Advanced Synthetic Biology Approaches for Prokaryotic Gene Cluster Engineering: From Discovery to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary synthetic biology strategies for engineering prokaryotic gene clusters, with a focus on addressing the critical need for novel bioactive compounds, particularly antibiotics.

Advanced Synthetic Biology Approaches for Prokaryotic Gene Cluster Engineering: From Discovery to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary synthetic biology strategies for engineering prokaryotic gene clusters, with a focus on addressing the critical need for novel bioactive compounds, particularly antibiotics. It explores foundational concepts, from biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) mining to the refactoring of silent clusters. The article details high-throughput methodological workflows, including the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle employed in biofoundries and advanced gene editing tools like CRISPR. It further addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, such as host-circuit interactions and metabolic burden, and examines validation frameworks and comparative analyses across diverse microbial chassis. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes cutting-edge developments that are revitalizing antibiotic discovery and the production of valuable natural products.

Unlocking Prokaryotic Potential: Foundations of Gene Cluster Discovery and Analysis

The Urgent Need for Novel Antibiotics and the Role of Synthetic Biology

The rising tide of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most severe threats to modern global healthcare. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one in six laboratory-confirmed bacterial infections in 2023 were resistant to standard antibiotic treatments [1]. Between 2018 and 2023, antibiotic resistance increased in over 40% of the pathogen-antibiotic combinations monitored, with an average annual rise of 5–15% [1] [2]. This silent pandemic is already directly responsible for approximately 1.27 million deaths annually and contributes to nearly five million more [2].

The crisis is particularly acute for Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, which are leading causes of severe bloodstream infections [1]. Globally, over 40% of E. coli and more than 55% of K. pneumoniae isolates are resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, the first-line treatment for these infections [1]. In some regions, including parts of the African Region, resistance rates exceed 70% [1] [2]. This alarming trend underscores the critical need for innovative approaches to antibiotic discovery and development.

Table 1: Global Antibiotic Resistance Patterns for Key Pathogens

| Bacterial Pathogen | First-Line Antibiotic | Global Resistance Rate | Regional Resistance Hotspots |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Third-generation cephalosporins | >40% | African Region (>70%) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Third-generation cephalosporins | >55% | African Region (>70%) |

| Multiple Gram-negative species | Carbapenems | Increasing | Worldwide |

| Multiple Gram-negative species | Fluoroquinolones | Increasing | Worldwide |

Synthetic Biology Approaches for Antibiotic Discovery

Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Refactoring and Heterologous Expression

Microbial natural products have served as a primary source of antibiotics, with the majority originating from soil-dwelling bacteria of the order Actinomycetales [3]. Genomic sequencing has revealed that these organisms contain far more biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) than are expressed under standard laboratory conditions [4]. It is estimated that approximately 90% of native BGCs are transcriptionally silent or "cryptic" under conventional cultivation conditions [4] [5]. Synthetic biology approaches enable activation of these silent BGCs through refactoring and heterologous expression.

BGC refactoring involves replacing native regulatory elements with well-characterized constitutive or inducible promoters to disrupt native transcriptional regulation [4]. This strategy allows researchers to bypass the complex regulatory networks that normally suppress expression. A key advancement in this field is the development of orthogonal transcriptional regulatory modules that function across diverse bacterial hosts [4]. For instance, Ji et al. developed a system in Streptomyces albus J1074 where both promoter and ribosomal binding site (RBS) regions were completely randomized, creating highly orthogonal regulatory cassettes [4]. When applied to refactor the silent actinorhodin BGC, this approach successfully activated production in a heterologous host [4].

Table 2: BGC Refactoring Tools and Applications

| Refactoring Tool/Method | Mechanism | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| mCRISTAR/miCRISTAR | Multiplexed CRISPR-based Transformation-Assisted Recombination for promoter replacement | Simultaneous replacement of up to eight native promoters with synthetic counterparts [4] |

| Completely Randomized Regulatory Cassettes | Randomization of both promoter and RBS regions while partially fixing -10/-35 regions and Shine-Dalgarno sequence | Activation of silent actinorhodin BGC in Streptomyces albus J1074 [4] |

| Metagenomically-Mined Promoters | Mining diverse microbial genomes for natural 5' regulatory elements with broad host range | Identification of promoters functional across Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and other phylogenetic groups [4] |

| iFFL-Stabilized Promoters | TALE-based incoherent feedforward loop for constant expression regardless of copy number | Stable expression of BGCs when transferred from plasmids to chromosomal integration sites [4] |

Engineering Biosynthetic Pathways

Synthetic biology enables rational engineering of antibiotic biosynthetic pathways to generate novel analogs with improved properties. The modular architecture of polyketide synthases (PKS) and non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) makes them particularly amenable to engineering [3]. These mega-enzymes assemble complex natural products in an assembly-line fashion, with each module responsible for incorporating and modifying specific building blocks.

The erythromycin PKS represents a paradigmatic example of this approach. The three mega-enzymes (DEBS-1, DEBS-2, and DEBS-3) that synthesize the erythromycin precursor 6-deoxyerythronolide B (6-DEB) contain 7 modules and 28 enzymatic domains [3]. Researchers have successfully engineered this system by swapping loading modules to alter starter units, exchanging acyltransferase domains to incorporate non-native extender units, and modifying tailoring enzymes to create novel glycosylation patterns [3]. In a landmark study, Menzella et al. demonstrated the combinatorial assembly of synthetic PKS building blocks to generate "unnatural" natural products [3].

Artificial Intelligence-Driven Antibiotic Discovery

Deep Learning for Novel Compound Design

Artificial intelligence has emerged as a transformative tool for antibiotic discovery, enabling the exploration of chemical spaces orders of magnitude larger than previously possible. The Collins laboratory at MIT pioneered this approach using directed-message passing neural networks (D-MPNN) to predict antibacterial activity from chemical structures [6]. Their models led to the discovery of halicin, a structurally unique compound with broad-spectrum activity against multidrug-resistant pathogens, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii [6].

More recently, MIT researchers have employed generative AI to design novel antibiotics against drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [7]. Using two different generative algorithms – chemically reasonable mutations (CReM) and fragment-based variational autoencoder (F-VAE) – the team generated over 36 million theoretical compounds computationally screened for antimicrobial properties [7]. From these, they identified promising candidates (NG1 for gonorrhea and DN1 for MRSA) that are structurally distinct from existing antibiotics and appear to work through novel mechanisms, primarily disrupting bacterial cell membranes [7].

Molecular De-Extinction and Paleoproteome Mining

An innovative approach termed "molecular de-extinction" leverages deep learning to mine the proteomes of extinct organisms for novel antimicrobial peptides [8]. Researchers developed the APEX (antibiotic peptide de-extinction) platform, which uses ensembles of deep-learning models consisting of peptide-sequence encoders coupled with neural networks to predict antimicrobial activity [8]. This system analyzed 10,311,899 peptides from extinct organisms and identified 37,176 sequences with predicted broad-spectrum activity, 11,035 of which were not found in extant organisms [8].

Experimental validation confirmed the activity of 69 synthesized peptides, with lead compounds including mammuthusin-2 (from the woolly mammoth), elephasin-2 (from the straight-tusked elephant), and hydrodamin-1 (from the ancient sea cow) showing efficacy in mouse models of skin abscess and thigh infections [8]. Most of these peptides killed bacteria by depolarizing the cytoplasmic membrane, a mechanism distinct from most known antimicrobial peptides that target outer membranes [8].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: BGC Refactoring and Heterologous Expression

Objective: Activate and express a silent biosynthetic gene cluster in a heterologous host.

Materials:

- Bacterial strains harboring target BGC

- Heterologous expression host (e.g., Streptomyces albus J1074, Myxococcus xanthus DK1622)

- Synthetic promoter libraries

- CRISPR-TAR assembly components

Procedure:

BGC Identification and Analysis

- Identify target BGC using antiSMASH or PRISM software [4]

- Analyze cluster architecture and predicted regulatory elements

BGC Refactoring

Heterologous Expression

- Introduce refactored BGC into optimized heterologous host via conjugation or transformation

- Culture under appropriate conditions for antibiotic production

- Monitor expression using HPLC-MS or bioactivity assays

Compound Characterization

- Isolate and purify compounds from culture extracts

- Determine structure using NMR and mass spectrometry

- Evaluate antimicrobial activity against target pathogens

Protocol: AI-Guided Antibiotic Discovery

Objective: Identify novel antibiotic candidates using deep learning models.

Materials:

- Curated datasets of antimicrobial compounds and their activities

- Computational resources for deep learning (GPU clusters)

- Chemical libraries for virtual screening

- Bacterial strains for validation

Procedure:

Model Training

- Collect and curate training data from public databases (e.g., DBAASP) and in-house sources [8]

- Preprocess chemical structures (SMILES strings or graph representations)

- Train ensemble deep learning models (e.g., D-MPNN) using multitask learning architecture [8]

- Validate model performance using cross-validation and independent test sets

Virtual Screening

Experimental Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Synthetic Biology-Driven Antibiotic Discovery

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Promoter Libraries | Replace native regulatory elements to activate silent BGCs | Randomized regulatory cassettes for Streptomyces albus [4] |

| CRISPR-TAR Systems | Multiplexed genome editing for BGC refactoring | mCRISTAR, miCRISTAR, mpCRISTAR platforms [4] |

| Heterologous Expression Hosts | Provide optimized genetic background for BGC expression | Streptomyces albus J1074, Myxococcus xanthus DK1622 [4] |

| Deep Learning Models | Predict antibacterial activity and design novel compounds | D-MPNN, graph convolutional networks, ensemble APEX [6] [8] |

| Chemical Fragment Libraries | Provide building blocks for generative AI design | Enamine REAL space, 45+ million fragment combinations [7] |

| BGC Databases | In silico identification and analysis of biosynthetic pathways | MIBiG, IMG-ABC, antiSMASH [4] |

| DACN(Tos,Suc-NHS) | DACN(Tos,Suc-NHS), CAS:2411082-26-1, MF:C22H25N3O7S, MW:475.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dabigatran etexilate | Dabigatran Etexilate | Dabigatran etexilate is an oral prodrug and direct thrombin inhibitor for research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human consumption. |

Synthetic biology provides a powerful suite of technologies for addressing the escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance. By enabling the activation of silent biosynthetic gene clusters, engineering of novel antibiotic analogs, and leveraging artificial intelligence for compound design, these approaches are expanding the accessible chemical space for antibiotic discovery. As resistance continues to outpace conventional drug development, the integration of these innovative methodologies offers renewed hope in the ongoing battle against multidrug-resistant pathogens. The urgent need for novel antibiotics demands continued investment in and application of these synthetic biology platforms to ensure a robust pipeline of effective treatments for bacterial infections.

Microbial genomes harbor a vast, largely untapped reservoir of biosynthetic potential encoded within Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs). These clustered sets of genes function as coordinated genetic units responsible for producing specialized metabolites with diverse biological activities, including antibiotics, anticancer agents, immunosuppressants, and siderophores [9] [10]. The ecological and pharmaceutical significance of these compounds cannot be overstated—they mediate critical microbial interactions, serve as virulence factors, and form the foundation of numerous therapeutic agents [11] [10].

Advances in genome sequencing have revealed a startling disparity between the number of predicted BGCs and characterized natural products. Typical microbial genomes contain numerous cryptic or silent BGCs that are not expressed under standard laboratory conditions [12]. For instance, well-studied Streptomyces avermitilis strains contain 40 predicted BGCs, with 23 remaining cryptic, while the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans harbors 56 putative pathways [12]. This hidden biosynthetic potential represents a frontier for novel compound discovery, particularly through synthetic biology approaches that enable activation, optimization, and transfer of these gene clusters across organisms.

BGC Diversity and Evolutionary Dynamics

Distribution and Classification of BGCs

BGCs demonstrate remarkable structural and functional diversity across microbial taxa. Major BGC classes include:

- Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases (NRPS): Large, modular enzymes that function as assembly lines to synthesize diverse peptide natural products, many with medicinal properties [11]

- Polyketide Synthases (PKS): Generate complex polyketide compounds through sequential condensation of carboxylic acid precursors

- Ribosomally synthesized and Post-translationally Modified Peptides (RiPPs): Derived from ribosomal peptides that undergo extensive enzymatic modifications

- NRPS-Independent Siderophores (NIS): Biosynthesize iron-chelating siderophores through alternative enzymatic pathways not involving NRPS machinery [11]

Comparative genomic analyses reveal striking patterns in BGC distribution across bacterial taxa. A comprehensive study of 45 Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus (XP) strains identified 1,000 BGCs belonging to 176 families, with NRPS clusters being most abundant (59% of total BGCs) [13]. In marine bacterial genomes, researchers identified 29 distinct BGC types, with NRPS, betalactone, and NI-siderophores being predominant [11]. Notably, pathogenic species exhibit distinctive BGC signatures; Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates predominantly harbor NRPS-type BGCs, Klebsiella pneumoniae strains frequently contain RiPP-like BGCs, while Acinetobacter baumannii isolates commonly feature siderophore BGCs [10].

Table 1: BGC Distribution Across Bacterial Taxa

| Bacterial Group | Predominant BGC Types | Average BGCs per Genome | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xenorhabdus & Photorhabdus (XP) | NRPS (59%), PKS/NRPS hybrids | 22 | Two- to tenfold higher than other Enterobacteria |

| Marine Bacteria | NRPS, betalactone, NI-siderophore | Varies by species | 29 BGC types identified across 199 strains |

| ESKAPE Pathogens | Species-specific signatures | Varies by species | P. aeruginosa (NRPS), K. pneumoniae (RiPP-like), A. baumannii (siderophore) |

Evolutionary Mechanisms and Sub-Cluster Modularity

BGCs evolve through dynamic processes including horizontal gene transfer, gene duplication, deletion, and rearrangement [14]. Quantitative analyses demonstrate that BGCs experience significantly higher rates of these evolutionary events compared to primary metabolic genes [14]. This rapid evolution facilitates chemical innovation and adaptation to ecological niches.

A fundamental principle in BGC evolution is their modular organization into sub-clusters—co-evolving gene groups that encode specific chemical moieties or functional units [14]. These sub-clusters act as evolutionary building blocks that can be shared, transferred, and recombined between otherwise unrelated BGCs. For example, analysis of 35 BGCs with known connections to specific chemical moieties revealed that >60% of the coding capacity of some BGCs (e.g., those encoding vancomycin and rubradirin) is composed of individually conserved sub-clusters [14]. This "bricks and mortar" model of BGC evolution, where modular "bricks" (sub-clusters) encode key building blocks while individual "mortar" genes provide tailoring, regulation, and transport functions, enables nature to efficiently generate chemical diversity through combinatorial assembly.

This evolutionary modularity provides valuable insights for synthetic biology approaches to BGC engineering. Sub-clusters with known functions represent natural, pre-optimized units that can be harnessed for pathway engineering, potentially offering more predictable outcomes compared to individual part-based strategies [14].

Computational Identification and Analysis of BGCs

Bioinformatics Tools for BGC Prediction

The exponential growth of genomic data has driven development of sophisticated computational tools for BGC identification and analysis. antiSMASH (Antibiotics & Secondary Metabolite Analysis SHell) represents the gold standard for broad-spectrum BGC detection, utilizing profile hidden Markov models (pHMMs) and expert-defined rules to identify known BGC classes across bacterial and fungal genomes [11] [15] [16]. The recently released antiSMASH 7.0 incorporates improved detection algorithms, chemical structure prediction, and enhanced visualization capabilities [11].

While antiSMASH excels at identifying known BGC types, its reliance on predefined rules can limit detection of novel or highly divergent clusters [15] [16]. This limitation has prompted development of machine learning-based approaches that can identify BGCs based on higher-order sequence patterns rather than strict similarity thresholds. DeepBGC employs bidirectional long short-term memory (Bi-LSTM) networks to model sequence context, improving generalization for novel BGC detection [15]. Similarly, RFBGCpred utilizes a random forest classifier with Word2Vec feature extraction to achieve 98.02% accuracy in classifying five major BGC classes (PKS, NRPS, RiPPs, terpenes, and PKS-NRPS hybrids) [15].

Table 2: Computational Tools for BGC Analysis

| Tool | Methodology | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH | pHMMs, rule-based detection | Comprehensive coverage (100+ BGC classes), gold standard | May miss atypical/divergent clusters |

| DeepBGC | Bi-LSTM deep learning | Detects novel BGCs beyond known families | Potential false positives on diverse genomes |

| RFBGCpred | Random Forest + Word2Vec | High accuracy (98.02%) for major classes | Focused on 5 major BGC classes |

| BiG-SCAPE | Sequence similarity networks | Groups BGCs into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) | Requires pre-identified BGCs |

| PRISM | Rule-based + structural prediction | Predicts chemical structures of NRPs/PKs | Limited to specific BGC classes |

Protocol: Computational BGC Mining Workflow

Objective: Identify and characterize biosynthetic gene clusters from microbial genome sequences.

Input Requirements:

- Microbial genome sequence in FASTA or GenBank format

- 8GB RAM minimum, 16GB recommended for larger genomes

- Linux/macOS/Windows with Python 3.7+

Procedure:

Data Retrieval and Quality Control

- Obtain genome sequence from NCBI or other repositories

- Assess assembly quality using QUAST or similar tools

- For metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), estimate completeness with CheckM

BGC Identification with antiSMASH

- Install antiSMASH 7.0:

pip install antismash - Run analysis:

antismash --genefinding-tool prodigal -c 8 --clusterhmmer --asf --pfam2go --cc-mibig --cb-knownclusters --cb-subclusters input.gbk - Parameters: Enable KnownClusterBlast, ClusterBlast, SubClusterBlast, and Pfam domain annotation [11]

- Install antiSMASH 7.0:

BGC Classification with RFBGCpred (optional)

- For focused analysis of major BGC classes, run RFBGCpred:

python RFBGCpred.py -i input.fasta -o output_directory - Supports FASTA, GenBank, and CSV input formats [15]

- For focused analysis of major BGC classes, run RFBGCpred:

Comparative Analysis with BiG-SCAPE

- Prepare GenBank files of identified BGCs

- Run BiG-SCAPE:

python bigscape.py -c 8 --cutoffs 0.3 0.1 --clans-off -i input_dir -o output_dir - Interpret results at 10% and 30% similarity cutoffs to identify Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) [11]

Network Visualization with Cytoscape

- Import BiG-SCAPE network files into Cytoscape 3.10.3

- Annotate nodes with BGC class, taxonomic origin, and chemical products

- Identify conserved/core BGCs versus unique/singleton clusters [11]

Output Interpretation:

- Core BGCs: Identified across multiple strains/species, likely encoding essential functions

- Accessory BGCs: Present in subset of strains, potentially contributing to niche adaptation

- Singleton BGCs: Unique to individual strains, representing recent evolutionary acquisitions

Synthetic Biology Approaches for BGC Activation and Engineering

Heterologous Expression Strategies

Many BGCs remain silent under laboratory conditions due to complex regulatory constraints or lack of appropriate environmental triggers. Heterologous expression provides a powerful strategy to activate these cryptic pathways by transferring them into genetically tractable host organisms [17] [12]. Successful heterologous expression requires several key steps:

BGC Capture and Assembly

- Large BGCs (>50 kb) can be captured using Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which leverages the highly efficient homologous recombination system of yeast [17] [12]

- For refactored pathways, Modular Cloning (MoClo) systems based on Type IIs restriction enzymes enable seamless assembly of multiple DNA fragments in defined linear order [17]

Host Selection and Engineering

Regulatory Override

- Replace native promoters with well-characterized inducible or constitutive systems

- Express pathway-specific activators or delete repressors

- Implement synthetic ribosome binding sites (RBS) to optimize translation efficiency [12]

Protocol: BGC Refactoring and Heterologous Expression

Objective: Activate a cryptic BGC through refactoring and heterologous expression.

Materials:

- Bacterial strains: E. coli GB05-dir, Bacillus subtilis 1A976, Streptomyces coelicolor M1152/M1154

- Vectors: pCAP01 (capture vector), pCRISPomyces-2 (CRISPR/Cas9), pIJ10257 (conjugative transfer)

- Enzymes: Gibson Assembly master mix, restriction enzymes (BsaI, BsmBI), Phusion polymerase

- Growth media: R5, R5A, SFM, LB for Streptomyces; LB, 2xYT for E. coli

Procedure:

BGC Capture and Assembly

- For TAR cloning: Design 60-bp homology arms flanking target BGC, amplify using PCR

- Co-transform with linearized TAR vector into yeast spheroplasts for in vivo assembly [17]

- For MoClo assembly: Digest vector and inserts with Type IIs enzymes (BsaI), ligate in single reaction [17]

- Validate assembly by PCR and restriction digest

Pathway Refactoring

- Identify all coding sequences within BGC using antiSMASH annotation

- Replace native promoters with synthetic counterparts (e.g., PermE, kasOp, SP44)

- Optimize RBS sequences using computational tools (RBS Calculator)

- Assemble refactored pathway using Golden Gate or Gibson Assembly [12]

Conjugative Transfer to Heterologous Host

- For Streptomyces hosts: Introduce vector into methylation-deficient E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002

- Prepare spores or mycelium of Streptomyces recipient, wash with 2xYT

- Mix donor and recipient cells, plate on SFM agar, incubate at 30°C

- After conjugation, overlay with appropriate antibiotics and selection agents [12]

Screening and Metabolite Analysis

- Culture recombinant strains in production media (e.g., R5A, SFM)

- Extract metabolites with ethyl acetate or butanol

- Analyze extracts using LC-MS/MS with positive and negative ionization

- Compare metabolic profiles to control strains using computational tools (GNPS, SIRIUS) [13]

Troubleshooting:

- No metabolite production: Check promoter compatibility, codon usage, precursor availability

- Low titers: Optimize cultivation conditions, media composition, feeding strategies

- Unstable constructs: Implement integrative vectors or chromosomal insertion

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for BGC Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| BGC Identification Tools | antiSMASH 7.0, DeepBGC, PRISM | Computational BGC prediction | antiSMASH: broad detection; ML tools: novel BGC discovery |

| DNA Assembly Systems | Gibson Assembly, MoClo, Yeast TAR | Pathway construction & refactoring | TAR: large fragments (>100 kb); MoClo: modular assembly |

| Specialized Vectors | pCAP01, pCRISPomyces-2, pIJ10257 | BGC capture, editing, transfer | Host-specific replicons, conjugation functions |

| Heterologous Hosts | S. coelicolor M1152, P. putida KT2440, B. subtilis 1A976 | Cryptic BGC expression | M1152: minimized background metabolism |

| Culture Media | R5, R5A, SFM, ISP2 | Secondary metabolite production | Media composition dramatically affects BGC expression |

| Analytical Platforms | LC-MS/MS, GNPS, SIRIUS | Metabolite detection & characterization | MS/MS essential for structural elucidation of novel compounds |

| Mca-SEVNLDAEFK(Dnp) | Mca-SEVNLDAEFK(Dnp)-NH2 Fluorescent Substrate | Mca-SEVNLDAEFK(Dnp)-NH2 is a fluorescent peptide substrate for research use only (RUO). Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| DNA polymerase-IN-3 | DNA polymerase-IN-3, CAS:381689-75-4, MF:C13H12O4, MW:232.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The systematic exploration of biosynthetic gene clusters represents a paradigm shift in natural product discovery. By integrating computational prediction with synthetic biology approaches, researchers can now access the vast "hidden" metabolome encoded within microbial genomes. The modular nature of BGC evolution provides a blueprint for engineering strategies that mimic natural evolutionary processes, while advanced DNA assembly and host engineering techniques enable realization of this potential in practical applications.

Future directions in BGC research will likely focus on several key areas: (1) development of more sophisticated machine learning algorithms capable of predicting chemical structures from sequence data alone; (2) expansion of heterologous host platforms to accommodate increasingly complex BGCs from diverse microbial lineages; and (3) integration of metabolic modeling and flux analysis to optimize production of valuable compounds. As these technologies mature, the systematic mining and engineering of BGCs will continue to drive innovation in drug discovery, agricultural science, and industrial biotechnology, unlocking the immense treasure trove of microbial natural products for applications that benefit human health and society.

In the field of synthetic biology and prokaryotic gene cluster engineering, the discovery and characterization of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) represents a crucial first step in accessing nature's chemical diversity for drug development. Computational mining tools have become indispensable for researchers aiming to rapidly identify and prioritize potential natural product producers from genomic data. Among these, antiSMASH (antibiotics & Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell) and PRISM (PRediction Informatics for Secondary Metabolomes) have emerged as cornerstone technologies that enable genome-driven discovery of bioactive compounds [18] [19]. These tools have transformed natural product discovery from a traditionally activity-guided process to a targeted, sequence-based approach, allowing researchers to navigate the vast landscape of microbial genomes with unprecedented precision.

The integration of these computational tools with synthetic biology frameworks has created powerful synergies for prokaryotic gene cluster engineering. By combining accurate in silico predictions with advanced genetic manipulation techniques, researchers can now accelerate the discovery and production of novel bioactive molecules, including antibiotics, anticancer agents, and immunosuppressants [20] [21]. This article provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for leveraging antiSMASH and PRISM within synthetic biology workflows, with a specific focus on prokaryotic systems.

antiSMASH and PRISM represent complementary approaches to BGC analysis, each with distinct strengths and specialized capabilities. Understanding their core functionalities and differences is essential for selecting the appropriate tool for specific research objectives.

antiSMASH operates primarily as a detection and annotation platform that identifies genomic regions encoding secondary metabolite biosynthesis. Since its initial release in 2011, antiSMASH has evolved into the most widely used tool for BGC detection in both bacterial and fungal genomes [18]. The recently released version 8.0 has expanded its detection capabilities to 101 different BGC types, incorporating improvements in terpenoid analysis, tailoring enzyme annotation, and modular polyketide synthase (PKS) and nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) analysis [18]. antiSMASH functions by using manually curated rules that define what biosynthetic functions must exist in a genomic region to be classified as a BGC. These identifications are made using profile hidden Markov models (pHMMs) and dynamic profiles sourced from public datasets and antiSMASH-specific resources [18].

In contrast, PRISM 4 specializes in chemical structure prediction and biological activity assessment of the metabolites encoded by identified BGCs. Rather than simply detecting cluster boundaries, PRISM connects biosynthetic genes to the enzymatic reactions they catalyze, enabling in silico reconstruction of complete biosynthetic pathways and their final products [19]. This approach incorporates 1,772 hidden Markov models (HMMs) and implements 618 in silico tailoring reactions to predict chemical structures across 16 different classes of secondary metabolites [19]. A key advancement in PRISM 4 is its ability to predict the likely biological activity of encoded molecules using machine learning approaches, providing valuable prioritization criteria for experimental follow-up.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of antiSMASH and PRISM Features

| Feature | antiSMASH | PRISM |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | BGC detection and annotation | Chemical structure prediction |

| BGC Types Detected | 101 cluster types in version 8.0 [18] | 16 classes of secondary metabolites [19] |

| Core Methodology | Profile HMMs and curated rules [18] | HMMs + enzymatic reaction rules [19] |

| Structure Prediction | Limited to specific domains (e.g., NRPS, PKS) | Comprehensive for all supported classes |

| Activity Prediction | Not available | Machine learning-based activity prediction |

| Output Similarity Comparison | KnownClusterBlast, ClusterCompare [18] | Tanimoto coefficient to known compounds [19] |

| Tailoring Enzyme Analysis | Dedicated tailoring tab with MITE database links [18] | 618 in silico tailoring reactions [19] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics for antiSMASH and PRISM

| Metric | antiSMASH | PRISM |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Rate | 96% of reference BGCs (1230/1281) [19] | 96% of reference BGCs (1230/1281) [19] |

| Structure Prediction Rate | 61% of detected BGCs (753/1230) [19] | 94% of detected BGCs (1157/1230) [19] |

| Prediction Accuracy | Lower Tc similarity to true products [19] | Significantly higher Tc similarity to true products [19] |

| Chemical Diversity | Lower molecular complexity metrics [19] | Higher molecular weight, complexity, and NP-likeness [19] |

The complementary nature of these tools is evident in their applications. While antiSMASH excels at comprehensive BGC identification and boundary definition, PRISM provides more accurate and chemically detailed structure predictions. Performance evaluations demonstrate that PRISM 4 generates predicted structures with significantly greater similarity to true cluster products (as measured by Tanimoto coefficients) and produces molecules with higher natural product-like characteristics compared to antiSMASH and other tools [19].

Application Notes for antiSMASH

BGC Detection and Annotation Protocol

Principle: antiSMASH identifies BGCs in genomic data using curated rules based on the presence of specific biosynthetic functions detected via profile HMMs [18].

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Prepare genomic data in FASTA or GenBank format. For novel isolates, ensure proper genome assembly and annotation using tools like RAST or Prokka.

- Analysis Execution:

- Access the antiSMASH web server at https://antismash.secondarymetabolites.org/ or install the standalone version for large-scale analyses.

- Upload the genome file or provide accession numbers for public genomes.

- Select appropriate analysis parameters based on target BGC types (default settings are suitable for most applications).

- Output Interpretation:

- Review the identified BGC regions with color-coded annotations.

- Examine the "Tailoring" tab for detailed information on post-assembly modification enzymes organized by Enzyme Commission categories [18].

- Utilize KnownClusterBlast results to assess similarity to characterized BGCs in the MIBiG database.

- Experimental Validation:

- For Streptomyces strains, implement genetic manipulation systems including conjugal transfer from E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 to Streptomyces spores [22].

- Perform gene knockouts or promoter engineering to activate cryptic BGCs.

- Analyze metabolic profiles using LC-MS/MS after fermentation under appropriate conditions.

Technical Notes:

- antiSMASH version 8.0 includes improved handling of BGCs spanning the origin of replication in circular genomes [18].

- The new "EXTENDS" condition in cluster rules ensures proper detection of all core genes, even when spatially separated [18].

- For terpene BGCs, the updated analysis module provides predictions of terpenoid class, chain length, and potential cyclization patterns [18].

NRPS/PKS Analysis Protocol

Principle: antiSMASH provides detailed analysis of modular enzymes including domain composition, substrate specificity predictions, and identification of inactive domains [18].

Procedure:

- Domain Analysis: Identify core biosynthetic domains (e.g., ketosynthase [KS], acyltransferase [AT], acyl carrier protein [ACP] for PKS; condensation [C], adenylation [A], thiolation [T] for NRPS).

- Substrate Prediction: Review adenylation domain substrate specificity predictions for NRPS clusters.

- Validation Checks: Examine active sites of condensation and epimerization domains for catalytic residues; missing residues are flagged as potentially inactive [18].

- Module Organization: Confirm the colinearity between module organization and predicted biochemical steps.

Technical Notes:

- antiSMASH now includes detection of siderophore-associated β-hydroxylases, interface domains, and α/β-hydrolases [18].

- CoA-ligase (CAL) domains are now recognized as potential starting modules in lipopeptide BGCs [18].

- For additional substrate specificity analysis, use the external PARAS predictor linked from antiSMASH results [18].

Application Notes for PRISM

Chemical Structure Prediction Protocol

Principle: PRISM predicts complete chemical structures by connecting biosynthetic genes to enzymatic reactions, considering all possible sites for tailoring modifications [19].

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Provide genome sequence in FASTA format or BGC regions extracted from antiSMASH analysis.

- Analysis Execution:

- Access the PRISM web application at http://prism.adapsyn.com or use the command-line version for high-throughput analyses.

- Submit genomic data with default parameters for comprehensive analysis.

- Output Interpretation:

- Review predicted chemical structures with attention to combinatorial alternatives.

- Assess Tanimoto coefficients to known natural products for novelty evaluation.

- Examine functional group content and complexity metrics (e.g., Bertz topological index).

- Experimental Validation:

- Correlate predicted structures with LC-MS/MS data from fermentation extracts.

- Use molecular networking approaches (e.g., GNPS) to identify related compounds.

- Isructure-guided isolation of predicted compounds using HPLC and NMR characterization.

Technical Notes:

- PRISM considers all possible sites for tailoring reactions (e.g., halogenation, glycosylation) when generating combinatorial structural predictions [19].

- The maximum Tanimoto coefficient between predicted and true structures is typically higher than the median, reflecting structural uncertainty at specific modification sites [19].

- PRISM predictions show greater structural complexity and natural product-likeness compared to other tools, making them valuable for novelty assessment [19].

Bioactivity Prediction Protocol

Principle: PRISM employs machine learning models trained on chemical structures with known activities to predict likely biological targets of genomically encoded molecules [19].

Procedure:

- Structure Collection: Generate structural predictions for BGCs of interest using PRISM.

- Activity Scoring: Review predicted activity scores against various target classes (e.g., antibacterial, anticancer).

- Priority Ranking: Rank BGCs based on predicted activity profiles and novelty metrics.

- Experimental Validation:

- Test fermentation extracts against target pathogen panels.

- Perform dose-response assays for promising hits.

- Use mode-of-action studies for compounds with predicted specific targets.

Integrated Synthetic Biology Workflow

The true power of computational mining emerges when these tools are integrated with synthetic biology approaches for BGC activation and engineering. The following workflow represents a comprehensive pipeline for genome-driven natural product discovery:

BGC Cloning and Refactoring Protocol

Principle: Silent or poorly expressed BGCs identified through computational mining can be activated via cloning and refactoring in heterologous hosts [21].

Procedure:

- BGC Selection: Identify target BGCs through antiSMASH and PRISM analysis based on novelty, predicted activity, and genetic tractability.

- Vector Design: Design assembly vectors with appropriate antibiotic resistance markers and replication origins for the target host.

- Golden Gate Assembly:

- Domesticate BGC fragments by removing internal restriction sites (BsaI, PaqCI) through silent mutagenesis [21].

- Perform hierarchical assembly: first assemble 2-3 fragments into intermediate vectors, then combine intermediate constructs into the final expression vector [21].

- Use a single Golden Gate reaction with BsaI-HFv2 and T4 ligase for primary assembly, followed by PaqCI and T4 ligase for final assembly [21].

- Heterologous Expression:

- Introduce assembled constructs into optimized heterologous hosts (e.g., Streptomyces coelicolor M1152) via intergeneric conjugation [21].

- Cultivate recombinant strains under various fermentation conditions to activate BGC expression.

- Monitor metabolite production using analytical methods (HPLC, LC-MS).

Technical Notes:

- Hierarchical Golden Gate Assembly achieves nearly 100% efficiency for constructs up to six fragments and significantly higher transformation efficiency compared to one-pot assembly [21].

- For the 23 kb actinorhodin BGC, this approach enabled construction of 23 mutant derivatives with 100% efficiency in a single experiment [21].

- Refactoring through promoter engineering and the use of synthetic interfaces (cognate docking domains, SpyTag/SpyCatcher) can enhance compatibility between heterologous modules [23].

Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) Cycle Implementation

Principle: The DBTL framework enables iterative optimization of modular biosynthetic systems through computational design, assembly, testing, and machine learning [23].

Procedure:

- Design Phase: Deconstruct target natural product structures into biosynthetic units and identify compatible PKS/NRPS modules using predictive tools.

- Build Phase: Combinatorially assemble modular gene fragments using automated Golden Gate Assembly with standardized synthetic interfaces [23].

- Test Phase: Express engineered constructs in heterologous hosts and quantify metabolite production using analytical chemistry approaches.

- Learn Phase: Employ AI-assisted optimization (graph neural networks) to improve module compatibility and predict functional outcomes for subsequent cycles [23].

Technical Notes:

- Synthetic interfaces (cognate docking domains, synthetic coiled-coils, SpyTag/SpyCatcher, split inteins) function as orthogonal connectors to facilitate post-translational complex formation [23].

- The DBTL cycle enables systematic exploration of chemical space through module swapping and pathway derivatization [23].

- Integration of computational predictions with experimental validation creates a knowledge feedback loop for continuous improvement of predictive algorithms.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for BGC Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Assembly Systems | BGC cloning and refactoring | Golden Gate Assembly (BsaI, PaqCI); Gibson Assembly; TAR cloning [21] |

| Heterologous Hosts | BGC expression | Streptomyces coelicolor M1152 (BGC-free); E. coli expression strains [21] |

| Conjugal Transfer System | DNA delivery to actinomycetes | E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 (methylation-deficient) [22] |

| Synthetic Interfaces | Module compatibility engineering | Cognate docking domains; SpyTag/SpyCatcher; synthetic coiled-coils; split inteins [23] |

| Analytical Tools | Metabolite characterization | LC-MS/MS; HPLC; GNPS molecular networking [21] [24] |

| Bioinformatics Databases | BGC comparison and annotation | MIBiG; BiG-FAM; antiSMASH database [18] |

The integration of computational mining tools like antiSMASH and PRISM with synthetic biology approaches has created a powerful paradigm for prokaryotic gene cluster engineering. antiSMASH provides comprehensive BGC detection and annotation capabilities, while PRISM enables accurate chemical structure prediction and bioactivity assessment. When combined with advanced genetic engineering techniques such as Golden Gate Assembly and heterologous expression, these tools form a complete workflow for genome-driven natural product discovery.

The future of this field lies in further tightening the DBTL cycle through improved predictive algorithms, standardized synthetic biology parts, and automated assembly platforms. As these technologies mature, they will dramatically accelerate the discovery and engineering of novel bioactive compounds, addressing the critical need for new therapeutics in an era of increasing antibiotic resistance and complex diseases.

The genomic sequencing of prokaryotes has revealed a vast reservoir of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) with the potential to encode novel bioactive compounds. However, a significant majority of these BGCs are transcriptionally silent under standard laboratory conditions, presenting a major challenge for natural product discovery [25]. Synthetic biology provides a suite of rational engineering strategies to awaken these silent clusters, moving beyond traditional methods like culture condition optimization. This document outlines standardized protocols and reagents for the activation and heterologous expression of prokaryotic BGCs, enabling researchers to systematically convert genomic potential into characterized compounds.

Key Genetic Toolkits and Applications

The transition from random mutagenesis to precision genome engineering has been driven by key technological advances. CRISPR/Cas systems have been particularly transformative, offering editing precision rates of 50–90%, a significant improvement over the 10–40% efficiency of earlier techniques [26]. The table below summarizes the primary genetic tools used for this purpose.

Table 1: Key Genetic Tools for BGC Activation

| Tool Category | Description | Key Application in BGC Activation | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas Systems | RNA-guided nucleases enabling precise genome editing. | Targeted gene knock-ins, knock-outs, and point mutations within silent BGCs; transcriptional activation (CRISPRa) [26]. | High efficiency (50-90%); requires careful gRNA design to minimize off-target effects. |

| Synthetic Transcription Factors (STFs) | Engineered proteins designed to bind and activate specific promoter sequences. | Targeted upregulation of cluster-specific pathway regulators or core biosynthetic genes [25]. | Bypasses the need for understanding native regulatory circuits; highly modular. |

| Promoter Engineering | Replacement of native promoters with strong, inducible alternatives. | Direct activation of BGC genes, decoupling expression from native regulation [25] [27]. | Common replacements include inducible (e.g., Ptet) or constitutive synthetic promoters. |

| Recombineering | Homologous recombination-based genetic engineering. | Markerless gene deletions, insertions, and replacements in a single step [26]. | Highly efficient in model strains; efficiency can vary in non-model organisms. |

| Pyr-Arg-Thr-Lys-Arg-AMC TFA | Pyr-Arg-Thr-Lys-Arg-AMC TFA, MF:C39H58F3N13O11, MW:942.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 1,5-Dibromo-3-ethyl-2-iodobenzene | 1,5-Dibromo-3-ethyl-2-iodobenzene, CAS:1160573-80-7, MF:C8H7Br2I, MW:389.85 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Activation via Promoter Refactoring

This protocol describes the replacement of native promoters within a BGC with a synthetic, inducible promoter to achieve controlled expression.

BGC Analysis and Design:

- Identify all genes within the target BGC using bioinformatics tools (e.g., antiSMASH) [27].

- Design a refactored cluster where the native promoter of each essential gene (core biosynthetic enzymes, positive regulators) is replaced with a strong, orthogonal promoter (e.g., Ptet, Plac).

- Design homology arms (≥500 bp) flanking the insertion site for each promoter swap.

Vector Construction:

- Assemble the refactored BGC in a suitable E. coli-streptomyces shuttle vector using Gibson Assembly or Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR) cloning [27].

- The final construct should contain the entire refactored BGC, the necessary inducible regulator gene (e.g., tetR for Ptet), and appropriate selection markers.

Transformation and Induction:

- Introduce the assembled vector into the host strain (native or heterologous) via conjugation or protoplast transformation.

- Select for positive clones on appropriate antibiotic media.

- For heterologous expression, select a chassis with minimal background metabolism (e.g., Streptomyces coelicolor M1152/M1146) [25].

- Induce expression by adding the relevant inducer (e.g., anhydrotetracycline for Ptet) during mid-log phase growth.

Metabolite Analysis:

- Extract metabolites from the culture supernatant and mycelial pellet with organic solvents (e.g., ethyl acetate).

- Analyze extracts using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) and compare chromatograms to non-induced controls to identify newly produced compounds.

Protocol 2: Heterologous Expression in a Cyanobacterial Chassis

Cyanobacteria are ideal hosts for expressing cyanobacterial BGCs due to their compatible transcriptional and translational machinery [27].

Host and Vector Selection:

- Select a genetically tractable cyanobacterial host (e.g., Anabaena sp. PCC 7120, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803).

- Choose a suicide or shuttle vector compatible with the host's replication system.

BGC Assembly and Modification:

- Amplify the target BGC from genomic DNA. For large clusters (>20 kb), use TAR cloning in yeast [27].

- Optionally, refactor the cluster by replacing native promoters with strong, host-specific promoters (e.g., PpsbA1).

- Codon-optimize the BGC genes for the heterologous host if necessary.

Conjugation into Cyanobacterium:

- Use a tri-parental mating protocol with an E. coli donor strain carrying the BGC vector, an E. coli helper strain providing conjugation functions, and the recipient cyanobacterium.

- Concentrate cyanobacterial cells to a high density and mix with the E. coli strains on a solid filter.

- Incubate under light for 24-48 hours to allow conjugation.

- Resuspend the cells and plate onto selective medium. Incubate under continuous light.

Screening and Production:

- Screen exconjugants via PCR to confirm BGC integration.

- Inoculate positive clones into liquid medium and grow under standard photobioreactor conditions.

- Harvest cells and media, then extract and analyze metabolites as described in Protocol 1.

Table 2: Example Yields from Heterologously Expressed Cyanobacterial Natural Products

| Natural Product | NP Class | BGC Origin | Heterologous Host | Key Modifications | Maximum Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lyngbyatoxin A | NRP | Moorena producens | Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 | Native BGC | 2307 ng mgâ»Â¹ DCW [27] |

| Shinorine | NRP | Fischerella sp. PCC 9339 | Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | Native and refactored BGC | 2.4 mg gâ»Â¹ DCW [27] |

| Hapalindoles | Alkaloid | F. ambigua UTEX 1903 | Synechococcus 2973 | Fully refactored BGC | 2.0 mg gâ»Â¹ DCW [27] |

| APK (Apratoxin) | PK | M. bouillonii | Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 | Promoter change | 9.7 mg Lâ»Â¹ [27] |

| Cryptomaldamide | PK-NRP | M. producens JHB | Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 | Native BGC | 15.3 mg gâ»Â¹ DCW [27] |

Visualizing the Activation Workflow

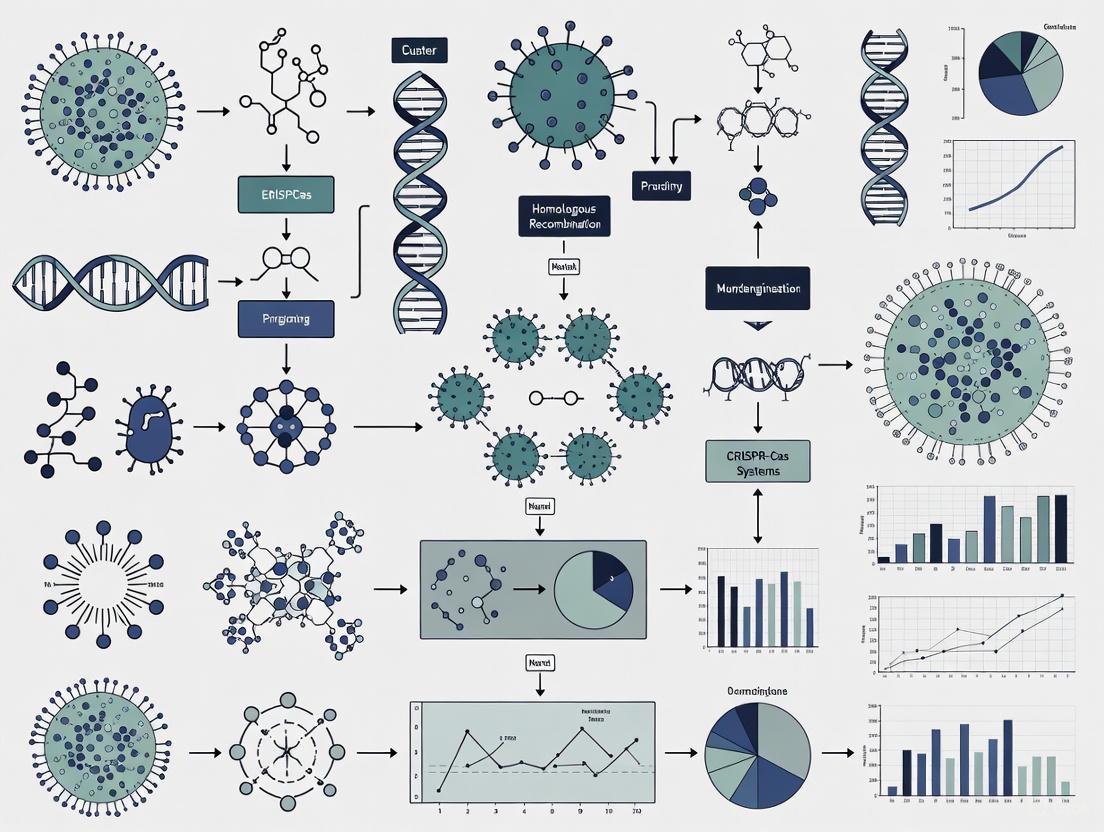

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision process for selecting the appropriate strategy to activate a silent BGC.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A successful activation project relies on a core set of biological reagents and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Reagent / Tool Name | Category | Function / Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH | Bioinformatics | In silico identification and annotation of BGCs in genomic data [27]. | Primary tool for initial BGC discovery. |

| MIBiG | Database | Repository of known BGCs for comparative analysis [27]. | Useful for prioritizing novel BGCs. |

| TAR Cloning | Molecular Biology | Direct capture and assembly of large DNA fragments (>50 kb) in yeast [27]. | Essential for large BGCs. |

| Gibson Assembly | Molecular Biology | One-step, isothermal assembly of multiple DNA fragments [27]. | For constructing refactored clusters. |

| Broad-Host-Range Vectors | Vector | Shuttle vectors that replicate in diverse bacterial hosts (e.g., E. coli-Streptomyces). | pRMS, pKC1139-based vectors. |

| Inducible Promoters | Genetic Part | Engineered promoters for controlled gene expression (e.g., Tet-On, Lac). | Ptet, PtipA for streptomycetes. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Genetic Tool | Plasmid-based system for targeted genome editing and transcriptional activation. | pCRISPR-Cas9 or derivatives. |

| Mca-Ala-Pro-Lys(Dnp)-OH | Mca-Ala-Pro-Lys(Dnp)-OH, MF:C32H36N6O12, MW:696.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Mca-SEVNLDAEFK(Dnp)-NH2 | BACE-1 Fluorogenic Substrate Mca-SEVNLDAEFK(Dnp)-NH2 | Mca-SEVNLDAEFK(Dnp)-NH2 is a fluorescent peptide substrate for measuring BACE-1 activity. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

Building Cell Factories: Methodologies for Cluster Engineering and Heterologous Expression

Biofoundries represent a transformative shift in biotechnology, functioning as integrated facilities that automate the process of biological engineering. These centers leverage advanced robotics, synthetic biology, and computational tools to accelerate the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle for developing engineered biological systems [28]. The core principle of a biofoundry is the systematic automation of this iterative cycle, which consists of: using computational tools to design genetic circuits or metabolic pathways (Design); constructing these designs using automated synthesis and assembly techniques (Build); evaluating the performance of the engineered systems through high-throughput screening (Test); and analyzing the data to refine designs and improve subsequent iterations (Learn) [28]. This integrated approach drastically reduces the time and cost associated with traditional biotechnological research, enabling rapid innovation in synthetic biology, metabolic engineering, and therapeutic development [28]. By automating complex biological workflows, biofoundries enhance reproducibility, scalability, and standardization, making ambitious biological engineering projects more feasible and efficient [28].

The Automated DBTL Cycle: A Detailed Workflow

The power of a biofoundry lies in the seamless integration and automation of the DBTL cycle. This creates a closed-loop system where data from each experiment directly informs and optimizes the next design iteration.

Design Phase

The Design phase transitions biological engineering from a manual art to a predictive science. This stage utilizes a suite of in silico tools for pathway design and component selection. For any given target compound, tools like RetroPath and Selenzyme enable automated metabolic pathway discovery and enzyme selection [29]. Following this, reusable DNA parts are designed with the simultaneous optimization of bespoke ribosome-binding sites (RBS) and enzyme coding regions using tools such as PartsGenie [29]. These genetic elements are then combined into large combinatorial libraries of pathway designs. To make these libraries experimentally tractable, statistical methods like Design of Experiments (DoE) are employed to select a smaller, representative set of constructs that efficiently explore the multidimensional design space [29]. This approach alleviates the need for prohibitively high-throughput construction and screening. Custom software then produces assembly recipes and robotics worklists, facilitating a smooth transition from digital design to physical construction [29].

Build Phase

The Build phase is where digital designs become physical DNA constructs. This stage begins with commercial DNA synthesis or the preparation of standardized genetic parts via PCR [29]. Automated platforms, such as liquid handling robots, then execute DNA assembly using robust, high-efficiency methods like ligase cycling reaction (LCR) [29]. The resulting plasmid constructs are transformed into a microbial chassis (e.g., E. coli). Quality control is critical and is performed via high-throughput automated plasmid purification, restriction digest analysis by capillary electrophoresis, and sequence verification [29]. The trend is moving towards increasingly universal and reproducible assembly pipelines, with AI-guided design now playing a key role in dynamically optimizing assembly protocols and diagnosing failures, which is key to closing the DBTL loop [30].

Test Phase

The Test phase involves high-throughput phenotypic characterization of the constructed microbial strains. Engineered constructs are introduced into selected production chassis and cultivated using automated 96-well deepwell plate growth and induction protocols [29]. The detection and quantification of the target product and key intermediates are then performed. This typically involves automated sample extraction followed by quantitative analysis using techniques like fast ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) [29]. The resulting raw data is processed and extracted using custom-developed, open-source scripts (e.g., in R or Python) to generate structured datasets on strain performance [31] [29]. This automated workflow allows for the rapid generation of high-quality, reproducible data essential for the next phase.

Learn Phase

The Learn phase is the cornerstone of the iterative cycle, where data is transformed into knowledge. Here, statistical methods and machine learning (ML) are applied to the performance data to identify the complex relationships between genetic design factors (e.g., promoter strength, gene order) and observed production titers [29]. For instance, statistical analysis can reveal that vector copy number or the promoter strength of a specific enzyme has the most significant impact on product yield [29]. The insights generated in this phase are used to rationally refine the initial design rules, defining the specifications for a new, improved set of constructs to be built and tested in the next DBTL cycle, thus continuously improving the system [32] [29].

The following diagram illustrates the flow of information and materials through this automated, iterative cycle.

Application Notes: Implementing an Automated DBTL Pipeline for Fine Chemical Production

To illustrate the practical application of an automated DBTL pipeline, we detail its implementation for the microbial production of the flavonoid (2S)-pinocembrin in E. coli [29]. This case study demonstrates how rapid DBTL cycling can achieve significant improvements in product titer.

Experimental Objectives and Workflow

The primary objective was to rapidly identify an optimal genetic configuration for the four-enzyme pathway converting L-phenylalanine to (2S)-pinocembrin. The automated DBTL pipeline was deployed as follows:

- First DBTL Cycle (Library Screening): A combinatorial library of 2,592 potential genetic configurations was designed, varying parameters such as vector copy number, promoter strength for each gene, and gene order. Using Design of Experiments (DoE), this was reduced to a tractable set of 16 representative constructs. All constructs were successfully assembled by the automated platform and screened for pinocembrin production [29].

- Second DBTL Cycle (Focused Optimization): Statistical analysis of the first cycle data identified key limiting factors. The second design round focused on a constrained region of the design space, incorporating these learnings—for instance, using a high-copy-number vector and fixing the most critical gene at the start of the operon [29].

The quantitative results from the two iterative cycles are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance outcomes from iterative DBTL cycles for pinocembrin production in E. coli [29].

| DBTL Cycle | Key Design Changes | Number of Constructs Tested | Maximum Pinocembrin Titer (mg/L) | Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle 1 | Wide exploration of copy number, promoter strength, and gene order. | 16 | 0.14 | Baseline |

| Cycle 2 | High-copy vector; optimized promoter strengths; fixed gene order based on statistical learning. | Not Specified | 88 | ~500 |

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening of Microbial Cultures for Metabolite Production

This protocol describes the automated Test phase for quantifying fine chemical production from engineered E. coli strains in a 96-well format [29].

- Equipment & Software: Liquid handling robot (e.g., Beckman Coulter Biomek); 96-deepwell plates; UPLC system coupled to a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Waters Acquity UPLC with Xevo G2-XS QToF); plate centrifuge; plate shaker/incubator; data processing scripts (e.g., in R).

- Reagents: Lysogeny Broth (LB) medium; appropriate antibiotics; induction agent (e.g., IPTG or arabinose); internal standard for quantification; extraction solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate or acetonitrile).

Procedure:

- Inoculation and Growth: Using a liquid handler, inoculate 1 mL of LB medium in a 96-deepwell plate with single colonies of engineered E. coli strains. Seal the plate with a breathable seal and incubate at 37°C with shaking (250 rpm) for a predetermined period (e.g., 16 hours) to grow starter cultures.

- Production Induction: Dilute the starter cultures into fresh, auto-induction medium to an OD600 of ~0.1. Re-seal the plates and incubate at the optimal production temperature (e.g., 30°C) for 24-48 hours with shaking.

- Sample Extraction: Centrifuge the plates at 4,000 x g for 10 minutes to pellet cells. Using the automated system, transfer a precise volume of supernatant (e.g., 800 µL) to a new deepwell plate. Add a known volume of extraction solvent containing an internal standard (e.g., 400 µL ethyl acetate). Seal the plate, vortex vigorously for 10 minutes, and centrifuge to separate phases.

- Analysis Setup: Automatically transfer a portion of the organic (upper) layer to a new plate for UPLC-MS/MS analysis.

- Metabolite Quantification: Analyze samples via UPLC-MS/MS. Use a calibrated standard curve for the target compound (e.g., pinocembrin) and the internal standard for absolute quantification. Data extraction and peak integration should be automated using custom R or Python scripts.

- Data Management: Save raw data, processed results, and sample metadata in a structured, searchable database (e.g., following FAIR principles) for the

Learnphase [31].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DBTL Automation

The successful operation of an automated biofoundry relies on a standardized toolkit of reliable reagents and molecular tools. The table below lists key solutions for prokaryotic gene cluster engineering.

Table 2: Key research reagents and tools for automated genetic engineering in a biofoundry.

| Reagent / Tool | Function in DBTL Cycle | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Genetic Parts (Plasmids, Promoters, RBS) | Design/Build | Modular DNA elements for predictable pathway assembly and expression tuning [29] [33]. |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Build | Precision genome editing for gene knock-outs, knock-ins, and regulatory control with high efficiency [26] [34]. |

| DNA Assembly Master Mixes (e.g., for LCR or Gibson Assembly) | Build | Automated, high-efficiency assembly of multiple DNA fragments into a single construct [29]. |

| Automated Growth Media & Induction Solutions | Test | High-throughput culturing of engineered bacterial strains under controlled conditions [29]. |

| UPLC-MS/MS with Autosamplers | Test | Automated, quantitative analysis of target metabolites and pathway intermediates from culture samples [29]. |

The biofoundry model, centered on the automated DBTL cycle, represents a paradigm shift in synthetic biology and prokaryotic engineering. By integrating robotics, advanced analytics, and machine learning, it transforms biological design from a slow, labor-intensive process into a rapid, data-driven engineering discipline. As these technologies continue to mature, with AI playing an increasingly central role in design and optimization, biofoundries are poised to dramatically accelerate the development of next-generation bacterial cell factories for sustainable chemistry, therapeutic discovery, and beyond [32] [30].

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins constitute an adaptive immune system in bacteria and archaea that has been repurposed as a revolutionary tool for precision genome engineering [35]. This RNA-guided system enables researchers to make targeted modifications to prokaryotic genomes with unprecedented ease and accuracy, facilitating advanced studies in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering. The fundamental mechanism involves a Cas nuclease complex that is programmed by a short guide RNA (gRNA) to recognize and cleave specific DNA sequences, creating double-strand breaks (DSBs) that are subsequently repaired by the cell's native repair machinery [36] [35]. Unlike previous protein-based editing tools such as zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), CRISPR systems rely on simpler RNA-DNA recognition, making them significantly more accessible and versatile for prokaryotic applications [35].

The classification of CRISPR systems into two broad categories—Class 1 (types I, III, and IV) which utilize multi-protein effector complexes, and Class 2 (types II, V, and VI) which employ single-protein effectors—has important implications for prokaryotic engineering [37]. Class 2 systems, particularly type II (Cas9) and type V (Cas12a/Cpf1), have been most widely adopted for routine genome editing due to their simplicity and efficiency [36]. However, emerging technologies such as CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) systems from the Class 1 category offer new possibilities for large-scale DNA integration without inducing double-strand breaks, expanding the toolbox available for sophisticated prokaryotic genome manipulation [37].

CRISPR-Cas System Mechanisms and Key Components

Molecular Mechanism of CRISPR-Cas Systems

The CRISPR-Cas adaptive immune system operates through three distinct stages: adaptation, expression, and interference. During adaptation, Cas proteins capture fragments of invading foreign DNA and integrate them as new spacers into the CRISPR array within the host genome, creating a molecular memory of past infections [35]. In the expression stage, the CRISPR array is transcribed and processed into short CRISPR RNA (crRNA) molecules that guide the Cas machinery to complementary sequences. Finally, during interference, the Cas protein complex uses the crRNA to identify matching foreign DNA sequences and cleaves them, thereby providing immunity against future invasions [35].

The core components required for implementing CRISPR-Cas genome editing include the Cas nuclease and guide RNA (gRNA). The gRNA is a synthetic fusion of crRNA, which contains the target-specific spacer sequence, and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA), which serves as a scaffold for Cas protein binding [36]. This chimeric single-guide RNA (sgRNA) directs the Cas nuclease to a specific genomic locus through complementary base pairing, with target recognition requiring the presence of a short protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence immediately downstream of the target site [35]. The PAM sequence varies depending on the specific Cas protein used, with Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) recognizing a 5'-NGG-3' PAM, while Cas12a (Cpf1) recognizes a 5'-TTN-3' PAM [38].

Table 1: Key CRISPR-Cas Systems for Prokaryotic Engineering

| System | Class | Effector | PAM | Cleavage Pattern | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 | Class 2, Type II | Single protein | 5'-NGG-3' (SpCas9) | Blunt ends | Gene knockout, gene regulation, base editing |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Class 2, Type V | Single protein | 5'-TTN-3' | Staggered ends (5' overhangs) | Gene insertion, multiplexed editing |

| Type I-F CAST | Class 1 | Multi-protein complex | Depends on guide RNA | No cleavage; RNA-guided transposition | Large DNA insertion (up to 15.4 kb) |

| Type V-K CAST | Class 1 | Single protein (Cas12k) | Depends on guide RNA | No cleavage; RNA-guided transposition | Large DNA insertion (up to 30 kb) |

CRISPR-Cas System Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow for implementing CRISPR-Cas genome editing in prokaryotes, from sgRNA design through to verification of editing outcomes:

Research Reagent Solutions for Prokaryotic CRISPR Editing

Successful implementation of CRISPR-Cas genome editing in prokaryotic systems requires carefully selected molecular tools and reagents. The table below outlines essential components for establishing a robust CRISPR workflow:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Prokaryotic CRISPR-Cas Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas Expression Vectors | pCas, pCas9, pCpf1 | Expresses Cas nuclease in host cells | Use inducible promoters to control timing; codon-optimize for specific hosts [36] |

| sgRNA Expression Systems | pCRISPR, sgRNA plasmids | Expresses target-specific guide RNA | High-copy plasmids with strong promoters preferred; multiple sgRNAs enable multiplexing [36] |

| Repair Templates | ssODNs, dsDNA with homology arms | Provides template for homology-directed repair | 1-kb homology arms typical for large insertions; shorter for point mutations [36] |

| Delivery Mechanisms | Electroporation, conjugation, transduction | Introduces CRISPR components into cells | Efficiency varies by bacterial species; may require optimization [36] |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance, fluorescence | Enriches for successfully edited cells | Counter-selection systems useful for markerless editing [36] |

| CAST System Components | TnsB, TnsC, TniQ (for Type I-F) | Enables RNA-guided transposition | Requires specialized vectors; efficient for large DNA integration [37] |

Advanced CRISPR Technologies for Specialized Applications

CRISPR-Assisted Transposase Systems for Large DNA Integration

CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) systems represent a breakthrough technology for inserting large DNA fragments without relying on homologous recombination or creating double-strand breaks [37]. These systems combine the programmability of CRISPR targeting with the DNA integration capability of transposases, enabling precise insertion of genetic cargo ranging from 5 to 30 kilobases. The Type I-F CAST system from Escherichia coli utilizes a Cascade complex (Cas6, Cas7, Cas8) for target recognition, along with transposase components TnsA, TnsB, TnsC, and TniQ that facilitate the cut-and-paste transposition mechanism [37]. This system has demonstrated remarkable efficiency in prokaryotes, achieving nearly complete insertion of donor sequences up to approximately 15.4 kb in E. coli [37].

The Type V-K CAST system employs the single-effector protein Cas12k along with transposition proteins TnsB, TnsC, and TniQ [37]. Unlike Type I-F systems, Type V-K CAST operates through a replicative pathway that generates cointegrate products, enabling integration of even larger DNA fragments—up to 30 kb has been demonstrated in prokaryotic hosts [37]. The following diagram illustrates the molecular mechanism of CAST systems for programmable DNA integration:

Base Editing and Multiplexed Genome Engineering

Beyond conventional gene knockout and insertion strategies, CRISPR systems have been engineered to enable more sophisticated editing modalities including base editing and multiplexed genome engineering. Base editing utilizes catalytically impaired Cas proteins fused to nucleotide deaminase enzymes to directly convert one DNA base to another without creating double-strand breaks, offering higher efficiency and fewer indel byproducts compared to traditional HDR-based approaches [39]. For multiplexed editing, the ability to program multiple sgRNAs to target several genomic loci simultaneously enables system-level engineering of complex metabolic pathways—a capability particularly valuable for synthetic biology applications in prokaryotes [35].

Experimental Protocols for Prokaryotic CRISPR-Cas Editing

Protocol 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Gene Knockout in E. coli

Objective: To disrupt a target gene in E. coli using the CRISPR-Cas9 system through error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair.

Materials:

- pCas9 plasmid (contains Cas9 gene with inducible promoter)

- pCRISPR plasmid (contains sgRNA expression cassette)

- Electrocompetent E. coli cells

- LB medium with appropriate antibiotics

- Inducer (e.g., arabinose or anhydrotetracycline)

- Primers for verification

Procedure:

- sgRNA Design: Design a 20-nt sgRNA sequence targeting the gene of interest, ensuring the presence of a 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence immediately downstream of the target site.

- sgRNA Cloning: Clone the synthesized sgRNA oligonucleotide into the pCRISPR plasmid using Golden Gate assembly or restriction digestion/ligation.

- Transformation: Co-transform pCas9 and the constructed pCRISPR plasmid into electrocompetent E. coli cells.

- Induction: Grow transformed cells to mid-exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5) and induce Cas9 expression with the appropriate inducer for 4-6 hours.

- Screening: Plate cells on selective media and screen individual colonies for gene disruption using PCR and sequencing.

- Verification: Verify successful editing by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis or Sanger sequencing of the target locus.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Low editing efficiency may require optimization of sgRNA target site or increased induction time.

- High cell mortality may indicate excessive Cas9 expression—titrate inducer concentration.

- Include controls without sgRNA induction to assess background mutation rates.

Protocol 2: CRISPR-Cas12a Mediated Multiplexed Editing in Prokaryotes

Objective: To simultaneously edit multiple genomic loci using Cas12a (Cpf1), which processes its own crRNA arrays, enabling multiplexing without additional processing enzymes.

Materials:

- pCpf1 plasmid (codon-optimized Cas12a with inducible promoter)

- crRNA array plasmid containing multiple guide sequences

- Donor DNA templates for HDR (if performing knock-in)

- Recovery medium (SOC or similar)

- Selection antibiotics

Procedure:

- crRNA Array Design: Design a crRNA array with direct repeats separating individual spacer sequences targeting multiple genomic loci.

- Plasmid Construction: Clone the crRNA array into the appropriate expression vector.

- Transformation: Introduce pCpf1 and the crRNA array plasmid into the prokaryotic host.

- Induction & Editing: Induce Cas12a expression and allow editing to proceed for 6-8 hours.

- Counter-selection: For markerless editing, implement counter-selection to eliminate the editing machinery.

- Screening: Screen colonies for multiplexed editing using multiplex PCR and sequencing.

Applications: This protocol is particularly useful for metabolic engineering applications requiring simultaneous modification of multiple genes in a biosynthetic pathway.

Protocol 3: CAST System-Mediated Large DNA Integration

Objective: To integrate large DNA fragments (10-30 kb) into a specific genomic locus using CRISPR-associated transposase systems.

Materials:

- CAST expression vectors (containing Cas proteins, Tns proteins, and guide RNA)

- Donor plasmid containing the genetic cargo flanked by transposon ends

- Electrocompetent prokaryotic cells

- Antibiotics for selection

Procedure:

- Target Selection: Identify a genomic target site with appropriate PAM recognition for the CAST system.

- Guide RNA Design: Design guide RNA targeting the selected genomic site.

- Donor Construction: Clone the genetic cargo into a donor plasmid containing the appropriate transposon ends (e.g., left-end and right-end sequences).

- System Delivery: Co-transform the CAST expression vectors and donor plasmid into the host cells.

- Integration: Allow transposition to proceed during cell growth and division.

- Screening: Screen for successful integration using antibiotic selection and junction PCR.

- Curing: Eliminate the CAST plasmids through serial passage without selection.

Notes: CAST systems are particularly valuable for inserting entire biosynthetic gene clusters or complex genetic circuits in prokaryotic hosts [37].

Quantitative Parameters for CRISPR System Optimization

Table 3: Key Quantitative Parameters for Optimizing CRISPR-Cas Systems in Prokaryotes

| Parameter | Optimal Range/Value | Impact on Editing Efficiency | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|