | |

| Zymo Research V1-V2/V3-V4 Kits | 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing | Alternative for taxonomic profiling [35] | |

| Sequencing Platforms | PacBio Sequel IIe | Full-length 16S rRNA sequencing | Higher species-level classification (74.14%) [35] |

| ONT MinION | Full-length 16S rRNA sequencing | Portable long-read sequencing [35] | |

| Illumina MiSeq | Short-read sequencing | Cost-effective, high-accuracy [36] | |

| Reference Databases | Greengenes | 16S rRNA reference database | Used by PICRUSt [31] |

| Genome Taxonomy Database | Taxonomic reference | Used by PICRUSt2 [29] | |

| KEGG | Functional pathway database | Source of functional annotations [31] | |

| Gene Ontology | Functional annotation system | Used by DeepFRI [32] | |

| Computational Tools | PICRUSt/PICRUSt2 | Functional prediction | Phylogenetic investigation of unobserved states [29] |

| Tax4Fun | Functional prediction | Reference-based prediction [29] | |

| DeepFRI | Deep learning annotation | 99% annotation coverage [32] | |

| REBEAN | Language model annotation | Reference and assembly-free [34] | |

| minitax | Taxonomic classification | Consistent across platforms [35] | |

| sourmash | Metagenome analysis | Excellent accuracy on SRS and LRS data [35] |

The selection of appropriate research reagents and computational resources significantly impacts the quality and reliability of functional prediction results [35]. DNA extraction methodology affects both yield and quality, with different kits demonstrating substantial variation in performance characteristics [35]. The Zymo Research Quick-DNA HMW MagBead Kit provides the most consistent results with minimal variation among replicates, though with moderate DNA yield [35]. The Macherey-Nagel kit offers the highest yield, while the Invitrogen kit provides moderate yields with higher variance [35]. The Qiagen kit consistently underperforms for microbial studies, producing the lowest yield and significant host DNA contamination in stool samples [35].

Sequencing technology selection introduces another critical decision point. Short-read sequencing (Illumina) remains the standard for cost-effective, high-accuracy applications, while long-read technologies (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) enable full-length 16S rRNA sequencing with higher taxonomic resolution [35] [30]. PacBio sequencing demonstrates superior species-level classification (74.14%) compared to short-read approaches (55.23%) [35]. Emerging computational tools like minitax provide consistent results across sequencing platforms, reducing methodology-induced variability in taxonomic classification [35].

Reference database selection introduces significant bias in functional prediction accuracy [29]. Tools relying on the Greengenes database (PICRUSt) or Genome Taxonomy Database (PICRUSt2) exhibit strong performance for human-associated microbiomes but degrade sharply for environmental samples [29]. This reflects the taxonomic bias in reference databases, which disproportionately represent human-associated microorganisms [29]. Next-generation approaches like DeepFRI and REBEAN aim to circumvent these limitations through deep learning and language models that reduce dependence on reference databases [32] [34].

Methodologies and Applications: Tools, Pipelines, and Real-World Implementation

This guide provides an objective comparison of PICRUSt2 and HUMAnN3, two fundamental tools for predicting the functional potential of microbial communities from sequencing data.

PICRUSt2 (Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States 2) and HUMAnN3 (The HMP Unified Metabolic Analysis Network 3) represent distinct methodological approaches for functional profiling.

PICRUSt2 predicts metagenome functions from 16S rRNA marker gene sequences [37]. It operates on the principle that evolutionary related microbes share similar functional traits. The tool uses a hidden state prediction algorithm to infer the gene content of environmentally sampled organisms based on their phylogenetic placement within a reference tree of genomes with known functional annotations [37].

HUMAnN3, in contrast, is a pipeline for directly quantifying metabolic pathway abundance and coverage from shotgun metagenomic sequencing data [11]. It maps sequencing reads to a comprehensive database of reference genomes and metabolic pathways, providing a direct measurement of the functional genes present in a microbial community [11].

The table below summarizes their core methodological differences:

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of PICRUSt2 and HUMAnN3

| Feature | PICRUSt2 | HUMAnN3 |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Input Data | 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequences [37] | Whole-genome shotgun metagenomic sequences [11] |

| Underlying Principle | Phylogenetic imputation [37] | Direct read mapping to reference databases [11] |

| Key Outputs | Predicted abundance of gene families (e.g., KEGG Orthologs) [37] | Abundance and coverage of metabolic pathways (e.g., MetaCyc) and gene families [11] |

| Typical Cost | Lower (amplicon sequencing) [38] | Higher (shotgun sequencing) [38] |

Experimental Performance and Benchmarking Data

Performance benchmarking reveals critical differences in accuracy and application scope between the two tools.

Prediction Accuracy and Concordance with Shotgun Data

PICRUSt2 was validated against shotgun metagenomic sequencing (MGS) across seven datasets, including human gut, primate stool, and environmental samples [37]. The similarity between PICRUSt2-predicted KEGG Ortholog (KO) abundances and those from MGS was measured using Spearman correlation, with results ranging from 0.79 to 0.88 across different environments [37]. However, a separate study cautions that strong correlation coefficients can be misleading, as they may be driven by gene families that co-occur across many genomes rather than accurate sample-specific predictions [39].

When evaluated on its ability to reproduce differential abundance results from MGS data, PICRUSt2 demonstrated an F1 score (the harmonic mean of precision and recall) ranging from 0.46 to 0.59 [37]. Its precision—the proportion of its significant findings that were confirmed by MGS—ranged from 0.38 to 0.58 [37].

Comparative Performance in Biological Discrimination

A direct comparison using real datasets evaluated how well each tool could group samples based on known biological categories (e.g., host phenotype). The following table summarizes the clustering purity achieved by each tool's functional profiles against taxonomic profiles [11]:

Table 2: Clustering Purity for Phenotype Discrimination Across Datasets (adapted from [11])

| Dataset | Phenotype | Bacterial Genera (Taxonomy) | PICRUSt2 (Predicted Pathways) | HUMAnN3 (Shotgun Pathways) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cameroonian Stool | Geography | 0.99 | 0.61 | 0.97 |

| Indian Stool | Geography | 0.98 | 0.69 | 0.98 |

| Mammalian Stool | Host Species | 0.99 | 0.68 | 0.99 |

| Blueberry Soil | Soil Type | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.64 |

This data shows that HUMAnN3's functional profiles consistently matched the high discriminatory power of taxonomic profiles in host-associated environments. PICRUSt2's predictions, while able to capture some phenotypic signal, showed lower concordance with the ground-truth phenotypes in these comparisons [11].

Scope and Limitations Across Environments

A critical limitation of prediction tools like PICRUSt2 is their dependence on reference databases, which are heavily biased toward human-associated microbes [39]. One study found that PICRUSt2 performed reasonably well for inference in human datasets but experienced a sharp decrease in performance for non-human and environmental samples (e.g., gorilla, mouse, chicken, and soil) [39]. Furthermore, performance varies by functional category, with better prediction accuracy for "housekeeping" functions like translation and replication, compared to more variable ecological functions [39].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducible results, the following outlines the standard workflows used in the cited benchmarking studies.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking PICRUSt2 Prediction Accuracy

This protocol describes the key validation steps for PICRUSt2, as performed in its foundational study [37].

- Input Preparation: Collect 16S rRNA marker gene sequences (e.g., Amplicon Sequence Variants - ASVs) from the samples of interest.

- Phylogenetic Placement: Place the ASVs into a reference phylogeny using HMMER and EPA-ng to determine their optimal position among 20,000 full-length 16S rRNA genes from bacterial and archaeal genomes [37].

- Hidden State Prediction: Use the

castorR package to predict the genomic content (gene family copy numbers) for each ASV based on its phylogenetic placement [37]. - Metagenome Prediction: Correct the ASV abundances by their predicted 16S rRNA copy number, then multiply by the inferred genomic content to produce a table of predicted gene family abundances (e.g., KEGG Orthologs) [37].

- Validation: Compare the predicted KO table to a gold-standard KO table obtained from shotgun metagenome sequencing of the same samples. Use Spearman correlation to assess rank-order similarity and differential abundance testing (e.g., Wilcoxon test) to compare inference results [37].

The workflow for this phylogenetic placement and prediction process is illustrated below.

Protocol 2: Comparative Analysis with HUMAnN3

This protocol outlines the steps for a direct comparison between PICRUSt2 and HUMAnN3, as performed in a later benchmarking study [11].

- Sample Preparation: Obtain samples with paired 16S rRNA amplicon and whole-genome shotgun (WGS) sequencing data from the same individuals or microcosms.

- PICRUSt2 Analysis:

- Process the 16S rRNA data through the PICRUSt2 pipeline to obtain predicted functional abundances (e.g., MetaCyc pathways) [11].

- HUMAnN3 Analysis:

- Process the WGS data with the HUMAnN3 pipeline.

- Perform quality control and trimming of reads using

fastp(v0.23.2) [11]. - For host-associated samples, filter out host-derived reads using

Bowtie2(v2.5.1) against the host reference genome [11]. - Run HUMAnN3 to obtain quantified abundances of microbial metabolic pathways.

- Data Transformation: For both tools, create sample-by-function abundance matrices.

- Statistical Evaluation:

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and k-means clustering on the functional abundance matrices.

- Set the value of k (number of clusters) based on the number of known phenotype categories in the dataset metadata (e.g., geographic location, host species).

- Calculate the Weighted Average Clustering Purity (WACP) to evaluate how well the functionally-derived clusters match the known biological categories [11].

The flow of this comparative analysis is summarized in the following diagram.

Research Reagent and Computational Solutions

The table below lists key software and database resources essential for implementing the aforementioned protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Item Name | Function/Purpose | Specifications / Version |

|---|---|---|

| PICRUSt2 Software | Predicts functional abundances from 16S rRNA data [37]. | Available at https://github.com/picrust/picrust2 |

| HUMAnN3 Software | Quantifies microbial metabolic pathways from WGS data [11]. | Version 3.0 as used in [11] |