Controlling Spatial Variation in Microbial Sampling: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Research and Drug Development

Spatial variation is a fundamental, yet often overlooked, factor that can significantly impact the reproducibility and interpretation of microbial studies.

Controlling Spatial Variation in Microbial Sampling: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Research and Drug Development

Abstract

Spatial variation is a fundamental, yet often overlooked, factor that can significantly impact the reproducibility and interpretation of microbial studies. This article provides a systematic framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to understand, control, and account for spatial heterogeneity in microbial communities. We explore the ecological drivers of spatial patterns across diverse environments—from the human gut to deep-sea trenches—and detail advanced methodologies for robust sampling design. The guide further addresses troubleshooting for technical noise and validation techniques to distinguish true biological signals from spatial artifacts. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with practical applications, this resource aims to enhance the accuracy and reliability of microbiome research, thereby strengthening downstream analyses in drug discovery and clinical diagnostics.

Why Space Matters: Unraveling the Drivers of Microbial Spatial Heterogeneity

Spatial variation refers to the differences in microbial community structure, function, and abundance across different physical scales and locations. Understanding these patterns is crucial for research reproducibility, accurate ecological interpretation, and pharmaceutical quality control. Spatial heterogeneity exists across a continuum, from macro-scale variations across kilometers in marine environments to micro-scale gradients within millimeters in host-associated or soil habitats.

The following troubleshooting guides and FAQs address the specific methodological challenges researchers face when controlling for spatial variation in their experimental designs, providing practical solutions to enhance data quality and reliability.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: How does spatial scale impact microbial community analysis?

Answer: The impact of spatial scale is profound and varies significantly across ecosystems:

- Marine Environments: In the Bohai Sea, distinct temporal-spatial zones emerged in sediments between June and August, characterized by significant differences in dissolved oxygen, bottom water acidification, and nutrient concentrations (TN, NO₃â», PO₄³â», DOC). These spatial and temporal variations strongly influenced microbial community composition, with August conditions triggering a significant decline in aerobic bacteria and an increase in anaerobes [1].

- Freshwater Reservoirs: Research on Zhangjiayan Reservoir sediments demonstrated that bacterial communities exhibited significantly distinct clustering patterns between spring/summer and autumn/winter seasons (P < 0.05). Both diversity indices and taxonomic abundance were markedly higher during spring and summer compared to autumn and winter periods [2].

- Human Skin: The cutaneous microbiome varies not only between individuals but also between different body sites on the same individual according to local skin properties (e.g., oily, moist, dry) [3].

- Rhizosphere: In the maize rhizosphere, enzymatic activity and microbial growth kinetics show dramatic gradients at sub-millimeter scales. Active microbial biomass was up to 29 times greater at <2 mm from the root compared to >2 mm, and the lag-time before microbial growth was 0.5 hours shorter in this near-root zone [4].

Table 1: Spatial Variation Across Ecosystems

| Ecosystem | Spatial Scale | Key Observed Variations | Dominant Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marine (Bohai Sea) | Kilometers to meters | Distinct temporal-spatial zones in sediments; shifts in aerobic/anaerobic ratios | Dissolved oxygen, temperature, TN, PO₄³â», DOC [1] |

| Freshwater Reservoir | Basin scale | Significant seasonal clustering; higher spring/summer diversity | DO, SRP, sediment pH, phosphorus, ALP, TOC [2] |

| Rhizosphere | Sub-millimeter | 29x greater active biomass at <2mm vs >2mm; different enzyme activities | Root exudate gradients, microbial growth kinetics [4] |

| Human Skin | Body regions to centimeters | Distinct microbial communities by skin characteristics | Temperature, pH, humidity, sebum production [3] |

FAQ 2: What sampling strategies best capture spatial variation at micro-scales?

Answer: Capturing micro-scale variation requires specialized approaches:

High-Resolution Sampling: For rhizosphere studies, traditional destructive sampling often lacks the sensitivity to accurately reflect spatial gradients. Research demonstrates that 1 mm resolution sampling reveals significant rhizosphere gradients in microplate assays, particularly for β-glucosidase, with a gradual decrease in Vmax at 1–2 mm (up to 1.7 times) and >2 mm (up to 4.5 times) compared to <1 mm [4]. This highlights the critical need for short-distance sampling techniques to accurately capture spatial distribution.

Standardized Swab Selection: For cutaneous microbiome sampling:

- Swab Type Matters: Flocked nylon swabs (eSwabs) yield significantly higher biomass (average 22.48 ng) compared to cotton swabs (average 5 ng) [3].

- Minimal Effect Factors: Moistening solution (saline vs. PBS), swabbing duration (30 sec vs. 1 min), and immediate storage conditions (room temperature vs. -80°C) did not significantly affect total DNA yield or microbiome profiling [3].

- Individual Variability: Data clustering is affected more by individual subject than by sampling conditions, highlighting the importance of accounting for inter-individual variability in study design [3].

Table 2: Optimized Sampling Methods for Different Habitats

| Habitat | Recommended Method | Spatial Resolution | Key Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhizosphere | High-resolution destructive sampling | <1 mm intervals | β-glucosidase activity shows 1.7x decrease at 1-2mm, 4.5x at >2mm [4] |

| Cutaneous Microbiome | Flocked nylon swabs (eSwabs) | Single body site | Higher biomass yield (avg 22.48 ng vs 5 ng for cotton); moistening solution has minimal effect [3] |

| Aquatic Sediments | Box corer with stratified sampling | Centimeter layers | Seasonal variations significant; collect across multiple seasons [1] [2] |

| Water Column | Depth-stratified hydrophore | Meter intervals | Consider thermal and oxygen stratification, especially in sub-deep reservoirs [2] |

FAQ 3: How can I neutralize antimicrobial properties in samples for accurate microbial testing?

Answer: Pharmaceutical products with inherent antimicrobial activity require careful neutralization for accurate microbial testing:

- Dilution Approach: For 18 of 40 challenging finished products, neutralization was achieved through 1:10 dilution with diluent warming. Another 8 products with no inherent antimicrobial activity from their API were neutralized through dilution and the addition of 1-5% Tween 80 [5].

- Filtration Methods: For 13 products (mostly antimicrobial drugs), neutralization required variations of different dilution factors and filtration with different membrane filter types with multiple rinsing steps [5].

- Validation Essential: Method suitability must be verified using standard strains (Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Aspergillus brasiliensis, Burkholderia cepacia complex, Candida albicans) with acceptable microbial recovery of at least 84% for all strains with proper neutralization methods [5].

FAQ 4: What advanced technologies can enhance spatial analysis in microbial studies?

Answer: Several emerging technologies offer significant advantages:

- Spectral Flow Cytometry: Enables high-dimensional analysis with unprecedented deep phenotyping and more precise cell characterization. This technology uses multiple detectors to capture the entire fluorescence emission spectrum for each fluorochrome, allowing more precise signal unmixing and simultaneous analysis of a greater number of parameters (up to 50 markers) within a single tube [6].

- High-Dimensional Cytometry Data Analysis: Tools like cyCONDOR provide comprehensive computational frameworks covering essential steps of cytometry data analysis, including guided pre-processing, clustering, dimensionality reduction, and machine learning algorithms. This facilitates integration into clinically relevant settings where scalability is paramount [7].

- Integrated Multi-Omics Approaches: Combining high-dimensional cytometry with other data types through advanced analytical platforms allows for more comprehensive understanding of microbial systems in their spatial context [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Spatial Variation Studies

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tween 80 (Polysorbate 80) | Neutralizing agent for antimicrobial products | Microbial quality control of pharmaceuticals | Used at 1-5% concentration; effective for products without inherent API antimicrobial activity [5] |

| Lecithin | Neutralizing agent | Microbial quality control | Used at 0.7% concentration in combination with other neutralizers [5] |

| eSwabs (flocked nylon) | Sample collection | Cutaneous microbiome studies | Yield higher biomass (avg 22.48 ng) vs cotton swabs (avg 5 ng) [3] |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Moistening solution for swabs | Cutaneous microbiome sampling | No significant difference vs saline in DNA yield or community profiling [3] |

| Soybean-Casein Digest Agar (SCDA) | Total aerobic microbial count | Pharmaceutical quality control | For TAMC; bacterial colonies on fungal media counted as part of TAMC [5] |

| Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) | Total yeast and mold count | Pharmaceutical quality control | For TYMC; fungal colonies on this medium specifically counted [5] |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

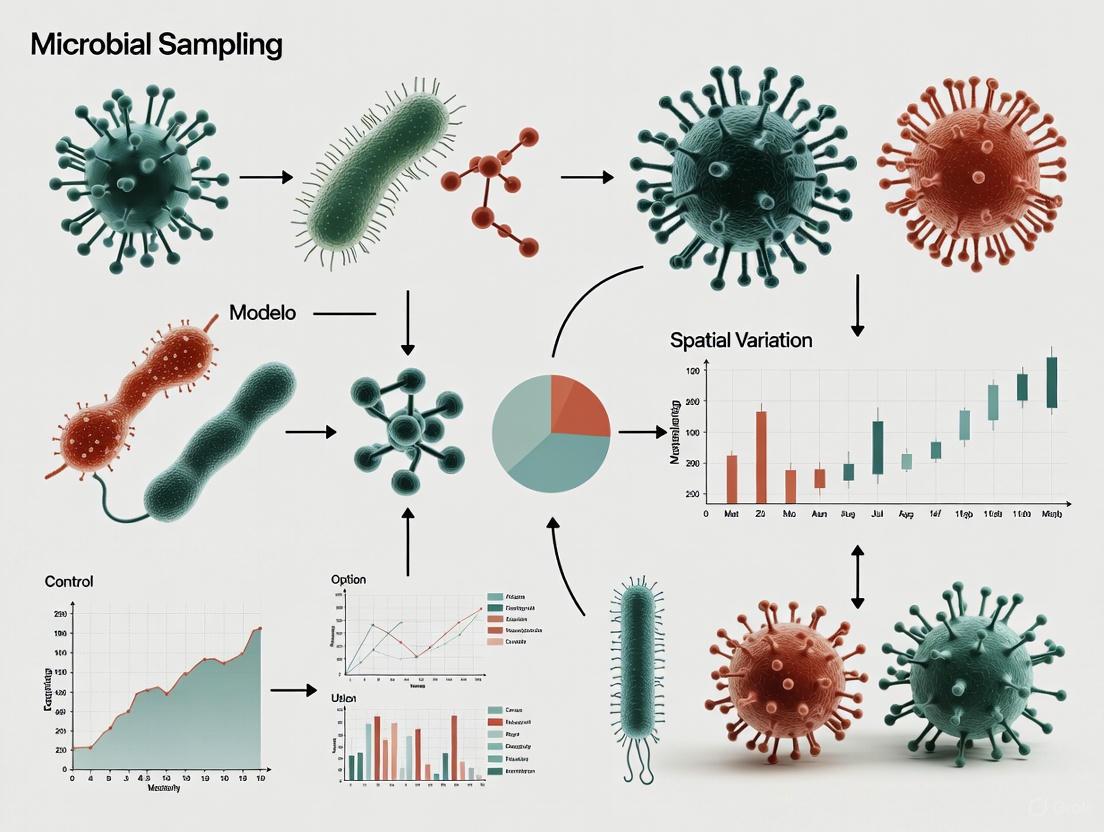

Diagram 1: Microbial Sampling Strategy Selection Workflow

Diagram 2: Pharmaceutical Microbial QC Neutralization Strategy

Frequently Asked Questions: Troubleshooting Microbial Sampling

Q1: My microbial community analysis shows unexpected spatial variation. What are the primary environmental factors I should investigate? Your findings are likely driven by key environmental drivers. Research consistently shows that temperature and nutrients (particularly total phosphorus and nitrogen forms) are dominant factors [8] [1] [9]. In a tropical reservoir, temperature and total phosphorus were the most significant variables affecting the community composition of both archaea and bacteria [8]. Similarly, in mountain stream sediments, temperature was found to influence bacterial community structure through both direct and indirect pathways by altering sediment parameters [9]. You should also analyze a suite of physicochemical factors like dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, and oxidation-reduction potential (ORP), as these create gradients that shape microbial niches [8] [1].

Q2: How can I design a sampling plan to accurately capture spatial variation in a heterogeneous environment? A robust sampling design is critical. A recent study on avocado orchards demonstrated that the chosen sampling design (grid-based, longitudinal transect, or zigzag transect) can directly influence the observed bacterial community composition and the identified key edaphic drivers [10]. For the most reliable characterization of microbial communities, the study recommends a random, grid-based sampling design as a simple and effective method [10]. This approach helps ensure that your data is representative and not skewed by the sampling methodology itself.

Q3: I've detected temporal changes in my microbial data. Is this normal, and what causes it? Yes, this is expected and often significant. Microbial communities exhibit strong temporal dynamics in response to environmental changes [8] [1]. For example, in the Bohai Sea, the microbial community in August was distinctly different from that in June, characterized by lower dissolved oxygen and higher concentrations of nutrients like TN, NO₃â», and PO₄³⻠[1]. In the Songtao Reservoir, microbial diversity indices (Chao1, Shannon, Simpson) were significantly higher in winter than in summer, and the overall structural composition showed clear seasonal differences [8]. Always record key parameters like temperature and nutrient levels at the time of sampling to contextualize temporal shifts.

Q4: My sample recovery for Gram-negative bacteria is low. What could be going wrong? This is a common methodological challenge. During aerosolization or when a culture medium surface loses moisture, Gram-negative bacteria are particularly susceptible to desiccation damage [11]. This can cause irreversible damage to the cell structure and lead to loss of viability. To mitigate this, ensure your sampling protocols minimize desiccation, for instance, by using appropriate neutralizers in your dilution reagents and by ensuring that agar plates do not dry out during incubation [11].

The following table synthesizes quantitative findings on key environmental drivers from recent studies.

| Environmental Driver | Measured Parameters | Observed Impact on Microbial Community | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature [8] [9] | Water temperature (°C) | Directly and indirectly (via sediment parameters) alters bacterial community structure; a key driver of spatiotemporal variation [8] [9]. | Tropical Reservoir & Mountain Stream |

| Nutrients: Phosphorus [8] [1] | Total Phosphorus (TP), Phosphate (PO₄³â») | Significantly correlates with microbial species abundance; major contributor to community composition shifts and temporal zonation [8] [1]. | Tropical Reservoir & Coastal Sea |

| Nutrients: Nitrogen [1] | Total Nitrogen (TN), Nitrate (NO₃â»), Ammonia (NHâ‚„âº) | Increased concentrations linked to a decline in aerobic bacteria, an increase in anaerobes, and accumulation of ammonia-/nitrite-oxidizing bacteria [1]. | Coastal Sea |

| Physicochemical: DO & pH [1] | Dissolved Oxygen (DO), pH | Low DO and pH in bottom sediment created a distinct temporal zone, favoring anaerobic metabolic pathways [1]. | Coastal Sea |

| Metals [8] | Selenium (Se), Nickel (Ni) | Abundance of microbial species showed significant correlation with concentrations of Se and Ni [8]. | Tropical Reservoir |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Water Column and Sediment Sampling for Microbial Community Analysis

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in reservoir and marine studies [8] [1].

- Site Selection: Establish sampling sites strategically to cover gradients (e.g., upstream, midstream, downstream) or areas of interest. A grid-based design is recommended for heterogeneous environments [8] [10].

- In-Situ Physicochemical Measurement: At each site, use a multi-parameter sonde (e.g., YSI Pro Plus) to measure temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), electrical conductivity (EC), and turbidity directly in the field [8] [1].

- Water Sample Collection:

- Collect water samples using a hydrophore or sterile glass bottles [1].

- For microbial analysis, filter a known volume of water (e.g., 1-2 L) through a 0.22 μm membrane filter. Store filters at -80°C until DNA extraction [8] [1].

- For nutrient/metal analysis, collect additional water samples, transport them to the lab at 4°C, and filter through 0.45 μm membranes. Analyze for Total Nitrogen (TN), Total Phosphorus (TP), COD, and metals (e.g., Cr, Mn, Ni, Cu, Se, Cd, Ba) using standard spectrophotometric and ICP-MS methods [8].

- Sediment Sample Collection:

- Collect sediment using a Peterson dredger or box corer [1] [9].

- For microbial DNA, place subsamples in sterile bags and flash-freeze on dry ice for transport [9].

- For sediment physicochemical analysis, collect separate subsamples. Air-dry, grind, and analyze for Total Carbon (TC), Total Nitrogen (TN), Total Phosphorus (TP), and Organic Matter (OM) [9].

Protocol 2: Microbial DNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Bioinformatics

- DNA Extraction: Extract total genomic DNA from filters or sediment (e.g., 0.5 g) using the CTAB or SDS method [8] [9].

- 16S rRNA Gene Amplification: Amplify the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene using primers 341F and 806R [8] [9].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare libraries using a kit like the Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation Kit and sequence on an Illumina platform (e.g., NovaSeq) [8] [1].

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- Statistical Analysis:

- Calculate alpha-diversity indices (Chao1, Shannon, Simpson).

- Perform Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) for beta-diversity.

- Use Redundancy Analysis (RDA) and Mantel's test to link community variation to environmental factors [8].

Experimental Workflow and Factor Relationships

Diagram 1: Microbial sampling and analysis workflow.

Diagram 2: Environmental factor relationships.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Membrane Filters (0.22 μm & 0.45 μm) | For concentrating microbial cells from water samples (0.22 μm) and filtering water for physicochemical analysis (0.45 μm) [8] [1]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits (CTAB/SDS method) | For extracting high-quality metagenomic DNA from complex environmental samples like water filters and sediment [8] [9]. |

| Primers 341F & 806R | Universal prokaryotic primers for amplifying the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene for Illumina sequencing [8] [9]. |

| TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Library Prep Kit | Used for preparing high-quality sequencing libraries without PCR bias, suitable for metagenomic studies [8] [1]. |

| Multi-Parameter Sonde (e.g., YSI Pro Plus) | For in-situ measurement of critical physicochemical parameters: temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), salinity, etc. [8] [1]. |

| Culture Media (TSA, MEA, SDA) | For viable air monitoring and cultivation; TSA for bacteria, MEA/SDA for yeast and mold [12]. |

| ICP-MS Calibration Standards | For accurate quantification of metal concentrations (e.g., Se, Ni) in water samples, which can be key drivers of microbial composition [8]. |

| Palmitoleyl linolenate | Palmitoleyl linolenate, MF:C34H60O2, MW:500.8 g/mol |

| 5-Methyl-3-oxo-4-hexenoyl-CoA | 5-Methyl-3-oxo-4-hexenoyl-CoA, MF:C28H44N7O18P3S, MW:891.7 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guide: Controlling for Spatial Variation

Problem: High variability and inconsistent results between samples. Spatial variation is a major confounder in gut microbiome and host biology studies. The table below outlines common issues and evidence-based solutions to control for this variability.

| Problem & Symptom | Root Cause | Solution & Recommended Action | Key Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High variance in bacterial abundance measurements; inability to distinguish true temporal shifts from spatial heterogeneity. | Single samples per time point conflating spatial sampling noise with genuine temporal dynamics. | Implement the DIVERS (Decomposition of Variance Using Replicate Sampling) protocol: collect two spatial replicates per time point; use spike-in controls for absolute abundance quantification [13]. | [13] |

| Inconsistent transcriptional profiles; failure to replicate defined metabolic domains along the gut axis. | Sampling from undefined or inconsistent intestinal regions (e.g., treating "colon" as a single unit). | Define sampling strategy by the five discrete metabolic domains of the small intestine or the distinct immune-stromal neighborhoods of the colon. Use machine learning models to verify domain identity where possible [14] [15]. | [14] [15] |

| Inability to detect genuine biological gradients; data is dominated by technical noise. | Technical noise from library preparation and sequencing obscuring true biological signal, especially for low-abundance taxa/transcripts. | Use spike-in controls (for metagenomics) or UMI-based single-cell/nuclei protocols (for transcriptomics). Filter out taxa/genes where technical noise contributes >50% to total variance [13]. | [13] |

| Confounding spatial organization with cell type composition; unclear if a signal is from a new cell type or spatial reorganization. | Analytical methods that do not preserve spatial context, relying solely on dissociated cells. | Employ spatial transcriptomics (ST) or multiplexed imaging (CODEX). These technologies allow for the mapping of gene expression and cell types directly within the tissue architecture [16] [15]. | [16] [15] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is it critical to move beyond the traditional three-segment model of the small intestine in my sampling design? Recent high-resolution studies have revealed that the mouse and human small intestine is organized into five discrete metabolic domains with distinct transcriptional profiles and nutrient absorption functions [14]. Sampling based only on the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum can miss critical biological variation, as these domains have indefinite borders and may not reflect the underlying metabolic zonation. Defining your sampling strategy by these domains provides a more precise and biologically relevant framework.

2. How can I quantitatively determine what portion of my data variance is due to spatial sampling noise versus true temporal changes? The DIVERS variance decomposition model is designed specifically for this purpose. It uses replicate sampling and spike-in sequences to provide a principled mathematical breakdown of variance. The model separates the contributions of temporal dynamics, spatial sampling variability, and technical noise to the total variance of each bacterial taxon or host gene [13].

3. What are the key spatial differences in the large intestine (colon) that I should account for? The colon exhibits significant spatial organization in its cellular composition and immune niches. Key differences include [15]:

- A decrease in CD8+ T cells and an increase in dendritic cells from the ascending to the sigmoid colon.

- An increase in smooth muscle cells and a decrease in endothelial cells compared to the small intestine.

- The presence of distinct stromal and immune multicellular neighborhoods, such as a Plasma-Cell-Enriched neighborhood.

4. Which experimental techniques are best for preserving spatial information in gut studies?

- For transcriptomics: Spatial Transcriptomics (ST) allows for genome-wide expression profiling directly on tissue sections, preserving the spatial context of the liver lobule or intestinal crypt-villus axis [16].

- For cell typing and mapping: Multiplexed imaging (e.g., CODEX) uses antibody panels to visualize and quantify dozens of cell types simultaneously within their native tissue architecture, revealing cellular neighborhoods and communities [15].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: DIVERS for Quantifying Spatiotemporal Variation in Microbial Communities

This protocol quantifies the sources of variability in longitudinal microbiome studies [13].

- Sample Collection: At each time point in a longitudinal study, collect two replicate samples from randomly chosen spatial locations within the same stool specimen or gut region.

- Spike-in and Technical Replication: Take one of the two spatial replicates and split it in half to create two technical replicates.

- Spike-in Addition: Add a known quantity of a spike-in strain (not native to the gut community) to all samples during DNA extraction. This allows for the calculation of absolute abundances, correcting for compositional artifacts.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Perform 16S rRNA gene sequencing or whole-metagenome shotgun sequencing. Use the DIVERS statistical model to decompose the variance and covariance of absolute abundances into temporal, spatial, and technical components.

Protocol 2: Spatial Mapping of Intestinal Cell Communities via Multiplexed Imaging

This protocol details the steps for mapping cellular organization in intestinal tissues [15].

- Tissue Preparation: Collect intestinal samples from defined regions (e.g., duodenum, ileum, ascending colon). Embed and cryosection fresh-frozen tissue sections.

- Antibody Staining: Stain the tissue sections with a validated panel of ~50 antibodies using the CODEX multiplexed imaging platform. The panel should include markers for epithelial, stromal, and immune cell lineages.

- Image Acquisition and Processing: Image the stained tissue sections. Process the images to perform single-cell segmentation and assign cell types based on antibody staining patterns.

- Neighborhood Analysis: Use graph-based clustering algorithms on the single-cell data to identify significant multicellular neighborhoods—groups of cells that consistently co-localize across tissue samples.

Summarized Quantitative Data

Table 1: Variance Decomposition of Abundant Gut Microbiota (DIVERS Analysis) Data from a high-resolution human fecal time series shows the average percentage contribution of different factors to total abundance variance for operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with mean absolute abundance > 10â»â´ [13].

| Variability Source | Average Contribution to Variance |

|---|---|

| Temporal Dynamics | ~55% |

| Spatial Sampling | ~20% |

| Technical Noise | ~25% |

Table 2: Shift in Key Cell Type Percentages from Small Intestine to Colon Data derived from multiplexed imaging (CODEX) of human intestinal sections, showing changes in the relative abundance of major cell types [15].

| Cell Type | Trend from Small Intestine to Colon |

|---|---|

| CD8+ T cells | Decrease |

| Dendritic cells | Increase |

| Smooth muscle cells | Increase |

| Endothelial cells | Decrease |

| Enterocytes | Decrease |

| Goblet cells | Increase |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Spike-in Control (e.g., non-gut bacterium) | Added in known quantities before DNA extraction to convert relative sequencing abundances to absolute abundances, critical for accurate variance decomposition [13]. |

| Validated Antibody Panel for CODEX | A panel of ~50 antibodies against epithelial, stromal, and immune markers for multiplexed tissue imaging to identify cell types and spatial neighborhoods without dissociation [15]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics (ST) Array | A glass slide with arrayed barcoded oligo spots for performing spatial transcriptomics, capturing genome-wide gene expression data from intact tissue sections [16]. |

| Machine Learning Classifier | A computational model trained on domain-specific gene expression data to systematically identify and verify intestinal domain identity in new samples [14]. |

| Methyl 3-hydroxyheptadecanoate | Methyl 3-hydroxyheptadecanoate, MF:C18H36O3, MW:300.5 g/mol |

| 2,4-dimethylhexanedioyl-CoA | 2,4-dimethylhexanedioyl-CoA, MF:C29H48N7O19P3S, MW:923.7 g/mol |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Spatial Analysis Workflow

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: My sediment profile data shows unexpected heterogeneity. How can I distinguish true spatial variation from technical noise?

- Problem: Fluctuations in measured parameters (e.g., bacterial abundances, carbon content) across depth can be caused by genuine spatial heterogeneity, temporal changes, or technical artifacts from sample processing and sequencing.

- Solution: Implement a replicate sampling design and use statistical decomposition methods.

- Recommended Protocol: The DIVERS (Decomposition of Variance Using Replicate Sampling) method quantifies these sources of variation [13].

- Collect two spatial replicate samples from randomly chosen locations at each sampling point (e.g., different cores from the same depth horizon).

- Split one of the spatial replicates to create two technical replicates.

- Use a spike-in procedure during sample processing to enable absolute abundance measurements.

- Apply the DIVERS variance decomposition model to mathematically separate the contributions of time, spatial sampling location, and technical noise to your total measured variance [13].

- Application: In a study of human gut microbiome spatial variation, this method revealed that nearly half of the detected taxa were dominated by technical noise, while for abundant taxa, spatial sampling heterogeneity contributed about 20% to the total variance [13].

FAQ 2: Traditional sediment stratification is slow and laborious. Are there rapid, high-resolution alternatives?

- Problem: Manually identifying and characterizing physical and chemical layers in sediment cores is inefficient and can miss subtle transitions [17].

- Solution: Utilize Visible and Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (VNIR) combined with machine learning.

- Recommended Protocol: As demonstrated in a study of a South China Sea sediment core [17]:

- Sample Preparation: Segment the core at fine intervals (e.g., 1 cm). Freeze-dry, grind, and sieve the samples.

- Spectral Data Collection: Use a spectrophotometer (e.g., Agilent Cary 5000) with a diffuse reflectance module to collect VNIR spectra for each sample.

- Data Processing & Modeling: Preprocess spectra (e.g., Savitzky–Golay filtering). Use algorithms like Competitive Adaptive Reweighted Sampling (CARS) to identify characteristic wavelengths. Train a classification model, such as a Support Vector Machine (SVM), to predict sediment layers. Combining unsupervised clustering (e.g., K-means, Density Peak Clustering) with SVM can achieve correct classification rates over 94% [17].

- Recommended Protocol: As demonstrated in a study of a South China Sea sediment core [17]:

FAQ 3: How can I map sedimentary carbon distribution over a large area without exhaustive sampling?

- Problem: Point measurements from sediment grabs provide limited spatial representation, making it difficult to identify carbon hotspots and estimate total stocks accurately [18].

- Solution: Employ an integrated approach using seafloor acoustics, imagery, and ground-truthing.

- Recommended Protocol: A study in Loch Creran, Scotland, successfully used this methodology [18]:

- Acoustic Survey: Conduct a high-resolution multibeam echosounder (MBES) survey to collect backscatter data, which correlates with seabed sediment composition.

- Ground-Truthing: Collect physical sediment samples (e.g., grab samples) and/or video imagery across the survey area to validate the acoustic data.

- Laboratory Analysis: Measure the grain size and Organic Carbon (OC) content of the ground-truthing samples.

- Spatial Modeling: Establish a strong relationship between acoustic backscatter, sediment type, and OC content. Use this model to predict and map OC distribution across the entire survey area, creating a high-resolution carbon stock map [18].

- Recommended Protocol: A study in Loch Creran, Scotland, successfully used this methodology [18]:

Table 1: Key Methodologies for Addressing Spatial Variation in Marine Sediments

| Method | Primary Application | Key Outputs | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIVERS Variance Decomposition [13] | Quantifying sources of variation in microbial community data. | - Proportion of variance from temporal, spatial, and technical sources.- Identification of noise-dominated taxa. | Requires specific replicate sampling design and spike-in sequences for absolute abundance. |

| VNIR Spectroscopy with Machine Learning [17] | Rapid, high-resolution vertical stratification of sediment profiles. | - Sediment layer classification.- Prediction of chemical parameters (e.g., TC, TN). | Model performance depends on calibration data quality and quantity. |

| Acoustic Seabed Mapping (MBES) [18] | Spatial mapping of sedimentary carbon stocks over large areas. | - High-resolution map of seabed sediment types.- Predictive map of organic carbon distribution. | Requires ground-truthing with physical samples for model calibration. Acoustic signal can be influenced by factors other than sediment type. |

| Community-Level Physiological Profiling (Biolog EcoPlates) [19] | Assessing metabolic potential and carbon source utilization of sediment microbial communities. | - Average Well Color Development (AWCD).- Shannon diversity of carbon source use. | Incubation times can be long (e.g., over 100 days for deep-sea communities). Provides potential function, not in situ activity. |

Table 2: Example Metabolic Diversity Data from Mariana Trench Surface Sediments

This data, obtained using Biolog EcoPlates, shows how microbial metabolic capabilities can vary with depth and location [19].

| Sampling Station | Approx. Depth | Preferential Carbon Source Utilization Order | Shannon Index (H') (Metabolic Diversity) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shallow Stations | < 10,000 m | Polymers > Carbohydrates > Amino Acids > Carboxylic Acids | Significantly lower |

| Deep Stations | > 10,000 m | Polymers > Carbohydrates > Amino Acids > Carboxylic Acids | Significantly higher |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Stratification and Spatial Variation Studies

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Gravity Corer | Collects undisturbed, vertically stratified sediment columns for core analysis [17]. |

| Multibeam Echosounder (MBES) | Provides high-resolution bathymetry and backscatter data for spatial seabed characterization and predicting sediment properties [18]. |

| Visible and Near-Infrared Spectrophotometer | Rapidly collects spectral data from sediment samples, which can be correlated with physical and chemical properties for fast stratification [17]. |

| Biolog EcoPlate | Microplate containing 31 different carbon sources to profile the metabolic capabilities and functional diversity of microbial communities from environmental samples [19]. |

| Spike-in Sequences | Known quantities of foreign DNA or cells added to a sample to allow for the calculation of absolute microbial abundances in sequencing studies, critical for variance decomposition [13]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | A machine learning algorithm used to build classification models, for example, to classify sediment layers based on spectral data [17]. |

| 3,4-Dihydroxydodecanoyl-CoA | 3,4-Dihydroxydodecanoyl-CoA, MF:C33H58N7O19P3S, MW:981.8 g/mol |

| Alexa Fluor 680 NHS ester | Alexa Fluor 680 NHS ester, MF:C39H47BrN4O13S3, MW:955.9 g/mol |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: DIVERS Variance Decomposition Workflow

Diagram 2: VNIR-ML Sediment Stratification

Linking Spatial Patterns to Microbial Metabolism and Function

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers address common challenges in experiments that investigate the link between spatial patterns and microbial metabolism.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My microbial metabolite imaging results lack sufficient spatial detail. What are the key technical factors to improve resolution?

The spatial resolution of your imaging is primarily determined by your sampling protocol and technology choice. For microbial communities, where interactions occur at the micron scale, you require techniques with pixel sizes that match individual cells [20].

- Primary Issue: Using imaging with pixel sizes larger than 10µm will obscure critical details of microbial heterogeneity and metabolic gradients [20].

- Recommended Solution: Employ Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MALDI-MSI), which currently offers the best combination of spatial and molecular resolution for metabolites. While standard systems achieve 5-10µm resolution, prototype systems can reach 1µm, which is necessary for single-cell level detail [20].

- Troubleshooting Tip: If using MALDI-MSI, focus on optimizing matrix chemistry and sample preparation, as these significantly impact detection capability for poorly ionizing metabolites like carbohydrates [20].

Q2: When is environmental sampling for microorganisms scientifically justified, and how can I avoid unnecessary culturing?

According to established guidelines, microbiologic environmental sampling is an expensive and time-consuming process that is only indicated for four specific situations [21]. You should only proceed if your study meets one of these criteria:

| Indication | Protocol Requirements | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Outbreak Investigation | Sampling supported by epidemiological data; molecular epidemiology to link environmental and clinical isolates [21]. | Confirmation of environmental reservoirs or fomites in disease transmission. |

| Research | Use of well-designed and controlled experimental methods [21]. | New information on the spread of healthcare-associated diseases. |

| Hazard Monitoring | Protocol to confirm presence and validate successful abatement of a hazardous chemical/biological agent [21]. | Documentation of hazardous condition and its resolution. |

| Quality Assurance | Protocol to evaluate a change in infection-control practice or equipment performance; use of controls [21]. | Evidence that a change in practice or system performs to specification. |

Q3: How can I directly link microbial identity to metabolic function in a complex host tissue sample?

A powerful approach is the combination of Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI) with 16S rRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) on the same tissue section [20].

- The Challenge: It is difficult to determine which microbes are producing which metabolites in a complex, multi-species environment [20].

- The Solution: FISH uses fluorescently labeled, taxon-specific oligonucleotide probes to identify and localize bacterial cells within tissue sections. When combined with MALDI-MSI on the same section, it directly links microbial identity to the spatial distribution of metabolic activity [20].

- Advanced Application: This integrated protocol can be further complemented with H&E staining to assess host histological phenotypes linked to the presence of specific bacteria or metabolites [20].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing a Spatial Sampling Strategy for Microbial Community Dynamics

This protocol is designed to capture the spatial and temporal variations in microbial communities, as exemplified in studies of aquatic systems like the Bohai Sea [1].

1. Experimental Design:

- Site Selection: Choose sampling sites that represent the ecological gradient of interest (e.g., along a pollution or salinity gradient). For example, a study may use 6 coastal stations near a port and tourist city [1].

- Sample Types: Collect paired samples of surface water (e.g., 3L) and bottom sediment (e.g., 1kg) using a hydrophore and a box corer, respectively [1].

- Temporal Replication: Plan sampling campaigns across different seasons or time points (e.g., June and August) to account for temporal dynamics [1].

2. Field Sampling & Physicochemical Analysis:

- In-situ Measurements: Immediately upon collection, measure temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), and salinity using a calibrated multiparameter instrument [1].

- Lab-based Analysis: Analyze samples for nutrients (PO₄³â», TN, NHâ‚„âº, NOâ‚‚â», NO₃â») and carbon content (DOC, DIC) following standardized oceanographic survey methods [1].

3. Microbiome Analysis Workflow:

- DNA Extraction: Extract metagenomic DNA from water filters (0.22µm) and sediment samples using a validated method like the CTAB protocol [1].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Amplify the 16S rRNA V4 region with specific primers (515F/806R). Construct libraries using a kit like Illumina's TruSeq DNA PCR-Free and sequence on a platform such as Illumina HiSeq2500 [1].

- Bioinformatic Processing: Process sequences to remove chimeras, cluster into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) at ≥97% similarity, and annotate taxonomy using a database like GreenGene [1].

The diagram below illustrates the core workflow for this spatial sampling study.

Spatial Microbial Ecology Workflow

Protocol 2: Integrating Spatial Metabolomics with Microbial Identification

This protocol uses MSI and FISH to connect chemistry with biology in host-associated microbial communities [20].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Tissue Sectioning: Prepare thin, cryopreserved sections of the native host tissue containing the microbial community.

- Metabolite Preservation: Ensure sample processing avoids metabolite degradation or relocation.

2. Sequential Staining and Imaging:

- 16S rRNA FISH: First, apply fluorescently labeled, taxon-specific oligonucleotide probes to the tissue section to identify and localize bacterial cells.

- MALDI-MSI: On the same tissue section, perform MALDI-MSI to visualize the spatial distribution of metabolites, including lipids, peptides, amino acids, and secondary metabolites [20].

3. Data Integration and Analysis:

- Image Co-registration: Overlay the FISH and MSI images to align microbial cell locations with metabolite distributions.

- Correlation Analysis: Statistically identify metabolites that are spatially correlated with specific microbial taxa.

- Functional Inference: Infer metabolic interactions, such as the production of antibiotics or siderophores at inter-colony interfaces [20].

The logical relationship of this integrated approach is shown below.

Spatial Metabolomics Integration Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for the protocols described above.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Taxon-Specific FISH Probes [20] | Targets 16S rRNA to visually identify and localize specific microbial taxa within a tissue sample. | Probes can range from phylum to species specificity. Design depends on study objectives. |

| MALDI Matrix [20] | Enables soft ionization of metabolites for detection by Mass Spectrometry Imaging. | Matrix choice is critical; optimization is required for different metabolite classes (e.g., lipids vs. carbs). |

| TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Kit [1] | Prepares high-quality sequencing libraries for metagenomic analysis without amplification bias. | Ideal for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing to characterize microbial community composition. |

| Illumina HiSeq2500 Platform [1] | Performs high-throughput sequencing of prepared DNA libraries. | Generates 250 bp paired-end reads, suitable for robust OTU clustering and taxonomy assignment. |

| GreenGene Database [1] | A reference database for annotating the taxonomy of 16S rRNA sequences. | Used with an RDP classifier to assign identity to OTUs derived from sequencing. |

| 8-Amino-7-oxononanoic acid hydrochloride | 8-Amino-7-oxononanoic acid hydrochloride, MF:C9H18ClNO3, MW:223.70 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Methyl-2-quinoxalinecarboxylic acid-d4 | 3-Methyl-2-quinoxalinecarboxylic acid-d4, MF:C10H8N2O2, MW:192.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The table below consolidates critical quantitative specifications from the search results to aid in experimental planning and troubleshooting.

| Parameter | Relevant Technique / Context | Quantitative Specification / Finding | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution [20] | Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI) | Standard: 5-10 µm. Advanced/Prototype: 1 µm. | Resolution below 10µm is required to resolve metabolite distributions in microbial colonies. |

| Biomass & Diversity [22] | Slow Sand Filter (SSF) Microbial Communities | Schmutzdecke (top layer) has higher biomass and diversity than deeper sand layers. | Different microbial processes (e.g., organic matter degradation, nitrification) occur at different depths. |

| Archaea Abundance [22] | Slow Sand Filter (SSF) Microbial Communities | Relative abundance of archaea increases with sand depth. | Archaea are adapted to lower-nutrient conditions in deeper filter layers. |

| Community Resilience [22] | Slow Sand Filter (SSF) Scraping Disturbance | Prokaryotic community shows minimal biomass increase for first ~3.6 years post-scraping before maturing. | Biology in engineered systems is resilient; a core community ensures reliable performance after disturbance. |

| Particle Size & Health Risk [21] | Air Sampling for Bioaerosols | Particles ≤5 µm reach the lung; greatest alveolar retention is for 1–2 µm particles. | In outbreak investigations, particle size determination is crucial for linking aerosols to respiratory infections. |

Bridging Theory and Practice: Sampling Designs and Protocols to Control for Spatial Bias

Principles of 3D Spatial Sampling (X, Y, Z-Axes)

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most critical factor for successful 3D spatial sampling? Tissue quality is paramount. The preservation method, RNA integrity, and proper embedding directly determine the quantity and quality of the data you can recover. Even the best sampling design will fail with degraded samples [23].

How do I choose the right spatial resolution for my experiment? The choice involves a trade-off. High resolution (smaller spot size) is essential for studying single-cell or subcellular structures but requires more sections and deeper sequencing to cover the same tissue volume. Lower resolution can be sufficient for understanding tissue-level architecture and is more efficient for larger areas [23].

My sample has low RNA quality (RIN <7). Can I still proceed? Yes, but with managed expectations. While an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) >7 is ideal, biologically meaningful data can still be obtained from samples with lower RIN values (e.g., 6.3), as demonstrated in studies of human metastatic lymph nodes [24].

How can I avoid shadows or missing data in my 3D reconstruction? For 3D surface mapping in profilometry, coaxial measurement systems (where projection and imaging axes are aligned) can overcome the occlusion issues common in traditional triangulation-based systems, enabling the complete reconstruction of complex geometries like deep holes [25].

What is the biggest mistake in designing a 3D spatial experiment? Underpowering the study. A robust experiment requires multiple biological replicates and multiple regions of interest (ROIs) per sample to account for both biological variability and technical noise introduced by tissue heterogeneity and sectioning [23].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 1: Common 3D Spatial Sampling Issues and Solutions

| Issue | Possible Cause | Best Practice Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Long data generation times & high latency [26] | Generating collision/data for complex meshes consumes excessive CPU. | Use the minimum data resolution your application requires. Prioritize data requests and process them one at a time to minimize system slowdown [26]. |

| Excessive geometry/data slowing performance [26] | Too many triangles or data points per unit volume (over-sampling). | Use the minimum resolution of spatial mapping data required. Test your application to find the optimal balance between accuracy and performance [26]. |

| Failed 3D surface reconstruction | Traditional triangulation methods fail on surfaces with steep variations, causing occlusions [25]. | Implement a coaxial measurement system where the projection and imaging axes are aligned. This "what you see is what you measure" principle prevents shadows in deep holes or grooves [25]. |

| High variation between technical replicates | Inconsistent sample handling, permeabilization, or sectioning. | Standardize pre-analytical steps. Perform a pilot experiment to optimize permeabilization conditions (e.g., pepsin concentration and time) for your specific tissue type [24]. |

| Insufficient gene detection | Sequencing depth is too low, especially for FFPE samples or complex tissues. | Sequence deeper than manufacturer minimums. For FFPE tissues, aim for 100,000–120,000 reads per spot instead of the standard 25,000–50,000 to recover sufficient transcripts [23]. |

Table 2: Permeabilization Conditions for Different Tissue Types

The following table, derived from the Open-ST protocol, provides a starting point for optimizing permeabilization, a critical step for efficient mRNA capture [24].

| Species | Tissue Type | Pepsin Timing (min) | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | Brain (E13) | 30 | -- |

| Mouse | Brain (Adult) | 30 | -- |

| Human | Metastatic lymph node | 45 | 1.4 U/μL pepsin |

| Human | Healthy lymph node | 45 | 1.4 U/μL pepsin |

| Human | Head & neck squamous cell carcinoma | 45 | 1.4 U/μL pepsin |

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Robust 3D Spatial Sampling

The diagram below outlines a generalized experimental workflow for 3D spatial transcriptomics, integrating best practices for controlling spatial variation.

Workflow for 3D Spatial Transcriptomics

Computational Data Processing Workflow

After data generation, a robust computational pipeline is essential for transforming raw data into a 3D molecular map.

Computational Pipeline for 3D Data

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for 3D Spatial Transcriptomics

| Item | Function | Protocol Note |

|---|---|---|

| OCT Compound | Optimal Cutting Temperature medium; a water-soluble embedding matrix for freezing and cryosectioning tissues. | Ensures tissue integrity during freezing and provides support for thin sectioning [24]. |

| Isopentane | A coolant used for rapid freezing of tissue samples. | Cooled by liquid nitrogen or dry ice for flash-freezing, which preserves RNA quality and tissue morphology [24]. |

| Pepsin | An enzyme used for tissue permeabilization in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples. | Digests proteins and unlocks crosslinks, allowing mRNA to be captured. Concentration and timing must be optimized per tissue type [24]. |

| HDMI-32-DraI Library | A spatially barcoded oligonucleotide library. | Pre-coated on repurposed Illumina flow cells to create high-resolution capture areas for mRNA binding [24]. |

| Poly-dT Primers | Primers that bind to the poly-adenylated (poly-A) tail of messenger RNA (mRNA). | The foundation for cDNA synthesis in most spatial transcriptomics protocols; efficiency depends on RNA integrity [24]. |

| Curcumin-diglucoside tetraacetate-d6 | Curcumin-diglucoside tetraacetate-d6, MF:C49H56O24, MW:1035.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-(Dimethylamino)acetanilide-d6 | 2-(Dimethylamino)acetanilide-d6, MF:C10H14N2O, MW:184.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

High-Resolution Sampling Strategies for Complex Gradients

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary causes of invalid spatial references in geospatial data for microbial ecology? Invalid spatial references often occur when data is imported from non-ArcGIS systems, or due to the misuse of geoprocessing environments for XY Resolution and XY Tolerance. Manually adjusting these values away from their defaults to save disk space or generalize data can lead to incorrect analytical results, performance issues, or software crashes [27].

Q2: How can I correct an invalid spatial reference in my sampling location data? To correct an invalid spatial reference, you must create a new feature class. Import the original feature class's schema and coordinate system, but use the wizard's "Reset To Default" button on the Tolerance tab and accept the default resolution. After loading your original data into this new feature class, run the Check Geometry and Repair Geometry tools to fix any underlying issues revealed by the correct spatial properties [27].

Q3: Why is the metabolic diversity of microbial communities significantly different between shallow and deep stations in the Mariana Trench? Spatial variation in microbial community structure, driven by environmental factors like sampling depth and total organic carbon (TOC) content, leads to differentiated ecological niches. Furthermore, incubation experiments show that microbial communities at most shallow stations have significantly lower metabolic diversity than those at deep stations, reflecting an initial preference for different carbon sources like polymers and carbohydrates [19].

Q4: What methodology is used to directly link microbial community structure to carbon source utilization potential? A polyphasic approach combining high-throughput 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing with community-level physiological profiling using Biolog EcoPlate microplates is effective. Sequencing reveals taxonomic diversity, while the microplates, incubated for an extended period (e.g., 109 days), measure the utilization of 31 different carbon substrates, thus linking structure to function [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Microbial Community Analysis Due to Spatial Variation

Description Spatial variation in environmental factors like depth and nutrient content can lead to significantly different microbial community structures and metabolic functions, potentially skewing research conclusions if not controlled [19] [1].

Investigation & Resolution

- Root Cause Analysis: Spatial variation is a fundamental driver of microbial community composition. In the Mariana Trench, sampling depth and total organic carbon (TOC) content were key environmental drivers, leading to distinct communities above and below 10,000 meters [19].

- Resolution Strategy: A controlled sampling design that accounts for major environmental gradients is essential.

- Stratified Sampling: Design your sampling strategy to explicitly test the impact of specific gradients (e.g., depth, TOC, distance from shore). Group sampling stations into strata (e.g., shallow vs. deep) for robust comparison [19] [1].

- Environmental Data Collection: Consistently measure and record key physicochemical parameters (e.g., depth, TOC, TN, TP, DO, pH, temperature) at each sampling site to use as co-variables in your analysis [19] [1].

- Standardized DNA Extraction: Use standardized kits, such as the PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit, and consistent procedures across all samples to avoid introducing technical bias [19].

Problem: Sampling Fails to Capture Temporal-Spatial Microbial Dynamics

Description Microbial communities in environments like the Bohai Sea show significant temporal variation (e.g., between June and August), which can interact with spatial variation. Ignoring this can lead to an incomplete or inaccurate understanding of microbial dynamics [1].

Investigation & Resolution

- Root Cause Analysis: Temporal changes (e.g., in temperature, dissolved oxygen, nutrient concentrations) can cause profound shifts in microbial community structure and function, sometimes having a stronger influence than spatial variation [1].

- Resolution Strategy: Integrate temporal scale into sampling design.

- Time-Series Sampling: Conduct sampling at the same locations across multiple time points (e.g., different seasons) to disentangle temporal and spatial effects [1].

- Monitor Environmental Fluctuations: Track parameters like dissolved oxygen, nutrient concentrations (TN, NO₃â», PO₄³â»), and temperature over time, as these are key factors driving temporal changes [1].

- Bioinformatic Adjustment: Use statistical models like Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) and Least Discriminant Analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) to identify which taxa are significantly associated with specific temporal or spatial zones [1].

Experimental Protocols for Microbial Community Analysis

Protocol 1: Assessing Community-Level Metabolic Diversity using Biolog EcoPlates

This protocol measures the functional metabolic diversity of environmental microbial communities based on their carbon source utilization patterns [19].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Suspend 10 g of sediment in 20 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Mix and centrifuge to collect microbial cells, washing twice with buffer to remove soluble carbon. Adjust the final suspension to an optical density between 0.25–0.35 at 420 nm [19].

- Inoculation and Incubation: Add 150 µL of the adjusted suspension to each well of a Biolog EcoPlate. Incubate the plates in the dark at a temperature relevant to the study environment (e.g., 4°C for deep-sea studies) [19].

- Data Acquisition: Measure the absorbance of each well at 590 nm and 750 nm every 24 hours. The 750 nm measurement corrects for turbidity. Incubation may need to be extended for slow-growing communities (e.g., 109 days for deep-sea sediments) [19].

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the Average Well Color Development (AWCD) for the plate or substrate categories:

AWCD = Σ(R - C)/n, whereRis the absorbance of a sample well,Cis the absorbance of the control well, andnis the number of substrates [19]. - Calculate the Shannon diversity index (H') for carbon source utilization:

H' = -Σpi ln(pi), wherepiis the ratio of the relative absorbance of a single well to the sum of all wells [19].

- Calculate the Average Well Color Development (AWCD) for the plate or substrate categories:

Table 1: Carbon Source Categories in a Biolog EcoPlate

| Category | Number of Substrates | Example Substrates |

|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | Multiple | Glycogen, D-Cellobiose |

| Polymers | Multiple | Tween 40, Tween 80 |

| Carboxylic & Acetic Acids | Multiple | D-Glucosaminic Acid, α-Ketobutyric Acid |

| Amino Acids | Multiple | L-Arginine, L-Serine |

| Amines & Amides | Multiple | Phenylethyl-amine |

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Sequencing of Microbial Community Structure

This protocol details the steps for using 16S rRNA gene sequencing to profile the taxonomic composition of microbial communities from sediment samples [19] [1].

Methodology:

- DNA Extraction: Extract metagenomic DNA from sediment samples (e.g., 0.5 g) using a standardized kit like the PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit. Assess DNA concentration and quality via gel electrophoresis and a spectrophotometer [19].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the hypervariable V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene using universal prokaryotic primers (e.g., 515F:

5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′and 806R:5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). Use barcoded primers for multiplexing samples [19] [1]. - Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries using a kit such as the TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation Kit. Sequence the libraries on an Illumina platform (e.g., HiSeq2500) to generate paired-end reads [19] [1].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process sequences to remove chimeras and low-quality reads.

- Cluster high-quality sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity threshold.

- Annotate taxonomic information using a reference database like the GreenGene Database [1].

Table 2: Key Physicochemical Parameters to Measure in Sediment Samples

| Parameter | Standard Measurement Method |

|---|---|

| Total Organic Carbon (TOC) | Elemental analyzer after acid treatment to remove inorganic carbon [19]. |

| Total Nitrogen (TN) | Elemental analyzer [19]. |

| Total Phosphate (TP) | Molybdate colorimetric method after nitric-perchloric acid digestion [19]. |

| Nitrate (NO₃â») | Colorimetric auto-analyzer [19]. |

| Ammonium (NHâ‚„âº) | Colorimetric auto-analyzer [19]. |

| pH | Portable multiparameter instrument (e.g., YSI Pro Plus) or electrode in slurry [1]. |

| Dissolved Oxygen (DO) | Portable multiparameter instrument [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Microbial Community and Metabolic Analysis

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit | Standardized kit for efficient extraction of high-quality metagenomic DNA from complex environmental samples like soil and sediment, critical for downstream sequencing [19]. |

| Biolog EcoPlate | Microplate containing 31 different carbon substrates to profile the metabolic capabilities and functional diversity of an environmental microbial community at the culture-independent level [19]. |

| Primers 515F/806R | Universal prokaryotic primers targeting the V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene, used for amplicon sequencing to determine taxonomic identity and diversity [1]. |

| TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Kit | Library preparation kit for Illumina sequencing that avoids PCR amplification bias, leading to more accurate representation of community structure in sequencing results [19]. |

| 50 mM Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.0) | An isotonic solution used to create homogenous microbial suspensions from sediment samples for inoculation into Biolog EcoPlates without lysing cells [19]. |

| N-Acetyl-4-aminosalicylic Acid-d3 | N-Acetyl-4-aminosalicylic Acid-d3, MF:C9H9NO4, MW:198.19 g/mol |

Experimental Workflow Diagram

Workflow for Spatial Microbial Ecology

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the difference between a technical replicate and a biological replicate?

- Biological replicates are independent biological samples (e.g., different mice, separate field plots, or distinct microbial communities) that account for the natural biological variation in a system [28] [29].

- Technical replicates are repeated measurements of the same biological sample. They are used to assess the variation inherent to the measurement technology itself [28].

2. How do I determine the optimal number of replicates for my experiment? The optimal number depends on your experimental goals and the sources of variation. Key factors include the variance components (biological and technical) and the desired heritability or accuracy level. The general principle for measurement evaluation studies (Type B experiments) is to use two technical replicates per biological replicate when the total number of measurements is fixed [28]. For more complex experiments, such as multi-location trials, the optimal number of replicates (r) can be calculated using quantitative functions that consider genotypic variance, error variance, and the number of locations [30].

3. My microbial community experiment shows divergent results. What could be wrong? In microbial ecology, even under standardized conditions, small initial differences in community composition can lead to divergent outcomes due to tipping points and alternative compositional states [29]. To troubleshoot:

- Ensure that your sample collection and preservation methods (e.g., cryopreservation) are consistent across all replicates [29].

- Verify that the resource environment (growth medium, temperature) is truly uniform.

- Increase the number of biological replicates to better understand the range of possible community trajectories [29].

4. Why is my experiment failing to replicate published findings? Replication failure is frequently the result of underpowered experiments [31]. This can be due to:

- Inadequate sample size: The experiment is too small to detect a true effect reliably.

- Publication bias: A tendency to only publish studies with significant results.

- Laboratory practices: A lack of randomization and blinding during data collection can introduce bias [31]. Improve replication by using hypothesis-driven experimental design with adequate sample sizes, randomization, and blind data collection techniques [31].

5. What are the key factors to control for spatial variation in environmental sampling? For studies like microbial sampling in reservoirs or sediments, key factors include:

- Depth: Prokaryotic composition can vary significantly with depth [22].

- Temporal variation: Community structure and diversity can show distinct seasonal clustering patterns (e.g., spring/summer vs. autumn/winter) [2].

- Environmental parameters: Dissolved oxygen (DO), sediment pH, phosphorus content, and temperature stratification are often key drivers of microbial community structure and must be measured and accounted for [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or Unreliable Measurement Data

Issue: High variability in data makes it difficult to distinguish true biological signals from noise.

Solution:

- Diagnose the Source of Variance: Implement a variance component analysis to distinguish biological variance ((\sigma{Bio}^2)) from technical variance ((\sigma{Tech}^2)) [28]. The total variance is: (s{Tot}^2 = s{Bio}^2 + s_{Tech}^2) [28].

- Optimize Replicate Allocation: For experiments designed to evaluate measurement reliability (Type B studies), the optimal design is to use two technical replicates for each biological replicate [28].

- Check Experimental Conditions: Ensure that technical replicates are truly identical (same sample, same protocol, same operator, same batch of reagents) to properly assess measurement error.

Problem: Low Heritability in Multi-Location Field Trials

Issue: The ability to accurately select the best-performing varieties (e.g., crops) across different locations is low.

Solution:

- Calculate Required Replicates: Use the formula for heritability on a single-year, multi-location basis ((H{ML})) to determine the number of replicates (*r*) needed to achieve your target accuracy [30]. The formula is:

(H{ML} = \frac{\sigma{G, ML}^2}{\sigma{G, ML}^2 + \frac{\sigma{GL}^2}{l} + \frac{\sigma{\epsilon, ML}^2}{l r}})

Where:

- (\sigma{G, ML}^2) = genotypic variance

- (\sigma{GL}^2) = genotype-by-location interaction variance

- (\sigma_{\epsilon, ML}^2) = error variance

- l = number of locations

- r = number of replicates

- Re-Allocate Resources: If the maximum achievable heritability ((H{MML})) is low, increasing the number of locations (*l*) is more effective than adding more replicates per location [30]. The required number of locations can be estimated as: (l = max(1, 3(\frac{\sigma{GL}^2}{\sigma{G, ML}^2}))) to achieve (H{MML} = 0.75) [30].

Problem: Divergent Outcomes in Microbial Community Studies

Issue: Replicate microbial communities, started from similar inoculums under the same conditions, develop into different compositional states.

Solution:

- Standardize the Archive: Use a cryopreserved archive of the starting natural communities to ensure all replicates are revived from an identical baseline, minimizing initial variation [29].

- Verify Resource Environment: Confirm that the growth medium (e.g., leaf litter-based medium) is sterile and identical in all replicates to standardize the selection pressure [29].

- Analyze Community Classes: Perform unsupervised clustering (e.g., based on Jensen-Shannon distance) on the initial community compositions. Recognize that communities from different initial "classes" may follow different, yet self-consistent, trajectories [29]. This divergence may be a inherent property of the system and not a technical error.

Quantitative Data for Experimental Planning

The tables below summarize key formulas and variance data to help determine the optimal number of replicates for your experiments.

Table 1: Formulas for Calculating Optimal Replication in Different Experimental Frameworks

| Experimental Framework | Heritability Formula | Formula for Optimal Number of Replicates (r) |

|---|---|---|

| Single Trial [30] | (H{ST} = \frac{\sigmaG^2}{\sigmaG^2 + \frac{\sigma\epsilon^2}{r}}) | (r{H=0.75} = max(1, 3(\frac{\sigma\epsilon^2}{\sigma_G^2}))) |

| Multi-Location Trial (Single Year) [30] | (H{ML} = \frac{\sigma{G, ML}^2}{\sigma{G, ML}^2 + \frac{\sigma{GL}^2}{l} + \frac{\sigma_{\epsilon, ML}^2}{l r}}) | (r{H=0.75H{MML}} = max(1, 3(\frac{\sigma{\epsilon, ML}^2}{l \sigma{G, ML}^2}) H_{MML})) |

Table 2: Example Variance Components from a Multi-Location Oat Trial [30] This data illustrates how variance components are used in the formulas above. Values are representative and actual numbers will vary by experiment.

| Variance Component | Symbol | Value (Example) |

|---|---|---|

| Genotypic Variance | (\sigma_{G, ML}^2) | 0.10 |

| Genotype-by-Location Interaction Variance | (\sigma_{GL}^2) | 0.05 |

| Error Variance | (\sigma_{\epsilon, ML}^2) | 0.30 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Variance Component Analysis for Replicate Optimization

This protocol is used to partition total variance into biological and technical components, informing optimal replicate allocation [28].

Experimental Design:

- Collect a set of biological samples (e.g., 10 independent microbial communities).

- For each biological sample, perform multiple technical replicates (e.g., 3 repeated measurements of each community). The recommended starting point is 2 technical replicates [28].

- Randomize the order of all measurements to avoid confounding technical effects with time.

Data Collection:

- Apply the measurement technology (e.g., gene expression microarrays, proteomics, 16S rRNA sequencing) to all samples and replicates according to a standardized protocol.

Statistical Analysis:

- Use a linear mixed model to analyze the data. The model for an observed value (X{ij}) is: (X{ij} = \mu + Bioi + Tech{ij}) where:

- (\mu) is the overall mean.

- (Bioi) is the random effect of the (i)-th biological sample, assumed to be normally distributed: (Bioi \sim N(0, \sigma{Bio}^2)).

- (Tech{ij}) is the random error term for the (j)-th technical replicate of the (i)-th biological sample, assumed to be normally distributed: (Tech{ij} \sim N(0, \sigma{Tech}^2)).

- The model assumes biological and technical error terms are independent [28].

- Extract the estimates of the variance components: (\sigma{Bio}^2) and (\sigma{Tech}^2).

- Use a linear mixed model to analyze the data. The model for an observed value (X{ij}) is: (X{ij} = \mu + Bioi + Tech{ij}) where:

Interpretation and Design:

- The reliability (reproducibility) of the measurement can be defined as the ratio of biological variance to total variance [28].

- If the technical variance constitutes a large proportion of the total variance, increasing the number of technical replicates may improve measurement precision. The optimal allocation for a fixed total number of measurements is two technical replicates per biological sample [28].

Protocol 2: Assessing Reproducibility of Microbial Community Dynamics

This protocol is for evaluating the reproducibility and predictability of complex bacterial community assembly [29].

Community Archive Creation:

- Collect a large number of naturally-occurring bacterial communities from your habitat of interest (e.g., 275 rainwater pools from beech trees).

- Separate the bacterial community from co-occurring biota and the environmental matrix.

- Cryopreserve the entire bacterial community to create a frozen, stable archive for future revival.

Replicate Revival and Growth:

- Independently revive multiple replicates (e.g., 4x) of each cryopreserved community.

- Inoculate each revived community into a standardized, complex resource environment (e.g., sterile beech leaf-based growth medium).

- Grow the communities under identical conditions.

Tracking and Analysis:

- Quantify the taxonomic composition of the starting (cryopreserved) communities and the final communities after growth using high-throughput sequencing (e.g., 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing).

- Analyze Reproducibility: Use analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) to test if the replicate communities are more similar to each other than to communities from different starting points [29].

- Identify Community Classes: Perform unsupervised clustering (e.g., using a Jensen-Shannon distance matrix) on the starting communities to identify distinct composition classes [29]. Track the trajectory of these classes to see if they converge or diverge.

Experimental Workflow and Decision Diagram

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for designing a replicate sampling strategy, from defining goals to implementation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Replicate Sampling in Microbial Ecology

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Cryopreservation Archive | Maintains a stable, reproducible source of complex starting communities for repeated revival and experimentation, ensuring consistency across replicates and over time [29]. |

| Standardized Complex Medium | Provides a uniform, sterile resource environment (e.g., based on natural substrates like leaf litter) to study community dynamics under controlled but ecologically relevant conditions [29]. |

| High-Throughput Sequencer | Enables detailed taxonomic and functional profiling of a large number of community replicates, which is essential for robust statistical analysis of reproducibility and divergence [29]. |

| Variance Component Analysis | A statistical method (often using linear mixed models) that partitions total observed variation into its biological and technical sources, providing the quantitative basis for optimal replicate allocation [28] [30]. |

| Heritability Functions | Quantitative formulas that relate the number of replicates, locations, and variance components to the expected accuracy of the experiment, allowing for cost-effective design [30]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core function of the DIVERS protocol? DIVERS (Decomposition of Variance Using Replicate Sampling) is a mathematical and experimental approach that uses replicate sampling and spike-in sequencing to quantify the contributions of temporal dynamics, spatial sampling variability, and technical noise to the variances and covariances of absolute bacterial abundances in microbial communities [13].

Q2: What are the typical input files required to run the DIVERS analysis?

The core analysis script (DIVERS.R) requires two main inputs [32]:

abundance_matrix: A matrix of absolute abundances for each OTU/species and sample.configure: A configuration file that defines the sample hierarchy, detailing the temporal, spatial, and technical replicate relationships for each sample ID.

Q3: My analysis failed because of a "delimiter error" in the input files. How can I fix this?

The DIVERS documentation explicitly warns users to avoid any delimiter (tab or blackspace) in OTU IDs and sample IDs [32]. Ensure that all identifiers in your abundance_matrix and configure files do not contain tabs or spaces.

Q4: What does the abundance threshold parameter (-t) do, and what value should I use?

The abundance threshold (-t) sets a minimum average abundance for an OTU to be included in the covariance/correlation decomposition analysis. This helps focus on biologically relevant signals and avoid noise from low-abundance taxa. The default is 1e-4 [32]. The original study noted that OTUs below a similar cutoff (~10â»â´ in absolute abundance) were primarily dominated by technical noise [13].

Q5: How do I choose between a 3-level and 2-level variance decomposition?

Use -v 3 when your experimental design allows you to distinguish between temporal, spatial, and technical sources of variance. Use -v 2 when you can only separate biological (a combination of temporal and spatial) and technical variances [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Errors in Configuring the Sample Hierarchy File

Problem: The DIVERS.R script fails to run or produces illogical results due to an incorrectly formatted configuration file.

Solution:

Follow the required format for the configure file exactly. The structure depends on the chosen variance depth (-v).

Table: Configuration File Specifications

| Variance Depth | Purpose | Required Columns & Format | Sample Label Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

-v 3 |

Decompose into Temporal, Spatial, and Technical variance. | Columns: sample, temporal, spatial, technical, variable [32].Format: Tab-delimited, with a header row. |

Exactly one sample labelled X, one Y, and one Z for each temporal index [32]. |

-v 2 |

Decompose into Biological and Technical variance. | Columns: sample, biological, technical, variable [32].Format: Tab-delimited, with a header row. |

Exactly one sample labelled X and one Y for each biological index [32]. |

Example of a valid -v 3 configure file content:

Issue 2: Interpreting Variance Decomposition Results

Problem: A user is unsure how to interpret the output file [output_prefix].variance_decomposition.tsv.

Solution: This file contains the key results for each OTU. The columns and their interpretation are as follows:

Table: Guide to Key Output Columns in variance_decomposition.tsv

| Output Column | Description |

|---|---|

Average_abundance |

The mean absolute abundance of the OTU across all samples. |

Total_variance |

The total observed variance in the OTU's absolute abundance. |

Temporal_variances (or Biological_variances) |

The portion of variance explained by genuine temporal fluctuations (or biological factors in a 2-level model) [32]. |

Spatial_variances |

The portion of variance explained by differences between spatial sampling locations [32]. |

Technical_variances |

The portion of variance attributed to measurement noise from library prep, sequencing, etc. [32]. |

Interpretation Guidance:

- An OTU with high

Temporal_variancesis likely responding to genuine time-dependent factors (e.g., host diet, environmental shifts). - An OTU with high

Spatial_variancesindicates significant spatial heterogeneity within the sampled environment (e.g., patchy distribution in a stool or soil sample) [13]. - If