Culture-Based vs Molecular Diagnostic Methods: A Comprehensive Comparison for Biomedical Research and Clinical Application

This article provides a critical analysis for researchers and drug development professionals comparing traditional culture-based methods with advanced molecular diagnostics.

Culture-Based vs Molecular Diagnostic Methods: A Comprehensive Comparison for Biomedical Research and Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a critical analysis for researchers and drug development professionals comparing traditional culture-based methods with advanced molecular diagnostics. It explores the foundational principles, methodological applications, operational challenges, and validation data for both approaches across diverse clinical scenarios including necrotizing soft tissue infections, chronic wounds, antimicrobial resistance surveillance, and urinary tract infections. The content synthesizes current evidence on sensitivity, specificity, turnaround time, and clinical utility, offering practical insights for method selection, troubleshooting, and future directions in diagnostic strategy.

Fundamental Principles: From Traditional Gold Standards to Molecular Revolution

For over a century, culture-based methods have served as the fundamental cornerstone of microbiological diagnosis, providing the definitive standard for detecting and identifying pathogens in clinical and research settings. This preeminence stems from their ability to isolate viable microorganisms, enabling comprehensive phenotypic characterization, antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST), and detailed strain typing. The historical reliance on culture is deeply embedded in Koch's postulates and traditional microbiological principles, which prioritize the isolation and propagation of pathogens as proof of infectious etiology.

However, the landscape of diagnostic microbiology is undergoing a profound transformation. The inherent limitations of culture methods—particularly their extended time-to-result and variable sensitivity—have become increasingly significant in an era demanding rapid, precise interventions. This has catalyzed the development and adoption of molecular diagnostics that offer revolutionary speed and sensitivity. This article objectively examines the historical context of culture as the gold standard, its documented limitations through comparative experimental data, and the emerging diagnostic paradigms reshaping pathogen detection in modern research and drug development.

The Traditional Gold Standard: Culture-Based Methods

Fundamental Principles and Workflow

Culture-based detection relies on the fundamental principle of propagating microorganisms on or in artificial nutrient media. The standard workflow involves inoculating a clinical specimen onto selective and/or non-selective media, followed by incubation for 24-48 hours or longer to allow for the growth of viable organisms. Subsequently, colony identification is performed using morphological assessment, biochemical tests, or mass spectrometry techniques like MALDI-TOF. For antimicrobial susceptibility testing, isolated colonies are subjected to disk diffusion, gradient diffusion, or automated broth microdilution systems, requiring additional 18-24 hours of incubation [1] [2].

The critical strength of this paradigm lies in its ability to provide a living isolate. This isolate can be used for comprehensive downstream analyses, including full AST profiles, whole-genome sequencing, and studies of pathogenicity. Furthermore, culture methods are widely accessible and do not require the sophisticated instrumentation or specialized technical expertise needed for molecular assays, making them a universal first-line tool across diverse laboratory settings.

Documented Limitations in Modern Context

Despite its historical status, extensive research has quantified significant constraints of culture-based methods:

- Prolonged Time-to-Result (TTR): The multi-step process inherently creates delays. Studies consistently report a TTR of 48 to 72 hours for a complete identification and AST profile [1] [2]. This delay can critically impact patient management in sepsis and other acute infections and slow down research workflows in drug development.

- Limited Sensitivity: Culture sensitivity is dependent on the viability and cultivability of pathogens under artificial laboratory conditions. Fastidious organisms, those inhibited by prior antibiotic exposure, or those present in low microbial bioburden samples may fail to grow, leading to false-negative results. A year-long comparative study on carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacilli (CPGNB) reported a sensitivity of just 46.3% for a culture-based strategy when non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli were disregarded, rising only to 64.8% when they were included [3].

- Labor-Intensive Processes: Culture methods require substantial hands-on technical time for media preparation, specimen plating, subculturing, and manual interpretation, making them less amenable to high-throughput screening in large-scale studies [3].

The Molecular Paradigm: A Comparative Analysis

Molecular diagnostics represent a paradigm shift from cultivating organisms to directly detecting their genetic material. These techniques bypass the need for growth, offering a direct pathway from specimen to result.

- Multiplex PCR (mPCR): Systems like the Allplex Entero-DR assay and the Xpert Carba-R assay can simultaneously identify a panel of resistance genes (e.g., blaKPC, blaNDM, blaVIM, blaIMP, blaOXA-48, blaCTX-M, vanA, vanB) directly from rectal swabs and other specimens within a few hours [2].

- Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR): This technique offers absolute quantification of nucleic acids, showing high sensitivity for diagnosing bloodstream infections, even with low pathogen loads [4] [5].

- Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS): mNGS provides a hypothesis-free approach, capable of identifying all nucleic acids in a sample—bacterial, viral, and fungal—without prior knowledge of the pathogen, making it powerful for detecting novel or unexpected organisms [4] [5].

Head-to-Head Performance Data

Recent large-scale studies provide robust quantitative comparisons between culture and molecular methods, particularly for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) surveillance.

Table 1: Comparative Diagnostic Performance for CPGNB/CPE Detection

| Metric | Xpert Carba-R (Molecular) | Culture-Based Method | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 90.2% [3] / 97.2% [1] | 46.3% - 64.8% [3] | 29,446 samples; moderate-prevalence setting [3] |

| Specificity | >99% [1] | Not directly comparable (Reference) | 4,120 high-risk patients [1] |

| Avg. Hands-on Time | 1.3 minutes [3] | 89.97 minutes [3] | Hands-on time per sample [3] |

| Total Turnaround Time (TAT) | ~1.26 hours [1] | ~55.35 hours [1] | From sample to final result [1] |

| Key Advantage | Speed, sensitivity, automation | Specificity, provides viable isolate | - |

Table 2: Performance of a Multiplex PCR Assay (Allplex Entero-DR) [2]

| Parameter | Result |

|---|---|

| Samples Analyzed | 300 rectal swabs |

| Positive by Multiplex PCR | 188 (62.6%) |

| Sensitivity | 100% |

| Negative Predictive Value (NPV) | 100% |

| Targets Detected | blaKPC, blaOXA-48, blaVIM, blaNDM, blaIMP, blaCTX-M, vanA, vanB |

The data demonstrates the consistent superiority of molecular methods in speed and sensitivity. The near 100% Negative Predictive Value (NPV) is particularly noteworthy; it means a negative molecular test can reliably exclude colonization or infection with a high degree of confidence, allowing researchers and clinicians to rule out targets efficiently [2].

Experimental Protocols: A Closer Look

Detailed Protocol: Culture-Based CPGNB Detection

The following methodology is representative of the protocols used in the cited comparative studies [3] [1]:

- Specimen Collection & Inoculation: Rectal swabs are collected in transport media (e.g., Copan Faecal Swab with Cary-Blair medium). An aliquot (e.g., 10 μL) of the transport medium is inoculated onto selective chromogenic agar plates, such as ChromID CARBA SMART or similar.

- Incubation: The inoculated agar plates are incubated at 35–37°C under aerobic conditions for 24-48 hours.

- Colony Identification: Colonies with morphology suggestive of target organisms (e.g., metallic blue on ChromID CARBA SMART for E. coli) are selected for further analysis. Identification is confirmed using techniques like MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

- Confirmation of Carbapenemase Production:

- Phenotypic Testing: A modified Hodge test or similar phenotypic assay may be performed.

- Molecular Confirmation: Isolated colonies are typically subjected to a confirmatory PCR-based test (e.g., Xpert Carba-R) to identify the specific carbapenemase gene present.

Detailed Protocol: Direct Molecular Detection (Xpert Carba-R Assay)

The protocol for direct-from-specimen testing is significantly streamlined [3] [1]:

- Sample Preparation: The rectal swab is suspended in a specific Sample Reagent (containing sodium citrate and cysteine). The mixture is vortexed for 10 seconds to homogenize the sample and lyse the bacteria.

- Loading & Automation: A precise volume (e.g., 1.7 mL) of the homogenized mixture is transferred into the single-use Xpert Carba-R cartridge using a provided pipette.

- Integrated Analysis: The cartridge is loaded into the GeneXpert platform, which automates all subsequent steps: nucleic acid extraction, purification, amplification via real-time PCR, and target detection.

- Result Reporting: The system software automatically analyzes the fluorescence data and reports the presence or absence of the targeted carbapenemase genes (blaKPC, blaNDM, blaVIM, blaIMP-1, blaOXA-48). The entire process from cartridge loading to result is typically completed in under 90 minutes with minimal hands-on time.

Workflow Visualization

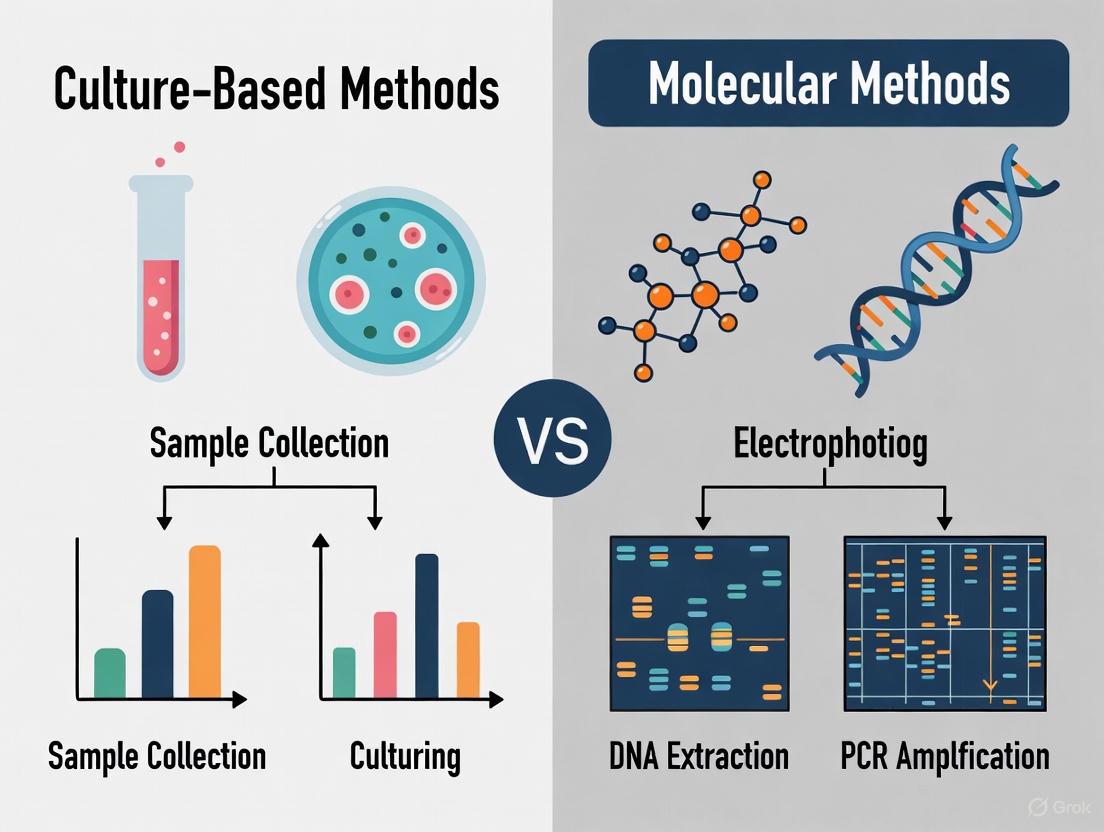

The following diagram illustrates the stark contrast in complexity and time investment between the two methodologies, highlighting the key bottleneck of incubation in the culture-based workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The experiments cited rely on specific, commercially available reagents and platforms to ensure reproducibility and accuracy.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for AMR Detection Studies

| Item Name | Function / Target | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| ChromID CARBA SMART Agar (bioMérieux) | Selective chromogenic culture medium | Differentiates carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales based on colony color; used as a culture-based comparator [3]. |

| Xpert Carba-R Assay (Cepheid) | Multiplex real-time PCR | Detects & differentiates five major carbapenemase gene families (blaKPC, blaNDM, blaVIM, blaIMP-1, blaOXA-48) directly from specimens or isolates [3] [1]. |

| GeneXpert Platform (Cepheid) | Automated molecular diagnostic system | Integrates sample preparation, amplification, and detection in a single, self-contained cartridge; enables rapid, hands-off molecular testing [1]. |

| Allplex Entero-DR Assay (Seegene) | Multiplex real-time PCR | Simultaneously detects a broad panel of β-lactamase (blaCTX-M, carbapenemases) and vancomycin resistance (vanA/B) genes from surveillance samples [2]. |

| Copan Faecal Swab (COPAN) | Specimen collection & transport | Contains liquid Cary-Blair medium to preserve the viability of microorganisms during transport for both culture and molecular testing [1] [2]. |

| 1,2-O-Dilinoleoyl-3-O-Beta-D-Galactopyranosylracglycerol | 1,2-O-Dilinoleoyl-3-O-Beta-D-Galactopyranosylracglycerol, MF:C45H78O10, MW:779.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (S)-2-(3-Bromophenyl)propanoic acid | (S)-2-(3-Bromophenyl)propanoic acid, MF:C9H9BrO2, MW:229.07 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Challenges and Nuances in Molecular Diagnostics

Despite their superior analytical performance, molecular methods are not without limitations, which are crucial for researchers to consider when interpreting data.

- Discordance in Genotype Detection: A significant challenge is the occasional discordance between direct molecular testing and culture-based results. For instance, one study noted that the positive predictive value (PPV) for the blaIMP-1 gene using the Xpert Carba-R assay was 0%, as none of the nine positive detections from stool were confirmed in corresponding cultured isolates [1]. This highlights that molecular tests can detect genes from non-viable organisms or those present below the threshold for culture growth, which may not always represent a active, transmissible colonization.

- The Clinical Accuracy Gap: Perhaps the most critical nuance is that the dramatic improvement in analytical sensitivity and speed has not always translated into unequivocal improvements in patient outcomes in clinical trials. As noted by Li et al., "While molecular diagnostics excel in sensitivity, their real-world impact on specificity and patient prognosis - clinical accuracy - remains limited" [4] [5]. This gap can stem from challenges in interpreting multi-positive results, distinguishing colonization from infection, and the complex interplay of host factors in determining clinical outcomes [5].

- Inability to Provide a Live Isolate: Molecular methods detect genetic targets but do not yield a viable isolate for further study. This is a critical limitation for research requiring downstream phenotypic analyses, such as comprehensive antimicrobial susceptibility testing, whole-genome sequencing, or investigating pathogenicity mechanisms.

The evidence demonstrates that while culture-based methods retain an essential role in microbiology by providing a viable isolate for comprehensive phenotypic characterization, their status as an unassailable "gold standard" is no longer tenable in many diagnostic and research contexts. Their principal limitations—prolonged turnaround times and suboptimal sensitivity—are quantitatively addressed by modern molecular techniques.

Molecular diagnostics have established a new benchmark for speed and analytical sensitivity, as rigorously documented in head-to-head comparisons for AMR surveillance. However, the transition to a molecular-centric paradigm is nuanced. Researchers must critically navigate challenges such as result interpretation, genotype-phenotype correlation, and the current lack of a live isolate for further investigation. The future of microbiological diagnosis lies not in the supremacy of one method over the other, but in their strategic integration. Leveraging the unparalleled speed of molecular tools for initial screening and rapid guidance, followed by the phenotypic precision of culture for confirmation and isolate retrieval, represents the most powerful and rational path forward for both clinical science and drug development.

Clinical microbiology is defined by the ongoing pursuit of a critical balance: the need for rapid, actionable results versus the requirement for accurate, comprehensive pathogen characterization. For decades, this balance has been maintained by culture-based methods that represent the historical cornerstone of pathogen identification. These methods, which include isolation on selective media, phenotypic profiling, and antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST), provide the foundational framework for clinical bacteriology [6] [7]. However, the landscape of infectious disease diagnostics is undergoing a profound transformation. The emergence and global spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), now considered a major global health burden, has intensified the need for faster diagnostic solutions [8]. This urgency is compounded by data showing that delayed administration of effective antimicrobials is directly associated with increased mortality in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock [8] [6].

In response to these pressures, molecular diagnostic techniques have rapidly evolved as powerful alternatives or complementary tools. These methods, particularly nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), offer the potential to drastically reduce the time to results, in some cases providing actionable data within hours rather than days [9] [10]. This guide provides a systematic, evidence-based comparison of these two diagnostic paradigms—culture-based versus molecular methods—framed within the broader thesis that the future of clinical microbiology lies not in the supremacy of one approach over the other, but in their strategic integration. We will objectively compare their performance using published experimental data, detail key methodologies, and visualize their workflows to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a clear understanding of the current diagnostic landscape.

Core Principles and Methodologies: A Detailed Comparison

Conventional Culture-Based Methods: The Established Gold Standard

Conventional culture methods form the multi-step backbone of traditional clinical microbiology. The process begins with sample inoculation onto solid or liquid culture media. For bloodstream infections, this typically involves incubating blood samples in culture bottles, which can take up to 5 days for bacterial growth detection, though it often occurs within the first 24 hours [6]. Following detection of microbial growth, the next step is bacterial isolation to obtain pure colonies, which typically requires an additional 24 hours [6]. The isolated colonies then undergo phenotypic identification based on morphological characteristics, Gram staining, and biochemical profiling.

The final and often most critical step is phenotypic Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST), which evaluates bacterial response to antimicrobial agents in vitro to guide therapeutic decisions [8]. The gold standard phenotypic AST methods include:

- Broth and Agar Dilution: A standard bacterial inoculum is added to agar or broth containing two-fold serial dilutions of an antimicrobial agent. After overnight incubation, the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) is determined as the lowest concentration that inhibits visible bacterial growth [8] [11].

- Kirby-Bauer Disk Diffusion: A standard inoculum is spread on a Mueller-Hinton Agar plate, and antibiotic-impregnated disks are placed on the surface. After 18-24 hours of incubation, the diameter of the zone of inhibition around each disk is measured and interpreted using established clinical breakpoints [8].

- Gradient Diffusion Methods (E-test): A predefined antibiotic gradient is applied to a strip placed on an inoculated agar plate. After incubation, the MIC is read at the intersection of the elliptical zone of inhibition with the strip [8].

The primary limitation of these conventional methods is their prolonged turnaround time, requiring at least 72 hours from specimen collection to final susceptibility results, which can critically delay targeted antimicrobial therapy [6].

Molecular Methods: The Rise of Rapid Diagnostics

Molecular techniques for pathogen detection have emerged to address the speed limitations of culture-based methods. These approaches primarily rely on detecting pathogen-specific nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) and can be broadly categorized into two types: single-pathogen tests and multiplexed panels.

A pivotal step in any molecular workflow is the efficient extraction of bacterial DNA, which significantly impacts downstream detection sensitivity. Multiple DNA extraction methodologies have been developed and compared in the literature:

- Column-Based Extraction: Kits such as the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen) use silica-based columns to bind and purify DNA after lysis. While widely used, one study found this method had an accuracy of 65.0% for E. coli detection from whole blood, underperforming compared to newer methods [12].

- Magnetic Bead-Based Extraction: Methods like the K-SL DNA Extraction Kit and the automated GraBon system use magnetic beads to isolate bacteria from whole blood before lysis, providing a cleaner sample. These demonstrated superior accuracy rates of 77.5% and 76.5% respectively for E. coli detection [12].

- Enzymatic and Non-Enzymatic Enrichment Methods: The MolYsis system enzymatically removes human DNA to enrich for pathogen DNA but is noted to be labor-intensive [13]. The novel Polaris method provides a non-enzymatic, more rapid pathogen DNA enrichment, enabling reliable detection from 5 ml of blood with a 70-75% detection rate at clinically relevant concentrations of 1 CFU/ml [13].

- In-House Extraction Protocols: Some studies have developed modified in-house methods, such as a chloroform-isoamyl alcohol protocol, which showed statistically similar sensitivity to commercial kits while maintaining high rapidity and much lower cost [9].

Following DNA extraction, the primary molecular detection techniques include:

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Electrophoresis: Conventional and real-time PCR amplify target DNA sequences, with products detected via gel electrophoresis or fluorescent probes in real-time. One study protocol involved initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation, annealing (at 52-58°C), and elongation, with final analysis by agarose gel electrophoresis [9].

- Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP): This technique operates at a constant temperature (65°C) for 30-60 minutes, using multiple primers for high specificity and sensitivity. It is considered simpler and more rapid than PCR as it doesn't require thermal cycling equipment [9]. One evaluation found LAMP more promising than PCR-electrophoresis due to its simplicity, high rapidity, and sensitivity [9].

- Microarray-Based Systems: Platforms like the Clart Pneumovir Kit use hybridization patterns on a microarray chip to detect multiple pathogens simultaneously, with analysis performed using optical equipment [10].

- Automated, Integrated Systems: Newer systems combine extraction, amplification, and detection. For instance, the hypothetical MyCrobe system (envisioned for 2025) integrates nucleic acid and antigen detection from clinical specimens to provide results in approximately 15 minutes [7].

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Analysis

Speed, Sensitivity, and Accuracy

The following tables synthesize quantitative performance data from published comparative studies to provide an objective assessment of method capabilities.

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Extraction Method Performance from Whole Blood

| Extraction Method | Technology Type | Pathogen Detected | Accuracy/Detection Rate | Sample Volume | Time Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit [12] | Column-based | E. coli | 65.0% | 200 µL | Standard |

| S. aureus | 67.5% | 200 µL | Standard | ||

| K-SL DNA Extraction Kit [12] | Magnetic bead-based | E. coli | 77.5% | 200 µL | Standard |

| S. aureus | 67.5% | 200 µL | Standard | ||

| GraBon System [12] | Automated magnetic bead | E. coli | 76.5% | 500 µL | Standard |

| S. aureus | 77.5% | 500 µL | Standard | ||

| Polaris Method [13] | Non-enzymatic enrichment | S. aureus (10 CFU/mL) | 100% | 5 mL | ~45 minutes |

| S. aureus (1 CFU/mL) | 70-75% | 5 mL | ~45 minutes | ||

| MolYsis Method [13] | Enzymatic enrichment | S. aureus (10 CFU/mL) | 50-67% | 5 mL | ~2 hours |

| S. aureus (1 CFU/mL) | 17-50% | 5 mL | ~2 hours | ||

| In-House (Phenol-Chloroform) [9] | Chemical purification | Foodborne Pathogens | Similar to commercial kits | 1 mL | Lower cost, high rapidity |

Table 2: Performance of Rapid Phenotypic AST Platforms for Bloodstream Infections

| Platform (Manufacturer) | Technology Principle | Acceptable Specimens | Time to Result (after positive culture) | Categorical Agreement (CA) | Essential Agreement (EA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VITEK REVEAL (bioMérieux) [14] [8] | Colorimetric sensors detecting volatile organic compounds from bacterial metabolism | Positive Blood Cultures | ~5 hours | 98.3% | 97.1% |

| PhenoTest BC (Accelerate Diagnostics) [8] | Morphokinetic cellular analysis, fluorescence in situ hybridization | Positive Blood Cultures | ID: 2 h, AST: 7 h | 92-99% | 82-97% |

| QuickMIC (Gradientech) [8] | Microscopic analysis of microfluidic device | Positive Blood Cultures | 2-4 hours | 78-100% | 45-100% |

| FASTinov [8] | Flow cytometry with fluorescent dyes (growth-independent) | Positive Blood Cultures | ~2 hours | >96% | N/R |

| dRAST (QuantaMatrix) [8] | Time-lapse microscopic imaging | Positive Blood Cultures | 4-7 hours | 91-92% | >95% |

Table 3: Molecular vs. Conventional Method Detection for Respiratory Viruses [10]

| Virus | Immunofluorescence/ Viral Culture (IF/VC) | Seeplex RV12 | Clart Pneumovir |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSV | 11 | 7 | 12 |

| Adenovirus | 13 | 14 | 13 |

| Rhinovirus | 2 | 17 | 27 |

| Human Bocavirus (HBoV) | N/D | N/D | 16 |

| Total Positives (n=80 samples) | 37 | 40 | 62 |

Critical Analysis of Comparative Performance

The data reveal distinct, complementary strengths and limitations for each methodological approach. Culture-based methods maintain their position as the comprehensive gold standard, providing viable isolates for further characterization and full phenotypic AST profiles. However, their most significant drawback remains the extended turnaround time of 48-72 hours or more to final results [6]. Furthermore, conventional methods require specialized infrastructure, are labor-intensive, and have a complex supply chain that can limit implementation in low-resource settings [6].

Molecular methods demonstrate clear advantages in speed, with some rapid AST platforms delivering results in 2-7 hours after a positive blood culture [8] [14]. Sensitivity is also a key strength, with technologies like the Polaris system enabling detection at clinically relevant concentrations as low as 1 CFU/mL blood [13]. However, molecular methods face their own challenges. They generally require expensive equipment and trained personnel [9] [11]. The detection of nucleic acids does not necessarily indicate viable, clinically relevant infection, potentially leading to false positives from non-viable organisms or environmental contamination [10]. Perhaps most critically for AMR management, most genotypic methods detect only a limited number of pre-defined resistance targets and may miss novel or uncommon resistance mechanisms [6]. One review noted that a carbapenemase gene is identifiable in fewer than 50% of bacteria found to be phenotypically carbapenem resistant [6].

Visualizing Diagnostic Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the procedural flow and time investment for both conventional and modern diagnostic pathways, highlighting critical decision points and opportunities for integration.

Diagram 1: Comparative diagnostic workflows showing the significant time difference between conventional culture-based methods (72+ hours) and molecular methods (3-8 hours).

Diagram 2: Classification of rapid phenotypic AST platforms by their underlying detection technologies, showcasing the diversity of innovation in this field.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Key Reagents, Kits, and Platforms for Diagnostic Method Comparison

| Product/Platform Name | Type/Category | Primary Function | Key Features / Experimental Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen) [12] | DNA Extraction Kit | Column-based nucleic acid purification | Benchmark for comparison studies; processes 200 µL blood samples directly. |

| NucleoSpin Food (Macherey-Nagel) [9] | DNA Extraction Kit | DNA purification from complex food matrices | Used in comparative studies for pathogen detection from food samples. |

| K-SL DNA Extraction Kit (KingoBio) [12] | DNA Extraction Kit | Magnetic bead-based bacterial DNA extraction | Incorporates bacterial isolation from whole blood before lysis; enhances purity. |

| GraBon (KingoBio) [12] | Automated Platform | Automated DNA extraction system | Uses same reagents as K-SL kit with robotic handling; processes 500 µL sample. |

| MolYsis Complete5 Kit (Molzym) [13] | DNA Extraction Kit | Enzymatic pathogen DNA enrichment | Selectively removes human DNA from up to 5 mL blood; improves sensitivity. |

| Polaris System (Biocartis) [13] | Pathogen DNA Enrichment | Non-enzymatic pathogen DNA isolation | Fast (45 min), sensitive detection from 5 mL blood; compared to MolYsis. |

| VITEK REVEAL (bioMérieux) [14] [8] | Rapid AST System | Phenotypic susceptibility testing | Colorimetric sensors detect metabolic VOCs; ~5h TTR from positive blood culture. |

| PhenoTest BC (Accelerate Diagnostics) [8] | Rapid ID & AST System | Combined identification & AST | Uses morphokinetic analysis and FISH; AST in 7h from positive culture. |

| WarmStart Colorimetric LAMP Master Mix [9] | Amplification Reagent | Isothermal nucleic acid amplification | Enables visual detection of amplification; used in rapid, equipment-free protocols. |

| OneTaq Hot Start Master Mix (NEB) [9] | Amplification Reagent | PCR amplification | Standard master mix for conventional PCR-based detection protocols. |

| MyCrobe System (Hypothetical) [7] | Integrated Molecular System | Hand-held molecular diagnostics | Conceptual future device combining nucleic acid and antigen detection in minutes. |

| Pyrocatechol monoglucoside | Pyrocatechol monoglucoside, MF:C12H16O7, MW:272.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2',4'-Dihydroxy-3,7':4,8'-diepoxylign-7-ene | 2',4'-Dihydroxy-3,7':4,8'-diepoxylign-7-ene, MF:C18H18O4, MW:298.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The diagnostic landscape is rapidly evolving, influenced by several powerful trends. Automation and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are poised to dominate the future of clinical laboratories. AI is expected to reduce time-consuming repetitive tasks, suggest reflex testing based on initial results, and enhance the accuracy and throughput of laboratory operations [15]. Digital pathology and AI-powered algorithms are also being developed to increase efficiencies and help alleviate workforce shortages [15]. Furthermore, automation systems, widely adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic, are now being deployed to handle manual aliquoting and pre-analytical steps, improving quality, reliability, and turnaround time [15].

The paradigm is shifting from a competitive to a complementary diagnostic framework. The future of clinical microbiology lies in the strategic integration of both culture-based and molecular methods, leveraging the strengths of each. Culture methods remain essential for comprehensive phenotypic AST, outbreak investigation, and epidemiological surveillance, as they provide the live isolates necessary for these purposes [6]. Molecular methods, with their unprecedented speed, are critical for early, sensitive pathogen detection, guiding initial empiric therapy, and detecting pathogens that are slow-growing or difficult to culture [9] [10].

In conclusion, while molecular techniques offer revolutionary speed and sensitivity, phenotypic culture-based methods continue to provide the indispensable reference standard for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. The most effective diagnostic pipelines will therefore utilize an integrated approach: employing rapid molecular assays for early detection and initial guidance, while relying on cultured isolates for definitive phenotypic confirmation and further characterization. This synergistic model, enhanced by automation and AI, represents the most promising path forward for improving patient outcomes and combating the global threat of antimicrobial resistance.

The shift from traditional culture-based methods to molecular techniques represents a paradigm shift in microbiological research and clinical diagnostics. Culture-based methods, long considered the gold standard, are often limited by prolonged turnaround times, low sensitivity for fastidious organisms, and the inability to detect non-culturable pathogens. Molecular methods, founded on nucleic acid extraction, amplification, and sequencing, have overcome these limitations, offering unprecedented speed, sensitivity, and specificity. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these foundational technologies, equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the data needed to select optimal methodologies for their specific applications.

Nucleic Acid Extraction Technologies

The efficacy of any molecular assay is fundamentally dependent on the quality and quantity of the extracted nucleic acid. The choice of extraction method significantly influences downstream results, making selection a critical first step.

Comparison of Extraction Method Performance

The following table summarizes the performance of various nucleic acid extraction methods based on recent comparative studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Nucleic Acid Extraction Methods

| Extraction Method | Sample Type | Key Performance Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Bead-Based | Cervical Swabs (HPV) | Detection rate of 20.66%; superior anti-interference; cost increased by 13.14% but detection rate increased by 106.19%. | [16] |

| Boiling Method | Cervical Swabs (HPV) | Detection rate of 10.02%; failed when hemoglobin > 30 g/L. | [16] |

| Combination Approach | Processed Chestnut Rose Juice | Highest DNA quality and PCR amplification efficiency; more time-consuming and costly. | [17] |

| Modified CTAB-Based | Processed Chestnut Rose Juice | High DNA concentration; poor DNA quality and PCR performance. | [17] |

| Automated Systems (KingFisher, Maxwell, GenePure) | Human Stool Samples | Demonstrated differences in DNA yield, purity, and subsequent 16S rRNA sequencing profiles; bead-beating crucial for microbial lysis. | [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, below are the detailed protocols for two key compared methods.

Protocol 1: Magnetic Bead-Based DNA Extraction for HPV Detection [16] This protocol uses the qEx-DNA/RNA virus T183 kit (Tianlong Corporation) on a PANA 9600s instrument.

- Lysis: A 300 µL sample is transferred to a plate and mixed with lysis buffer to break open cells and viruses.

- Binding: Magnetic beads are added, which bind the liberated nucleic acids.

- Washing: The bead-nucleic acid complex is subjected to multiple wash steps to remove contaminants like proteins and salts. The process is automated, with magnetic attraction used to separate beads from supernatants.

- Elution: Purified DNA is eluted from the magnetic beads in a low-salt elution buffer. The final 5 µL eluate is used for subsequent PCR reactions.

Protocol 2: DNA Extraction from Processed Food Matrices [17] This "combination approach" for challenging samples like Chestnut rose juice involves:

- Lysis: Cell lysis using a combination of chemical and mechanical methods to break down tough plant and processed food matrices.

- Purification: A multi-step purification process, often involving silica-based columns or specialized solutions, to remove PCR inhibitors common in food (e.g., polyphenols, polysaccharides).

- Assessment: The quantity and quality of the extracted DNA are assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and gel electrophoresis. The DNA's amplifiability is confirmed with real-time PCR using species-specific primers (e.g., for the Internal Transcribed Spacer 2 (ITS2) region).

Extraction Workflow and Selection

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting an appropriate nucleic acid extraction method based on sample type and downstream application.

Nucleic Acid Amplification Techniques

Following extraction, nucleic acid amplification is employed to detect and quantify specific genetic targets. While Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is the most ubiquitous, several isothermal techniques offer compelling alternatives.

Comparison of Amplification Techniques

The table below provides a side-by-side comparison of the key characteristics of major amplification technologies.

Table 2: Characteristics of Major Nucleic Acid Amplification Techniques (NAATs) [19]

| Technique | Principle | Template | Temperature | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | Thermal cycling, enzyme: DNA polymerase | DNA | Thermo-cycling | High sensitivity, gold standard, versatile | Requires thermal cycler |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcription + PCR | RNA | Thermo-cycling | High sensitivity for RNA, quantitative | Requires thermal cycler |

| LAMP | Auto-cycling strand displacement, enzyme: Bst polymerase | DNA | Isothermal (~65°C) | Rapid, simple, visual detection, equipment-free | Complex primer design |

| NASBA | Enzymatic RNA amplification, enzymes: Reverse transcriptase, RNase H, T7 RNA polymerase | RNA | Isothermal (~41°C) | High sensitivity for RNA, rapid | Expensive kits, complex master mix |

| TMA | Similar to NASBA | RNA / DNA | Isothermal | Highly sensitive, rapid (<2 hours) | - |

| SDA | Enzymatic nicking and displacement | DNA | Isothermal | High sensitivity, can amplify ss/dsDNA | Shorter product size (<1kb) |

Key Research Reagent Solutions

A successful molecular amplification assay relies on a suite of specialized reagents.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Nucleic Acid Amplification and Analysis

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Tellgenplex HPV27 DNA Test | Multiplex PCR and hybridization for 27 HPV genotypes. | Genotyping of human papillomavirus from cervical swabs. [16] |

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard | Defined mock microbial community. | Positive control and standardization for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing studies. [18] |

| Nextera DNA Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries from fragmented DNA. | Library construction for Illumina NGS platforms. [18] |

| DNA Binding Magnetic Beads | Solid-phase reversible immobilization for nucleic acid purification. | Automated extraction of DNA/RNA from various biological samples. [16] [18] |

| Real-time PCR Master Mix | Optimized buffer, enzymes, dNTPs, and fluorescent dye/probe chemistry. | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) for gene expression or pathogen detection. [17] |

Nucleic Acid Sequencing Technologies

Sequencing technologies have evolved from reading single genes to deciphering entire genomes, enabling comprehensive analysis of genetic information.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Platforms

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), or Massively Parallel Sequencing (MPS), is the cornerstone of modern genomics, allowing for the simultaneous sequencing of millions of DNA fragments [20] [21].

Table 4: Comparison of Key DNA Sequencing Platforms and Technologies [20] [22] [21]

| Sequencing Technology / Platform | Read Length | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina (NovaSeq X, MiSeq) | Short-read (200-300 bp) | High accuracy, ultra-high throughput, low cost per genome. | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), targeted sequencing, metagenomics, transcriptomics. |

| Ion Torrent (GeneStudio S5) | Short-read (up to 600 bp) | Semiconductor-based detection, rapid run times, scalable chip formats. | Targeted sequencing, cancer research, infectious disease. |

| Oxford Nanopore (MinION, PromethION) | Long-read (ultra-long >100 kb) | Real-time sequencing, portable, direct RNA sequencing, high throughput. | Genome assembly, structural variant detection, real-time surveillance, epigenetics. |

| PacBio (HiFi Reads) | Long-read ( >15 kb) | High accuracy (>99.9%), circular consensus sequencing. | De novo genome assembly, haplotype phasing, variant discovery. |

| Roche SBX (Sequencing by Expansion) | N/A (Novel chemistry) | Novel Xpandomer chemistry, CMOS-based detection, high throughput. (Launch 2026) | High-throughput genome sequencing. [21] |

| Element AVITI | Short-read (300 bp) | Q40-level accuracy, flexible and cost-effective benchtop system. | Broad research applications. [21] |

The Integrated Molecular Diagnostics Workflow

The synergy between extraction, amplification, and sequencing is best demonstrated in advanced diagnostic applications. The following diagram outlines a modern workflow for pathogen detection, such as in culture-negative infective endocarditis, integrating molecular methods with traditional approaches.

The molecular toolkit, comprising nucleic acid extraction, amplification, and sequencing technologies, has fundamentally transformed biological research and clinical diagnostics. As this guide illustrates, the selection of methods is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor. The optimal choice hinges on the sample matrix, the required sensitivity and specificity, the scale of the project, and the available resources. While culture-based methods retain value for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, the future lies in integrated, multimodal approaches. The continued evolution of these technologies—particularly the rise of third-generation sequencing, point-of-care molecular platforms, and the integration of AI for data analysis—promises to further enhance our ability to decipher complex biological systems, accelerate drug discovery, and usher in a new era of precision medicine.

Biofilms are structured communities of microbial cells enclosed in a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that adhere to biological or inert surfaces [23] [24]. This matrix, composed of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and extracellular DNA (eDNA), creates a protective environment that allows microbes to persist in extreme conditions and resist antimicrobial agents and host immune responses [25] [26]. It is estimated that up to 80% of bacterial and archaeal cells exist in biofilm form in nature, representing the predominant mode of microbial life [25] [26].

The diagnostic challenge emerges from this very structure. The EPS matrix acts as a physical and chemical barrier, while the heterogeneous nature of biofilms—containing metabolically dormant cells alongside active ones—creates populations with differential susceptibility to treatments [24] [27]. Traditional culture-based methods, developed for free-floating (planktonic) bacteria, frequently fail to accurately identify the complex microbial consortia within biofilms, leading to inadequate treatments and persistent infections [28] [29]. This review systematically compares traditional culture-based and modern molecular diagnostic methods for biofilm-associated infections, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for method selection.

How Biofilms Confer Resistance and Evade Detection

The Protective Architecture of Biofilms

The resilience of biofilms stems from their complex structure and composition. The EPS matrix provides mechanical stability and limits the penetration of antimicrobial agents [24] [27]. Beyond this physical barrier, biofilms exhibit heterogeneous metabolic activity, with gradients of nutrients and oxygen creating varied microenvironments from the surface to the core [24] [26]. This spatial organization supports the survival of dormant persister cells that exhibit exceptional tolerance to antibiotics [27].

Table 1: Key Components of the Biofilm Extracellular Matrix and Their Protective Functions

| Matrix Component | Primary Functions | Impact on Resistance & Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Exopolysaccharides | Structural integrity, adhesion, barrier formation | Limits antibiotic penetration; traps antimicrobial agents |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | Structural support, genetic information exchange | Facilitates horizontal gene transfer of resistance genes |

| Proteins & Enzymes | Metabolic cooperation, matrix stabilization | Degrades some antimicrobial compounds; enhances stability |

| Water (up to 97%) | Hydration, nutrient diffusion | Creates dissolution gradients for antimicrobial agents |

Genetic Regulation and Communication

Biofilm development is precisely regulated through quorum sensing (QS), a cell-density dependent communication system that coordinates gene expression across the microbial community [24] [27]. In Gram-negative bacteria, LuxI/LuxR-type systems using acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) regulate biofilm maturation and virulence factor production, while Gram-positive bacteria employ oligopeptide-based two-component systems [27]. This coordinated behavior enables biofilms to mount unified defensive responses to environmental threats, including antibiotic challenges.

The following diagram illustrates the structural and genetic factors that contribute to the diagnostic challenges of biofilms:

Comparative Analysis of Diagnostic Approaches

Fundamental Limitations of Culture-Based Methods

Traditional culture methods face insurmountable challenges when confronting biofilm-associated infections. These techniques were designed for planktonic bacteria in their logarithmic growth phase, not for the complex, slow-growing, and heterogeneous communities found in biofilms [28]. The very process of sampling often fails to dislodge deeply embedded microorganisms, and the culture conditions cannot replicate the specific environmental requirements of all biofilm inhabitants [29].

Critical limitations include:

- Inadequate disaggregation: Standard processing may not effectively disperse biofilm clusters, resulting in underestimation of microbial diversity [28] [29].

- Non-cultivable organisms: Many bacteria within biofilms enter a viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state or have specific nutritional requirements not met by standard media [28].

- Selection bias: Routine culture media favor fast-growing species over slow-growing or anaerobic organisms, distorting the representation of the true microbial community [29].

- Polymicrobial oversight: In mixed infections, dominant species may overgrow and mask the presence of clinically significant co-infections [30] [29].

The Molecular Revolution in Biofilm Diagnostics

Molecular techniques bypass the need for cultivation, instead detecting microbial genetic material regardless of the physiological state of the organisms. These methods have revealed a startling disparity between what culture shows and the actual complexity of biofilm infections [28] [29].

Table 2: Methodological Comparison of Culture vs. Molecular Identification for Biofilm Diagnostics

| Parameter | Culture-Based Methods | Molecular Methods (16S rRNA Sequencing) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Low (detects ~1% of total microbiota) | High (theoretically a single copy of target DNA) |

| Time to Result | 24-72 hours (plus additional for identification) | 6-8 hours for PCR-DGGE; 24-48 hours for sequencing |

| Polymerobial Detection | Limited, often misses mixed communities | Excellent, specifically designed for complex mixtures |

| Required Bacterial Viability | Essential | Not required (detects viable, dead, and VBNC cells) |

| Quantification Capability | Quantitative (CFU/mL) | Semi-quantitative to quantitative (depending on method) |

| Species Identification Range | Limited to known, cultivable species | Broad, including uncultivated and novel species |

Quantitative Evidence: A Revealing Comparison

A landmark study comparing both methodologies across 168 chronic wounds demonstrated the dramatic superiority of molecular approaches. While culture methods identified only 17 different bacterial taxa, molecular identification using 16S rDNA sequencing revealed 338 different bacterial taxa in the same sample set [28]. This represents a 20-fold increase in microbial diversity detection with molecular methods.

Similarly, in urinary catheter-related samples, molecular techniques detected a significantly broader spectrum of microbes, including the emerging opportunistic pathogen Actinotignum schaalii, which was frequently missed by culture [29]. The same study reported that 86.1% of positive samples were polybacterial, far exceeding what routine culture could detect [29].

Experimental Protocols for Biofilm Analysis

Sample Processing and DNA Extraction Protocol

Effective biofilm analysis requires specialized sample processing to disrupt the EPS matrix and release embedded microorganisms:

Sonication Procedure:

- Place sample in 5 mL of Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth

- Perform two 5-minute sonication cycles interspersed with 2 minutes of vortexing [29]

- Centrifuge the sonication fluid and suspend the pellet in lysis buffer

DNA Extraction:

- Add sterile steel and glass beads to the sample

- Process in a TissueLyser at 30 Hz for 5 minutes for complete bacterial lysis

- Use commercial DNA extraction kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Mini Kit) following manufacturer's protocols

- Elute DNA in 30 μL water and dilute to a final concentration of 20 ng/μL [28]

16S rRNA Amplification and Sequencing

The molecular workflow for biofilm analysis typically follows these steps:

For 16S rRNA amplification:

- Use modified primers 28F (5′-GAGTTTGATCNTGGCTCAG-3′) and 519R (5′-GTTTACNGCGGCKGCTG-3′) to amplify a 500 bp region [28]

- For FLX-Titanium amplicon pyrosequencing, add linkers and barcodes to primers: 28F-A (5′-CCATCTCATCCCTGCGTGTCTCCGACTCAG-barcode-GAGTTTGATCNTGGCTCAG-3′) and biotinylated 519R-B [28]

- Perform PCR under optimized conditions for complex samples

Advanced Transcriptomic Analysis of Biofilms

For comprehensive understanding of biofilm gene expression, RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) with specialized bioinformatic tools can identify differentially expressed genes under various conditions. The scorecard method, a Python-based software tool, helps manage the heterogeneity of gene expression data across multiple experimental conditions by grouping genes based on relative fold-change and statistical significance [31]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying:

- Genes consistently up- or down-regulated across experiments

- Antibiotic resistance mechanisms

- Metabolic adaptations in biofilm phenotypes

- Virulence factors specific to biofilm mode of growth [31]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biofilm Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA Mini Kit | Efficient DNA extraction from complex biofilm matrices |

| PCR Reagents | Modified 16S primers (28F/519R) | Amplification of bacterial rRNA genes from mixed communities |

| Specialized Media | Wilkins-Chalgren Agar, BHI with supplements | Cultivation of fastidious and anaerobic biofilm organisms |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina MiSeq, Pyrosequencing | High-throughput analysis of microbial community composition |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Scorecard Python library, RipSeq Mixed | Analysis of complex transcriptomic and sequencing data |

| Disruption Reagents | Enzymatic matrix disruptors (dispersin B, DNase I) | EPS breakdown for improved microbial recovery |

| 6-Methylthioguanine-d3 | 6-Methylthioguanine-d3, MF:C6H7N5S, MW:184.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hydroxymethyl Clenbuterol-d6 | Hydroxymethyl Clenbuterol-d6, MF:C12H18Cl2N2O2, MW:299.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that traditional culture-based methods are inadequate for comprehensive analysis of biofilm-associated infections. The 20-fold higher detection rate of microbial diversity with molecular methods fundamentally changes our understanding of infectious diseases and explains why many chronic infections persist despite apparently negative culture results [28].

For researchers and clinicians, the implications are profound. Molecular techniques—particularly 16S rRNA sequencing and advanced transcriptomic approaches—provide unprecedented insights into the true complexity of biofilm communities [31] [29]. While culture retains value for antibiotic susceptibility testing and certain clinical scenarios, it should no longer be considered the gold standard for biofilm diagnosis.

The future of biofilm management lies in embracing these advanced molecular tools, developing standardized protocols for their implementation, and integrating their findings into therapeutic strategies. Only through this paradigm shift can we hope to effectively address the significant clinical challenges posed by biofilm-associated infections.

The field of clinical microbiology has undergone a profound transformation over the past century, moving from traditional culture-based methods grounded in Koch's postulates to modern genomic approaches that offer unprecedented resolution and speed. This paradigm shift represents not merely a technological upgrade but a fundamental change in how we detect, identify, and understand infectious diseases. The original Koch's postulates, formulated in the late 19th century, established a systematic framework for linking specific microorganisms to diseases through four criteria: consistent presence in disease, isolation in pure culture, disease reproduction in healthy hosts, and re-isolation from experimentally infected hosts [32] [33]. While these principles revolutionized medical microbiology, their limitations in addressing complex modern challenges have driven the development of molecular approaches that now complement and often surpass traditional methods [32].

The emergence of genomic medicine has introduced powerful new tools for pathogen identification, leveraging advances in DNA sequencing, bioinformatics, and computational analysis to transform diagnostic capabilities [34]. This shift has been particularly driven by the recognition that traditional methods struggle with unculturable organisms, polymicrobial infections, and the need for rapid results in clinical settings [35] [36]. The integration of genomic approaches has enabled researchers and clinicians to move beyond the constraints of Koch's original framework while preserving its core emphasis on establishing causal relationships between pathogens and disease [32].

Koch's Postulates: The Classical Framework

Original Principles and Historical Significance

Robert Koch's postulates, formulated in 1884, provided the first systematic methodology for establishing microbial pathogenesis [33]. The four original criteria required that:

- The microorganism must be found in diseased but not healthy individuals

- The microorganism must be cultured from the diseased individual

- Inoculation of a healthy individual with the cultured microorganism must recapitulate the disease

- The microorganism must be re-isolated from the inoculated, diseased individual [37] [33]

These principles created a rigorous experimental framework that allowed Koch and his contemporaries to definitively link specific bacteria to diseases such as anthrax and tuberculosis, marking the birth of modern infectious disease microbiology [32]. The postulates established causation standards that guided pathogen research for decades and remain foundational in medical education for developing scientific reasoning and diagnostic logic [32].

Limitations and Challenges

Despite their historical importance, Koch's postulates revealed significant limitations when applied to various infectious agents:

- Asymptomatic carriers: Koch himself discovered that asymptomatic individuals could carry Vibrio cholerae and Salmonella typhi, contradicting the first postulate's requirement that pathogens be absent in healthy hosts [37] [33]

- Unculturable organisms: Approximately 1% of bacterial species can be cultured using standard laboratory techniques, leaving many potential pathogens undetectable [32]

- Host-specific pathogens: Some microorganisms, such as Mycobacterium leprae and human-specific viruses, cannot infect available animal models, making it impossible to fulfill the third postulate [32] [33]

- Polymicrobial diseases: Many infections involve complex microbial communities where no single organism independently causes disease [32]

- Ethical constraints: Deliberate infection of human subjects to satisfy the third postulate raises significant ethical concerns [38] [33]

These limitations became increasingly apparent with the discovery of viruses, parasitic organisms with complex life cycles, and conditional pathogens whose disease manifestation depends on host factors [38] [32].

The Molecular Revolution: Transition to Genomic Medicine

Revised Postulates for Modern Microbiology

Recognizing the limitations of classical approaches, microbiologists have proposed various modifications to Koch's postulates:

Molecular Koch's postulates, introduced by Stanley Falkow in 1988, shifted focus from whole organisms to specific virulence genes [32] [33]. These criteria require that:

- The phenotype or property under investigation should be associated with pathogenic members of a genus or pathogenic strains of a species

- Specific inactivation of the gene(s) associated with the suspected virulence trait should lead to a measurable loss in pathogenicity or virulence

- Reversion or allelic replacement of the mutated gene should restore the pathogenicity [33]

Nucleic acid-based postulates proposed by Fredricks and Relman in 1996 emphasized sequence-based detection, requiring that a pathogen's nucleic acids be present in diseased tissues, correlate with disease development, and predictively align with known biological characteristics of related organisms [32].

For parasitic diseases, tailored postulates have been developed that account for complex life cycles, asymptomatic carriage, and host susceptibility factors [38]. These include requirements for consistent detection using validated methods, correlation with clinical symptoms, reproduction of disease in suitable animal models, and therapeutic response to anti-parasitic treatment [38].

Technological Drivers of the Paradigm Shift

The transition from traditional to genomic approaches has been fueled by revolutionary technological advances:

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms, particularly Illumina sequencing-by-synthesis, have dramatically reduced the cost of DNA sequencing while generating enormous datasets [39]. This "democratization of technology" has made large-scale genomic studies accessible to most research groups [39].

Third-generation sequencing technologies from Oxford Nanopore and Pacific Biosystems produce much longer reads (several to hundreds of kilobase pairs) and enable single-molecule sequencing without amplification [34].

Functional genomic tools including transposon insertion sequencing (Tn-seq) and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) methods allow genome-wide fitness profiling and targeted gene inactivation [39]. These approaches identify genes essential for bacterial survival under specific conditions, linking genes to important phenotypes like virulence and antibiotic resistance [39].

Table 1: Key Technological Advances Enabling Genomic Medicine

| Technology | Key Features | Applications in Microbiology |

|---|---|---|

| Next-generation sequencing (NGS) | High-throughput, massively parallel, reduced cost | Bacterial GWAS, strain typing, outbreak investigation |

| Third-generation sequencing | Long reads, single-molecule sequencing | Complete genome assembly, structural variation analysis |

| Tn-seq/TraDIS | Genome-wide fitness profiling | Essential gene identification, virulence factor discovery |

| CRISPRi | Targeted gene knockdown | Functional validation of virulence genes |

| Microarray/Ibis T5000 | Multiplex pathogen detection | Rapid identification of known pathogens |

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Molecular Methods

Methodological Principles and Workflows

Traditional culture-based methods and molecular genomic approaches operate on fundamentally different principles:

Traditional methods rely on phenotypic characteristics of microorganisms, including growth patterns, biochemical reactions, and morphological features [36]. The workflow typically involves specimen collection, culture on selective media, isolation of pure colonies, biochemical identification, and antimicrobial susceptibility testing [36]. This process requires viable organisms and can take 24-72 hours for preliminary results, with complete identification and susceptibility profiles requiring additional time [36].

Molecular methods target specific genomic sequences or molecular markers associated with pathogens [36]. Common workflows include nucleic acid extraction, amplification (e.g., PCR), and detection through various platforms [35] [36]. These approaches can provide results within hours, significantly reducing turnaround time compared to culture methods [36].

The following diagram illustrates the key workflows for both traditional and molecular diagnostic methods:

Figure 1: Comparative workflows of traditional culture-based versus molecular genomic diagnostic methods, highlighting significant differences in processing time and technique.

Performance Comparison in Clinical Settings

Multiple studies have directly compared the performance of traditional and molecular methods in clinical diagnostics:

A 2016 study on necrotizing soft tissue infections (NSTIs) demonstrated that molecular methods identified microorganisms in 90% of surgical samples, compared to 70% with culture-based methods [35]. Molecular approaches frequently detected additional microorganisms beyond those identified by culture, revealing greater microbial complexity in these infections [35].

In clinical microbiology laboratories, molecular methods have replaced culture for numerous applications including MRSA surveillance, gastrointestinal pathogen panels, Streptococcus pyogenes detection, Bordetella pertussis identification, and viral pathogen detection [36]. The transition has been driven by molecular methods' superior sensitivity and specificity, combined with significantly reduced turnaround times [36].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Traditional vs. Molecular Methods

| Parameter | Traditional Methods | Molecular Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Turnaround Time | 24-72 hours for preliminary results, 3-5 days for complete workup | Hours to 1 day |

| Sensitivity | Lower (depends on organism viability) | Higher (amplification enables detection of few copies) |

| Specificity | Lower (based on phenotypic characteristics) | Higher (based on genetic targets) |

| Viability Assessment | Yes (requires live organisms) | No (detects DNA from live and dead organisms) |

| Polymicrobial Detection | Challenging (may miss slow-growing organisms) | Excellent (multiple targets can be detected simultaneously) |

| Quantification | Possible (colony counts) | Limited on most platforms |

| Antimicrobial Susceptibility | Direct testing possible | Usually infers resistance from genetic markers |

| Cost | Lower | Higher |

Applications in Specific Clinical Scenarios

The complementary strengths of traditional and molecular methods make each suitable for different clinical scenarios:

Molecular methods excel in situations requiring rapid results that directly impact patient management. For example, meningitis/encephalitis panels can identify multiple pathogens within hours, enabling appropriate antibiotic selection when time is critical [36]. Similarly, gastrointestinal pathogen panels can simultaneously test for multiple bacterial, viral, and parasitic pathogens that would require separate cultures and staining procedures using traditional methods [36].

Traditional methods remain valuable when antimicrobial susceptibility testing is required, when dealing with organisms not covered by molecular panels, or when specimen quality may impact molecular test performance [36]. Culture also enables quantification of bacterial load, which can be clinically relevant in certain infections [36].

For complex infections like necrotizing soft tissue infections, the combined use of both methods provides the most comprehensive picture. Molecular methods offer rapid identification of likely pathogens, while culture provides isolates for susceptibility testing [35].

Genomic Medicine in Contemporary Research and Diagnostics

Advanced Genomic Applications

Genomic approaches have enabled sophisticated research methodologies that transcend traditional diagnostic capabilities:

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in bacteria use comparative genomics to identify genomic elements statistically associated with specific phenotypes or environmental conditions [39]. This approach has successfully identified candidate genes involved in host specificity, virulence, and antibiotic resistance across numerous bacterial species [39].

Whole-genome fitness profiling using transposon insertion sequencing (Tn-seq) identifies genes essential for bacterial survival under specific conditions by monitoring the frequency of transposon insertions across the genome [39]. This method has linked genes to metabolic pathways, stress response, antibiotic resistance, and virulence [39].

Bacterial GWAS approaches now incorporate quantitative trait variation, machine learning, and phylogenetic analyses to account for population structure and identify convergent evolution in divergent strains [39].

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Despite their advantages, genomic methods face implementation challenges:

Bioinformatic expertise is required for data analysis and interpretation, creating a barrier for some clinical laboratories [39] [34]. Solutions include user-friendly bioinformatics pipelines and increased training for laboratory personnel.

Cost considerations remain significant, particularly for comprehensive genomic analyses [34]. However, decreasing sequencing costs and the development of targeted panels make genomic approaches increasingly accessible.

Regulatory and standardization issues need addressing as molecular methods evolve rapidly compared to traditional approaches [36]. Ongoing efforts by regulatory agencies aim to produce updated guidelines addressing current laboratory practices and technical standards [36].

Data interpretation challenges arise from detecting multiple organisms or genetic markers of uncertain significance [35]. This requires correlation with clinical findings and appropriate stewardship of molecular testing.

Experimental Protocols and Research Applications

Key Methodologies in Genomic Microbiology

Bacterial Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS)

- Sample Collection: Hundreds of bacterial isolates from different environments or conditions [39]

- Genome Sequencing: Whole-genome sequencing using NGS platforms [39]

- Variant Identification: Detection of SNPs, k-mers, or accessory genetic elements [39]

- Association Analysis: Statistical testing for genetic elements associated with phenotypes, accounting for population structure [39]

- Validation: Functional validation of candidate genes through mutagenesis or other experimental approaches [39]

Transposon Insertion Sequencing (Tn-seq)

- Library Construction: Generation of comprehensive transposon insertion mutants [39]

- Selection Pressure: Growth under defined in vitro or in vivo conditions [39]

- DNA Preparation: Amplification and sequencing of transposon-genome junctions [39]

- Data Analysis: Mapping insertion sites and calculating fitness coefficients [39]

- Hit Identification: Statistical identification of genomic regions with significantly fewer insertions (essential genes) [39]

Metagenomic Sequencing for Pathogen Detection

- Sample Processing: Direct DNA extraction from clinical samples without culture [35]

- Library Preparation: Fragmentation, adapter ligation, and amplification [34]

- Sequencing: High-throughput sequencing on platforms such as Illumina or Oxford Nanopore [39] [34]

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Taxonomic classification using reference databases [35]

- Pathogen Identification: Correlation of abundance with clinical findings [35]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Microbiology

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples/Applications |

|---|---|---|

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Prepare DNA fragments for sequencing | Illumina Nextera, NEBNext Ultra |

| Transposon Mutagenesis Systems | Generate comprehensive mutant libraries | Himar1 mariner transposon, EZ-Tn5 |

| CRISPR Interference Systems | Targeted gene knockdown | dCas9-sgRNA complexes for bacterial gene repression |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing Reagents | Microbial community profiling | Primers targeting hypervariable regions, clone libraries |

| Whole Genome Amplification Kits | Amplify limited DNA samples | MDA (Multiple Displacement Amplification) |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Analyze sequencing data | SPAdes (genome assembly), Bowtie2 (read alignment), DESeq2 (differential abundance) |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolate DNA from complex samples | Soil, stool, and tissue DNA extraction kits |

| Selective Culture Media | Traditional isolation of pathogens | Chromogenic media for specific pathogen identification |

| 3-epi-Ochratoxin A-d5 | 3-epi-Ochratoxin A-d5|Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard | 3-epi-Ochratoxin A-d5 is a deuterium-labeled internal standard for precise Ochratoxin A quantification in research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Midazolam 2,5-Dioxide-d6 | Midazolam 2,5-Dioxide-d6, CAS:1215321-98-4, MF:C18H13ClFN3O2, MW:363.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of genomic approaches into clinical microbiology continues to accelerate, driven by ongoing technological advances and decreasing costs. Third-generation sequencing technologies are producing longer reads that improve genome assembly and enable detection of structural variations [34]. The application of machine learning and artificial intelligence to genomic datasets promises to enhance pattern recognition and predictive modeling for outbreak investigation and transmission tracking [39].

The concept of "reverse microbial etiology" exemplifies the paradigm shift from reactive to proactive approaches [32]. Rather than waiting for disease outbreaks to identify pathogens, this approach establishes pathogen warning systems through ongoing environmental surveillance [32]. This aligns with the transition in healthcare from treatment-centered models to comprehensive frameworks integrating prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and health maintenance [32].

The complementary relationship between traditional and molecular methods will likely continue evolving. While molecular approaches offer unprecedented speed and resolution, traditional culture methods remain essential for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, outbreak investigation, and understanding the biological characteristics of pathogens [36]. The future of clinical microbiology lies not in complete replacement of traditional methods but in their strategic integration with genomic approaches to provide comprehensive diagnostic capabilities.

In conclusion, the shift from Koch's postulates to genomic medicine represents a fundamental transformation in how we detect and understand infectious diseases. While Koch's principles established crucial foundational standards for establishing causation, modern genomic approaches have overcome their limitations through molecular detection, sophisticated analysis, and rapid diagnostics. This paradigm shift has expanded our view of host-pathogen interactions, revealed previously unrecognized microbial complexity, and provided powerful new tools for clinical diagnostics and public health. As genomic technologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly uncover new dimensions of microbial pathogenesis while further transforming the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of infectious diseases.

Methodological Approaches and Real-World Applications in Clinical and Research Settings

For over a century, microbial culture has served as the fundamental cornerstone of microbiological diagnosis, providing the benchmark for detecting and identifying pathogens [40]. However, contemporary diagnostic laboratories are increasingly navigating a paradigm shift, integrating or substituting traditional culture-based methods with advanced molecular techniques [40]. This transition is driven by the recognition of well-documented limitations inherent in culture, including prolonged turnaround times, intensive labor requirements, and the frequent failure to identify difficult-to-culture or fastidious microorganisms [41] [40]. Molecular diagnostics (MDx), particularly nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), offer a compelling alternative with superior speed, sensitivity, and specificity [40].

This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these methodologies, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of culture-based versus molecular method research. It is designed to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the empirical evidence and procedural knowledge necessary to select the optimal technique for their specific sample type and microbial target.

Performance Comparison: Culture vs. Molecular Diagnostics

Extensive head-to-head studies across various clinical scenarios consistently demonstrate the enhanced sensitivity and efficiency of molecular methods compared to traditional culture. The following table summarizes quantitative performance data from recent comparative studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Culture vs. Molecular Diagnostics

| Study & Sample Type | Target Pathogen(s) | Method | Sensitivity | Key Performance Findings | Turnaround Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Podiatric Wound Infections [41] | Polymicrobial pathogens (S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, etc.) | Traditional Culture | Reference | Underdetected ~30% of clinically significant pathogens found by PCR. | Several days |

| Real-time PCR Panel | 98.3% (vs. culture) | Detected 110 significant pathogens missed by culture; high sensitivity in polymicrobial wounds. | Significantly faster (specific time not given) | ||

| CPGNB Rectal Swabs [3] | Carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacilli | Culture-based (ChromID CARBA SMART) | 64.8% | Required substantial hands-on time (~90 minutes). | Lengthy (includes incubation) |

| Direct Molecular (Xpert Carba-R) | 90.2% | Superior sensitivity; minimal hands-on time (~1.3 minutes). | ~1 hour (hands-on time) | ||

| Campylobacter Enteritis [40] | Campylobacter species | Culture | 51.2% | Difficulties due to fastidious growth requirements. | Up to 10 days |

| PCR | 100% (relative to PCR-positive) | Significantly superior sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value. | Within a day | ||

| Urinary Tract Infections [40] | Polymicrobial infections | Urine Culture | 22% | Poorly detects polymicrobial infections. | 24-48 hours |

| Multiplex PCR | 95% | Significantly more sensitive for detecting co-infections. | Within a day |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

This protocol is designed for a year-long, large-scale comparison study in a moderate-prevalence setting.

- Sample Type: Rectal swabs from patients.

- Sample Collection & Processing:

- Collect swabs and process for both culture and molecular methods from the same specimen.

- Culture-Based Method:

- Inoculation: Plate the sample onto chromID CARBA SMART selective agar.

- Incubation: Incubate plates under appropriate conditions to isolate Gram-negative bacilli.

- Confirmation: Perform conventional PCR on isolated colonies to confirm the presence of carbapenemase genes.

- Inclusion of NFGNB: The study emphasized including non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli (NFGNB) in the analysis, which significantly increased the sensitivity of the culture strategy from 46.3% to 64.8%.

- Direct Molecular Method:

- Testing: Use the Cepheid Xpert Carba-R assay directly from the specimen.

- Procedure: Follow manufacturer's instructions for nucleic acid extraction, amplification, and detection of carbapenemase genes.

- Reference Standard: A composite reference standard was used, where detection by either method was considered a true positive.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate sensitivity for each method against the reference standard.

- Measure hands-on technologist time for both methods.

- Track potential patient contact precautions averted by faster, more sensitive molecular results.

This protocol uses a dual-swab approach to minimize sampling variability for a direct comparison.

- Sample Type: Dual-swab specimens from clinical wound cases (e.g., diabetic foot ulcers, pressure ulcers).

- Sample Collection:

- Collect two swabs from the same wound site simultaneously.

- Culture-Based Testing:

- Processing: Send one swab to a commercial reference laboratory for standard culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST).

- Gram Stain: Review Gram stain results for morphological features (e.g., Gram-positive cocci, Gram-negative rods).

- Molecular Testing (Real-time PCR):

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract from the second swab using the MagMAX Microbiome Ultra Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit on a mechanical bead-based lysis system (e.g., Omni Bead Ruptor Elite).

- PCR Amplification & Detection: Perform real-time PCR using a nanoscale SmartChip Real-Time PCR System with TaqMan assays targeting a comprehensive panel of bacterial and fungal pathogens, plus antibiotic resistance genes.

- Statistical Analysis:

- Concordance: Calculate organism-level concordance.

- Diagnostic Metrics: Determine sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, accuracy, and F1 score using culture as the initial reference.