Benchmarking Operon Prediction Algorithms: A Guide for Genomic Research and Drug Discovery

Accurate operon prediction is fundamental for elucidating transcriptional regulation, metabolic pathways, and functional genomics in prokaryotes.

Benchmarking Operon Prediction Algorithms: A Guide for Genomic Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

Accurate operon prediction is fundamental for elucidating transcriptional regulation, metabolic pathways, and functional genomics in prokaryotes. This article provides a comprehensive, multi-faceted benchmark of contemporary operon prediction algorithms, addressing a critical gap between computational prediction and practical application. We explore the foundational principles that underpin different prediction methods, from sequence-based to machine-learning approaches. A detailed methodological review guides the selection and application of tools, while a troubleshooting section addresses common pitfalls in complex genomic regions. Crucially, we present a rigorous validation and comparative framework, evaluating predictors against experimentally validated operons and gold-standard datasets. Designed for genomics researchers, microbiologists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current capabilities and limitations to empower high-confidence operon annotation in diverse research contexts, from basic science to antibiotic target discovery.

The Building Blocks of Operons: From Classical Genetics to Modern Computational Predictions

The operon model, pioneered by François Jacob and Jacques Monod, fundamentally transformed our understanding of gene regulation in prokaryotes [1]. Their work on the lac operon in Escherichia coli not only revealed the existence of messenger RNA (mRNA) as an intermediary between DNA and protein synthesis but also provided a fundamental mechanistic model for how genes are coordinately regulated in response to environmental stimuli [2] [1]. This foundational principle—that functionally related genes are often clustered together and co-regulated in single transcriptional units—has evolved from a conceptual biological model to a critical target for computational prediction in the genomic era. As we transition from the historical significance of this discovery to its contemporary applications, it becomes clear that accurate operon prediction is now indispensable for modern genomic analysis, enabling researchers to annotate gene function, infer regulatory networks, and identify potential drug targets in pathogenic bacteria [3] [4].

The legacy of Jacob and Monod extends far beyond the biochemistry of bacterial metabolism; it has established a conceptual framework that continues to guide computational approaches in microbial genomics. This review examines the current landscape of operon prediction algorithms, benchmarking their performance, methodologies, and applications in prokaryotic genomics research. By comparing classical approaches with emerging machine learning-based tools, we provide researchers with a comprehensive guide for selecting appropriate prediction methods based on their specific genomic analyses and research objectives.

The Evolution of Operon Prediction Methodologies

Foundational Principles and Classical Approaches

Early computational methods for operon prediction relied heavily on criteria established through empirical biological observation. These approaches primarily utilized five fundamental principles: (1) intergenic distance between adjacent genes, (2) conservation of gene clusters across related species, (3) functional relationships between genes based on annotation, (4) presence of sequence elements like promoters and terminators, and (5) experimental evidence such as transcriptomic data when available [3]. These methods achieved notable success, with some demonstrating prediction accuracies exceeding 90% for model organisms like E. coli [3]. However, their performance varied significantly across bacterial species due to differences in genomic architecture and limited comparative genomic data.

The classical approaches to operon prediction are best exemplified by tools that implement the proximon method, which identifies co-directional gene clusters with short intergenic distances (typically < 600 base pairs) as candidate operons [5]. This method calculates intergenic distance (IGD) using the formula: IGD (G1, G2) = (start(G2) - end(G1)) + 1, where G1 and G2 are adjacent co-directional genes [5]. While this approach benefits from computational simplicity, its major limitation lies in the lack of a universal IGD threshold applicable to all bacterial species, potentially leading to both false positives and false negatives in genomes with atypical gene spacing.

Contemporary Machine Learning Frameworks

The emergence of machine learning has significantly advanced operon prediction, moving beyond single-parameter approaches to integrated multi-feature classification. Tools such as bacLIFE represent this new generation, employing random forest models trained on gene cluster absence/presence matrices to predict not only operon structures but also bacterial lifestyle-associated genes [6]. These methods leverage patterns across thousands of genomes to identify genomic signatures associated with specific functional units, achieving higher accuracy across diverse bacterial taxa by incorporating evolutionary conservation, functional annotation, and genomic context into a unified predictive framework.

Another significant advancement is the development of metagenomic operon predictors such as MetaRon, which addresses the unique challenges of contiguity-disrupted metagenomic assemblies [5]. This pipeline combines co-directionality, intergenic distance, and de novo promoter prediction using Neural Network Promoter Prediction (NNPP) to identify operons in mixed microbial communities without requiring reference genomes or experimental validation [5]. The application of such tools to human gut metagenomics has successfully identified operons associated with type 2 diabetes, demonstrating the translational potential of computational operon prediction in disease research [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Operon Prediction Algorithms and Their Performance Characteristics

| Algorithm | Prediction Methodology | Genomic Application | Reported Accuracy | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Proximon-based | Intergenic distance, co-directionality | Complete microbial genomes | ~90% for E. coli [3] | Computational simplicity, rapid analysis |

| MetaRon | Neural Network Promoter Prediction, IGD, co-directionality | Whole-genome & metagenomic data | 87-97.8% (whole-genome), 88.1% (simulated metagenome) [5] | No experimental data required, handles metagenomic contigs |

| bacLIFE | Random forest machine learning, comparative genomics | Large-scale genomic datasets | High predictability of lifestyle-associated genes [6] | Integrates functional prediction, user-friendly interface |

| AI-Enhanced Approaches | Deep learning, pattern recognition | Diverse microbial communities | Identifies novel antimicrobial peptides [7] | Discovers novel genetic associations, high-dimensional analysis |

Benchmarking Operon Prediction Performance

Experimental Protocols for Algorithm Validation

Robust validation of operon prediction algorithms requires standardized experimental frameworks and benchmarking datasets. The following protocols represent established methodologies for assessing prediction accuracy:

Comparative Genomic Analysis Protocol: This approach evaluates operon prediction performance through comparison with experimentally validated operon databases. Researchers typically utilize reference genomes with well-annotated operons (e.g., E. coli MG1655, Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, and Bacillus subtilis str. 16) as gold standards [5]. The validation process involves: (1) extracting all genes from the reference genome; (2) predicting operons using the target algorithm; (3) comparing predictions with experimentally verified operons; and (4) calculating standard performance metrics including sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy [5]. For example, in one comprehensive benchmarking study, MetaRon achieved 97.8% sensitivity, 94.1% specificity, and 92.4% accuracy when applied to the E. coli MG1655 genome [5].

Metagenomic Simulation Protocol: To evaluate performance on complex microbial communities, researchers create simulated metagenomes by mixing sequences from multiple known genomes (typically 3-5 phylogenetically diverse bacteria) [5]. The operon prediction algorithm is then applied to the mixed dataset, and its predictions are compared to the known operon structures from the constituent genomes. This approach tests the algorithm's ability to handle fragmented assemblies and correctly assign genes to their original transcriptional units despite the absence of complete genomic context [5]. Performance metrics are calculated for each constituent genome and averaged to provide an overall accuracy measure.

Functional Validation Protocol: The most rigorous validation involves experimental testing of computational predictions through site-directed mutagenesis and phenotypic characterization [6]. In this approach, researchers: (1) identify predicted lifestyle-associated genes (pLAGs) using tools like bacLIFE; (2) create knockout mutants for selected pLAGs; (3) assess the phenotypic consequences of gene disruption in relevant assays (e.g., plant pathogenesis models); and (4) confirm the functional relevance of predicted operonic genes [6]. This method was successfully applied to validate six previously unknown lifestyle-associated genes in Burkholderia plantarii and Pseudomonas syringae, demonstrating the translational value of computational predictions [6].

Comparative Performance Analysis

When benchmarking operon prediction algorithms, several key performance metrics must be considered. Sensitivity measures the proportion of true operons correctly identified, while specificity reflects the proportion of non-operonic genes correctly rejected [5]. Accuracy represents the overall correctness of predictions, and generalizability indicates performance across diverse bacterial taxa beyond the training dataset.

Recent evaluations reveal that machine learning-based approaches generally outperform classical methods, particularly for metagenomic data and less-characterized bacterial species. The integration of multiple genomic features (intergenic distance, conservation, functional relatedness) in tools like bacLIFE and MetaRon provides more robust predictions than single-criterion methods [6] [5]. However, classical approaches maintain utility for well-characterized model organisms where optimal intergenic distance thresholds have been empirically determined.

Table 2: Experimental Validation Results for Contemporary Operon Prediction Tools

| Validation Method | Algorithm Tested | Dataset | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Genomic Analysis | MetaRon | E. coli MG1655 | 97.8% sensitivity, 94.1% specificity, 92.4% accuracy [5] | [5] |

| Metagenomic Simulation | MetaRon | Simulated mixture of 3 genomes | 93.7% sensitivity, 75.5% specificity, 88.1% accuracy [5] | [5] |

| Functional Validation | bacLIFE | Burkholderia/Pseudomonas genomes (16,846 genomes) | 6 of 14 predicted LAGs experimentally validated as involved in phytopathogenicity [6] | [6] |

| Lifestyle Prediction | bacLIFE | Burkholderia/Paraburkholderia and Pseudomonas genera | Identified 786 and 377 predicted phytopathogenic LAGs, respectively [6] | [6] |

Research Applications and Workflow Integration

Applications in Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

Operon prediction algorithms have become indispensable tools in modern drug discovery pipelines, particularly for identifying novel antibacterial targets. The integration of these computational methods with multi-omics data accelerates several critical phases of therapeutic development:

Target Identification: Comparative genomic analysis of operon structures across bacterial pathogens enables identification of highly conserved genes within and between species, highlighting attractive targets for broad-spectrum antibiotics [8]. Essential genes organized in operons represent particularly promising candidates, as their disruption may affect multiple cellular functions simultaneously. Bioinformatics approaches can rapidly screen thousands of microbial genomes to identify such targets, significantly reducing the initial discovery timeline [4].

Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Mining: Operon prediction is crucial for identifying biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) that encode secondary metabolites with therapeutic potential [7]. Tools like antiSMASH and BiG-SCAPE integrate operon prediction to discover novel antimicrobial compounds, anticancer agents, and other bioactive molecules [6] [7]. The application of AI-driven approaches has dramatically expanded this capability, with one study identifying approximately 860,000 novel antimicrobial peptides through computational mining of genomic data [7].

Mechanism of Action Elucidation: By delineating functionally related gene clusters, operon prediction helps researchers understand the molecular mechanisms underlying bacterial virulence, antibiotic resistance, and host-pathogen interactions [6]. This information is invaluable for designing targeted therapies that disrupt specific pathogenic processes without affecting beneficial microbiota.

Integrated Workflow for Operon Analysis in Genomic Research

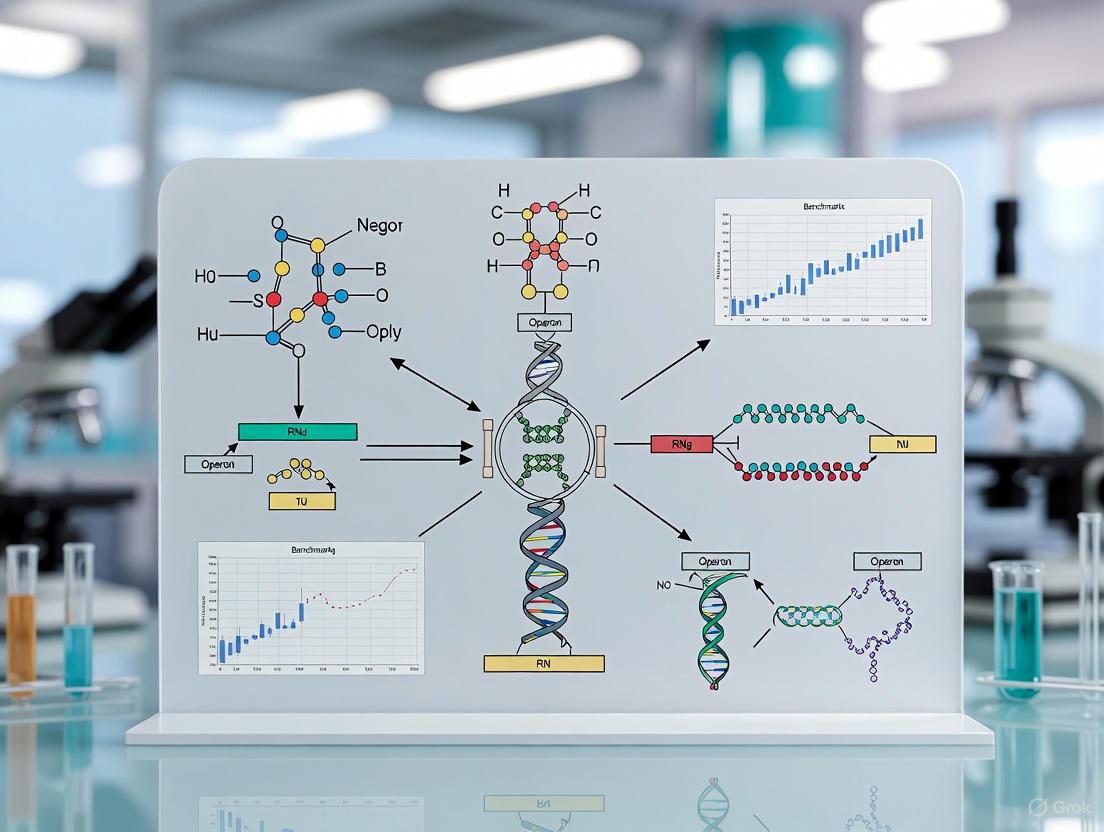

A typical workflow for operon analysis in genomic research incorporates multiple computational tools and validation steps, progressing from data generation through functional interpretation. The following diagram illustrates this integrated process:

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for operon analysis in genomic research, showing the progression from data generation through therapeutic applications.

Successful implementation of operon prediction pipelines requires access to specialized computational tools and biological databases. The following table outlines key resources for researchers in this field:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Operon Analysis

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Databases | Function in Operon Analysis | Access/Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Databases | NCBI RefSeq, GenBank, EMBL, DDBJ [4] | Provide reference genome sequences for comparative analysis | Publicly accessible online |

| Protein Databases | UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot, TrEMBL, UniRef [4] | Functional annotation of predicted operonic genes | Publicly accessible online |

| Pathway Databases | KEGG, BioCyc, ChEMBL [4] | Contextualize operon predictions within metabolic pathways | Publicly accessible online |

| Specialized Tools | MetaRon, bacLIFE, antiSMASH [6] [5] | Operon prediction and biosynthetic gene cluster identification | Open-source with bioinformatics expertise |

| Computational Infrastructure | Python/R programming environments, Snakemake workflow manager [6] | Pipeline implementation and data analysis | High-performance computing recommended |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The field of operon prediction continues to evolve rapidly, driven by advances in artificial intelligence and the exponential growth of genomic data. Future developments will likely focus on several key areas: (1) enhanced prediction accuracy through deep learning models that integrate multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics); (2) improved generalizability across diverse bacterial taxa through transfer learning approaches; and (3) real-time prediction capabilities for clinical and environmental applications [7]. The integration of explainable AI (XAI) principles will be particularly important for building trust in predictive models and generating biologically interpretable results [7].

The legacy of Jacob and Monod's operon model endures not only as a fundamental principle of gene regulation but also as a catalyst for computational innovation in genomics. As we advance toward more sophisticated predictive frameworks, the integration of operon mapping with functional genomics and metabolic modeling will provide increasingly comprehensive understanding of bacterial biology. This progression promises to accelerate drug discovery, enhance metagenomic analysis, and deepen our understanding of microbial ecosystems—a fitting continuation of the revolutionary vision begun by Jacob and Monod over six decades ago.

In prokaryotic genomics, the precise annotation of functional elements is fundamental to understanding gene regulation, cellular function, and ultimately, for applications in synthetic biology and drug development. Promoters, operators, and transcription units represent the core architectural components that orchestrate this regulation. A promoter is a DNA sequence located upstream of a transcription start site (TSS) where RNA polymerase binds to initiate transcription [9] [10]. An operator is a DNA segment, typically situated between the promoter and the genes of an operon, where specific repressor proteins can bind to block transcription [9]. Together, these sequences are integrated into a transcription unit, a segment of DNA transcribed from a single promoter into a single RNA molecule, which may encompass one or more genes [11].

The accurate identification of these components is a central challenge in computational genomics. As high-throughput sequencing technologies advance, the development of robust bioinformatics tools for the de novo annotation of these elements from sequencing data has become a critical area of research. This guide objectively compares the performance and methodologies of various computational models designed to predict these core genomic features, providing a benchmark for researchers in the field.

Core Genomic Components: A Comparative Analysis

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of promoters and operators, which are crucial for the accurate prediction and modeling of transcription units and operons.

| Feature | Promoter | Operator |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A DNA sequence where RNA polymerase binds to initiate transcription [9]. | A DNA segment where repressor molecules bind to an operon [9]. |

| Primary Function | Initiates the transcription of a gene or set of genes [9]. | Regulates gene expression by controlling access to the promoter [9]. |

| Organism Presence | Found in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes [9]. | Found almost exclusively in prokaryotes [9]. |

| Key Sequence Elements (Prokaryotes) | -10 box (Pribnow box) and -35 box [12]. | Short, specific sequence recognized by a repressor protein (e.g., lac operator) [9]. |

| Key Sequence Elements (Eukaryotes) | TATA box, CAAT box, GC box [12]. | Not applicable; transcription factors perform regulatory roles [9]. |

| Regulatory Mechanism | Binding of RNA polymerase, often assisted by transcription factors or sigma factors [9] [10]. | Binding of repressor proteins that physically block RNA polymerase [9]. |

Benchmarking Computational Prediction Models

Experimental methods for identifying promoters and transcription units, such as electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) and DNase footprinting, are well-established but can be time-consuming and costly [13] [14]. Consequently, numerous computational approaches have been developed. The following table compares the performance of several modern methods as reported in recent literature.

| Model Name | Prediction Target | Core Methodology | Reported Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| iPro-CSAF [12] | Promoters (Prokaryotic & Eukaryotic) | Convolutional Spiking Neural Network (CSNN) with spiking attention. | Outperformed methods using parallel CNN layers, capsule networks, LSTM/BiLSTM, and other CNNs on seven species; has low complexity and good generalization [12]. |

| CGAP-HMM [11] | Transcription Units | Multi-task Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) + Hidden Markov Model (HMM). | Showed significant performance improvement in annotation accuracy over existing methods like groHMM and T-units [11]. |

| SVM-based Models [14] | Transcription Factor Binding Sites (TFBS)/Motifs | Support Vector Machine (SVM) using k-mer frequencies. | Can outperform Position Weight Matrices (PWMs), but performance is heavily reliant on training data quality [14]. |

| PWM-based Models [14] | Transcription Factor Binding Sites (TFBS)/Motifs | Position Weight Matrix (PWM) representing nucleotide frequencies. | Robust and interpretable, but assumes positional independence, which can lead to false positives/negatives [14]. |

| Ensemble Voting System [11] | Transcription Units | Combines top three annotation strategies (e.g., CGAP-HMM, groHMM, T-units). | Resulted in large and significant improvements in accuracy over the best individual method [11]. |

Key Experimental Protocols in Prediction Model Development

The development and benchmarking of these computational models rely on standardized experimental protocols:

- Model Training and Validation: Models are typically trained and tested on curated genomic datasets. For example, iPro-CSAF was evaluated on promoter recognition tasks using data from seven species, including E. coli, B. subtilis, and H. sapiens [12]. Similarly, CGAP-HMM was trained on K562 cell line PRO-seq and GRO-seq datasets, with holdout datasets used for final validation to prevent overfitting [11].

- Performance Metrics: Common metrics for evaluating model performance include accuracy, AUC (Area Under the Curve), and equation fidelity. These metrics assess the model's ability to correctly identify functional sites against a background of non-functional sequences [12] [14].

- Handling Data Imbalance: Prediction of binding sites is often an imbalanced learning problem, as the number of non-binding sites vastly exceeds binding sites. Advanced models like the PFDCNN address this by modifying the loss function to correct for bias, thereby improving predictive accuracy on the minority class [15].

The following table details key reagents, datasets, and computational tools essential for research in genomic element annotation and operon prediction.

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| PRO-seq (Precision Run-On and Sequencing) | Measures the production of nascent RNAs to discover active functional elements and transcription units [11]. |

| ChIP-seq (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing) | Genome-wide identification of in vivo transcription factor binding regions (TFBS), considered a gold-standard method [14]. |

| ENCODE Database [14] | A comprehensive collection of ChIP-seq and DNase-seq data from various human tissues and cell lines, used for training and testing prediction models. |

| Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) | A classical biochemical assay to test if a protein binds to a particular DNA sequence by observing a mobility shift in a gel [13]. |

| DNase Footprinting [13] [14] | Identifies the exact sequence to which a protein is bound by detecting the region protected from DNase I digestion. |

| JASPAR / HOCOMOCO [14] | Databases of annotated Position Weight Matrices (PWMs) representing a broad spectrum of known transcription factor binding sites. |

| STREME [14] | An enumerative motif discovery algorithm used to discover overrepresented TFBS motifs in DNA sequences for PWM training. |

Visualizing Transcription Unit Annotation Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the integrated CNN-HMM workflow for annotating transcription units from run-on sequencing data, as implemented in the CGAP-HMM method [11].

Figure 1: Workflow for de novo transcription unit annotation from PRO-seq data.

The benchmarking data presented in this guide demonstrates that while classical models like PWMs remain valuable for their interpretability, modern deep learning and hybrid approaches (e.g., iPro-CSAF, CGAP-HMM) are setting new standards for accuracy in predicting core genomic components. A key trend is the move towards integrated, multi-species models that leverage sophisticated neural architectures to capture complex sequence patterns and dependencies. Furthermore, ensemble methods that combine the strengths of individual predictors show significant promise for achieving the high precision required for sensitive applications in genetic engineering and drug development. As the field progresses, the integration of emerging data types, such as those from improved run-on sequencing assays, and the development of more computationally efficient models will continue to refine our ability to decipher the regulatory code of prokaryotic genomes.

In the realm of prokaryotic genomics, accurate operon prediction represents a critical gateway to understanding bacterial genetics, regulation, and functionality. Operons—clusters of co-transcribed genes sharing a common promoter and terminator—constitute the fundamental transcriptional units that enable bacteria to adaptively respond to environmental stimuli [5]. For researchers and drug development professionals, precisely identifying these structures is paramount for elucidating metabolic pathways, understanding virulence mechanisms, and identifying novel therapeutic targets. Despite decades of computational research and the development of numerous prediction tools, achieving consistent accuracy across diverse bacterial species remains an elusive goal. The fundamental challenge stems from the dynamic nature of operonic organization, which varies considerably across phylogenetic lineages and responds to environmental pressures through evolutionary mechanisms including horizontal gene transfer, mutations, and genetic drift [16]. This article examines the core computational obstacles confronting operon prediction through a systematic benchmarking of contemporary algorithms, analyzing their methodological foundations, performance limitations, and potential pathways toward more robust solutions for genomic research and therapeutic discovery.

Core Computational Obstacles in Operon Prediction

Biological Complexity and Evolutionary Dynamics

The intrinsic biological complexity of bacterial genomes presents the foremost challenge for computational prediction. Operons are not static entities but dynamic structures that evolve through various mechanisms. Prokaryotes demonstrate extraordinary adaptability across diverse ecosystems, largely driven by evolutionary mechanisms such as horizontal gene transfer (HGT), mutations, and genetic drift [16]. These processes continuously introduce novel genetic variations, resulting in significant diversity at both population and species levels. Consequently, operon organization can vary substantially even among closely related strains, complicating the development of universal prediction models. This evolutionary plasticity means that operons conserved in one species may be disrupted or reorganized in another, while new operons continually emerge through genomic rearrangements. This dynamic landscape fundamentally limits the transferability of prediction algorithms trained on model organisms to less-characterized bacterial species, creating a persistent gap in our ability to understand gene regulation in non-model microbes with potential biomedical or biotechnological relevance.

Data Limitations and Annotation Inconsistencies

A second major obstacle concerns the qualitative and quantitative limitations of genomic data. While sequencing technologies have advanced rapidly, producing thousands of bacterial genomes, reliable experimental validation of operon structures has not kept pace. Most algorithms are trained on limited datasets from model organisms like Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, creating inherent biases that reduce performance when applied to underrepresented taxonomic groups [17] [18]. This taxonomic bias reinforces existing gaps in biological understanding and hinders discovery in non-model organisms. Furthermore, metagenomic data presents additional complications due to the cumulative mixture of environmental DNA from millions of cultivable and uncultivable microbes, often without functional information necessary for accurate prediction [5]. The absence of comprehensive, experimentally validated operon databases for diverse bacterial lineages means that computational tools must often rely on indirect evidence rather than confirmed transcriptional units, propagating uncertainties through prediction pipelines.

Benchmarking Operon Prediction Algorithms: Methodologies and Performance

Comparative Framework and Evaluation Metrics

To objectively assess the current state of operon prediction, we established a benchmarking framework focusing on methodological approaches, feature utilization, and performance metrics. We evaluated tools based on their ability to accurately identify both individual operonic gene pairs and complete operon structures with precise boundary detection—the latter being particularly challenging as it requires correctly identifying both start and end points of multi-gene transcriptional units [18]. Our evaluation incorporated standard performance metrics including sensitivity (true positive rate), precision, specificity (true negative rate), F1-score (harmonic mean of precision and sensitivity), accuracy, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) [18]. We particularly emphasized MCC and F1-score as they provide balanced assessments of classifier performance, especially with imbalanced datasets where non-operonic pairs typically outnumber operonic ones.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Operon Prediction Tools on Experimentally Validated E. coli and B. subtilis Operons

| Tool | Sensitivity | Precision | Specificity | F1-Score | Accuracy | MCC | Full Operon Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operon Hunter | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 85% |

| ProOpDB/Operon Mapper | 0.93 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.71 | 62% |

| Door | 0.78 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 61% |

| OperonSEQer | 0.86 | 0.85 | - | 0.85 | - | - | - |

Algorithm Methodologies and Feature Analysis

Contemporary operon prediction algorithms employ diverse computational approaches leveraging different feature sets and methodological frameworks:

Operon Hunter utilizes deep learning and visual representation learning, analyzing images of genomic fragments that capture gene neighborhood conservation, intergenic distance, strand direction, and gene size [18]. This approach mimics how human experts visually identify operons by synthesizing multiple features simultaneously.

OperonSEQer employs machine learning algorithms that use statistical analysis of RNA-seq data, specifically the Kruskal-Wallis test statistic and p-value, to determine if coverage signals across two genes and their intergenic region originate from the same distribution, combined with intergenic distance [19].

Operon Mapper (ProOpDB) relies on an artificial neural network that primarily uses intergenic distance and functional relationships derived from STRING database scores, which incorporate gene neighborhood, fusion, co-occurrence, co-expression, and protein-protein interactions [20] [18].

Door implements a combination of decision-tree-based and logistic function-based classifiers using features including intergenic distance, presence of specific DNA motifs, ratio of gene lengths, functional similarity, and conservation of gene neighborhoods [18].

MetaRon predicts operons from metagenomic data using co-directionality, intergenic distance, and presence/absence of promoters and terminators without requiring experimental or functional information [5].

Unsupervised Methods combine comparative genomic measures with intergenic distances, automatically tailoring predictions to each genome using sequence information alone without training on experimentally characterized transcripts [21].

Table 2: Algorithm Methodologies and Primary Features in Operon Prediction Tools

| Tool | Computational Approach | Primary Features Utilized | Genomic Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operon Hunter | Deep Learning (Visual Representation) | Gene neighborhood conservation, intergenic distance, strand direction, gene size | Whole genomes |

| OperonSEQer | Machine Learning (Statistical + ML) | RNA-seq expression coherence, intergenic distance | Whole genomes with transcriptomic data |

| Operon Mapper | Artificial Neural Network | Intergenic distance, STRING functional relationships | Whole genomes |

| Door | Decision Trees/Logistic Regression | Intergenic distance, DNA motifs, gene length ratio, functional similarity, conservation | Whole genomes |

| MetaRon | Rule-based + Promoter Prediction | Co-directionality, intergenic distance, promoter/terminator presence | Metagenomes and whole genomes |

| Unsupervised Methods | Comparative Genomics + Statistics | Intergenic distance, phylogenetic conservation, functional categories | Any prokaryotic genome |

Experimental Protocols for Algorithm Validation

Rigorous validation of operon prediction tools requires standardized experimental frameworks and benchmarking datasets. Based on published evaluations, the following protocols represent current best practices:

RNA-seq Processing and Analysis Protocol (OperonSEQer)

- Data Collection: Obtain RNA-seq datasets from diverse bacterial species representing both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria with varying GC content [19].

- Read Alignment: Process raw sequencing reads through quality control and align to reference genomes using standard tools like Bowtie2 or BWA.

- Coverage Calculation: Compute read coverage depth for gene bodies and intergenic regions using tools such as bedtools.

- Statistical Testing: Apply Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test to determine if coverage signals from two adjacent genes and their intergenic region derive from the same distribution.

- Feature Integration: Combine the resulting statistic and p-value with intergenic distance measurements.

- Machine Learning: Train classifiers (e.g., Random Forest, SVM, Neural Networks) using these features against validated operon sets.

- Voting System Implementation: Apply threshold-based voting across multiple algorithms to optimize for either high recall or high specificity based on research priorities [19].

Visual Representation Learning Protocol (Operon Hunter)

- Image Generation: Create visual representations of genomic fragments that capture gene neighborhoods, including conservation across related genomes, intergenic distances, strand direction, and gene sizes [18].

- Transfer Learning: Utilize pre-trained neural networks (e.g., ResNet, Inception) and re-train them on limited datasets of experimentally validated operons.

- Data Augmentation: Apply image transformation techniques to expand training datasets and improve model robustness.

- Attention Mapping: Use Grad-CAM methods to generate heatmaps highlighting regions of importance in the visual representations, enabling interpretability of model decisions [18].

- Performance Validation: Evaluate predictions against gold-standard operon databases with precise boundary information.

Metagenomic Operon Prediction Protocol (MetaRon)

- Sequence Processing: Perform de novo assembly of metagenomic reads using IDBA-UD or similar assemblers [5].

- Gene Prediction: Identify open reading frames using Prodigal or MetaGeneMark.

- Proximon Identification: Detect co-directional gene clusters with intergenic distances <600bp using the formula: IGD(G1,G2) = start(G2) - end(G1) + 1 [5].

- Promoter/Terminator Prediction: Apply Neural Network Promoter Prediction (NNPP) and terminator prediction algorithms.

- Operon Delineation: Split proximons into individual operons based on predicted transcriptional boundaries.

Key Technical Hurdles and Limitations

Intergenic Distance Variability

Intergenic distance represents one of the most consistently utilized features in operon prediction, with genes in the same operon typically separated by shorter distances than adjacent genes in different transcriptional units [21] [5]. However, the optimal threshold for distinguishing operonic from non-operonic pairs varies significantly across species. For instance, research has demonstrated that genes in operons are separated by shorter distances in Halobacterium NRC-1 and Helicobacter pylori than in E. coli [21], complicating the transfer of distance-based models between species. While tools like MetaRon employ a flexible threshold (<600bp) to accommodate diverse bacteria [5], this approach increases false positives in genomes with generally compact intergenic regions. The fundamental limitation lies in the overlapping distributions of intergenic distances for operonic versus non-operonic gene pairs, making perfect separation based on distance alone mathematically impossible.

Transcriptional Boundary Detection

Accurately identifying the precise start and end points of operons represents a particularly persistent challenge. Most algorithms initially predict operonic gene pairs, which are subsequently merged into multi-gene operons [18]. This approach frequently leads to boundary errors, where either two separate operons are merged into one or a single operon is split into multiple units. Experimental data reveals that while tools like ProOpDB achieve 93% sensitivity for gene pair prediction, their accuracy drops to just 62% for full operon prediction with correct boundaries [18]. Similarly, Door's performance decreases from 92% precision on gene pairs to 61% on full operons. This precipitous decline in performance at boundary detection highlights the fundamental difficulty in recognizing transcriptional start and termination signals, especially in the absence of high-quality annotation or experimental data for the specific organism being analyzed.

Computational Resource Requirements

As genomic datasets expand to include thousands of strains, computational efficiency becomes increasingly important. Pan-genome analysis tools like PGAP2 have emerged to handle large-scale genomic comparisons, employing strategies such as fine-grained feature analysis within constrained regions to balance accuracy and computational load [16]. Nevertheless, methods that incorporate multiple evidence sources (e.g., phylogenetic conservation, RNA-seq data, functional relationships) typically demand substantial computational resources, creating practical barriers for researchers without access to high-performance computing infrastructure. This challenge is particularly acute for metagenomic operon prediction, where MetaRon must process complex microbial communities without prior functional information [5].

Diagram 1: Operon Prediction Computational Workflow. This diagram illustrates the multi-stage process of operon prediction, from data input through feature analysis, algorithmic processing, and final validation. The workflow demonstrates how different evidence sources feed into various prediction methodologies.

Emerging Solutions and Future Directions

Novel Computational Approaches

Innovative computational strategies are emerging to address persistent challenges in operon prediction:

Biological Language Models: The Diverse Genomic Embedding Benchmark (DGEB) represents a novel approach using protein language models (pLMs) and genomic language models (gLMs) to capture functional relationships between genomic elements, including operonic genes [17]. These models learn from diverse biological sequences across the tree of life, potentially overcoming biases toward model organisms. However, current implementations show limitations—nucleic acid-based models generally underperform protein-based models, and performance for underrepresented groups like Archaea remains poor even with model scaling [17].

Visual Representation Learning: Operon Hunter demonstrates how deep learning applied to visual representations of genomic neighborhoods can capture complex features that challenge quantitative methods [18]. By mimicking how human experts visually identify operons, these approaches can synthesize multiple evidence types simultaneously. The method's attention mapping capability further enhances interpretability by highlighting genomic regions that most influence predictions, allowing expert validation of decision processes [18].

Integrated Pan-genome Analysis: PGAP2 addresses scalability challenges through fine-grained feature analysis within constrained regions, enabling efficient processing of thousands of genomes while maintaining prediction accuracy [16]. By organizing data into gene identity and synteny networks, then applying dual-level regional restriction strategies, the tool reduces computational complexity while improving orthologous gene cluster identification—a critical foundation for comparative operon prediction across bacterial populations.

Research Reagent Solutions for Operon Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Operon Prediction and Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Annotation | NCBI PGAP [22], Prokka | Structural and functional gene annotation | Provides essential gene calls and coordinates for operon prediction |

| Operon Databases | RegulonDB [23], DBTBS [18], BioCyc [17] | Experimentally validated operon references | Benchmarking and training prediction algorithms |

| Functional Databases | STRING [18], COG [21], Gene Ontology | Protein functional relationships | Assessing functional relatedness between adjacent genes |

| Sequence Analysis | BLAST, OrthoMCL, Roary | Homology and orthology detection | Comparative genomics for conservation-based features |

| Motif Discovery | BOBRO [23], NNPP [5] | Regulatory motif identification | Promoter and terminator prediction for boundary detection |

| Expression Analysis | RNA-seq aligners, bedtools, DESeq2 | Transcriptomic data processing | Expression coherence analysis for operon validation |

| Pan-genome Analysis | PGAP2 [16], Panaroo, Roary | Cross-strain gene cluster identification | Evolutionary conservation of gene neighborhoods |

| Benchmarking Platforms | DGEB [17] | Multi-task functional evaluation | Assessing biological language models for operon prediction |

Accurate operon prediction remains a challenging computational problem at the heart of prokaryotic genomics, with significant implications for basic research and therapeutic development. Our benchmarking analysis reveals that while current tools achieve reasonable performance on model organisms with abundant training data, accuracy substantially declines when applied to non-model species or metagenomic samples. The most promising approaches integrate multiple evidence types—intergenic distance, evolutionary conservation, functional relationships, and transcriptomic data—through flexible machine learning frameworks that can adapt to taxonomic diversity. Emerging methodologies, including biological language models and visual representation learning, offer potential pathways toward more robust predictions across the bacterial domain. Nevertheless, fundamental biological complexities and limitations in experimentally validated operon databases continue to constrain performance. Future progress will require coordinated development of computational algorithms, expanded validation datasets spanning diverse bacterial lineages, and standardized benchmarking frameworks that objectively assess both gene-pair predictions and complete operon structures with precise boundaries. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting appropriate prediction tools must consider specific application contexts, taxonomic focus, and available genomic resources—with even state-of-the-art algorithms requiring experimental validation for critical applications.

Operons, fundamental units of transcriptional regulation in prokaryotes, are clusters of genes co-transcribed into a single polycistronic mRNA. Accurate operon prediction is crucial for elucidating gene function, regulatory networks, and metabolic pathways in bacterial genomes. For researchers and drug development professionals, benchmarking the performance of diverse prediction algorithms is essential for selecting appropriate tools for genomic annotation and systems biology modeling. This guide provides a historical perspective and objective comparison of landmark operon prediction algorithms, detailing their underlying principles, evolutionary trajectories, and performance metrics to establish a rigorous benchmarking framework for prokaryotic genomics research.

Historical Evolution of Operon Prediction Algorithms

The development of operon prediction algorithms reflects an evolution from simple heuristic methods to sophisticated integrative approaches leveraging statistical learning and comparative genomics. The table below chronicles this technological progression.

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Landmark Operon Prediction Algorithms

| Decade | Algorithm/Study | Core Principle | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000s | Bergman et al. (2005) [21] | Integrated comparative genomics & intergenic distance | Unsupervised, genome-specific statistical model |

| 2010s | Taboada et al. (2010) [24] | Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | Combined intergenic distance & functional relationship scores |

| 2010s | Operon-mapper (2018) [24] | Web server implementation of ANN | User-friendly access; high accuracy (94.6% in E. coli) |

| 2010s | Janga et al. (2010) [25] | Signature-based prediction | Used sigma-70 promoter-like signal densities |

| 2020s | Regulon Prediction Framework (2016) [23] | Operon-level co-regulation score (CRS) & graph model | Ab initio inference of maximal regulon sets |

Early methods relied heavily on intergenic distance, observing that genes within the same operon are typically separated by fewer base pairs than adjacent genes in different transcription units [21]. The 2005 work by Bergman et al. was significant for creating an unsupervised model that tailored its predictions to each specific genome using sequence information alone, avoiding reliance on pre-existing operon databases [21].

A major shift occurred with the incorporation of functional relationships between gene pairs. The method by Taboada et al., which later powered the Operon-mapper web server, used an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) that took both intergenic distance and a functional score derived from databases like STRING or Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs) as input [24]. This combination significantly improved accuracy, achieving up to 94.6% in E. coli [24]. Subsequent approaches further integrated evolutionary conservation, phylogenetic profiles, and later, motif discovery for regulon elucidation, moving from predicting simple operons to complex, multi-operon regulatory networks [23].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Key Algorithms

Benchmarking against experimentally validated operon sets in model organisms provides critical performance metrics. The following table summarizes the documented accuracy of several key algorithms.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of Operon Prediction Algorithms

| Algorithm | Underlying Principle | Reported Accuracy (E. coli) | Reported Accuracy (B. subtilis) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bergman et al. (2005) [21] | Unsupervised integrated model (distance & comparative genomics) | 85% | 83% | Genome-specific; no training data required |

| Taboada et al. (2010) [24] | Artificial Neural Network (distance & functional score) | 94.6% | 93.3% | High accuracy in model organisms |

| Operon-mapper (2018) [24] | ANN-based web server | 94.4% | 94.1% | High accuracy; ease of use; generates annotation data |

| Janga et al. (Signature-based) [25] | Promoter-like signal density | N/A | N/A | Useful for genomes without comparative data |

The performance data reveals a clear trend of increasing accuracy with the integration of more diverse data types. The simple intergenic distance model, while foundational, is insufficient for high-fidelity predictions across diverse bacterial genomes, as the optimal distance threshold can vary between species [21]. The incorporation of functional relatedness scores, often derived from COG classifications, provided a significant boost [24] [25]. These functional scores quantify the likelihood that two genes participate in the same biological pathway or complex, a strong indicator of co-transcription.

Modern frameworks focus on regulon prediction, which groups operons co-regulated by a common transcription factor. These methods, as described by Song et al., rely on identifying conserved cis-regulatory motifs in promoter regions and using a novel Co-Regulation Score (CRS) to cluster operons into regulons [23]. This represents a more complex challenge but offers a systems-level view of transcriptional regulation.

Experimental Protocols for Algorithm Benchmarking

A standardized experimental protocol is vital for the objective benchmarking of operon prediction algorithms. The following workflow outlines a robust methodology for performance evaluation.

Detailed Methodology

Reference Data Curation: The benchmark relies on a gold-standard dataset of experimentally validated operons. Databases like RegulonDB for E. coli are the primary source [23]. This set is divided into known operon pairs (positive controls) and non-operon pairs (negative controls) for subsequent evaluation.

Genome Sequence and Annotation Preparation: The complete genome sequence in FASTA format is the minimal input. Some algorithms, like Operon-mapper, can accept additional pre-computed annotation files (e.g., GFF or GenBank formats) containing genomic coordinates of Open Reading Frames (ORFs), which can be generated by tools like Prokka [24].

Algorithm Execution: Each algorithm is run on the target genome using its standard parameters and input requirements. This may involve:

- Operon-mapper: Submitting the FASTA sequence to the web server or running the underlying Perl scripts [24].

- Integrated Models: Running custom scripts (e.g., in R or Perl) that calculate intergenic distances, extract COG-based functional scores, and compute conservation metrics across reference genomes [21] [23].

Prediction Validation: The output from each algorithm—a list of predicted gene pairs classified as being in the same operon or not—is compared against the gold-standard dataset. This step identifies true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives.

Performance Metric Calculation: Standard metrics are calculated to quantify performance.

- Accuracy: The proportion of all predictions that are correct (True Positives + True Negatives) / Total Predictions.

- Precision: The proportion of predicted operon pairs that are correct (True Positives) / (True Positives + False Positives).

- Recall (Sensitivity): The proportion of actual operon pairs that are correctly predicted (True Positives) / (True Positives + False Negatives).

Successful operon prediction and benchmarking require a suite of computational tools and data resources. The following table details these essential components.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Operon Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Operon Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Prokka | Software Tool | Rapid annotation of prokaryotic genomes and identification of ORF coordinates [24]. |

| COG Database | Functional Database | Provides orthology groups for assigning functional relatedness scores to gene pairs [24] [25]. |

| STRING Database | Functional Database | Source of protein-protein interaction scores used as a proxy for functional linkage [24]. |

| RegulonDB | Curated Database | Repository of experimentally validated operons and regulons in E. coli, used for training and benchmarking [23]. |

| DOOR2.0 | Operon Database | Database of predicted operons for thousands of bacteria, used for comparative analysis [23]. |

| OrthoMCL | Software Tool | Identifies ortholog groups across multiple genomes for comparative genomics analyses [25]. |

The journey of operon prediction from simple distance-based models to sophisticated, integrative systems like regulon elucidation frameworks demonstrates a consistent drive for higher accuracy and biological relevance. Benchmarking studies consistently show that algorithms combining multiple evidence types—particularly intergenic distance, functional relatedness, and evolutionary conservation—achieve superior performance. For researchers in genomics and drug development, the choice of algorithm depends on the specific organism, the availability of prior experimental data, and the biological question, whether it is simple operon identification or reconstruction of genome-scale regulatory networks. The continuous development of tools and databases ensures that operon prediction remains a dynamic and critical field in prokaryotic genomics.

Intergenic Distance, Conservation, and Co-expression as Foundational Prediction Features

Accurately mapping operons is a critical step in deciphering the regulatory networks of prokaryotic genomes, with direct implications for understanding bacterial pathogenesis and guiding antibiotic discovery [26]. While operons are classically defined as sets of genes co-transcribed into a single polycistronic mRNA, their structures are dynamic and can vary with environmental conditions [27]. Computational prediction of these structures has therefore become an essential tool in genomics. Over years of methodological refinement, three features have emerged as foundational to operon prediction algorithms: intergenic distance, evolutionary conservation, and co-expression data. These features leverage distinct yet complementary biological principles—physical genomics, evolutionary pressure, and transcriptional coordination—to infer which genes are organized into operons. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these core features, detailing their underlying mechanisms, experimental support, and relative performance in the context of benchmarking operon prediction algorithms.

Comparative Analysis of Core Prediction Features

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, mechanisms, and performance metrics of the three foundational features used in operon prediction.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Foundational Operon Prediction Features

| Feature | Biological Principle | Typical Data Sources | Key Strength | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intergenic Distance | Genes within an operon are typically closer to each other than to genes at transcription unit borders [28] [26]. | Genomic sequence annotation. | Simple to compute; highly informative; consistently a top-performing single feature [28]. | Cannot predict complex operon structures or those with unusually large intergenic gaps. |

| Conservation (Gene Order) | Genomic colinearity and gene order within operons can be maintained across evolutionarily related species [26]. | Comparative genomics; multi-species genome alignments. | High specificity; provides evolutionary validation [26]. | Lower sensitivity; operon structure is not always conserved [26]. |

| Co-expression | Genes within an operon are co-transcribed and often show correlated expression profiles across multiple conditions [27] [29]. | Microarray data; RNA-seq transcriptome profiles. | Can reveal condition-dependent operon structures [27]. | Co-expression can occur for non-operonic genes (e.g., coregulated regulons); dependent on data quality and breadth [30]. |

The quantitative performance of these features when integrated into computational models is demonstrated in the following table, which summarizes results from key studies.

Table 2: Reported Performance of Integrated Prediction Methods

| Study / Method | Genome Tested | Integrated Features | Reported Accuracy | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-approaches-guided GA [29] | E. coli K12 | Intergenic distance, COG, Metabolic pathway, Microarray expression | 85.99% | Using different methods to preprocess different genomic features improves performance. |

| Multi-approaches-guided GA [29] | B. subtilis | Intergenic distance, COG, Metabolic pathway, Microarray expression | 88.30% | Demonstrated the method's applicability beyond model organisms. |

| Multi-approaches-guided GA [29] | P. aeruginosa PAO1 | Intergenic distance, COG, Metabolic pathway, Microarray expression | 81.24% | Highlights challenge of predicting operons in less-characterized genomes. |

| Consensus Approach [26] | S. aureus Mu50 | Gene orientation, Intergenic distance, Conserved gene clusters, Terminator detection | 91-92% | Successfully predicted operons in a genome with limited experimental data. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Quantifying the Intergenic Distance Effect on Co-expression

Objective: To systematically assess the contribution of genomic distance to the coexpression of coregulated genes, independent of their shared regulation [30] [31].

Methodology Overview:

- Data Curation: Curated transcriptional regulatory interactions and operon information were obtained from RegulonDB for E. coli K-12. A large-scale gene expression compendium (4,077 condition contrasts) was used to compute coexpression [30] [31].

- Gene Pair Selection: Pairs of coregulated genes (sharing at least one transcription factor with the same regulatory role) were identified. To isolate the distance effect from operonic confounding, gene pairs within the same operon were excluded from the analysis [30].

- Coexpression Measurement: The pairwise similarity of gene expression profiles was calculated using the Spearman Correlation Rank (SCR). A lower SCR indicates a higher degree of coexpression [30] [31].

- Distance Analysis: The genomic distance was defined as the number of base pairs between the start positions of two genes. The mean degree of coexpression (median SCR) was analyzed as a function of the genomic distance between gene pairs [30].

Key Result: The study found an inverse correlation between genomic distance and coexpression. Coregulated genes exhibited higher degrees of coexpression when they were more closely located on the genome, even after excluding operonic pairs. This distance effect was sufficient to guarantee coexpression for genes at very short distances, irrespective of the tightness of their coregulation [30].

Predicting Condition-Dependent Operons with Integrated Data

Objective: To generate accurate, condition-specific operon maps by integrating static genomic features with dynamic transcriptomic data [27].

Methodology Overview:

- Data Integration: The method combines RNA-seq-based transcriptome profiles from a specific condition with static DNA sequence features (e.g., intergenic distance) [27].

- Feature Extraction:

- Transcript Boundaries: A sliding window algorithm identifies transcription start and end points (TSPs/TEPs) from RNA-seq coverage depth.

- Expression Levels: Expression values for coding sequences (CDS) and intergenic regions (IGR) are calculated using RPKM.

- Operon Confirmation: A set of confirmed operon pairs (OPs) and non-operon pairs (NOPs) is established by linking TSPs/TEPs to known operon structures from databases like DOOR [27].

- Model Training and Prediction: Classifiers (Random Forest, Neural Network, Support Vector Machine) are trained on the confirmed OPs and NOPs using both genomic and transcriptomic features. The trained models are then used to classify unlabeled gene pairs and construct a condition-dependent operon map [27].

Key Result: The integration of DNA sequence and RNA-seq expression data resulted in more accurate operon predictions than either data type alone, successfully capturing the dynamic nature of operon structures [27].

Logical and Pathway Visualizations

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and integration points of the three core features in a state-of-the-art operon prediction workflow.

Figure 1: Logic Flow of an Integrated Operon Prediction Pipeline. The workflow shows how raw data sources are processed into distinct features, which are then combined in a computational model to generate a final operon prediction map.

Successful operon prediction and benchmarking rely on a suite of public databases and software tools. The table below lists key resources for data, model training, and validation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Operon Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Operon Prediction | Relevant Feature(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RegulonDB [30] [31] | Database | A curated repository of transcriptional regulation and operon information for E. coli K-12, used as a gold standard for training and validation. | All |

| DOOR [27] | Database | A database of operons for multiple prokaryotic genomes, useful for obtaining confirmed operon sets for model training. | All |

| COLOMBOS [31] | Database | A large-scale expression compendium for prokaryotes, providing cross-condition gene expression data for coexpression analysis. | Co-expression |

| NCBI GenBank [29] [26] | Database | The primary repository for publicly available nucleotide sequences, used to obtain genomic data for analysis. | Intergenic distance, Conservation |

| Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) [29] [28] | Database | A phylogenetic classification of proteins from multiple genomes, used to assess functional relatedness of adjacent genes. | Conservation |

| GGRN/PEREGGRN [32] | Software Engine | A modular benchmarking platform for evaluating gene regulatory network models and expression forecasting methods. | Co-expression, Validation |

| Multi-approaches-guided Genetic Algorithm [29] | Software/Method | An example of an advanced computational method that integrates multiple data types using specialized preprocessing for each feature. | All (Integration) |

The benchmarking of operon prediction algorithms consistently demonstrates that integration of multiple features—primarily intergenic distance, conservation, and co-expression—yields superior results compared to reliance on any single feature [29] [28]. Intergenic distance remains a powerful and simple predictor, while conservation provides high-specificity evolutionary context. Co-expression data from high-throughput transcriptomics is indispensable for capturing the condition-dependent dynamics of operon structures [27].

Future advancements in the field will be driven by several factors: the growing availability of high-quality RNA-seq data across diverse conditions, the development of more sophisticated machine learning models that can effectively leverage these large datasets [32], and the refinement of comparative genomics approaches to trace regulatory element orthology even in the absence of direct sequence conservation [33]. As these resources and methods mature, the accuracy and applicability of operon prediction across a wide range of prokaryotic organisms will continue to improve, deepening our understanding of bacterial gene regulation and opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

A Practical Toolkit: Selecting and Applying Modern Operon Prediction Algorithms

Operons, sets of contiguous genes co-transcribed into a single polycistronic mRNA, represent a fundamental principle of transcriptional organization in prokaryotes. Accurate operon prediction is crucial for understanding bacterial gene regulation, functional annotation, and metabolic pathway reconstruction. As the number of sequenced bacterial genomes continues to grow, computational methods for operon identification have evolved from early sequence-based approaches to sophisticated comparative genomics and machine learning algorithms. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these methodological paradigms, evaluating their performance, data requirements, and applicability across diverse prokaryotic genomes to inform selection for research and drug development applications.

Methodological Paradigms in Operon Prediction

Sequence-Based and Conservation-Driven Approaches

Early computational approaches to operon prediction relied heavily on features intrinsic to genomic sequence and organization, requiring no experimental data beyond the genome sequence itself.

- Intergenic Distance Analysis: Multiple studies have consistently demonstrated that shorter intergenic distances between genes strongly correlate with operon membership. This feature remains one of the most universal and portable predictors across bacterial species [34].

- Conservation of Gene Order: Comparative analyses examine whether the sequential order of gene pairs is conserved across multiple phylogenetically related genomes. This method offers high specificity (approximately 98%) but suffers from limited sensitivity as it primarily identifies conserved core operons while missing organism-specific arrangements [35] [34].

- Integrated Statistical Models: Advanced implementations combine multiple sequence-based features within unified statistical frameworks. One prominent approach utilizes a Bayesian hidden Markov model (HMM) that integrates intergenic distance with phylogenetic distribution data, achieving >85% specificity and sensitivity in Escherichia coli K12 [34].

A significant limitation of pure conservation-based methods is their inherent insensitivity to operons containing unique or poorly conserved genes, typically allowing coverage of only 30-50% of a given genome [34].

Machine Learning and RNA-seq Driven Approaches

The advent of high-throughput transcriptomics has enabled a new generation of operon prediction tools that leverage gene expression data alongside machine learning algorithms.

- OperonSEQer: This framework employs a non-parametric statistical analysis (Kruskal-Wallis test) of RNA-seq coverage across adjacent genes and their intergenic region to determine if the signals originate from the same distribution. It incorporates six machine learning algorithms with a voting system that allows users to prioritize either high recall or high specificity based on their research needs [19].

- Rockhopper: This system utilizes a unified probabilistic model that combines primary genomic sequence information with RNA-seq expression data to identify operons throughout bacterial genomes [36].

- OpDetect: Representing the current state-of-the-art, this method uses a convolutional and recurrent neural network architecture that processes RNA-seq reads as signals across nucleotide bases. This approach directly leverages nucleotide-level expression patterns without extensive feature engineering, demonstrating superior performance in recall, F1-score, and AUROC compared to previous methods [37].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Operon Prediction Methodologies

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Primary Data Sources | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Based & Comparative Genomics | Bayesian HMM [34], Conservation-based [35] | Genomic sequence, Intergenic distance, Phylogenetic conservation | High portability to newly sequenced genomes, No requirement for experimental data | Lower sensitivity for unique genes, Limited to ~50% genome coverage |

| Machine Learning with RNA-seq | OperonSEQer [19], Rockhopper [36] | RNA-seq data, Intergenic distance, Statistical features | Condition-specific predictions, Higher accuracy for studied organisms | Requires RNA-seq data, Performance depends on data quality |

| Deep Learning with RNA-seq | OpDetect [37] | Raw RNA-seq reads, Nucleotide-level signals | Species-agnostic capabilities, Superior recall and F1 scores | Complex implementation, Computational intensity |

| Methyl ganoderenate D | Methyl ganoderenate D, MF:C31H42O7, MW:526.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| Daidzein-4'-glucoside | Daidzein-4'-glucoside|High-Purity Reference Standard | Daidzein-4'-glucoside is a soy isoflavone metabolite for research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human, veterinary, or household use. | Bench Chemicals |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Validation

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Rigorous evaluation of operon prediction tools requires standardized metrics and benchmarking datasets. Independent comparative studies have quantified the performance of various algorithms using experimentally verified operon annotations as ground truth.

OpDetect demonstrates superior performance with an F1-score of 0.91 and AUROC of 0.95, outperforming other contemporary tools on independent validation datasets. Its convolutional and recurrent neural network architecture effectively captures spatial and sequential dependencies in RNA-seq data across nucleotide positions [37].

OperonSEQer achieves robust performance through its ensemble approach, with individual algorithms in its framework showing F1-scores ranging from 0.79 to 0.87 when trained on diverse bacterial species including both Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms with varying GC content [19].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Modern Operon Prediction Tools

| Tool | Recall | Precision | F1-Score | AUROC | Organisms Validated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OpDetect [37] | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 7 bacteria + C. elegans |

| OperonSEQer [19] | 0.81-0.89* | 0.78-0.86* | 0.79-0.87* | N/R | 8 bacterial species |

| Rockhopper [36] | N/R | N/R | N/R | N/R | Multiple species |

| Operon-mapper [37] | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.89 | E. coli, B. subtilis |

*Range across six different machine learning algorithms in the framework

Experimental Validation Protocols

Experimental validation remains essential for confirming computational predictions, particularly for novel or unexpected operon structures.

- Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR): A widely adopted method for experimental operon validation involves extracting total RNA under appropriate growth conditions, followed by DNase treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination. Reverse transcription is performed using gene-specific primers or random hexamers, with subsequent PCR amplification using primers spanning intergenic regions. Successful amplification of fragments crossing gene boundaries provides strong evidence of cotranscription [34].

- Long-Read RNA Sequencing: Emerging validation approaches utilize long-read sequencing technologies (e.g., Oxford Nanopore) that can directly sequence full-length transcripts, providing unambiguous evidence of operon structures. These methods are particularly valuable for benchmarking the performance of computational prediction tools [19].

- Cross-Species Validation: Robust benchmarking involves applying prediction tools to organisms not included in training datasets. For instance, OpDetect was validated on six bacterial species and Caenorhabditis elegans (one of few eukaryotes with operons) that were excluded from model training, demonstrating its species-agnostic capabilities [37].

Computational Workflows and Data Processing

The accuracy of operon prediction depends critically on proper data processing and analytical workflows, particularly for methods utilizing RNA-seq data.

Operon Prediction Computational Workflow

RNA-seq Data Processing Pipeline

Standardized preprocessing of RNA-seq data is essential for reliable operon prediction:

- Read Trimming and Filtering: Tools like Fastp remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences, significantly impacting downstream assembly and prediction quality [37].

- Genome Alignment: Processed reads are aligned to reference genomes using aligners such as HISAT2 or Bowtie2 with parameters optimized for prokaryotic genomes (e.g., disabling spliced alignment) [38] [37].

- Feature Extraction: Depending on the prediction algorithm, features may include read coverage vectors across genes and intergenic regions, Kruskal-Wallis statistics comparing coverage distributions, or raw nucleotide-level signals resampled to fixed-size inputs [19] [37].

Genome Assembly Considerations

For novel genomes without established references, assembly quality directly impacts operon prediction accuracy. Recent benchmarking of long-read assemblers using Escherichia coli DH5α data demonstrated that preprocessing strategies and assembler selection significantly affect assembly contiguity and completeness. NextDenovo and NECAT produced the most complete, contiguous assemblies, while Flye provided the best balance of accuracy, speed, and assembly integrity [39].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of operon prediction pipelines requires both laboratory reagents and bioinformatics tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Operon Prediction and Validation

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose | Example Tools/Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Laboratory Reagents | RNA extraction kits, DNase I, Reverse transcriptase, PCR reagents, Long-read sequencing kits | Experimental validation of predicted operons via RT-PCR and direct RNA sequencing | RT-PCR protocols [34], Oxford Nanopore sequencing [19] |

| Reference Databases | OperonDB, ProOpDB, RegulonDB, MicrobesOnline | Source of experimentally validated operons for training and benchmarking | OperonDB v4 [37], ProOpDB [37] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Fastp, HISAT2, Bowtie2, SAMtools, BEDTools | Preprocessing, alignment, and feature extraction from RNA-seq data | SAMtools v1.17 [37], BEDtools v2.30.0 [37] |

| Specialized Operon Predictors | OpDetect, OperonSEQer, Rockhopper, Operon-mapper | Implementation of specific prediction algorithms | OpDetect [37], OperonSEQer [19] |

The evolution of operon prediction methodologies has progressively enhanced our ability to accurately identify transcriptional units across diverse prokaryotic genomes. Sequence-based and comparative genomics approaches provide maximum portability for newly sequenced organisms but offer limited sensitivity. Machine learning methods leveraging RNA-seq data deliver higher accuracy, with deep learning approaches like OpDetect representing the current state-of-the-art in terms of recall and species-agnostic performance. Selection of appropriate prediction tools should be guided by research objectives, data availability, and required precision, with experimental validation remaining essential for confirming novel operon structures, particularly those with potential implications for understanding bacterial pathogenesis or metabolic engineering.

In-Depth Review of Standalone Tools and Integrated Annotation Pipelines

The exponential growth in available prokaryotic genomes, derived from both isolates and metagenomic assemblies, has heightened the need for efficient and accurate genomic annotation pipelines. In the specific context of benchmarking operon prediction algorithms, the choice of annotation tools is paramount, as operon identification relies heavily on precise gene calling, functional annotation, and understanding genomic context. Annotation pipelines have evolved from standalone, specialized tools to integrated, containerized solutions that combine multiple analytical steps into cohesive workflows. These pipelines are critical for researchers and drug development professionals who require comprehensive, reproducible, and scalable annotations to drive discoveries in microbial genomics. This review provides an objective comparison of current standalone and integrated annotation pipelines, evaluating their performance, features, and applicability to operon prediction within a prokaryotic genomics research framework.

Integrated annotation pipelines consolidate multiple tools into a single workflow, handling tasks from gene prediction to functional annotation and visualization. The design and capabilities of these pipelines directly influence the quality of downstream analyses, including operon prediction.

CompareM2 is a genomes-to-report pipeline designed for the comparative analysis of bacterial and archaeal genomes from both isolates and metagenomic assemblies. Its priority is ease of use, featuring a single-step installation and the ability to launch all analyses in a single action. It is scalable to various project sizes and produces a portable dynamic report document highlighting central results. Technically, CompareM2 performs quality control (using CheckM2), functional annotation (using Bakta or Prokka), and advanced annotation via specialized tools for tasks like identifying carbohydrate-active enzymes (dbCAN), building metabolic models (Gapseq), and finding biosynthetic gene clusters (Antismash). For phylogenetic analysis, it employs tools like Mashtree and Panaroo. Its installation is streamlined through containerization, and it can automatically download and integrate RefSeq or GenBank genomes as references. Benchmarking indicates that CompareM2 scales efficiently, with running time increasing approximately linearly even with input sizes exceeding the number of available machine cores, outperforming tools like Tormes and Bactopia in speed [40].

mettannotator is a comprehensive, scalable Nextflow pipeline that addresses the challenge of annotating novel species poorly represented in reference databases. It identifies coding and non-coding regions, predicts protein functions (including antimicrobial resistance), and delineates gene clusters, consolidating results into a single GFF file. A key feature is its use of the UniProt Functional annotation Inference Rule Engine (UniFIRE) to assign functions to unannotated proteins. It also predicts larger genomic regions like biosynthetic gene clusters and anti-phage defence systems. The pipeline is containerized, follows FAIR principles, and is compatible with Linux systems. Performance evaluations show that in its "fast" mode (skipping InterProScan, UniFIRE, and SanntiS), it averages around 4 hours per genome, offering a balance between depth and speed [41].