Bayesian Frameworks for Regulon Prediction: Integrating Computational Biology and Multi-Omics Data

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Bayesian probabilistic frameworks for elucidating regulons—groups of co-regulated operons—in microbial genomes.

Bayesian Frameworks for Regulon Prediction: Integrating Computational Biology and Multi-Omics Data

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Bayesian probabilistic frameworks for elucidating regulons—groups of co-regulated operons—in microbial genomes. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational concepts of Bayesian networks and their powerful application in modeling the uncertainty inherent in transcriptional regulatory network inference. The content details cutting-edge computational methodologies, from structure learning to inference algorithms, and addresses key challenges such as data quality and model selection. Further, it examines rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses of prediction tools. By synthesizing insights from comparative genomics, transcriptomics, and multi-omics integration, this article serves as a guide for leveraging Bayesian approaches to achieve more accurate, reliable, and biologically interpretable regulon predictions, with significant implications for understanding disease mechanisms and advancing therapeutic development.

Foundations of Regulons and Bayesian Probability

In bacterial systems, a regulon is defined as a maximal set of co-regulated operons (or genes) scattered across the genome and controlled by a common transcription factor (TF) in response to specific cellular or environmental signals [1] [2]. This organizational unit represents a fundamental concept in transcriptional regulation that extends beyond the simpler operon (a cluster of co-transcribed genes under a single promoter). Unlike operons, which are physically linked genetic elements, regulons comprise dispersed transcription units that are coordinately controlled, allowing for a synchronized transcriptional response to stimuli.

The biological significance of regulons is profound. They enable organisms to mount coordinated responses to environmental changes, such as stress, nutrient availability, or other external signals [3] [2]. For example, in E. coli, the phosphate-specific (pho) regulon coordinates the expression of approximately 24 phosphate-regulated promoters in response to phosphate starvation, involving complex regulatory mechanisms including cross-talk between regulatory proteins [2]. This coordinated regulation ensures economic use of cellular resources and appropriate timing of gene expression for adaptive responses.

Bayesian Probabilistic Frameworks for Regulon Prediction

The MotEvo Framework

MotEvo represents an integrated Bayesian probabilistic approach for predicting transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) and inferring regulatory motifs from multiple alignments of phylogenetically related DNA sequences [4]. This framework incorporates several key biological features that significantly improve prediction accuracy:

- Competition among TFs: Models the competitive binding of multiple transcription factors to nearby genomic sites

- Spatial clustering of TFBS: Accounts for the tendency of TFBSs for co-regulated TFs to cluster into cis-regulatory modules

- Evolutionary conservation: Explicitly models the evolutionary conservation of TFBSs across orthologous sequences

- Gain and loss processes: Incorporates a robust model for the evolutionary gain and loss of TFBSs along a phylogeny

The Bayesian foundation of MotEvo allows it to integrate these diverse sources of information into a single, consistent probabilistic framework, addressing methodological hurdles that previously hampered such synthesis [4].

Comparative Genomics Approaches

Early computational approaches to regulon prediction leveraged comparative genomics techniques, combining three principal methods to predict coregulated sets of genes [5]:

- Conserved operons: Genes found together in operons across multiple organisms

- Protein fusions: Distinct proteins in one organism that exist as fused polypeptides in another

- Phylogenetic profiles: Genes whose homologs are consistently present or absent together across genomes

These methods generate interaction matrices that predict functional relationships between genes, which are then clustered to identify potential regulons [5]. The upstream regions of genes within predicted regulons are analyzed using motif discovery programs like AlignACE to identify shared regulatory motifs.

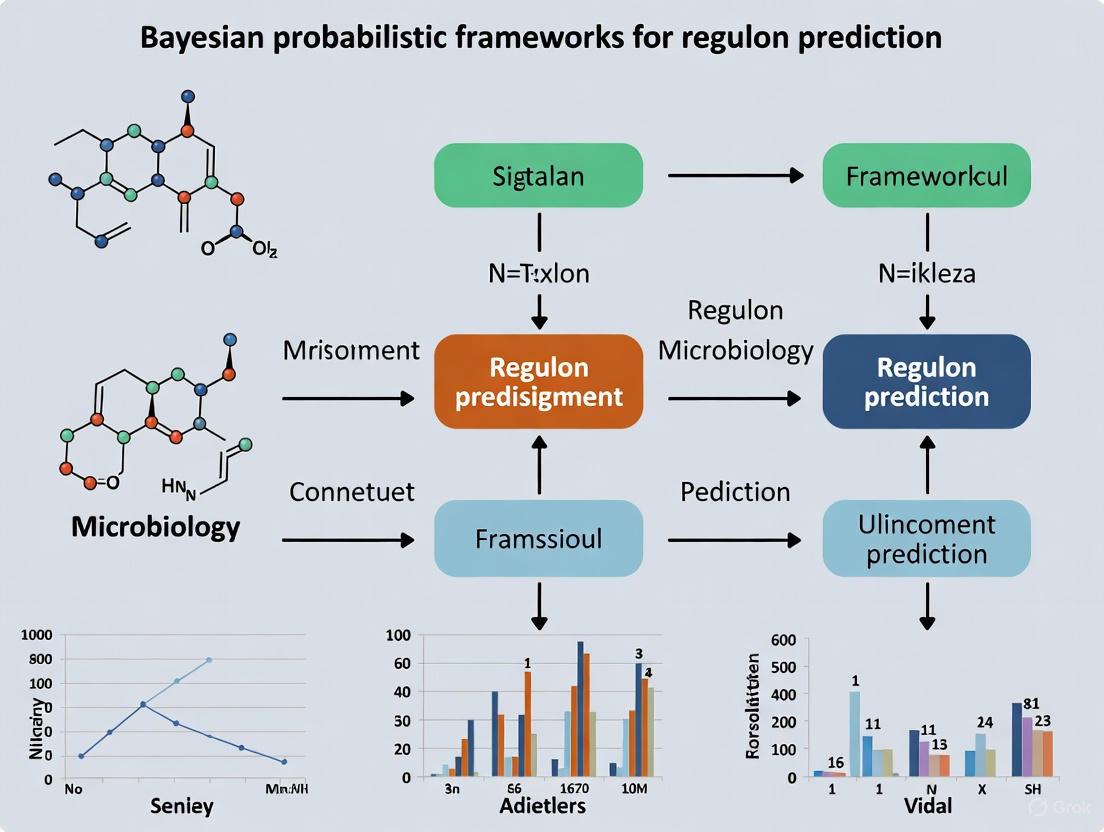

Figure 1: Bayesian framework for regulon prediction integrates multiple data types and biological constraints.

Performance and Validation

Rigorous benchmarking tests on ChIP-seq datasets have demonstrated that MotEvo's novel features significantly improve the accuracy of TFBS prediction, motif inference, and enhancer prediction compared to previous methods [4]. The integration of evolutionary information with modern Bayesian statistical approaches has proven particularly valuable in reducing false positive predictions and increasing confidence in identified regulons.

Quantitative Comparison of Regulon Prediction Methods

Table 1: Comparison of computational approaches for regulon prediction

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MotEvo | Bayesian probabilistic framework; integrates evolutionary conservation, TF competition, and spatial clustering | High accuracy on ChIP-seq benchmarks; models complex biological realities | Computational complexity; requires multiple sequence alignments |

| Comparative Genomics [5] | Combines conserved operons, protein fusions, and phylogenetic profiles | Doesn't require prior motif knowledge; uses evolutionary relationships | Limited to conserved regulons; performance depends on number of available genomes |

| CRS-based Prediction [1] | Co-regulation score between operon pairs; graph model for clustering | Effective for bacterial genomes; utilizes operon structures | Primarily developed for prokaryotes; requires reliable operon predictions |

| GRN Integration [6] | Combines cis and trans regulatory mechanisms; uses PANDA algorithm | Improved accuracy by incorporating chromatin interactions | Complex implementation; requires multiple data types |

Table 2: Key regulon databases and their characteristics

| Database | Organisms | Content | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| RegulonDB | E. coli K12 | 177 documented regulons with experimental evidence | Benchmarking computational predictions; studying network evolution |

| DOOR 2.0 | 2,072 bacterial genomes | Operon predictions including regulon information | Motif finding and regulon prediction across diverse bacteria |

| SwissRegulon | Multiple species | Computationally predicted regulatory sites | Bayesian analysis using MotEvo framework |

Experimental Protocols for Regulon Analysis

Protocol: Computational Regulon Prediction Using Integrated Bayesian Methods

Objective: To identify novel regulons in a bacterial genome using an integrated Bayesian probabilistic framework.

Materials and Reagents:

- Genomic sequence of target organism

- Orthologous genomic sequences from related organisms (for comparative analysis)

- Computing infrastructure with adequate processing power and memory

- MotEvo software suite (available from www.swissregulon.unibas.ch)

Procedure:

Data Preparation

- Obtain complete genomic sequence of target organism

- Identify orthologous operons using BLAST with E-value cutoff of 10â»âµ [5]

- Generate multiple sequence alignments of promoter regions (typically -500 to +100 bp relative to transcription start site)

Motif Identification

- Run BOBRO or similar motif finding tool on promoter sets [1]

- Parameters: search for motifs 6-20 bp in length

- Calculate conservation scores across orthologous sequences

Co-regulation Score Calculation

- Compute pair-wise co-regulation scores (CRS) between operons based on motif similarity [1]

- CRS formula incorporates motif similarity, conservation, and spatial clustering

Network Construction and Clustering

- Build regulon graph model where nodes represent operons and edges represent CRS values

- Apply hierarchical clustering algorithm to identify regulon modules

- Use evolutionary distance cutoff score of 0.1 to exclude links from closely related organisms [5]

Validation and Refinement

- Compare predictions with known regulons in databases (e.g., RegulonDB for E. coli)

- Validate using gene expression data under various conditions

- Refine regulon membership based on presence of significant regulatory motifs

Troubleshooting:

- Low number of orthologous sequences: Expand reference genome set or relax BLAST thresholds

- High false positive rate: Adjust CRS thresholds or incorporate additional validation steps

- Poor motif conservation: Consider organism-specific evolutionary rates

Protocol: Experimental Validation of Predicted Regulons

Objective: To experimentally validate computationally predicted regulons using gene expression analysis.

Materials and Reagents:

- Bacterial strain of interest

- Appropriate growth media and conditions to activate regulon

- TRIzol reagent for RNA extraction [7]

- DNase I treatment kit

- Reverse transcription reagents (oligo-dT primers, SuperScript RT-II) [7]

- PCR primers for target genes

- Microarray platform or RNA-seq capabilities

Procedure:

Condition Optimization

- Identify conditions known to activate similar regulons (e.g., stress, nutrient limitation)

- Establish time course and dose-response experiments (e.g., 0, 2, 8, 12, 16, 24, 36, 52 hours) [7]

Sample Collection and RNA Extraction

Expression Analysis

- Perform reverse transcription to generate cDNA [7]

- Conduct quantitative PCR for candidate regulon members

- Alternatively, perform microarray analysis or RNA-seq for comprehensive profiling

Data Analysis

- Identify differentially expressed genes using appropriate statistical methods (e.g., LIMMA, EBarray) [7]

- Apply multiple testing correction (Benjamini-Hochberg procedure)

- Compare expression patterns with computational predictions

Validation Criteria:

- Co-regulated genes should show similar expression patterns under inducing conditions

- Expression changes should be dose-dependent and time-dependent

- Known regulon members should cluster with predicted members

The Co-Regulation Mechanism and Biological Significance

The co-regulation mechanism, where multiple transcription factors coordinately control target genes, provides significant biological advantages that have driven its evolution:

Functional Advantages of Co-regulation

- Robustness: Highly co-regulated networks (HCNs) demonstrate greater robustness to parameter perturbation compared to little co-regulated networks (LCNs) [7]

- Biphasic Responses: Co-regulation enables biphasic dose-response patterns, allowing appropriate cellular responses across a wide range of signal intensities [7]

- Adaptability Trade-offs: While HCNs enhance robustness, they may sacrifice some adaptability to environmental changes compared to LCNs [7]

Core versus Extended Regulons

Comparative genomics analyses reveal that regulons often consist of two distinct components [2]:

- Core Regulon: Functions directly related to the primary signal sensed by the transcription factor, conserved across related species

- Extended Regulon: Functions reflecting specific ecological adaptations of a particular organism, often rapidly evolving

For example, the FnrL regulon in R. sphaeroides includes a core set of genes involved in aerobic respiration (directly related to oxygen availability) and an extended set specific to photosynthesis in this organism [2].

Figure 2: Organization of core and extended regulons shows different evolutionary patterns and functional relationships.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for regulon analysis

| Category | Item | Specification/Function | Example Sources/Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | MotEvo | Bayesian probabilistic prediction of TFBS and regulatory motifs | www.swissregulon.unibas.ch [4] |

| AlignACE | Motif discovery program for identifying regulatory motifs | Open source [5] | |

| BOBRO | Motif finding tool for phylogenetic footprinting | DMINDA server [1] | |

| PANDA | Algorithm for integrating multi-omics data into GRNs | Open source [6] | |

| Experimental Reagents | TRIzol | RNA extraction maintaining integrity for expression studies | Commercial suppliers [7] |

| DNase I | Removal of genomic DNA contamination from RNA samples | Commercial suppliers [7] | |

| SuperScript RT-II | Reverse transcription for cDNA synthesis | Commercial suppliers [7] | |

| Data Resources | RegulonDB | Curated database of E. coli transcriptional regulation | Public database [1] |

| DOOR 2.0 | Operon predictions for 2,072 bacterial genomes | Public database [1] | |

| FANTOM5 | Reference collection of mammalian enhancers | Public resource [8] | |

| Lexithromycin | Lexithromycin||For Research Use | Lexithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic for research. This product is for laboratory research use only and not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Cefalonium dihydrate | Cefalonium dihydrate, CAS:1385046-35-4, MF:C20H22N4O7S2, MW:494.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Applications in Disease and Drug Development

Understanding regulon organization and function has significant implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development:

- Disease Mechanisms: Many human disorders, including cancer, autoimmunity, neurological and developmental disorders, involve global transcriptional dysregulation [8]

- Network-Based Therapies: Regulon-level understanding enables targeting of master regulatory transcription factors rather than individual genes

- Biomarker Discovery: Transcriptome profiling of regulon activity provides potential biomarkers for disease diagnosis and monitoring [8]

The co-regulation principles observed in bacterial systems are conserved in eukaryotic systems, where complex transcriptional circuitry controls cellular differentiation, development, and disease processes. Advanced computational frameworks that integrate both cis and trans regulatory mechanisms have demonstrated improved accuracy in modeling gene expression, providing powerful approaches for understanding transcriptional dysregulation in human diseases [6].

Future Directions

The field of regulon prediction and analysis continues to evolve with several promising directions:

- Single-Cell Applications: Extending regulon analysis to single-cell transcriptomics to understand cell-to-cell heterogeneity

- Multi-Omics Integration: Combining regulon maps with epigenomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data for systems-level understanding

- Machine Learning Enhancements: Incorporating deep learning approaches to improve prediction accuracy and biological insight

- Cross-Species Conservation: Applying comparative regulonics to understand evolutionary conservation and adaptation of regulatory networks

As these methodologies advance, they will further illuminate the fundamental principles of transcriptional regulation and provide new avenues for therapeutic intervention in diseases characterized by regulatory dysfunction.

Fundamental Concepts and Theoretical Framework

A Bayesian network (BN) is a probabilistic graphical model that represents a set of variables and their conditional dependencies via a directed acyclic graph (DAG) [9]. Also known as Bayes nets, belief networks, or causal networks, they provide a compact representation of joint probability distributions by exploiting conditional independence relationships [10] [11]. Each node in the graph represents a random variable, while edges denote direct causal influences or probabilistic dependencies between variables [9] [12]. The absence of an edge between two nodes indicates conditional independence given the state of other variables in the network.

The power of Bayesian networks stems from their ability to efficiently represent complex joint probability distributions. For a set of variables ( X = {X1, X2, ..., Xn} ), the joint probability distribution can be factorized as: [ P(X1, X2, ..., Xn) = \prod{i=1}^n P(Xi | \text{pa}(Xi)) ] where ( \text{pa}(Xi) ) denotes the parent nodes of ( X_i ) in the DAG [10]. This factorization dramatically reduces the number of parameters needed to specify the full joint distribution, making computation and learning tractable even for large systems [9].

Bayesian networks combine principles from graph theory, probability theory, and computer science to create a powerful framework for reasoning under uncertainty. They support both predictive reasoning (from causes to effects) and diagnostic reasoning (from effects to causes), making them particularly valuable for biological applications where causal mechanisms must be inferred from observational data [10] [13].

Table 1: Core Components of a Bayesian Network

| Component | Description | Representation |

|---|---|---|

| Nodes | Random variables representing domain entities | Circles/ovals for continuous variables; squares for discrete variables |

| Edges | Directed links representing causal relationships or direct influences | Arrows between nodes |

| CPD/CPT | Conditional probability distribution/table quantifying relationships | Tables or functions for discrete/continuous variables |

| DAG Structure | Overall network topology without cycles | Directed acyclic graph |

Figure 1: Fundamental connection types in BNs showing serial (X→Z→A), diverging (Z→A and Z→B), and converging (A→Câ†B) patterns.

Parameter and Structure Learning Methodologies

Structure Learning Algorithms

Structure learning involves discovering the DAG that best represents the causal relationships in the data [12]. Multiple approaches exist for this task, each with different strengths and assumptions. Constraint-based algorithms like the PC algorithm use statistical tests to identify conditional independence relationships and build networks that satisfy these constraints [14]. Score-based methods assign a score to each candidate network and search for the structure that maximizes this score, using criteria such as the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) which balances model fit with complexity [14] [12]. The K2 algorithm is a popular score-based approach that uses a greedy search strategy to find high-scoring structures [14].

When implementing structure learning, the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method can be employed to search the space of possible DAGs [14]. This approach is particularly valuable when the number of variables is large, as it provides a mechanism for sampling from the posterior distribution of network structures without enumerating all possibilities. For applications with known expert knowledge, hybrid approaches that combine data-driven learning with prior structural constraints often yield the most biologically plausible networks [13].

Parameter Learning Methods

Parameter learning focuses on estimating the conditional probability distributions (CPDs) that quantify relationships between nodes [12]. For discrete variables, these are typically represented as conditional probability tables (CPTs) [10]. The simplest approach is maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), which calculates probabilities directly from observed frequencies in the data [12]. However, MLE can be problematic with limited data, as unobserved combinations receive zero probability.

Bayesian estimation methods address this limitation by incorporating prior knowledge through Dirichlet prior distributions, which are updated with observed data to obtain posterior distributions [12]. For incomplete datasets with missing values, the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm provides an iterative approach to parameter estimation that alternates between inferring missing values (E-step) and updating parameters (M-step) [9] [12].

Table 2: Bayesian Network Parameter Learning Methods

| Algorithm | Data Requirements | Basic Principle | Advantages & Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Likelihood Estimation | Complete data | Estimates parameters by maximizing the likelihood function | Fast convergence; poor performance with sparse data |

| Bayesian Estimation | Complete data | Uses prior distributions updated with observed data | Incorporates prior knowledge; computationally intensive |

| Expectation-Maximization | Incomplete data | Iteratively applies expectation and maximization steps | Effective with missing data; may converge to local optima |

| Monte Carlo Methods | Incomplete data | Uses random sampling to estimate joint probability distribution | Flexible for complex models; computationally expensive |

Experimental Protocol for Regulon Prediction

Data Preparation and Preprocessing

Objective: Prepare gene expression data and prior knowledge for Bayesian network structure learning to predict regulon structures.

Materials and Reagents:

- Gene expression dataset (RNA-seq or microarray)

- Computational resources with sufficient memory and processing power

- BN analysis software (Banjo, GeNIe, or similar)

Procedure:

Data Collection: Gather gene expression data for genes of interest under multiple conditions or time points. Include known transcription factors and their potential target genes.

Data Discretization: Convert continuous expression values into discrete states using appropriate methods:

- For normally distributed data, use z-score transformation with thresholds:

Low expression: z < -1Normal expression: -1 ≤ z ≤ 1High expression: z > 1 [13]

- For non-normal distributions, use quantile-based binning (e.g., tertiles or quartiles)

- For normally distributed data, use z-score transformation with thresholds:

Prior Knowledge Integration: Incorporate existing biological knowledge about regulatory relationships from databases such as RegulonDB or STRING using a prior probability distribution over possible network structures.

Network Structure Learning

Objective: Learn the causal structure of gene regulatory networks from processed data.

Procedure:

Algorithm Selection: Choose a structure learning algorithm appropriate for your dataset size and complexity:

- For small networks (<50 nodes): Use exhaustive search or K2 algorithm

- For medium networks (50-200 nodes): Use MCMC methods

- For large networks (>200 nodes): Use constraint-based methods like PC algorithm

Structure Search: Execute the chosen algorithm with appropriate parameters:

- For MCMC: Set chain length (typically 10,000-1,000,000 iterations), burn-in period (10-20% of chain length), and sampling frequency

- For K2: Define node ordering based on biological knowledge if available

Network Evaluation: Assess learned structures using:

- Bayesian scores (BIC, BDe, BGe) to compare different structures

- Cross-validation to evaluate predictive accuracy

- Bootstrap resampling to assess edge confidence

Parameter Learning and Model Validation

Objective: Estimate conditional probability distributions and validate the complete Bayesian network model.

Procedure:

Parameter Estimation: For the learned network structure, estimate CPTs using:

- Bayesian estimation with Dirichlet priors for small datasets

- Maximum likelihood estimation for large datasets

- Expectation-maximization for datasets with missing values

Model Validation:

- Perform predictive validation by holding out a portion of data during training and testing predictive accuracy

- Conduct sensitivity analysis to determine how robust conclusions are to parameter variations

- Compare with null models to ensure learned relationships are statistically significant

Biological Validation:

- Compare predicted regulons with known regulatory relationships in literature

- Test novel predictions experimentally using techniques like ChIP-seq or RT-qPCR

- Assess enrichment of predicted targets for known transcription factor binding motifs

Figure 2: Workflow for Bayesian network-based regulon prediction.

Inference and Prediction in Bayesian Networks

Inference Algorithms

Probabilistic inference in Bayesian networks involves calculating posterior probabilities of query variables given evidence about other variables [10] [12]. This capability allows researchers to ask "what-if" questions and make predictions even with incomplete data. Exact inference algorithms include variable elimination, which systematically sums out non-query variables, and the junction tree algorithm, which transforms the network into a tree structure for efficient propagation of probabilities [12]. The junction tree algorithm is particularly effective for sparse networks and represents the fastest exact method for many practical applications.

For complex networks where exact inference is computationally intractable, approximate inference methods provide practical alternatives. Stochastic sampling methods, including importance sampling and Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approaches, generate samples from the joint distribution to estimate probabilities [9] [12]. Loopy belief propagation applies message-passing algorithms to networks with cycles, often delivering good approximations despite theoretical limitations [12]. The choice of inference algorithm depends on network structure, available computational resources, and precision requirements.

Table 3: Bayesian Network Inference Algorithms

| Algorithm | Network Type | Complexity | Accuracy | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Elimination | Single, multi-connected | Exponential in factors | Exact | Small to medium networks |

| Junction Tree | Single, multi-connected | Exponential in clique size | Exact | Sparse networks, medical diagnosis |

| Stochastic Sampling | Single, multi-connected | Inverse to evidence probability | Approximate | Large networks, any topology |

| Loopy Belief Propagation | Single, multi-connected | Exponential in loop count | Approximate | Networks with cycles, error-correcting codes |

Causal Inference and Intervention

A distinctive advantage of Bayesian networks is their capacity to represent causal relationships and reason about interventions [9] [13]. While standard probabilistic queries describe associations (e.g., "What is the probability of high gene expression given observed TF activation?"), causal queries concern the effects of interventions (e.g., "What would be the effect on gene expression if we experimentally overexpress this transcription factor?").

The do-calculus framework developed by Pearl provides a formal methodology for distinguishing association from causation in Bayesian networks [9]. This approach enables the estimation of interventional distributions from observational data when certain conditions are met. Key concepts include the back-door criterion for identifying sets of variables that eliminate confounding when estimating causal effects [9]. In regulon prediction, this causal perspective is crucial for distinguishing direct regulatory relationships from indirect correlations and for generating testable hypotheses about transcriptional control mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Bayesian Network Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context | Implementation Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Banjo | BN structure learning | Biological network inference | Java-based, MCMC and heuristic search |

| GeNIe | Graphical network interface | Model development and reasoning | Windows platform, user-friendly interface |

| BNT (Bayes Net Toolbox) | BN inference and learning | MATLAB-based research | Extensive algorithm library |

| gRbase | Graphical models in R | Statistical analysis of networks | R package, integrates with other stats tools |

| Python pgmpy | Probabilistic graphical models | Custom algorithm development | Python library, flexible implementation |

| RegulonDB | Known regulatory interactions | Prior knowledge integration | E. coli regulon database |

| STRING | Protein-protein interactions | Network contextualization | Multi-species interaction database |

| Bromamphenicol | Bromamphenicol, CAS:17371-30-1, MF:C11H12Br2N2O5, MW:412.03 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Norvancomycin hydrochloride | Norvancomycin hydrochloride, CAS:198774-23-1, MF:C65H74Cl3N9O24, MW:1471.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Application to Regulon Prediction Research

Bayesian networks offer particular advantages for regulon prediction due to their ability to integrate heterogeneous data types, model causal relationships, and handle uncertainty inherent in biological measurements [10] [12]. In transcriptional network inference, BNs can distinguish direct regulatory interactions from indirect correlations by conditioning on potential confounders, addressing a key limitation of correlation-based approaches like clustering and co-expression networks.

Successful application of BNs to regulon prediction requires careful attention to temporal dynamics. Dynamic Bayesian Networks (DBNs) extend the framework to model time-series data, capturing how regulatory relationships evolve over time [9] [11]. In a DBN for gene expression time courses, edges represent regulatory influences between time points, enabling inference of causal temporal relationships consistent with the central dogma of molecular biology.

The integration of multi-omics data represents a particularly promising application of BNs in regulon research [12]. By incorporating chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq), transcription factor binding (ChIP-seq), and gene expression (RNA-seq) data within a unified BN framework, researchers can model the complete chain of causality from chromatin state to TF binding to transcriptional output. This integrative approach can reveal context-specific regulons and identify master regulators of transcriptional programs in development and disease.

When applying BNs to regulon prediction, several special considerations apply. Network sparsity should be encouraged through appropriate priors or penalty terms, as biological regulatory networks are typically sparse. Persistent confounding from unmeasured variables (e.g., cellular metabolic state) can be addressed through sensitivity analyses. Experimental validation of novel predicted regulatory relationships remains essential, with reporter assays, CRISPR-based perturbations, and other functional genomics approaches providing critical confirmation of computational predictions.

Regulon prediction, the process of identifying sets of genes controlled by specific transcription factors (TFs), is fundamental to understanding cellular regulation and disease mechanisms. However, this field faces significant challenges due to biological complexity, with traditional computational methods often struggling to integrate diverse data types and manage inherent uncertainties. Bayesian probabilistic frameworks have emerged as powerful tools that directly address these limitations by providing a mathematically rigorous approach for handling incomplete data and quantifying uncertainty in regulatory relationships.

The core strength of Bayesian methods lies in their ability to seamlessly incorporate prior knowledge—such as interactions from curated databases—with new experimental data to update beliefs about regulatory network structures [15]. This sequential learning capability aligns perfectly with the scientific process, allowing models to become increasingly refined as more evidence becomes available. Furthermore, Bayesian approaches naturally represent regulatory networks as probabilistic relationships rather than binary interactions, providing more biologically realistic models that reflect the stochastic nature of cellular processes. These characteristics make Bayesian frameworks particularly well-suited for tackling the dynamic and context-specific nature of gene regulatory networks across different cell types, disease states, and experimental conditions.

Technical Foundation: Core Bayesian Concepts

A Bayesian network (BN) is a probabilistic graphical model representing a set of variables and their conditional dependencies via a directed acyclic graph (DAG) [12]. In the context of regulon prediction, nodes typically represent biological entities such as transcription factors, target genes, or proteins, while edges represent regulatory relationships or causal influences. Each node is associated with a conditional probability table (CPT) that quantifies the likelihood of its states given the states of its parent nodes.

The implementation of Bayesian networks for regulon prediction primarily focuses on three technical aspects: structure learning, parameter learning, and probabilistic inference. Structure learning involves constructing the DAG to represent relationships between variables by identifying dependency and independence among variables based on data. Parameter learning involves estimating the CPTs that define the relationships between nodes in the network. Probabilistic inference enables calculation of the probabilities of unobserved variables (e.g., transcription factor activity) given observed evidence (e.g., gene expression data), making BNs powerful tools for prediction and decision support [12].

Table 1: Bayesian Network Parameter Learning Methods

| Algorithm | For Incomplete Datasets | Basic Principle | Advantages & Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Likelihood Estimate | No | Estimates parameters by maximizing the likelihood function based on observed data | Fast convergence; no prior knowledge used [12] |

| Bayesian Method | No | Uses a prior distribution and updates it with observed data to obtain a posterior distribution | Incorporates prior knowledge; computationally intensive [12] |

| Expectation-Maximization | Yes | Estimates parameters by iteratively applying expectation and maximization steps to handle missing data | Effective with missing data; can converge to local optima [12] |

| Monte-Carlo Method | Yes | Uses random sampling to estimate the expectation of the joint probability distribution | Flexible for complex models; computationally expensive [12] |

Bayesian reasoning aligns naturally with biological investigation and clinical practice [16]. The process begins with establishing a prior probability—the initial belief about regulatory relationships before collecting new data. As experimental evidence accumulates, this prior is updated to form a posterior probability that incorporates both existing knowledge and new observations. This framework enables researchers to make probabilistic statements about regulatory mechanisms that are compatible with all available evidence, moving beyond simplistic binary classifications toward more nuanced models that reflect biological reality.

Protocol: Bayesian Regulon Prediction with TIGER

Background and Principle

The TIGER (Transcriptional Inference using Gene Expression and Regulatory data) algorithm represents an advanced Bayesian approach for regulon prediction that jointly infers context-specific regulatory networks and corresponding TF activity levels [15]. Unlike methods that rely on static interaction databases, TIGER adaptively incorporates information on consensus target genes and their mode of regulation (activation or inhibition) through a Bayesian framework that can judiciously incorporate network sparsity and edge sign constraints by applying tailored prior distributions.

The fundamental principle behind TIGER is matrix factorization, where an observed log-transformed normalized gene expression matrix (X) is decomposed into a product of two matrices: (W) (regulatory network) and (Z) (TF activity matrix). TIGER implements a Bayesian framework to update prior knowledge and constraints using gene expression data, employing a sparse prior to filter out context-irrelevant edges and allowing unconstrained edges to have their signs learned directly from data [15].

Materials and Equipment

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Description | Example Sources/Formats |

|---|---|---|

| High-Confidence Prior Network | Provides initial regulatory interactions with modes of regulation | DoRothEA database, yeast ChIP data [15] |

| Gene Expression Data | Input data for network inference and TF activity estimation | RNA-seq (bulk or single-cell), microarray data [15] |

| TF Knock-Out Validation Data | Gold standard for algorithm validation | Publicly available TFKO datasets [15] |

| Bayesian Analysis Software | Tools for implementing Bayesian networks and inference | R packages, Python libraries, specialized BN tools [12] |

Computational Requirements

- Programming Environment: R (≥4.0.0) or Python (≥3.8)

- Key Libraries/Packages: decoupleR, TIGER implementation, VIPER, Inferelator

- Memory: ≥16GB RAM for moderate-sized networks (≥1000 genes, ≥100 TFs)

- Storage: ≥100GB free space for large-scale expression datasets and network files

Experimental Procedure

Step 1: Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Obtain Prior Regulatory Network: Download a high-confidence consensus regulatory network from a curated database such as DoRothEA [15]. For organism-specific studies, use specialized resources (e.g., yeast ChIP data for S. cerevisiae studies).

- Preprocess Gene Expression Data:

- Normalize raw count data using appropriate methods (e.g., TPM for bulk RNA-seq, SCTransform for single-cell RNA-seq)

- Log-transform normalized counts ((X = log2(counts + 1)))

- Filter lowly expressed genes (e.g., requiring >10 counts in ≥10% of samples)

- Align Prior Network with Expression Data: Retain only those regulatory interactions where both TF and target gene are present in the expression dataset.

Step 2: Edge Sign Constraint Assignment

- Calculate Partial Correlations: Compute partial correlations between TFs and their target genes in the gene expression input data.

- Compare with Prior Knowledge: Compare the correlation signs with the edge signs from the prior network.

- Assign Constraint Types:

- Hard Constraints: Apply when prior network signs and partial correlation signs agree

- Soft Constraints: Apply when signs disagree or prior knowledge is uncertain

- No Constraints: For edges with unknown direction in prior knowledge

Step 3: Model Initialization and Parameter Setting

- Initialize Matrices:

- Initialize (W) matrix using prior network (known interactions receive higher initial weights)

- Initialize (Z) matrix with random non-negative values

- Set Algorithm Parameters:

- Sparsity constraint parameters (λ): Controls network density

- Convergence tolerance (ε): Typically 1e-6

- Maximum iterations: Typically 1000-5000

Step 4: Model Fitting and Inference

- Execute TIGER Algorithm: Implement the Variational Bayesian method to estimate (W) and (Z) [15]

- Monitor Convergence: Track reconstruction error ((||X - WZ||^2)) across iterations

- Validate Stability: Run multiple random initializations to ensure consistent results

Step 5: Result Extraction and Interpretation

- Extract Regulatory Network: The final (W) matrix represents the context-specific regulatory network

- Extract TF Activities: The final (Z) matrix represents estimated TF activities across samples

- Identify Key Regulators: Rank TFs by variance or magnitude of activity across conditions

Troubleshooting and Optimization

- Poor Convergence: Increase maximum iterations; adjust learning rate; check for data normalization issues

- Overly Dense Network: Increase sparsity constraint parameters; strengthen prior weight

- Unbiological Results: Verify prior network quality; check for batch effects in expression data

- Computational Limitations: Implement feature selection to reduce gene set; use high-performance computing resources

Figure 1: TIGER Experimental Workflow. The diagram illustrates the sequential steps for implementing the Bayesian regulon prediction protocol.

Validation and Performance Assessment

Validation Methodologies

Rigorous validation is essential for establishing the biological relevance of predicted regulons. Multiple complementary approaches should be employed:

TF Knock-Out Validation: Utilize transcriptomic data from TF knock-out experiments as gold standards [15]. A successfully validated prediction should show the knocked-out TF having the lowest predicted activity in the corresponding sample. Calculate performance metrics including precision, recall, and area under the precision-recall curve.

Independent Functional Evidence: Compare predicted regulons with independent data not used in model training:

- ChIP-seq binding data from sources like Cistrome DB [15]

- TF overexpression transcriptomic profiles

- CRISPR screening results

Cell-Type Specificity Assessment: Apply the algorithm to tissue- and cell-type-specific RNA-seq data and verify that predicted TF activities align with known biology [15]. For example, analysis of normal breast tissue should identify known mammary gland regulators.

Performance Benchmarking

Comparative analysis against alternative methods is crucial for objective evaluation. Benchmark TIGER against established approaches including:

- VIPER: Uses differential expression in regulon genes to infer TF activity [15]

- Inferelator: Employs linear regression followed by network updating [15]

- CMF: Constrained matrix factorization with fixed regulatory interactions [15]

- decoupleR implementations: MLM, ULM, WSUM, GSVA, WMEAN, AUCELL [15]

Table 3: Bayesian Network Inference Methods for Regulon Analysis

| Algorithm | Network Type | Complexity | Accuracy | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Elimination | Single, multi-connected networks | Exponential in variables | Exact | Small networks, simple inference [12] |

| Junction Tree | Single, multi-connected networks | Exponential in largest clique | Exact | Fastest for sparse networks [12] |

| Stochastic Sampling | Single, multi-connected networks | Inverse to evidence probability | Approximate | Large networks, approximate results [12] |

| Loopy Belief Propagation | Single, multi-connected networks | Exponential in network loops | Approximate | Well-performing when convergent [12] |

Evaluation metrics should focus on the algorithm's ability to correctly identify perturbed TFs in knock-out experiments and to produce biologically plausible regulons that show enrichment for known functions and pathways.

Applications in Drug Development and Systems Medicine

Bayesian regulon prediction enables probabilistic assessment of master regulators in disease states, providing a quantitative foundation for target identification and validation in drug development. By estimating transcription factor activities rather than merely measuring their expression levels, these methods can identify key drivers of pathological processes that might not be apparent through conventional differential expression analysis.

The application of Bayesian optimal experimental design (BOED) further enhances drug discovery workflows by recommending informative experiments to reduce uncertainty in model predictions [17]. In practice, this involves:

- Defining Prior Distributions: Establish beliefs regarding model parameter distributions before data collection

- Generating Synthetic Data: Simulate experimental outcomes for each prospective measurable species

- Conducting Parameter Estimation: Perform Bayesian inference using models and simulated data

- Computing Drug Performance: Predict therapeutic outcomes using posterior distributions

- Ranking Experiments: Prioritize measurements that maximize confidence in key predictions

This approach is particularly valuable for prioritizing laboratory experiments when resources are limited, as it provides a quantitative framework for identifying which measurements will most efficiently reduce uncertainty in model predictions relevant to therapeutic efficacy [17].

Figure 2: Drug Discovery Application Pipeline. Bayesian regulon prediction informs target identification and validation in therapeutic development.

Software Tools for Bayesian Regulon Analysis

Several software tools facilitate the implementation of Bayesian networks for regulon prediction, making these methods accessible to researchers without extensive computational expertise:

Table 4: Bayesian Network Software Tools

| Tool | Language | Description | Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| BNLearn | R | Comprehensive environment for BN learning and inference | General Bayesian network analysis [12] |

| pgmpy | Python | Library for probabilistic graphical models | Flexible implementation of custom networks [12] |

| JASP | GUI | Graphical interface with Bayesian capabilities | Users preferring point-and-click interfaces [12] |

| Stan | Multiple | Probabilistic programming language | Complex custom Bayesian models [12] |

Advanced Implementation Considerations

For large-scale regulon prediction projects, several technical considerations ensure robust results:

Handling Missing Data: Implement appropriate strategies for incomplete datasets:

Computational Optimization:

Model Selection and Evaluation:

- Use Bayesian information criterion for model comparison

- Implement cross-validation strategies to assess generalizability

- Employ posterior predictive checks to verify model fit

The integration of Bayesian regulon prediction into drug development pipelines represents a paradigm shift toward more quantitative, uncertainty-aware approaches to target identification and validation. By explicitly modeling uncertainty and systematically incorporating prior knowledge, these methods provide a robust foundation for decision-making in therapeutic development.

Bayesian networks (BNs) are powerful probabilistic graphical models that represent a set of variables and their conditional dependencies via a directed acyclic graph (DAG) [9]. They provide a framework for reasoning under uncertainty and are composed of two core elements: a qualitative structure and quantitative parameters. Within the context of regulon prediction research—aimed at elucidating complex gene regulatory networks—BNs offer a principled approach for modeling the causal relationships between transcription factors, their target genes, and environmental stimuli. This document outlines the three fundamental pillars of working with Bayesian networks: structure learning, parameter learning, and probabilistic inference, providing detailed application notes and protocols tailored for research scientists in systems biology and drug development.

Core Component 1: Structure Learning

Structure learning involves identifying the optimal DAG that represents the conditional independence relationships among a set of variables from observational data [18] [19]. This is a critical first step in model construction, especially when the true regulatory network is unknown.

Algorithmic Approaches

The main algorithmic approaches for structure learning are categorized into constraint-based, score-based, and hybrid methods [18].

- Constraint-based algorithms (e.g., PC-Stable, Grow-Shrink) rely on statistical conditional independence (CI) tests to prune edges from a fully connected graph. They are grounded in the theory of causal graphical models but can be sensitive to individual test errors [18].

- Score-based algorithms (e.g., Greedy Search, FGES) define a scoring function that measures how well a graph fits the data. The learning task becomes a search problem for the structure that maximizes this score, often using heuristics like hill-climbing [18] [19] [20]. Common scores include the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), a penalized likelihood score [19], and the Bayesian Dirichlet (BD) score, a fully Bayesian marginal likelihood [19].

- Hybrid algorithms combine both approaches, typically using constraint-based methods to reduce the search space before a score-based optimization [18].

Table 1: Summary of Key Structure Learning Algorithms

| Algorithm Type | Example Algorithms | Key Mechanism | Data Requirements | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constraint-based | PC-Stable, Grow-Shrink (GS) | Conditional Independence Tests | Data suitable for CI tests (e.g., discrete for chi-square) | Sensitive to CI test choice and sample size; can be computationally efficient [18]. |

| Score-based | Greedy Search, FGES, Hill-Climber | Optimization of a scoring function (BIC, BDeu) | Depends on scoring function; handles discrete, continuous, or mixed data [18] [20]. | Search can get stuck in local optima; scoring is computationally intensive [18] [19]. |

| Hybrid | MMHC | Constraint-based pruning followed by score-based search | Combines requirements of both approaches. | Aims to balance efficiency and accuracy [18]. |

| Specialized | Chow-Liu Algorithm | Mutual information & maximum spanning tree | Discrete or continuous data for MI calculation. | Recovers the optimal tree structure; computationally efficient (O(n²)) but limited to tree structures [19]. |

Experimental Protocol for Network Structure Learning in Regulon Prediction

Objective: To reconstruct a gene regulatory network from high-throughput transcriptomics data (e.g., RNA-seq) using a score-based structure learning algorithm.

Materials:

- Data: A matrix of gene expression counts (rows: samples, columns: genes, including transcription factors and potential targets).

- Software: The

abnR package or thebnlearnR library, which offer multiple score-based and constraint-based algorithms [18] [20].

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize raw count data (e.g., using DESeq2 or edgeR). Discretize continuous expression values if required by the chosen algorithm or scoring function, though Gaussian BNs can handle continuous data directly [18].

- Score Cache Construction: Use the

buildScoreCache()function inabnto precompute the local score for every possible child-parent configuration. This dramatically speeds up the subsequent search [20]. - Structure Search: Execute a search algorithm over the space of DAGs.

- Example using

searchHillClimber()inabn: This function starts from an initial graph (e.g., empty) and iteratively adds, removes, or reverses arcs, each time adopting the change that leads to the greatest improvement in the network score until no further improvement is possible [20].

- Example using

- Model Evaluation: Assess the learned network using cross-validation or by calculating the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to balance model fit and complexity, guarding against overfitting [19].

- Incorporation of Prior Knowledge (Optional): Specify known required or forbidden edges based on existing literature (e.g., ChIP-seq confirmed TF-DNA binding) to constrain the search space and improve biological plausibility [18].

Diagram 1: Structure learning workflow.

Core Component 2: Parameter Learning

Once the DAG structure is established, parameter learning involves estimating the Conditional Probability Distributions (CPDs) for each node, which quantify the probabilistic relationships with its parents [18] [9].

Methodologies and Considerations

The two primary methodologies for parameter learning are:

- Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE): Finds the parameter values that maximize the likelihood of the observed data. MLE is straightforward but can overfit the data, especially with limited samples.

- Bayesian Estimation: Treats the parameters as random variables with prior distributions (e.g., a Dirichlet prior for discrete variables). The parameters are estimated by computing their posterior distribution given the data. This approach naturally incorporates prior knowledge and regularizes the estimates, reducing overfitting [9].

The form of the CPD depends on the data type. For discrete variables (common in regulon models where a gene is "on" or "off"), multinomial distributions are represented in Conditional Probability Tables (CPTs). For continuous variables, linear Gaussian distributions are often used [18].

Table 2: Parameter Learning Methods for Different Data Types

| Data Type | Learning Method | CPD Form | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discrete/Multinomial | Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) | Conditional Probability Table (CPT) | Simple, no prior assumptions needed. | Prone to overfitting with sparse data [9]. |

| Discrete/Multinomial | Bayesian Estimation (e.g., with Dirichlet prior) | Conditional Probability Table (CPT) | Incorporates prior knowledge, robust to overfitting. | Choice of prior can influence results [9]. |

| Continuous | Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) | Linear Gaussian | Mathematically tractable, efficient. | Assumes linear relationships and Gaussian noise [18]. |

Experimental Protocol for Learning Conditional Probability Tables

Objective: To estimate the CPTs for a fixed network structure learned in Section 2.2, using transcriptomics data discretized into "high" and "low" expression states.

Materials:

- Data: Discretized gene expression matrix.

- Structure: The learned DAG structure in a format compatible with BN software (e.g., a

bnobject inbnlearn).

Procedure:

- Structure Import: Load the learned DAG structure into the BN learning environment.

- Data Alignment: Ensure the columns of the discretized data matrix exactly match the node names in the DAG.

- Parameter Estimation: Use the

bn.fit()function in thebnlearnR package to fit the parameters of the network.- For discrete data, specify the method as "bayes" or "mle". The "bayes" method (Bayesian estimation) is generally preferred for its smoothing effect, which is crucial when some parent configurations have few or no observed samples [9].

- The function will compute a CPT for each node. For example, the CPT for a target gene

Gwith parentsTF1andTF2will contain the probabilityP(G = high | TF1=high, TF2=low)and all other parent configurations.

- Validation: Perform a predictive check by holding out a portion of the data during learning and evaluating the model's ability to predict the states of held-out variables.

Core Component 3: Probabilistic Inference

Probabilistic inference is the process of computing the posterior probability distribution of a subset of variables given that some other variables have been observed (evidence) [9] [21]. In a regulon context, this allows for querying the network to make predictions about gene states.

Inference Tasks and Algorithms

The primary task is to update belief about unknown variables given new evidence. For instance, observing the overexpression of specific transcription factors can be used to infer the probable activity states of their downstream targets, even if those targets were not measured [21].

Exact inference methods include:

- Variable Elimination: Eliminates non-query, non-evidence variables by summing them out in a specific order.

- Clique Tree Propagation: Compiles the BN into a tree of cliques for efficient, multiple queries.

With complex networks, exact inference can become computationally intractable (exponential in the network's treewidth). In such cases, approximate inference methods are used, such as:

- Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Sampling: Generates samples from the posterior distribution to approximate probabilities [22].

- Loopy Belief Propagation: Passes messages between nodes until convergence, even in graphs with cycles.

Experimental Protocol for Querying a Regulon Network

Objective: To use the fitted BN to predict the probability of downstream target gene activation given observed expression levels of a set of transcription factors.

Materials:

- A fully specified BN (structure and parameters).

- A dataset with observed values for a subset of variables (the evidence).

Procedure:

- Model Loading: Load the fully learned BN (from Sections 2.2 and 3.2) into an inference engine, such as the

bnlearnpackage. - Set Evidence: Specify the observed states of certain nodes (e.g., set

TF1 = high,TF2 = low). - Perform Inference: Execute an inference algorithm to compute the posterior distribution of the query variables.

- Example using

cpquery()inbnlearn: This function uses likelihood weighting, an approximate inference algorithm, to estimate conditional probabilities. The commandcpquery(fitted = bn_model, event = (TargetGene == "high"), evidence = (TF1 == "high" & TF2 == "low"))would return the estimated probabilityP(TargetGene = high | TF1=high, TF2=low).

- Example using

- Interpret Results: The output is a probability value that can be used to prioritize candidate genes for experimental validation. A high posterior probability suggests a strong regulatory relationship under the given conditions.

Diagram 2: Probabilistic inference process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for BN-Based Regulon Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Transcriptomics Data | Provides the observational data for learning network structure and parameters. | RNA-sequencing data from perturbation experiments (knockdown, overexpression) is highly valuable for causal discovery [18]. |

| ChIP-seq Data | Provides prior knowledge for structure learning by identifying physical TF-DNA binding. | Used to define required edges or to validate predicted regulatory links in the learned network [18]. |

| BN Structure Learning Software | Implements algorithms for reconstructing the network DAG from data. | R packages: bnlearn [18], abn [20]. Python package: gCastle [18]. |

| Parameter Learning & Inference Engine | Fits CPDs to a fixed structure and performs probabilistic queries. | Integrated into bnlearn and gCastle. |

| Discretization Tool | Converts continuous gene expression measurements to discrete states for multinomial BNs. | R functions like cut or discretize in bnlearn. |

| Computational Resources | Hardware for running computationally intensive learning algorithms. | Structure learning can be demanding; high-performance computing (HPC) clusters may be necessary for large networks (>1000 genes) [19]. |

| DPPC-d4 | DPPC-d4 (CAS 326495-33-4)|Deuterated Phospholipid | |

| Malonomicin | Malonomicin, CAS:38249-71-7, MF:C13H18N4O9, MW:374.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Topics in Bayesian Networks

Dynamic Bayesian Networks (DBNs)

DBNs extend standard BNs to model temporal processes, making them ideal for time-course gene expression data. They can capture feedback loops and delayed regulatory effects, which are common in biology but cannot be represented in a static DAG [9].

Handling Model Uncertainty with Multimodel Inference

It is often the case that multiple network structures are equally plausible given the data. Bayesian multimodel inference (MMI), such as Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA), addresses this model uncertainty by combining predictions from multiple high-scoring networks, weighted by their posterior probability [23]. This leads to more robust and reliable predictions, which is crucial for making high-stakes decisions in drug development.

Instance-Specific Learning

Traditional BNs model population-wide relationships. Instance-specific structure learning methods, however, aim to learn a network tailored to a particular sample (e.g., a single patient's tumor). This personalized approach can reveal unique causal mechanisms operative in that specific instance, with significant potential for personalized medicine [24].

Bayesian networks provide a mathematically rigorous and intuitive framework for modeling gene regulatory networks. By systematically applying structure learning, parameter learning, and probabilistic inference, researchers can move beyond correlation to uncover causal hypotheses about regulon organization and function. The protocols and tools outlined here provide a foundation for applying these powerful methods to advance systems biology and therapeutic discovery.

The accurate prediction of regulons, defined as the complete set of genes under control of a single transcription factor, represents a fundamental challenge in computational biology. The evolution of computational methods for this task mirrors broader trends in bioinformatics, transitioning from simple correlation-based approaches to sophisticated probabilistic frameworks that capture the complex nature of gene regulatory systems. This evolution has been driven by the increasing availability of high-throughput transcriptomic data and advancements in computational methodologies, particularly in the realm of Bayesian statistics and machine learning. These developments have enabled researchers to move beyond mere association studies toward causal inference of regulatory relationships, with significant implications for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets.

Early regulon prediction methods primarily relied on statistical techniques such as mutual information and correlation metrics to infer regulatory relationships from gene expression data. While these methods provided initial insights, they often struggled with false positives and an inability to distinguish direct from indirect regulatory interactions. The integration of Bayesian probabilistic frameworks has addressed many of these limitations by explicitly modeling uncertainty, incorporating prior biological knowledge, and providing a principled approach for integrating heterogeneous data types. This methodological shift has dramatically improved the accuracy and biological interpretability of computational regulon predictions.

Historical Progression of Prediction Methods

The development of computational regulon prediction strategies has followed a trajectory from simple statistical associations to increasingly sophisticated network inference techniques. Early approaches (2000-2010) predominantly utilized information-theoretic measures and correlation networks, which although computationally efficient, often failed to capture the directional and context-specific nature of regulatory interactions. Methods such as ARACNE (Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks) and CLR (Context Likelihood of Relatedness) employed mutual information to identify potential regulatory relationships, but their inability to infer directionality limited their utility for establishing true regulator-target relationships [25].

The middle period (2010-2020) witnessed the adoption of more advanced machine learning techniques, including random forests and support vector machines. GENIE3, a tree-based method, represented a significant advancement by framing regulon prediction as a feature selection problem where each gene's expression is predicted as a function of all potential transcription factors [25]. During this period, the first Bayesian approaches began to emerge, offering a principled framework for incorporating prior biological knowledge and quantifying uncertainty in network inferences. These methods demonstrated improved performance but often required substantial computational resources and carefully specified prior distributions.

The current era (2020-present) is characterized by the integration of deep learning architectures with probabilistic modeling, enabling the capture of non-linear relationships and complex regulatory logic. Hybrid models that combine convolutional neural networks with traditional machine learning have demonstrated remarkable performance, achieving over 95% accuracy in holdout tests for predicting transcription factor-target relationships in plant systems [25]. Contemporary Bayesian methods have similarly advanced, now capable of leveraging large-scale genomic datasets and sophisticated evolutionary models to infer selective constraints on regulatory elements with unprecedented resolution [26].

Table 1: Historical Evolution of Computational Regulon Prediction Methods

| Time Period | Representative Methods | Core Methodology | Key Advancements | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-2010 | ARACNE, CLR | Mutual information, correlation networks | Efficient handling of large datasets; foundation for network inference | Unable to determine directionality; high false positive rate |

| 2010-2020 | GENIE3, TIGRESS | Tree-based methods, linear regression | Improved accuracy; integration of limited prior knowledge | Limited modeling of non-linear relationships; minimal uncertainty quantification |

| 2020-Present | Hybrid CNN-ML, GeneBayes, GGRN | Deep learning, Bayesian inference, hybrid models | High accuracy (>95%); uncertainty quantification; integration of diverse data types | Computational intensity; complexity of implementation; data requirements |

Contemporary Bayesian Frameworks

GeneBayes for Selective Constraint Inference

The GeneBayes framework represents a cutting-edge Bayesian approach for estimating selective constraint on genes, providing crucial insights into regulon organization and evolution. This method combines a population genetics model with machine learning on gene features to infer an interpretable constraint metric called shet [26]. Unlike previous metrics that were severely underpowered for detecting constraints in shorter genes, GeneBayes provides accurate inference regardless of gene length, preventing important pathogenic mutations from being overlooked.

The statistical foundation of GeneBayes integrates a discrete-time Wright-Fisher model with a sophisticated Bayesian inference engine. This implementation, available through the fastDTWF library, enables scalable computation of likelihoods for large genomic datasets [26]. The framework employs a modified version of NGBoost for probabilistic prediction, allowing it to capture complex relationships between gene features and selective constraint while fully accounting for uncertainty in the estimates. This approach has demonstrated superior performance for prioritizing genes important for cell essentiality and human disease, particularly for shorter genes that were previously problematic for existing metrics.

GGRN and PEREGGRN for Expression Forecasting

The Grammar of Gene Regulatory Networks (GGRN) framework and its associated benchmarking platform PEREGGRN represent a comprehensive Bayesian approach for predicting gene expression responses to perturbations [27]. This system uses supervised machine learning to forecast expression of each gene based on the expression of candidate regulators, employing a flexible architecture that can incorporate diverse regression methods including Bayesian linear models.

A key innovation of the GGRN framework is its handling of interventional data: samples where a gene is directly perturbed are omitted when training models to predict that gene's expression, preventing trivial predictions and forcing the model to learn underlying regulatory mechanisms [27]. The platform can train models under either a steady-state assumption or predict expression changes relative to control conditions, with the Bayesian framework providing natural uncertainty estimates for both scenarios. The accompanying PEREGGRN benchmarking system includes 11 quality-controlled perturbation transcriptomics datasets and configurable evaluation metrics, enabling rigorous assessment of prediction performance on unseen genetic interventions [27].

Table 2: Contemporary Bayesian Frameworks for Regulon Analysis

| Framework | Primary Application | Key Features | Data Requirements | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GeneBayes | Inference of selective constraint | Evolutionary model; gene feature integration; shet metric | Population genomic data; gene annotations | Python/R; available on GitHub |

| GGRN/PEREGGRN | Expression forecasting | Modular architecture; multiple regression methods; perturbation handling | Transcriptomic perturbation data; regulatory network prior | Containerized implementation |

| PRnet | Chemical perturbation response | Deep generative model; SMILES encoding; novel compound generalization | Bulk and single-cell HTS; compound structures | PyTorch; RDKit integration |

PRnet for Chemical Perturbation Modeling

PRnet represents the convergence of deep learning and Bayesian methodology in a perturbation-conditioned deep generative model for predicting transcriptional responses to novel chemical perturbations [28]. This framework formulates transcriptional response prediction as a distribution generation problem conditioned on perturbations, employing a three-component architecture consisting of Perturb-adapter, Perturb-encoder, and Perturb-decoder modules.

The Bayesian elements of PRnet are manifested in its treatment of uncertainty throughout the prediction pipeline. The model estimates the full distribution of transcriptional responses ( \mathcal{N}(xi | \mui, \sigma_i^2) ) rather than point estimates, allowing for comprehensive uncertainty quantification [28]. The Perturb-adapter encodes chemical structures represented as SMILES strings into a latent embedding, enabling generalization to novel compounds without prior experimental data. This approach has demonstrated remarkable performance in predicting responses across novel compounds, pathways, and cell lines, successfully identifying experimentally validated compound candidates against small cell lung cancer and colorectal cancer.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Gene Regulatory Network Inference Using Hybrid CNN-ML

Purpose: To reconstruct genome-scale gene regulatory networks by integrating convolutional neural networks with machine learning classifiers.

Reagents and Materials:

- Biological Samples: RNA-seq data from target organism (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana, poplar, maize)

- Software Tools: Trimmomatic (v0.38), FastQC, STAR aligner (2.7.3a), CoverageBed, edgeR

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing cluster with GPU acceleration

- Reference Data: Experimentally validated TF-target pairs for training and evaluation

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Retrieve RNA-seq datasets in FASTQ format from public repositories (e.g., NCBI SRA)

- Remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases using Trimmomatic

- Assess read quality using FastQC before and after trimming

- Align trimmed reads to the reference genome using STAR aligner

- Quantify gene-level raw read counts using CoverageBed

- Normalize counts using the weighted trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) method in edgeR

Feature Engineering

- Compile known TF-target interactions from validated databases

- Generate negative examples by randomly pairing TFs and genes without evidence of interaction

- Partition data into training (80%), validation (10%), and test sets (10%), ensuring no overlap between sets

Model Training and Evaluation

- Implement CNN architecture for feature extraction from expression patterns

- Train machine learning classifiers (e.g., random forest, SVM) on extracted features

- Optimize hyperparameters using validation set performance

- Evaluate final model on held-out test set using precision-recall metrics and ROC analysis

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For limited training data, employ transfer learning from related species

- Address class imbalance through appropriate sampling strategies or loss functions

- Validate critical predictions using orthogonal experimental approaches [25]

Protocol 2: Bayesian Inference of Selective Constraint with GeneBayes

Purpose: To estimate gene-level selective constraint using a Bayesian framework integrating population genetics and gene features.

Reagents and Materials:

- Genomic Data: Population frequency spectra for loss-of-function variants

- Gene Annotations: CpG methylation levels, exome sequencing coverage, mappability metrics

- Software: GeneBayes implementation, fastDTWF (v0.0.3), modified NGBoost (v0.3.12)

- Reference Data: ClinVar variants, essential gene sets, disease association data

Procedure:

- Data Preparation

- Compile loss-of-function variant frequencies from population-scale sequencing studies (e.g., gnomAD)

- Annotate genes with features including length, expression breadth, and epigenetic marks

- Process methylation data from CpG sites and exome sequencing coverage metrics

- Curate training labels from essential gene databases and disease gene annotations

Model Specification

- Define population genetic likelihood using discrete-time Wright-Fisher process

- Specify prior distributions based on evolutionary considerations and empirical observations

- Implement hierarchical structure to share information across genes with similar features

Posterior Inference

- Perform Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling or variational inference for posterior approximation

- Compute posterior means and 95% credible intervals for shet constraint metric

- Validate estimates against held-out essential genes and disease associations

Biological Interpretation

- Classify genes according to constraint percentiles

- Integrate with pathogenic variant interpretations

- Perform enrichment analyses across biological pathways and processes

Validation Steps:

- Assess calibration using posterior predictive checks

- Benchmark against orthogonal functional genomics data

- Compare performance to existing constraint metrics for disease gene prioritization [26]

Visualization of Methodological Evolution

Diagram 1: Methodological evolution showing progression from correlation-based approaches to modern Bayesian frameworks.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Regulon Prediction

| Category | Item | Specification/Version | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | RNA-seq Compendia | Species-specific (e.g., 22,093 genes × 1,253 samples for Arabidopsis) | Training and validation data for regulatory inference | Normalize using TMM method; ensure batch effect correction |

| Validated TF-Target Pairs | Gold-standard datasets from literature | Supervised training and benchmarking | Curate carefully to minimize false positives/negatives | |

| Population Genomic Data | Variant frequencies from gnomAD, 1000 Genomes | Evolutionary constraint inference | Annotate with functional consequences | |

| Software Tools | GeneBayes | Custom implementation (GitHub) | Bayesian inference of selective constraint | Requires fastDTWF for likelihood computations |

| GGRN/PEREGGRN | Containerized implementation | Expression forecasting and benchmarking | Supports multiple regression backends | |

| SBMLNetwork | Latest version (GitHub) | Standards-based network visualization | Implements SBML Layout/Render specifications | |

| fastDTWF | v0.0.3 | Efficient population genetics likelihoods | Critical for scaling to biobank datasets | |

| Computational Libraries | Modified NGBoost | v0.3.12 | Probabilistic prediction with uncertainty | Custom modification for genomic data |

| PyTorch | v1.12.1 | Deep learning implementation | GPU acceleration essential for large models | |

| RDKit | Current release | Chemical structure handling | Critical for PRnet compound representation | |

| Validamycin A | Validamycin A, CAS:50642-14-3, MF:C20H35NO13, MW:497.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| Licoagrochalcone C | Licoagrochalcone C, CAS:325144-68-1, MF:C21H22O5, MW:354.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Workflow for Bayesian Regulon Prediction

Diagram 2: Comprehensive workflow for Bayesian regulon prediction, highlighting iterative model refinement.

The evolution of computational regulon prediction has culminated in the development of sophisticated Bayesian probabilistic frameworks that effectively address the complexities of gene regulatory systems. These approaches represent a paradigm shift from purely descriptive network inference toward predictive models that explicitly account for uncertainty and integrate diverse biological evidence. The integration of evolutionary constraints with functional genomic data has been particularly transformative, enabling more accurate identification of functionally important regulatory relationships.