Benchmarking Bioinformatics Pipelines for Microbiome Data: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust and Reproducible Analysis

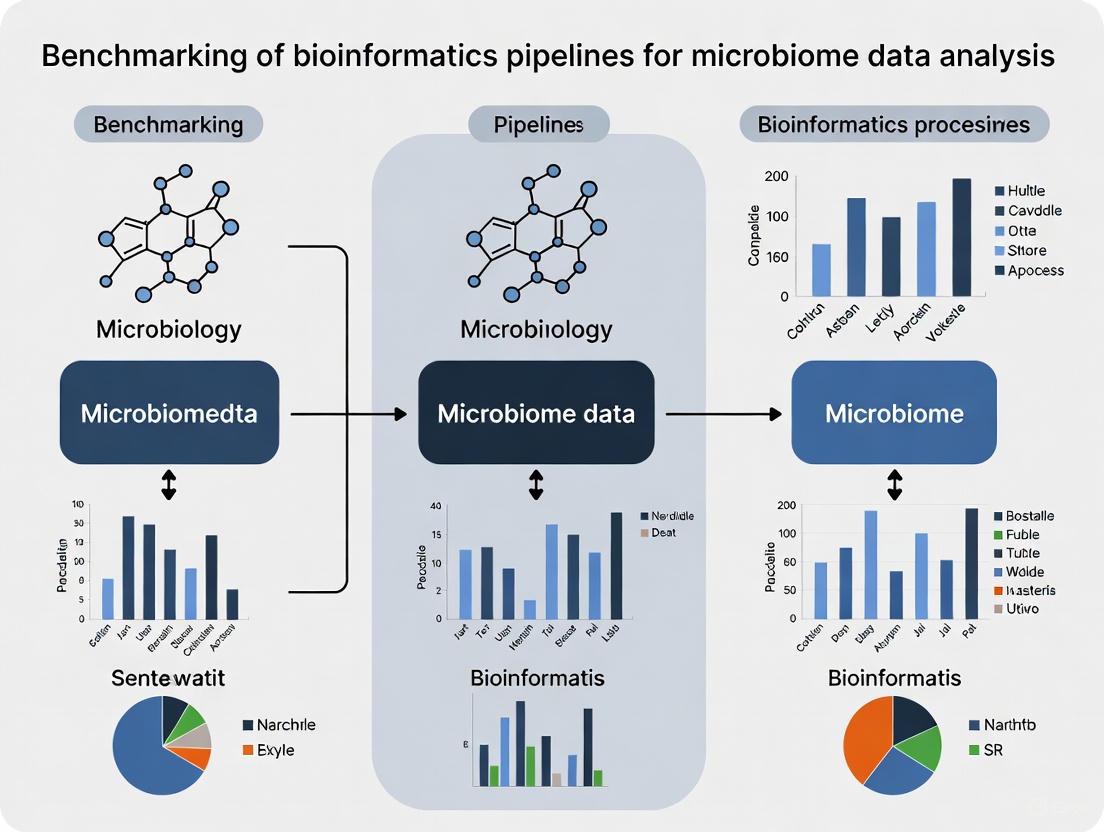

This article provides a systematic benchmark and practical guide for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the complex landscape of microbiome bioinformatics pipelines.

Benchmarking Bioinformatics Pipelines for Microbiome Data: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust and Reproducible Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a systematic benchmark and practical guide for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the complex landscape of microbiome bioinformatics pipelines. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, we synthesize the latest 2024-2025 research on pipeline performance, integration strategies, and validation frameworks. Drawing from recent large-scale benchmarking studies, we detail optimal methods for differential abundance testing, multi-omic integration, and clinical translation. The content addresses critical challenges including data standardization, confounder adjustment, and computational reproducibility, while offering evidence-based recommendations for selecting and optimizing pipelines based on specific research goals and data types. This resource aims to establish best practices that enhance reliability and translational potential in microbiome research.

The Critical Need for Benchmarking in Microbiome Bioinformatics

Microbiome data, derived from high-throughput sequencing technologies, are foundational to modern biological and clinical research. However, their unique characteristics pose significant challenges for statistical analysis and biological interpretation. Effective research requires navigating three core challenges: compositionality, sparsity, and technical variability [1] [2] [3]. This guide objectively compares the performance of analytical methods designed to address these issues, providing a framework for selecting optimal bioinformatics pipelines in benchmarking studies.

The Core Triad of Microbiome Data Challenges

The analytical challenges of microbiome data stem from its fundamental properties:

- Compositionality: Sequencing data represent relative, not absolute, abundances. The total number of reads per sample (library size) is a technical constraint, meaning an increase in one taxon's count inevitably causes a decrease in the observed counts of others [1] [3]. Analyzing such data with standard statistical methods can produce spurious correlations [4].

- Sparsity (Zero-Inflation): Microbiome datasets contain a high proportion of zero counts, often between 80% and 95% [5] [3]. These zeros can represent either true biological absence or technical artifacts (e.g., low abundance below detection limit), making distinguishing between them a major challenge [5].

- Technical Variability: Sources like variable sequencing depth, DNA extraction efficiency, and batch effects introduce non-biological noise that can obscure true biological signals and lead to false conclusions if not corrected [1] [3].

The following diagram illustrates the interrelationships between these challenges and the primary strategies for mitigating them.

Comparative Performance of Analytical Methods

Normalization and Transformation Techniques

Normalization is a critical first step to account for variable sequencing depths and compositionality. The table below summarizes common techniques and their performance characteristics.

| Method | Primary Approach | Handling of Zeros | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sum Scaling (TSS) | Converts counts to proportions | Problematic; alters proportions | Simple and intuitive | Reinforces compositionality [3] |

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) | Log-transforms relative to geometric mean | Requires pseudo-counts | Compositionally aware [4] | Interpretation is relative [1] [4] |

| Isometric Log-Ratio (ILR) | Log-ratio between orthonormal balances | Requires imputation | Full compositionality control [4] | Complex interpretation [4] |

| Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS) | Scales by cumulative sum up to a percentile | Robust to low counts | Robust to high sparsity [3] | Less common in newer tools |

| Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) | Scales by weighted mean of log-ratios | Uses only non-zero counts | Robust to compositionally and outliers [5] [3] | Designed for RNA-seq; borrowed for microbiome |

Differential Abundance Analysis Tools

Detecting taxa that differ between conditions is a common goal. Benchmarks reveal that no single method excels in all scenarios; performance depends on data characteristics like zero inflation and effect size [5] [3].

| Tool | Underlying Model | Handles Compositionality | Handles Sparsity | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Negative Binomial with regularization | Via normalization (e.g., RLE) | Good; penalized likelihood for group-wise zeros [5] | High accuracy with controlled FDR; struggles with very high zero-inflation [5] [3] |

| edgeR | Negative Binomial | Via normalization (e.g., TMM) | Moderate | Good power; can be prone to false positives with complex sparsity [5] [3] |

| ALDEx2 | Dirichlet-Multinomial & CLR | Yes (inherently via CLR) | Moderate via pseudo-counts | Robust to compositionality; good FDR control [5] [3] |

| ANCOM | Log-ratio based null hypothesis | Yes (inherently) | Uses a prevalence filter | Very low false positive rate; can be conservative [3] |

| DESeq2-ZINBWaVE | Negative Binomial with ZINBWaVE weights | Via normalization | Excellent; uses observation weights for zero-inflation [5] | Effectively controls false discoveries in zero-inflated data [5] |

A combined approach using DESeq2-ZINBWaVE for general zero-inflation followed by standard DESeq2 for taxa with group-wise structured zeros (all zeros in one group) has been demonstrated to outperform either method used alone [5].

Integrative Analysis for Microbiome-Metabolome Data

Integrating microbiome data with other omics layers, like metabolomics, requires methods that can handle the complexities of both data types. A 2025 benchmark study evaluated 19 integrative strategies [4].

| Research Goal | Top-Performing Methods | Key Findings from Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| Global Association (Testing overall link between datasets) | MMiRKAT, Mantel test | Methods maintained correct Type-I error control and were powerful for detecting global associations [4]. |

| Data Summarization (Identifying major joint patterns) | sPLS (sparse PLS), MOFA+ | sPLS effectively recovered known correlations between specific microbes and metabolites in real data [4]. |

| Individual Associations (Finding specific microbe-metabolite pairs) | Sparse CCA (sCCA), Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) | GLMs with proper CLR transformation performed well for identifying individual links [4]. |

| Feature Selection (Selecting the most important features) | LASSO, sPLS | These methods successfully identified stable, non-redundant sets of associated microbes and metabolites [4]. |

The benchmark concluded that transforming microbiome data with CLR or ILR before analysis was crucial for obtaining reliable results with most methods [4].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure fair and reproducible comparisons, benchmarking studies must use robust simulation frameworks and standardized evaluation metrics.

Simulation and Validation Workflow

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive benchmarking workflow, synthesizing protocols from several key studies.

Protocol 1: Realistic Data Simulation using NORtA

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 benchmark of microbiome-metabolome integrative methods [4].

- Template Selection: Use a real microbiome-metabolome dataset (e.g., from a public repository) as a template to estimate realistic parameters, including:

- Marginal distributions (e.g., Negative Binomial for microbiome, Poisson or log-normal for metabolome).

- Correlation structures within and between omics layers, estimated using tools like

SpiecEasi[4].

- Data Generation: Employ the NORtA (NORmal To Anything) algorithm to generate synthetic datasets that preserve the estimated correlation structures and marginal distributions of the real template data [4].

- Scenario Design:

- Null Scenario: Simulate datasets with no pre-defined associations to assess Type-I error control (false positive rate).

- Alternative Scenarios: Introduce known associations between a specific set of microorganisms and metabolites. Vary parameters like sample size, strength of association, and feature dimensionality to test method robustness [4].

- Replication: Generate a large number of replicate datasets (e.g., N=1000) for each scenario to ensure statistical reliability of performance metrics [4].

Protocol 2: Mock Community Experiments for Validation

For wet-lab validation, benchmark using constructed mock communities, as demonstrated in a 2025 metatranscriptomics study [6].

- Community Formulation:

- Select a panel of microbial strains relevant to the study environment (e.g., marine, soil, human gut).

- Create two types of mock samples:

- Cell-mixed: Combine cells from different strains before RNA/DNA extraction. This captures biases from nucleic acid extraction efficiency.

- RNA/DNA-mixed: Extract nucleic acids from each strain individually and then combine them in predefined ratios. This provides a more precise ground truth for abundance [6].

- Define Ground Truth: Mix strains with varying "evenness"—equal abundance for some, highly skewed abundances for others—to test performance across diverse community structures [6].

- Sequencing and Analysis: Process mock communities using standard sequencing protocols (e.g., Illumina HiSeq). Analyze the resulting data with the tools being benchmarked.

- Metric Calculation: Compare the tool's output (e.g., estimated species abundance, detected differentially abundant features) to the known ground truth to calculate accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity [6].

| Category | Item | Function in Microbiome Research |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Software | QIIME2, Mothur, DADA2 | Processing raw sequencing reads into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) or OTUs [1] [7]. |

| Analysis Platforms | MicrobiomeAnalyst | User-friendly web-based platform for comprehensive statistical, visual, and functional analysis of microbiome data [1] [7]. |

| Statistical Environments | R/Bioconductor | Provides access to a vast ecosystem of packages for differential abundance (DESeq2, edgeR), integration (mixOmics), and more [1] [3]. |

| Reference Materials | Mock Microbial Communities | Assembled mixtures of known microorganisms with defined abundances, used as positive controls and for benchmarking pipeline accuracy [6]. |

| Specialized Kits | rRNA Depletion Kits | Critical for metatranscriptomic studies to remove abundant ribosomal RNA and enrich for messenger RNA, enabling gene expression profiling [6]. |

A significant challenge in microbiome research is the lack of standardized bioinformatics protocols, leading to a fragmented landscape where analytical choices can directly impact biological interpretations. This guide objectively compares the performance of prevalent bioinformatics pipelines and differential abundance methods, synthesizing findings from recent, large-scale benchmarking studies to provide clarity for researchers.

Experimental Comparison of Core Bioinformatics Pipelines

A 2025 study directly compared three widely used bioinformatics packages—DADA2, MOTHUR, and QIIME2—to assess the reproducibility of microbiome composition analysis [8].

- Experimental Protocol: Five independent research groups analyzed the same dataset of 16S rRNA gene raw sequencing data (V1-V2 region) from gastric biopsy samples. The cohort included 40 gastric cancer patients (with and without Helicobacter pylori infection) and 39 controls. Each group processed the identical subset of fastQ files using one of the three distinct bioinformatic packages [8].

- Key Findings: The study concluded that core findings, such as H. pylori status, microbial diversity, and relative bacterial abundance, were reproducible across all three platforms despite differences in their underlying algorithms [8]. This suggests that for fundamental taxonomic profiling, these robust pipelines can yield comparable results.

The table below summarizes the experimental design and primary conclusion:

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Compared Pipelines | DADA2, MOTHUR, QIIME2 [8] |

| Source Data | 16S rRNA gene sequencing (V1-V2) from 79 gastric biopsy samples [8] |

| Experimental Design | Analysis of the same fastQ files by five independent research groups using different packages [8] |

| Core Finding | H. pylori status, microbial diversity, and relative abundance were reproducible across platforms [8] |

Benchmarking Differential Abundance Methods

The fragmentation issue is more pronounced in differential abundance (DA) testing. A 2022 benchmark of 14 DA methods across 38 real-world 16S rRNA datasets revealed substantial inconsistencies in their outputs [9].

- Experimental Protocol: The study applied 14 different DA testing approaches to 38 datasets from environments including the human gut, soil, and marine ecosystems (total of 9,405 samples). Methods tested included ALDEx2, ANCOM-II, DESeq2, edgeR, LEfSe, limma voom, metagenomeSeq, and Wilcoxon test on CLR-transformed data, among others. Performance was evaluated based on the number and set of significant Amplicon Sequence Variants identified, with and without prevalence filtering of rare taxa [9].

- Key Findings: The study found that different methods identified "drastically different numbers and sets of significant" features. The percentage of significant ASVs varied widely across methods, and the number of features identified by a given tool often correlated with dataset characteristics like sample size and sequencing depth [9].

The following workflow diagrams the experimental process and core findings of these critical benchmarking studies:

The table below summarizes the performance of selected differential abundance methods based on the benchmark:

| Method | Reported Performance & Characteristics |

|---|---|

| ALDEx2 | Produced consistent results across studies; agreed well with the intersect of different methods [9]. |

| ANCOM-II | Produced consistent results across studies; agreed well with the intersect of different methods [9]. |

| limma voom (TMMwsp) | Identified a high number of significant ASVs in some datasets, but results were highly variable [9]. |

| edgeR | Tended to find a high number of significant ASVs; has been shown to have high false positive rates in some evaluations [9]. |

| LEfSe | A popular method that often requires rarefied count tables, which can affect statistical power [9]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

This table details key software and analytical solutions central to conducting and benchmarking microbiome analyses.

| Item Name | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| DADA2, QIIME2, MOTHUR | Core bioinformatics packages for processing raw sequencing data into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) or Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) [8]. |

| ALDEx2 | A differential abundance tool that uses a compositional data analysis approach (Centered Log-Ratio transformation) to account for the compositional nature of sequencing data [9]. |

| ANCOM-II | A differential abundance method designed to handle compositionality by using additive log-ratio transformations [9]. |

| LEfSe | A tool for identifying differentially abundant features that also incorporates biological class comparisons and effect size estimation [10]. |

| DESeq2 & edgeR | Statistical frameworks originally designed for RNA-seq data, adapted for microbiome differential abundance testing by modeling read counts with a negative binomial distribution [9]. |

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) Transformation | A compositional data transformation used to address the compositional nature of microbiome data before applying standard statistical models [4] [9]. |

| NHS ester-PEG3-S-methyl ethanethioate | NHS ester-PEG3-S-methyl ethanethioate, MF:C15H23NO8S, MW:377.4 g/mol |

| Trimetazidine-N-oxide | Trimetazidine-N-oxide, MF:C14H22N2O4, MW:282.34 g/mol |

Recommendations for Robust Analysis

Based on the empirical evidence, researchers can adopt several strategies to enhance the reliability of their findings:

- Adopt a Consensus Approach: For differential abundance analysis, using multiple methods and focusing on the intersecting results can lead to more robust and reliable biological interpretations [9].

- Select Robust Pipelines: For standard taxonomic profiling, established pipelines like DADA2, QIIME2, and MOTHUR can produce reproducible core results, provided the analysis is thoroughly documented [8].

- Acknowledge Methodological Influence: The choice of bioinformatic methods and pre-processing steps should be clearly documented and reported, as they are a significant source of variation that can influence scientific conclusions and the translational potential of results [8] [9].

Key Research Questions Driving Pipeline Development and Evaluation

The exponential growth of microbiome research has been fueled by advancements in high-throughput sequencing technologies, generating vast amounts of complex biological data. This deluge of information has necessitated the development of sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines to transform raw sequencing data into interpretable biological insights. However, the multiplicity of available analytical frameworks presents a significant challenge for researchers seeking to identify optimal strategies for their specific research objectives. The critical importance of pipeline selection stems from its profound impact on result interpretation, reproducibility, and the validity of biological conclusions. This comparison guide examines the key research questions driving pipeline development and evaluation, providing an evidence-based framework for selecting appropriate analytical strategies in microbiome research.

Key Research Questions in Pipeline Evaluation

The development and refinement of bioinformatics pipelines are guided by fundamental research questions that address different aspects of analytical performance and biological relevance. Through systematic benchmarking studies, four primary categories of research questions have emerged as critical for pipeline evaluation.

Data Fidelity and Taxonomic Accuracy

How accurately does a pipeline recover true microbial composition and diversity from complex samples? This foundational question addresses the core function of taxonomic classification and abundance estimation.

Experimental Approach: Researchers typically employ simulated microbial communities with known composition or standardized mock communities to establish ground truth. For example, one benchmarking study simulated metagenomes containing foodborne pathogens at defined relative abundance levels (0.01%, 0.1%, 1%, and 30%) within various food matrices to evaluate classification accuracy [11]. This controlled approach allows for precise measurement of a pipeline's ability to detect target organisms across abundance gradients.

Evaluation Metrics: Performance is quantified using standard classification metrics including sensitivity (recall), precision, F1-score (harmonic mean of precision and recall), and false discovery rates. These metrics provide comprehensive assessment of taxonomic assignment accuracy across different abundance thresholds.

Cross-Platform Reproducibility

To what extent do different pipelines applied to the same dataset yield consistent biological conclusions? This question addresses the critical issue of reproducibility and comparability across studies.

Experimental Approach: Studies directly compare multiple bioinformatics pipelines applied to identical datasets. One comprehensive investigation analyzed 40 human fecal samples using four popular pipelines (QIIME2, Bioconductor, UPARSE, and mothur) run on two different operating systems [12]. The researchers then compared taxonomic classifications at both phylum and genus levels to assess consistency across platforms.

Key Findings: The study revealed that while different pipelines showed consistent patterns in taxa identification, they produced statistically significant differences in relative abundance estimates. For instance, the genus Bacteroides showed abundance variations ranging from 20.6% to 24.6% depending on the pipeline used [12]. Such discrepancies highlight the challenges in cross-study comparisons and meta-analyses when different analytical workflows are employed.

Computational Efficiency and Scalability

How do pipelines perform in terms of computational resource requirements, processing speed, and scalability to large datasets? This practical consideration becomes increasingly important as study sizes grow.

Experimental Approach: Benchmarking studies measure wall-clock time, memory usage, and CPU utilization across pipelines while processing datasets of varying sizes. For example, CompareM2 was evaluated against Tormes and Bactopia by measuring processing times with increasing input genomes [13]. Performance was assessed on a 64-core workstation with 32 cores allocated for the analysis to ensure consistent benchmarking conditions.

Performance Considerations: The architectural design significantly impacts computational efficiency. CompareM2 demonstrated approximately linear scaling with increasing input size, outperforming alternatives that process samples sequentially rather than in parallel [13]. Pipeline design choices, such as the need to generate artificial reads for certain analyses, also substantially affect processing time.

Functional and Ecological Inference

How effectively can pipelines move beyond taxonomic classification to infer functional potential and ecological interactions? This question addresses the growing interest in moving from descriptive to mechanistic understanding of microbial communities.

Experimental Approach: Advanced pipelines incorporate functional annotation tools that predict metabolic capabilities, antimicrobial resistance genes, virulence factors, and biosynthetic gene clusters. CompareM2, for instance, integrates multiple functional annotation tools including InterProScan (protein signature databases), dbCAN (carbohydrate-active enzymes), Eggnog-mapper (orthology-based annotations), gapseq (metabolic modeling), and antiSMASH (biosynthetic gene clusters) [13].

Integration Capabilities: The ability to integrate multi-omics data represents a cutting-edge capability in pipeline development. Methodologies for integrating microbiome data with metabolomic profiles are particularly valuable for elucidating microbe-metabolite relationships [4]. Such integration enables researchers to address complex questions about how microbial community composition influences metabolic processes relevant to health and disease.

Comparative Performance of Bioinformatics Pipelines

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Taxonomic Classification Tools for Pathogen Detection

| Tool | Detection Limit | Overall Accuracy (F1-Score) | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kraken2/Bracken | 0.01% abundance | Highest across all food matrices | Broadest detection range, consistent performance | - |

| Kraken2 | 0.01% abundance | High | Excellent sensitivity for low-abundance taxa | Slightly lower accuracy than Kraken2/Bracken |

| MetaPhlAn4 | >0.01% abundance | Variable across abundance levels | Strong performance for specific pathogens (e.g., C. sakazakii) | Limited detection at lowest abundances (0.01%) |

| Centrifuge | >0.01% abundance | Lowest among tested tools | - | High limit of detection, suboptimal performance |

Data derived from benchmarking study on pathogen detection in food metagenomes [11].

Table 2: Comparison of 16S rRNA Amplicon Analysis Pipelines

| Pipeline | Methodology | OS Consistency | Relative Abundance Variation | Computational Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QIIME2 | ASV (DADA2, Deblur) | Identical output (Linux vs. Mac) | Bacteroides: 24.5% | Moderate to high |

| Bioconductor | ASV (DADA2) | Identical output (Linux vs. Mac) | Bacteroides: 24.6% | Moderate |

| UPARSE | OTU (97% similarity) | Minimal differences between OS | Bacteroides: 20.6-23.6% | Lower |

| mothur | OTU (97% similarity) | Minimal differences between OS | Bacteroides: 21.6-22.2% | Lower |

Data from comparison of 40 human fecal samples analyzed across four pipelines and two operating systems [12].

Experimental Protocols for Pipeline Benchmarking

Standardized experimental approaches are essential for rigorous pipeline evaluation. The following methodologies represent current best practices in the field.

Simulated Community Design

Benchmarking studies frequently employ simulated microbial communities with known composition to establish ground truth. The simulation process involves:

Template Selection: Real microbiome datasets inform simulation parameters. One comprehensive benchmarking study used three real datasets as templates: Konzo dataset (171 samples, 1,098 taxa, 1,340 metabolites), Adenomas dataset (240 samples, 500 taxa, 463 metabolites), and Autism spectrum disorder dataset (44 samples, 322 taxa, 61 metabolites) [4].

Data Generation: The Normal to Anything (NORtA) algorithm generates data with arbitrary marginal distributions and correlation structures, preserving the statistical properties of real microbiome data [4]. This approach maintains characteristic features such as over-dispersion, zero-inflation, and high collinearity between taxa.

Abundance Spike-ins: Pathogens or target taxa are introduced at defined relative abundance levels (e.g., 0%, 0.01%, 0.1%, 1%, 30%) to establish detection limits and accuracy across abundance gradients [11].

Cross-Pipeline Validation

When comparing multiple pipelines, consistent processing parameters are essential:

Reference Database Standardization: All pipelines should utilize the same reference database (e.g., SILVA 132) to isolate pipeline effects from database biases [12].

Operating System Controls: Running pipelines on multiple operating systems (Linux and Mac OS) controls for potential OS-specific effects on computational results [12].

Statistical Analysis: Non-parametric tests (e.g., Friedman rank sum test) compare relative abundance estimates across pipelines, identifying statistically significant differences in taxonomic assignments [12].

Performance Metrics and Evaluation

Comprehensive benchmarking employs multiple evaluation metrics:

Classification Accuracy: Standard metrics including sensitivity, precision, F1-scores, and false discovery rates provide quantitative assessment of taxonomic assignment performance [11].

Biological Consistency: The ability to discriminate samples by treatment group or clinical status, despite differences in absolute abundance values, assesses whether pipelines yield consistent biological conclusions [14].

Computational Efficiency: Processing time, memory usage, and scalability measurements provide practical guidance for researchers with limited computational resources [13].

Workflow Diagram: Pipeline Benchmarking Process

Multi-Omics Integration Framework

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pipeline Benchmarking

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | E.Z.N.A. Stool DNA Kit | Efficient DNA isolation from complex samples | Standardized DNA extraction for cross-study comparisons [14] |

| Quality Control | CheckM2 | Computes completeness and contamination parameters | Genome quality assessment in comparative analyses [13] |

| Taxonomic Classification | GTDB-Tk | Taxonomic assignment using alignment of ubiquitous proteins | Standardized taxonomy across diverse microbial genomes [13] |

| Functional Annotation | Bakta/Prokka | Rapid genome annotation | Functional potential assessment of microbial communities [13] |

| Pathogen Detection | AMRFinder | Scans for antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factors | Clinical and food safety applications [13] |

| Metabolic Modeling | gapseq | Builds gapfilled genome scale metabolic models | Prediction of metabolic capabilities from genomic data [13] |

| Biosynthetic Gene Clusters | antiSMASH | Identifies biosynthetic gene clusters | Natural product discovery and functional potential [13] |

| Database Resources | SILVA database | Curated ribosomal RNA database | Taxonomic classification standard for 16S rRNA studies [12] |

The evaluation of bioinformatics pipelines for microbiome research is guided by fundamental questions addressing accuracy, reproducibility, efficiency, and biological relevance. Evidence from systematic benchmarking studies reveals that pipeline selection significantly impacts research outcomes, with different tools exhibiting distinct strengths and limitations. Kraken2/Bracken demonstrates superior performance for sensitive pathogen detection, while pipelines like QIIME2 and Bioconductor provide robust solutions for amplicon sequencing analysis despite producing variations in relative abundance estimates. The growing emphasis on multi-omics integration further expands the evaluation framework to include methods that elucidate relationships between microorganisms and metabolites. As the field advances, standardized benchmarking approaches and comprehensive performance assessments will continue to drive pipeline development, ultimately enhancing the reliability and biological relevance of microbiome research.

Impact of Analytical Variability on Scientific Reproducibility and Clinical Translation

The clinical translation of microbiome research represents a paradigm shift in understanding disease etiology and therapeutic design [15]. However, this promising field faces a significant hurdle: analytical variability. The complexity of bioinformatics pipelines, encompassing multiple stages with numerous parameters, provides researchers with considerable flexibility but also introduces substantial challenges for reproducibility and reliable clinical translation [16]. This variability is not unique to microbiome research; a 2025 study demonstrated that when more than 300 scientists independently analyzed the same dataset, their methodological choices led to highly variable conclusions, raising fundamental questions about the reliability of scientific results [17]. Such variability directly impacts the identification of microbial biomarkers, the assessment of therapeutic efficacy, and the development of robust clinical diagnostics [15] [18] [19].

The inherent characteristics of microbiome data—including compositionality, high dimensionality, and significant batch effects—further complicate analysis and necessitate careful methodological considerations [18] [19]. As the field moves toward clinical applications, understanding and mitigating the impact of analytical variability becomes paramount. This guide objectively compares the performance of leading bioinformatics pipelines, evaluates experimental data on their reproducibility, and provides a structured framework for benchmarking these tools in microbiome research.

Comparative Performance of Metagenomic Classification Tools

Benchmarking Foodborne Pathogen Detection

The performance of bioinformatics tools varies significantly across different applications and scenarios. A comprehensive benchmarking study evaluated four metagenomic classification tools for detecting foodborne pathogens in simulated microbial communities representing three food products [11]. Researchers simulated metagenomes containing Campylobacter jejuni, Cronobacter sakazakii, and Listeria monocytogenes at defined relative abundance levels (0%, 0.01%, 0.1%, 1%, and 30%) within respective food microbiomes [11].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Metagenomic Classification Tools for Pathogen Detection

| Tool | Overall Accuracy | Detection Limit | Best Use Case | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kraken2/Bracken | Highest classification accuracy, consistently high F1-scores across all food metagenomes [11] | 0.01% abundance [11] | Broad-spectrum pathogen detection in complex matrices [11] | - |

| Kraken2 | High accuracy, broad detection range [11] | 0.01% abundance [11] | Scenarios requiring sensitive detection without abundance estimation [11] | - |

| MetaPhlAn4 | Performed well, particularly for C. sakazakii in dried food [11] | Limited detection at 0.01% abundance [11] | Targeted analysis of specific pathogens with moderate abundance [11] | Higher limit of detection compared to Kraken2/Bracken [11] |

| Centrifuge | Exhibited the weakest performance across food matrices and abundance levels [11] | Higher limit of detection [11] | - | Underperformed across various conditions [11] |

The study demonstrated that tool selection significantly impacts detection capabilities, particularly at low pathogen abundances relevant to clinical and public health applications [11]. The Kraken2/Bracken combination emerged as the most effective tool for sensitive pathogen detection, while MetaPhlAn4 served as a valuable alternative depending on pathogen prevalence and abundance [11].

Reproducibility Across 16S rRNA Gene Analysis Pipelines

Beyond metagenomic tools, the reproducibility of 16S rRNA gene analysis pipelines is equally crucial for clinical translation. A 2025 comparative study investigated how different microbiome analysis platforms impact results from gastric mucosal microbiome samples [8]. Five independent research groups applied three commonly used bioinformatics packages (DADA2, MOTHUR, and QIIME2) to the same dataset of 16S rRNA gene sequences from gastric biopsy samples [8].

Table 2: Reproducibility of Microbiome Analysis Platforms for Gastric Mucosal Samples

| Analysis Aspect | DADA2 | MOTHUR | QIIME2 | Overall Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. pylori status | Reproducible across platforms [8] | Reproducible across platforms [8] | Reproducible across platforms [8] | High [8] |

| Microbial diversity | Reproducible across platforms [8] | Reproducible across platforms [8] | Reproducible across platforms [8] | High [8] |

| Relative bacterial abundance | Reproducible across platforms [8] | Reproducible across platforms [8] | Reproducible across platforms [8] | High [8] |

| Taxonomic assignment (different databases) | Limited impact on outcomes [8] | Limited impact on outcomes [8] | Limited impact on outcomes [8] | High [8] |

Despite differences in performance metrics, the core biological conclusions remained consistent across platforms and research groups [8]. This reproducibility underscores the broader applicability of microbiome analysis in clinical research, provided that robust, well-documented pipelines are utilized [8].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Bioinformatics Pipelines

Standardized Benchmarking Methodology

Rigorous benchmarking requires standardized methodologies to ensure fair and informative comparisons between computational tools. Best practices for developing and benchmarking computational methods for microbiome analysis include [19]:

Test Data Selection: Benchmarking datasets should reflect the intended use cases and include simulated communities with known composition, mock communities, and well-characterized clinical samples [19]. The data must represent the diversity of sample types or species a method is intended to address [19].

Performance Metrics: Multiple evaluation metrics should be incorporated, including sensitivity, specificity, precision, recall, F1-score, computational efficiency (runtime and memory requirements), and scalability [19].

Benchmarking Approaches:

- Internal benchmarking: Performed by method developers to optimize and validate new tools [19]

- Neutral benchmarks: Conducted by researchers not involved in tool development to provide unbiased evaluation [19]

- Community challenges: Large-scale collaborations ensuring proper implementation of multiple methods [19]

Data Characteristics Consideration: Benchmarks must account for unique properties of microbiome data, including compositionality, high sparsity, variable sequencing depth, and batch effects [19].

Experimental Design for Pipeline Comparison

The experimental protocol used in the gastric microbiome study provides a robust template for pipeline comparisons [8]:

Sample Collection and Processing: Gastric biopsy samples were collected from clinically well-defined gastric cancer patients (n=40; with and without Helicobacter pylori infection) and controls (n=39, with and without H. pylori infection) [8].

Sequencing: 16S rRNA gene sequencing of the V1-V2 regions was performed on all samples, generating raw FASTQ files for analysis [8].

Independent Analysis: Five research groups independently analyzed the same subset of FASTQ files using DADA2, MOTHUR, and QIIME2 with their preferred parameters [8].

Taxonomic Classification: Filtered sequences were aligned against both old and new taxonomic databases (Ribosomal Database Project, Greengenes, and SILVA) to evaluate database impact [8].

Output Comparison: Results for H. pylori status, microbial diversity, and relative bacterial abundance were compared across platforms to assess reproducibility [8].

This experimental design highlights that consistent results can be achieved across platforms when analyzing the same underlying data, supporting the validity of microbiome analysis for clinical research [8].

Visualizing Analytical Variability and Its Impact

The relationship between analytical choices and research outcomes can be visualized through the following workflow:

The decision pathway for selecting appropriate analytical approaches based on research goals can be summarized as:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Analysis

Successful microbiome research requires careful selection of reagents and computational resources. The table below outlines key components essential for robust microbiome analysis:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Reproducible Microbiome Analysis

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose | Considerations for Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | DNA extraction kits | Isolation of high-quality microbial DNA from samples | Standardized protocols minimize batch effects and technical variation [20] |

| Library preparation kits | Preparation of sequencing libraries | Validated SOPs reduce technical variability between batches [20] | |

| Mock communities | Controls for benchmarking and validation | Essential for assessing accuracy and reproducibility across runs [19] | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Kraken2/Bracken | Taxonomic classification of metagenomic data | Highest accuracy for pathogen detection in complex matrices [11] |

| QIIME2, MOTHUR, DADA2 | 16S rRNA gene analysis | Provide reproducible results when properly documented [8] | |

| MetaPhlAn4 | Taxonomic profiling | Useful alternative with moderate abundance requirements [11] | |

| Reference Databases | SILVA, Greengenes, RDP | Taxonomic classification reference | Database choice has limited impact on overall conclusions [8] |

| Custom databases | Specialized applications | Can be developed for proprietary strains [20] | |

| Computational Infrastructure | Version-controlled pipelines | Analysis reproducibility | Strict versioning guarantees consistent results [20] |

| High-performance computing | Processing large datasets | Essential for metagenomic analysis [19] |

The clinical translation of microbiome research depends critically on addressing analytical variability through standardized benchmarking and transparent reporting [15] [19]. While different bioinformatics pipelines can produce varying results, consistent biological conclusions are achievable when using robust, well-documented methods [8]. The selection of analytical tools should be guided by the specific research question, with Kraken2/Bracken demonstrating superior sensitivity for low-abundance pathogen detection [11] and platforms like QIIME2, MOTHUR, and DADA2 showing strong reproducibility for 16S rRNA-based community analyses [8].

As the field advances, embracing best practices in benchmarking—including appropriate test data selection, multiple performance metrics, and consideration of microbiome-specific data characteristics—will enhance reliability across studies [19]. The implementation of version-controlled pipelines and standardized protocols further supports reproducibility from research to clinical application [20]. Through rigorous methodology and transparent reporting, microbiome research can overcome the challenge of analytical variability and realize its full potential in clinical translation.

Benchmarked Methods and Tools: Performance Across Microbiome Analysis Tasks

Differential abundance (DA) analysis is a foundational statistical procedure in microbiome research, aiming to identify microorganisms whose abundance differs significantly between conditions, such as health versus disease. Despite its fundamental role, the field lacks consensus on optimal methodological approaches, with numerous studies reporting that different DA tools yield discordant results when applied to the same datasets [9] [21]. This inconsistency poses a significant challenge for biomarker discovery and biological interpretation, potentially undermining the reproducibility of microbiome research.

The absence of standardized benchmarking practices compounds this challenge. Earlier evaluations often relied on parametric simulations that generated data dissimilar to real experimental datasets, potentially leading to circular arguments and biased recommendations [22] [9]. Consequently, method selection often appears arbitrary, creating the possibility for cherry-picking tools that support pre-existing hypotheses. This comprehensive review synthesizes evidence from recent large-scale benchmarking studies to objectively evaluate 22 statistical methods for differential abundance testing, providing researchers with evidence-based recommendations for selecting robust DA tools across various experimental conditions.

Performance Comparison of Differential Abundance Methods

Evaluation of differential abundance methods reveals significant variation in their false discovery rate (FDR) control, sensitivity, and replicability. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for the most comprehensively evaluated methods across multiple independent benchmarks.

Table 1: Performance Overview of Differential Abundance Testing Methods

| Method Category | Method Name | FDR Control | Sensitivity | Replicability | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Statistical | Wilcoxon test | Generally robust [22] | Moderate [22] | High [23] [24] | Non-parametric; analyzes relative abundances |

| T-test | Generally robust [22] | Moderate [22] | High [23] [24] | Parametric; assumes normality | |

| Linear models | Good with covariate adjustment [22] | Moderate [22] | High [23] [24] | Flexible for complex designs | |

| RNA-Seq Adapted | DESeq2 | Variable [21] | Moderate to high [21] | Moderate [24] | Negative binomial model; robust normalization |

| edgeR | Can be inflated [9] [21] | High [9] | Moderate [24] | Negative binomial model | |

| limma-voom | Generally robust [22] | High [22] [9] | Moderate [24] | Linear models with precision weights | |

| Compositionally Aware | ANCOM/ANCOM-BC | Generally robust [22] [21] | Low to moderate [9] [21] | Moderate [9] | Addresses compositional effects specifically |

| ALDEx2 | Generally robust [9] [21] | Low to moderate [9] [21] | High [9] | Compositional data analysis (CLR transformation) | |

| ZicoSeq | Generally robust [21] | High [21] | Not fully evaluated | Designed specifically for microbiome data | |

| Other Microbiome-Specific | metagenomeSeq | Can be inflated [9] [21] | Variable [21] | Moderate [24] | Zero-inflated Gaussian model |

| MaAsLin2 | Variable [21] | Moderate [21] | Moderate [24] | Generalized linear models |

Performance Metrics and Interpretation

- False Discovery Rate Control: The ability of a method to correctly control false positives when no true differences exist. Methods with poor FDR control may identify spurious associations [22] [21].

- Sensitivity: The ability to detect true positives when abundance differences truly exist. Methods with low sensitivity may miss biologically relevant findings [22] [21].

- Replicability: The consistency of results across different datasets or study populations. Highly replicable methods produce more reliable biomarkers [23] [24].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Studies

Real Data-Based Simulation with Signal Implantation

Recent benchmarks have adopted innovative simulation approaches that implant calibrated signals into real taxonomic profiles, creating a known ground truth while preserving the complex characteristics of real microbiome data [22].

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Real Data-Based Benchmarking

| Protocol Step | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Data Selection | Use real microbiome datasets from healthy populations as baseline | Preserves natural microbial community structure and covariation |

| Signal Implantation | Multiply counts in one group with a constant factor (abundance scaling) and/or shuffle non-zero entries across groups (prevalence shift) | Creates known differentially abundant features with controlled effect sizes |

| Effect Size Calibration | Align implanted effect sizes with those observed in real disease studies (e.g., colorectal cancer, Crohn's disease) | Ensures biological relevance of simulations |

| Method Application | Apply multiple DA methods to identical simulated datasets | Enables direct comparison of performance metrics |

| Performance Evaluation | Calculate false discovery rates, sensitivity, and replicability metrics | Quantifies method performance under controlled conditions |

The key advantage of this signal implantation approach is that it "generates a clearly defined ground truth of DA features (like parametric methods) while retaining key characteristics of real data" [22]. This addresses a critical limitation of purely parametric simulations, which often produce data distinguishable from real experimental data by machine learning classifiers [22].

Large-Scale Consistency Assessment

An alternative benchmarking approach evaluates methods based on their consistency and replicability across multiple real datasets, avoiding simulation assumptions entirely [23] [24]. This protocol involves:

- Dataset Collection: Compiling numerous datasets from independent studies comparing similar conditions (e.g., healthy vs. colorectal cancer)

- Split-Half Analysis: Randomly dividing datasets into exploratory and validation halves to assess internal consistency

- Cross-Study Validation: Testing whether findings from one study replicate in independent datasets

- Conflict Measurement: Quantifying the percentage of results that show significant effects in opposite directions between validation attempts

This approach identifies methods that "produce a substantial number of conflicting findings" [23] and emphasizes result stability as a key performance metric.

Diagram 1: Differential Abundance Method Benchmarking Workflow. The flowchart illustrates the two complementary approaches for evaluating DA methods: simulation-based evaluation with known ground truth and consistency-based evaluation using real datasets.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Differential Abundance Analysis

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Frameworks | sparseDOSSA2, metaSPARSim, MIDASim | Generate synthetic microbiome data with known ground truth for method validation [25] |

| 16S rRNA Analysis Pipelines | DADA2, QIIME2, mothur | Process raw 16S sequencing data into abundance tables [21] |

| Shotgun Metagenomic Profilers | MetaPhlAn2, MetaPhlAn4, Kraken2/Bracken | Taxonomic profiling from whole metagenome sequencing data [21] [11] |

| Normalization Methods | Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS), Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM), Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) | Address compositionality and varying sequencing depth [21] |

| Benchmarking Platforms | Custom R/Python scripts using real data-based simulations | Standardized performance evaluation across multiple methods [22] |

Discussion and Recommendations

Key Findings Across Benchmarking Studies

Synthesizing evidence across multiple large-scale evaluations reveals several consistent patterns. First, classical statistical methods, including the Wilcoxon test, t-test, and linear models, demonstrate robust false discovery rate control and high replicability, though with sometimes moderate sensitivity [22] [23] [24]. Their straightforward implementation and interpretability make them suitable for initial exploratory analyses.

Second, compositionally aware methods (e.g., ANCOM-BC, ALDEx2) specifically address the compositional nature of microbiome data and generally provide good FDR control, though sometimes at the cost of reduced sensitivity [22] [21]. These methods are particularly valuable when investigating taxa that are highly abundant or suspected to be drivers of compositional variation.

Third, the performance of many methods deteriorates under confounding conditions, but this can be mitigated through appropriate experimental design and statistical adjustment. As demonstrated in a large cardiometabolic disease dataset, "failure to account for covariates such as medication causes spurious association in real-world applications" [22]. Methods that support covariate adjustment (e.g., linear models, limma, fastANCOM) maintain better performance in the presence of confounding factors.

Recommendations for Practitioners

Based on comprehensive benchmarking evidence, we recommend the following practices for differential abundance analysis:

Employ a Consensus Approach: Given that "no single method is simultaneously robust, powerful, and flexible across all settings" [21], researchers should consider applying multiple complementary methods and focusing on consistently identified taxa.

Validate with Independent Data: Whenever possible, validate findings across independent datasets or through split-half validation to assess result stability [23] [24].

Address Confounding Systematically: Include relevant covariates (medication, diet, demographics) in analytical models to reduce spurious associations [22].

Prioritize Replicability Over Novelty: Methods producing highly replicable results (e.g., Wilcoxon test, linear models, logistic regression for presence/absence data) [23] [24] generally provide more reliable biological insights than methods with unstable findings, regardless of statistical significance.

Consider Data Characteristics: Method performance depends on data properties such as sample size, effect size, sparsity, and sequencing depth. Tailor method selection to specific data characteristics and experimental questions [25].

As the field continues to evolve, ongoing methodology development and benchmarking will be essential for improving the reproducibility of microbiome association studies. The benchmarking frameworks and software tools developed in recent studies provide a foundation for continued method evaluation and refinement [22].

The rapid advancement of high-throughput sequencing technologies has enabled the generation of microbiome and metabolome data at an exponential scale, creating unprecedented opportunities for investigating complex biological systems and their roles in human health and disease [4]. The integration of these high-dimensional biological data holds great potential for elucidating the complex mechanisms underlying diverse biological systems, particularly the interactions between microorganisms and metabolites which have been linked to conditions such as cardio-metabolic diseases, autism spectrum disorders, and inflammatory bowel disease [4] [26]. However, a significant challenge persists: no standard currently exists for jointly integrating microbiome and metabolome datasets within statistical models, leaving researchers with a daunting array of analytical choices without clear guidance on their appropriate application [4].

This comprehensive review addresses this critical gap by synthesizing findings from a systematic benchmark of nineteen integrative methods for disentangling the relationships between microorganisms and metabolites [4]. Through realistic simulations and validation on real gut microbiome datasets, this benchmark identified best-performing methods across key research goals, including global associations, data summarization, individual associations, and feature selection [4]. By providing practical guidelines tailored to specific scientific questions and data types, this work establishes a foundation for research standards in metagenomics-metabolomics integration and supports the design of optimal analytical strategies for diverse research objectives.

Methodological Framework: Categories of Integrative Analysis

Integrative methods for microbiome-metabolome data can be classified into distinct categories based on the scale of associations they examine and the specific research questions they address. Consistent with recent reports, traditional workflows include four complementary types of analysis, each with distinct methodological approaches and interpretation frameworks [4].

Analytical Approaches by Research Goal

Table 1: Categories of Integrative Methods for Microbiome-Metabolome Data

| Analysis Type | Research Question | Example Methods | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Associations | Determine presence of overall association between two omic datasets | Procrustes analysis, Mantel test, MMiRKAT [4] | Initial screening to establish dataset relationships |

| Data Summarization | Identify latent structures that explain shared variance | CCA, PLS, RDA, MOFA2 [4] | Dimensionality reduction and visualization |

| Individual Associations | Detect specific microorganism-metabolite relationships | Pairwise correlation/regression, LASSO [4] | Hypothesis generation for mechanistic studies |

| Feature Selection | Identify most relevant associated features across datasets | Sparse CCA (sCCA), sparse PLS (sPLS) [4] | Biomarker discovery and validation |

Special Considerations for Microbiome and Metabolome Data

The integration of microbiome and metabolome data requires particular attention to their inherent data structures and properties. Microbiome data presents unique analytical challenges due to properties such as over-dispersion, zero inflation, high collinearity between taxa, and its compositional nature [4]. Proper handling of this compositionality is crucial for avoiding spurious results, often through transformations like centered log-ratio (CLR) or isometric log-ratio (ILR) [4]. Metabolomics, on the other hand, offers a comprehensive snapshot of the small molecules within a biological system, but similarly often exhibits over-dispersion and complex correlation structures [4].

Experimental Benchmark: Design and Evaluation Framework

Simulation Setup and Data Generation

To provide an unbiased comparison of methodological performance, the benchmark study employed sophisticated simulation approaches using the Normal to Anything (NORtA) algorithm, which allows for generating data with arbitrary marginal distributions and correlation structures [4]. This approach enabled the creation of realistic datasets with known ground truth associations, essential for proper method evaluation.

Microbiome and metabolome data were simulated based on three real microbiome-metabolome datasets with different characteristics [4]:

- Konzo dataset: High-dimensional data comprising 171 samples, 1,098 taxa, and 1,340 metabolites, with microbiome data following a negative binomial distribution and metabolome data following a Poisson distribution

- Adenomas dataset: Intermediate-size data including 240 samples, 500 taxa, and 463 metabolites, with zero-inflated negative binomial distributions for microbiome and log-normal for metabolome

- Autism spectrum disorder dataset: Small dataset consisting of 44 samples, 322 microbial taxa, and 61 metabolites, with zero-inflated negative binomial structures for microbiome and Poisson for metabolome

To estimate the marginal distributions and correlation structures used in the simulations, researchers pooled all samples from each dataset regardless of study group, without explicitly modeling group-specific effects [4]. Correlation networks for species and metabolites were estimated using SpiecEasi, and normal distributions were converted into correlated distributions matching the original data structures [4].

Method Evaluation Metrics

The benchmark evaluated methods based on multiple performance criteria tailored to each analytical category [4]:

- Global associations: Ability to detect significant overall correlations while controlling false positives

- Data summarization: Capacity to capture and explain shared variance between datasets

- Individual associations: Sensitivity and specificity for detecting meaningful pairwise specie-metabolite relationships

- Feature selection: Stability and non-redundancy in identifying the most relevant associated features across datasets

Methods were tested under three realistic scenarios with varying sample sizes, feature numbers, and data structures, with 1000 replicates per scenario to ensure statistical robustness [4]. Additional scenarios were generated for methods requiring specific assumptions, with detailed documentation provided in supplementary materials.

Benchmark Results: Performance Across Method Categories

Comparative Performance of Integrative Methods

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Method Categories

| Method Category | Strengths | Limitations | Best Performing Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Association Methods | Aggregate small effects; avoid multiple testing burden | May miss associations if only small feature subset associated; technical artifacts from data properties | MMiRKAT, Procrustes analysis with appropriate distance measures |

| Data Summarization Methods | Identify strongest covariation signals; facilitate visualization | Latent structures may lack biological interpretability; require careful normalization | MOFA2, PLS with compositional transformations |

| Individual Association Methods | Simple implementation; appropriate for hypothesis generation | Severe multiple testing burden; correlation structure must be accounted for | Appropriate transformations (CLR/ILR) followed by robust correlation measures |

| Feature Selection Methods | Address multicollinearity; identify stable, non-redundant features | Biological interpretability may remain challenging | Sparse PLS, sparse CCA with proper regularization |

The benchmark revealed that method performance significantly depended on proper data handling, particularly appropriate transformations for compositional data [4]. For microbiome data, transformations like CLR and ILR were crucial for avoiding spurious results, while for metabolomics data, log transformations often improved performance [4]. The inherent complexities of microbiome and metabolome data were found to limit the biological interpretability of results obtained from standard methods, highlighting the importance of method selection based on specific research questions [4].

Impact of Data Properties on Method Performance

The simulation studies provided valuable insights into how data characteristics influence methodological performance [4]:

- Sample size: Methods varied in their sensitivity to sample size, with some maintaining performance in smaller datasets (n=44) while others required larger sample sizes for stable results

- Data dimensionality: High-dimensional datasets (1,000+ features) posed challenges for methods without built-in regularization

- Effect size: The strength and number of true associations between microorganisms and metabolites significantly impacted detection power

- Data distribution: Methods responded differently to over-dispersed, zero-inflated, and compositional data structures

These findings underscore the importance of selecting methods aligned with dataset characteristics and research objectives rather than relying on one-size-fits-all approaches.

Experimental Protocols for Method Implementation

Standardized Workflow for Integrative Analysis

The benchmarking study revealed that a systematic approach to microbiome-metabolome integration yields more reproducible and biologically meaningful results. Based on these findings, the following experimental protocol is recommended:

Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Transformation

- Apply appropriate transformations to address compositionality of microbiome data (CLR or ILR)

- Transform metabolomics data (typically log transformation) to address over-dispersion

- Account for zero inflation through careful consideration of pseudocounts or model-based approaches

Step 2: Method Selection Based on Research Question

- For global association assessment: Implement MMiRKAT or Procrustes analysis

- For data summarization and visualization: Apply MOFA2 or PLS variants

- For individual association detection: Use appropriate transformations followed by correlation analysis with multiple testing correction

- For feature selection: Employ sparse CCA or sparse PLS with proper regularization

Step 3: Validation and Biological Interpretation

- Validate findings on independent datasets where possible

- Interpret results in context of known biological pathways and mechanisms

- Use complementary methods to triangulate evidence for key findings

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Microbiome-Metabolome Integration

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SpiecEasi | Correlation network estimation | Inferring microbial associations and creating realistic simulation structures [4] |

| NORtA algorithm | Data simulation with arbitrary distributions | Generating realistic benchmark datasets with known ground truth [4] |

| mixOmics R package | Multivariate data integration | Implementing sCCA, sPLS, and related methods [27] |

| MOFA2 | Multi-omics factor analysis | Data summarization and identifying latent factors across omics [4] |

| MetaboAnalyst | Metabolomics data analysis | Pathway analysis and visualization of metabolomics data [4] |

| QIIME 2 | Microbiome data analysis | Processing and analyzing 16S rRNA and metagenomic data [28] |

| Kraken | Taxonomic classification | Rapid classification of metagenomic sequences [28] |

Applications to Real Biological Questions

Insights from Application to Konzo Disease Dataset

When applied to real gut microbiome and metabolome data from Konzo disease, the top-performing methods revealed a complex multi-scale architecture between the two omic layers [4]. The benchmark demonstrated that different methods uncovered complementary biological processes, highlighting the value of employing multiple analytical strategies to obtain a comprehensive understanding of microbiome-metabolome interactions [4].

Similar integrative approaches have shown utility across diverse research contexts, including:

- Parkinson's disease diagnostics: Integrated analysis of tongue coating samples revealed significant alterations in microbial taxa and decreased levels of specific metabolites like palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), suggesting potential non-invasive diagnostic approaches [29]

- Cervical cancer biomarkers: Identification of key microbiota (Porphyromonas, Pseudofulvibacter) and metabolites (Cellopentaose, PGE2) as diagnostic biomarkers with high predictive value [30]

- Myocardial infarction: Discovery of three bacterial taxa (Proteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, Bacilli) and twenty metabolites as potential biomarkers, achieving exceptional diagnostic accuracy (AUC 0.99-1) [31]

- Nutritional science: Investigation of fermented soybean meal revealed its regulatory effects on gut microbiota of late gestation sows through glutathione metabolism, tyrosine metabolism, and pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis pathways [32]

Clinical Translation and Precision Medicine Applications

The integration of metabolomics and metagenomics plays an increasingly important role in clinical translation, particularly in biomarker screening, precision medicine, microbiome medicine, and drug discovery [33]. As these methods become more standardized and validated, they offer promising avenues for developing novel diagnostic approaches and therapeutic interventions based on comprehensive characterization of host-microbiome metabolic interactions [33].

This systematic benchmark of nineteen integrative strategies for microbiome-metabolome data provides much-needed guidance for researchers navigating the complex landscape of multi-omic integration. The findings demonstrate that method performance varies substantially across different research goals and data types, underscoring the importance of selective method application based on specific scientific questions rather than seeking universal solutions.

Future methodological development should focus on several key areas [4] [26]:

- Improved handling of microbiome-specific data properties in integration frameworks

- Development of more interpretable models that facilitate biological insight

- Extension of methods for longitudinal study designs and causal inference

- Creation of standardized reporting frameworks for enhanced reproducibility

- Integration of additional omic layers for more comprehensive systems biology approaches

As the field continues to evolve, the establishment of research standards based on empirical benchmarking studies will be crucial for advancing our understanding of microbiome-metabolome interactions and their roles in health and disease. The practical guidelines provided by this benchmark represent a significant step toward this goal, enabling researchers to design optimal analytical strategies tailored to their specific integration questions.

For researchers implementing these methods, a comprehensive user guide with all associated code has been provided to facilitate application in diverse contexts and promote scientific replicability and reproducibility [4]. By adopting these validated approaches and reporting standards, the research community can accelerate discoveries in microbiome-metabolome research and its translation to clinical applications.

Taxonomic profiling from metagenomic data is a fundamental step in microbiome research, with applications ranging from human health diagnostics to environmental monitoring. The selection of an appropriate bioinformatics tool is critical, as it directly impacts the accuracy and reliability of results. This guide provides an objective comparison of three widely used tools—Kraken2/Bracken, MetaPhlAn4, and Centrifuge—synthesizing evidence from recent benchmarking studies to inform researchers and drug development professionals. Performance varies significantly across different experimental scenarios, and no single tool excels in all conditions, making context-aware selection essential [34].

The following tables summarize the key performance metrics of Kraken2/Bracken, MetaPhlAn4, and Centrifuge across different testing scenarios and computational resource requirements.

Table 1: Performance metrics across different testing scenarios

| Metric / Scenario | Kraken2/Bracken | MetaPhlAn4 | Centrifuge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy (F1-Score) | Highest (0.94-0.99 in food matrices) [11] | High, but variable [11] | Lowest in food pathogen detection [11] |

| Detection Sensitivity | Best; detects down to 0.01% abundance [11] [35] | Limited at very low abundances (0.01%) [11] [35] | Higher limit of detection [11] |

| Precision | High [36] | Very high in simulated datasets [36] | Lower; generates more false positives [37] |

| Abundance Estimation | Accurate estimation [36] | Less accurate (higher L2 distance) [36] | Accurate estimation [36] |

| Speed | Fast execution [36] | Fast execution [36] | Not top performer |

| Performance with Host DNA | Affected by high host background [38] | Performance decreases with high host content [37] | Prone to false positives [37] |

| Best Use Cases | Pathogen detection, low-abundance taxa, general purpose [11] [37] | Community profiling where high precision is needed [36] [39] | Specific research needs requiring confirmation |

Table 2: Computational resource and methodological profile

| Characteristic | Kraken2/Bracken | MetaPhlAn4 | Centrifuge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification Method | k-mer based (DNA-to-DNA) [39] | Marker-gene based (DNA-to-Marker) [39] | k-mer based (DNA-to-DNA) [39] |

| Database Comprehensiveness | Comprehensive genomic sequences [40] | Clade-specific marker genes [34] | Comprehensive genomic sequences [39] |

| Computational Efficiency | Fast, low memory footprint [40] | Fast execution [36] [40] | Not the most efficient [11] |

| Relative Abundance Tool | Bracken (re-estimates abundances) [40] | Built-in profiling [34] | Integrated abundance estimation [36] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols from Benchmarking Studies

Protocol 1: Benchmarking for Foodborne Pathogen Detection

This protocol evaluates tool performance in detecting specific pathogens within complex food matrices, a scenario critical for food safety and outbreak surveillance [11] [35].

- Sample Preparation: Simulated metagenomes were constructed to represent three distinct food products: chicken meat, dried food, and milk. Defined pathogenic strains (Campylobacter jejuni, Cronobacter sakazakii, and Listeria monocytogenes) were introduced into these backgrounds at varying relative abundance levels: 0% (control), 0.01%, 0.1%, 1%, and 30% [11] [35].

- Data Analysis: Raw sequencing reads from the simulated metagenomes were processed using the default parameters for each classifier: Kraken2, Kraken2/Bracken, MetaPhlAn4, and Centrifuge [11].

- Performance Evaluation: The outputs were compared against the known ("ground truth") compositions. Key metrics included:

- F1-score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric for overall accuracy [11].

- Limit of Detection: The lowest abundance level at which a tool could consistently identify the target pathogen [11] [35].

- Abundance Estimation Accuracy: The correlation between the measured and expected abundances of the spiked pathogens [11].

Protocol 2: Benchmarking on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Metagenomes

This protocol assesses tools on real human clinical samples, where accurate species-level identification and abundance estimation are crucial for discovering microbial biomarkers of disease [36].

- Sample Preparation: Real metagenomic samples from an IBD study, including patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn's disease (CD), and control non-IBD (CN) individuals, were used. This provides a complex, real-world dataset with genuine biological variation [36].

- Data Analysis: The tools (MetaPhlAn4, Centrifuge, Kraken2, and Bracken) were run on these samples. The analysis focused on taxonomic classification at the family and species levels. For example, the abundance of Escherichia coli in the CD and UC groups compared to the CN group was examined [36].

- Performance Evaluation:

- Precision and Recall: Assessed using a simulated dataset where the true composition was known. MetaPhlAn4 showed high precision, while Kraken2 achieved the best Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) [36].

- Abundance Estimation Fidelity: Measured using the L2 norm (Euclidean distance) between the estimated and true abundance vectors. MetaPhlAn4 showed a higher L2 distance, while Centrifuge, Kraken2, and Bracken showed more accurate estimation [36].

- Interpretation Caution: The study highlighted that Bracken could overestimate the abundance of specific species like E. coli, indicating that results require careful interpretation [36].

Protocol 3: Benchmarking on Low Microbial Biomass Metatranscriptomic Samples

This protocol tests tools in challenging conditions where microbial signal is low and host genetic material dominates, such as in human tissue biopsies [37].

- Sample Preparation: Synthetic host-microbiome samples were created by spiking a mock bacterial community into human cell line RNA. Samples with varying host cell proportions (10%, 70%, 90%, and 97%) were prepared to mimic different levels of microbial biomass [37].

- Data Analysis: Total RNA was sequenced, and reads were pre-processed to remove adapter sequences, low-quality reads, and host-derived sequences. The filtered reads were then analyzed by the classifiers, with Kraken2/Bracken tested under multiple parameter settings to optimize for low biomass [37].

- Performance Evaluation:

- Recall and Precision: The number of correctly identified mock species (true positives) and the number of incorrectly identified species not in the mock (false positives) were calculated for each tool and setting [37].

- Tool Optimization: The "confidence" threshold in Kraken2 was adjusted to lower false-positive classifications, which was a critical step for improving precision in low-biomass scenarios [37].

Tool Selection Workflow and Technical Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting the most appropriate tool based on research objectives and sample characteristics, integrating findings from multiple benchmarking studies.

The technical approaches of these tools underpin their performance characteristics, as illustrated in the following architecture diagram of their classification methods.

Table 3: Key reagents and resources for metagenomic benchmarking studies

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example Use in Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Mock Communities (DMCs) | Precisely defined mixtures of known microorganisms providing "ground truth" for validation. | Zymo Biomics Gut Microbiome Standard and ATCC mock communities used for tool validation [34] [38]. |

| Synthetic Metagenomes | In silico simulated sequencing reads generated from a defined list of genomes and abundances. | Used to test pathogen detection in food matrices at specific abundance levels (e.g., 0.01% to 30%) [11] [39]. |

| Reference Databases | Curated collections of genomic sequences essential for taxonomic classification. | Kraken2, Centrifuge, and MetaPhlAn4 each require specific, often non-interchangeable, database formats [34] [40]. |

| Host Genomic Material | DNA or RNA from a host organism (e.g., human cell lines). | Used to spike synthetic samples for testing performance in low microbial biomass scenarios [37]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Integrated workflows for read pre-processing, classification, and abundance estimation. | The Kraken suite protocol encompasses classification, Bracken for abundance estimation, and KrakenTools/Pavian for analysis [40]. |

The benchmarking data consistently shows that Kraken2/Bracken offers the most robust performance for sensitive pathogen detection and accurate abundance estimation across diverse sample types, making it particularly suitable for clinical diagnostics and food safety applications. MetaPhlAn4 excels in providing high-precision community profiles but is less effective for detecting low-abundance organisms or in samples with high host contamination. Centrifuge generally underperforms relative to the other two tools in the cited studies. The optimal choice depends heavily on the specific research question, sample type, and required balance between sensitivity and precision. Researchers are encouraged to validate their chosen pipeline with mock communities relevant to their sample type to ensure reliable results.

This guide provides an objective comparison of three widely used bioinformatics pipelines—DADA2, MOTHUR, and QIIME2—for 16S rRNA microbiome data analysis. The assessment is framed within a broader thesis on benchmarking bioinformatics tools, focusing on their reproducibility, accuracy, and performance in generating microbial community compositions. Evaluation based on a recent multi-group comparative study reveals that while all three pipelines produce broadly comparable and reproducible results for core microbial findings, they exhibit differences in sensitivity for low-abundance taxa and sequence retention rates during quality control. The choice of taxonomic database also influences outcomes, though to a lesser extent than pipeline selection. This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with critical data to inform pipeline selection for robust and reproducible microbiome research.