A Researcher's Guide to Comparative Genomics Tools for Prokaryotic Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the current landscape of computational tools for prokaryotic comparative genomics, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

A Researcher's Guide to Comparative Genomics Tools for Prokaryotic Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the current landscape of computational tools for prokaryotic comparative genomics, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational concepts, details methodologies for pan-genome analysis and visualization, offers protocols for troubleshooting and optimizing analyses, and outlines best practices for validating results and comparing tool performance. The guide integrates the latest software advancements to empower robust, reproducible genomic research with clinical and biomedical applications.

Core Concepts and the Prokaryotic Genomic Landscape

Defining Comparative Genomics in Prokaryotic Research

Comparative genomics is a foundational method in prokaryotic research that involves the systematic comparison of genomic sequences from different bacteria and archaea. This field leverages the fact that prokaryotes generally possess smaller, less complex genomes lacking the intron-exon structure typical of eukaryotes, making them particularly amenable to comparative analyses [1]. The primary goals of these comparisons are to identify genes responsible for specific traits, understand evolutionary relationships, uncover mechanisms of pathogenicity and antibiotic resistance, and elucidate the genetic basis of ecological adaptation.

The extraordinary adaptability of prokaryotes across diverse ecosystems is largely driven by key evolutionary mechanisms such as horizontal gene transfer (HGT), mutations, and genetic drift [2]. These processes continuously introduce novel genetic variations into microbial gene pools, promoting diversity at both population and species levels. Comparative genomics provides the methodological framework to study these dynamics, offering insights into evolutionary trajectories and adaptive strategies from a population perspective.

Key Analytical Methodologies

Pangenome Analysis

Pangenome analysis represents a crucial method for studying genomic dynamics in prokaryotic populations. The pangenome is conceptualized as the entire repertoire of genes found within a specific prokaryotic species or group, comprising the core genome (genes shared by all individuals), shell genes (found in some but not all individuals), and cloud genes (rare genes present in very few individuals) [2].

Three principal computational approaches have been developed for pangenome analysis:

Reference-based methods utilize established orthologous gene databases (e.g., eggNOG, COG) to identify orthologs by aligning genomic sequences with pre-annotated homologous genes [2]. These methods are highly efficient for analyzing genomes with well-annotated reference data but are less effective for studying new species with substantial novel genetic content.

Phylogeny-based methods classify orthologous gene clusters using sequence similarity and phylogenetic information, often employing techniques such as bidirectional best hits (BBH) or phylogeny-based scoring methods [2]. By constructing phylogenetic trees, these methods aim to reconstruct evolutionary trajectories of genes, though they can be computationally intensive for large datasets.

Graph-based methods focus on gene collinearity and the conservation of gene neighborhoods (CGN), creating graph structures to represent relationships across different genomes [2]. These methods enable rapid identification of orthologous gene clusters but may struggle with accuracy when clustering non-core gene groups, such as mobile genetic elements.

Table 1: Comparison of Pangenome Analysis Methodologies

| Method Type | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference-based | Uses pre-annotated orthologous databases | High efficiency for annotated species | Limited effectiveness for novel species |

| Phylogeny-based | Uses sequence similarity and phylogenetic trees | Reconstructs evolutionary trajectories | Computationally intensive for large datasets |

| Graph-based | Focuses on gene collinearity and neighborhood conservation | Rapid processing of multiple genomes | Lower accuracy with non-core gene groups |

Advanced Pangenome Tools: PGAP2

PGAP2 represents an integrated software package that simplifies various processes including data quality control, pangenome analysis, and result visualization [2]. This toolkit facilitates rapid and accurate identification of orthologous and paralogous genes by employing fine-grained feature analysis within constrained regions, addressing key limitations of earlier tools.

The PGAP2 workflow encompasses four successive steps:

- Data Reading: Compatible with various input formats (GFF3, genome FASTA, GBFF, and annotated GFF3 with sequences) [2].

- Quality Control: Includes outlier detection based on average nucleotide identity (ANI) and unique gene counts, plus generation of visualization reports for features like codon usage and genome composition [2].

- Homologous Gene Partitioning: Employs a dual-level regional restriction strategy to infer orthologs through analysis of gene identity and synteny networks [2].

- Postprocessing Analysis: Generates interactive visualizations displaying rarefaction curves, statistics of homologous gene clusters, and quantitative results of orthologous gene clusters [2].

Systematic evaluation with simulated and gold-standard datasets demonstrates that PGAP2 outperforms previous state-of-the-art tools (Roary, Panaroo, PanTa, PPanGGOLiN, and PEPPAN) in precision, robustness, and scalability for large-scale pangenome data [2].

Functional Genomics Approaches

While comparative genomics identifies genetic variation, functional genomics aims to determine the biological functions of genes and their relationship to phenotypes. Two transformative techniques powered by next-generation sequencing (NGS) have revolutionized this field:

Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) involve sampling and genome sequencing of hundreds of isolates from different environments or conditions to identify genetic elements (single nucleotide polymorphisms, k-mers, or accessory genetic elements) significantly associated with specific phenotypes [3]. Bacterial GWAS successfully identified candidate genes involved in host specificity, virulence, pathogen carriage duration, and antibiotic resistance [3].

Transposon Insertion Sequencing Methods (Tn-seq), including TraDIS, HITS, and INSeq, use large transposon insertion libraries where most non-essential genes contain transposon insertions [3]. After applying selection pressure by growing libraries in defined conditions, sequencing of transposon-genome junctions creates "fitness profiles" indicating the contribution of each gene to survival under those conditions.

Table 2: Key Functional Genomics Methods for Prokaryotic Research

| Method | Principle | Applications | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS | Identifies statistical associations between genetic variants and phenotypes across populations | Host specificity, virulence, antibiotic resistance | Identification of candidate genes underlying complex traits |

| Tn-seq | Profiles fitness effects of gene disruptions through transposon mutagenesis and sequencing | Essential gene discovery, virulence factors, metabolic pathways | Genome-wide fitness contributions of genes under specific conditions |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Pangenome Analysis Using PGAP2

Objective: To identify core and accessory genomic elements across multiple prokaryotic strains and visualize pangenome profiles.

Materials:

- Genomic data in FASTA, GFF3, or GBFF format

- High-performance computing cluster with ≥16 GB RAM

- PGAP2 software (available at https://github.com/bucongfan/PGAP2)

Procedure:

Data Preparation

- Collect genome assemblies for all strains of interest

- Ensure consistent annotation format across datasets

- Organize files in a dedicated project directory

Quality Control

- Execute PGAP2 quality control module

- Review generated HTML reports for genome composition and codon usage

- Identify and potentially exclude outlier strains based on ANI (<95%) or excessive unique gene count

Ortholog Identification

- Run PGAP2 core analysis module with default parameters

- Monitor convergence of orthologous clustering algorithm

- Export preliminary clusters for validation

Postprocessing and Visualization

- Generate rarefaction curves to assess pangenome openness

- Visualize homologous gene cluster statistics

- Extract sequences of core and accessory genes for downstream analysis

Troubleshooting Tip: For large datasets (>500 genomes), utilize checkpointing functionality to resume interrupted analyses.

Protocol 2: Bacterial GWAS for Phenotype-Genotype Association

Objective: To identify genetic variants associated with specific phenotypic traits across bacterial populations.

Materials:

- Cultured bacterial isolates (200-1000 strains)

- Phenotyping assays (antibiotic susceptibility, virulence measures)

- DNA extraction and sequencing kits

- Bioinformatics pipelines (e.g., PySEER, Scoary)

Procedure:

Strain Selection and Sequencing

- Select diverse strains representing population structure

- Extract high-quality genomic DNA

- Perform whole-genome sequencing (≥30× coverage)

Variant Calling

- Map reads to reference genome or perform de novo assembly

- Identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and indels

- Call presence/absence of accessory genes

Population Structure Correction

- Construct phylogenetic tree from core genome SNPs

- Perform principal component analysis (PCA) on genetic variation

- Incorporate phylogenetic or PCA components as covariates in association model

Association Testing

- Apply linear mixed models accounting for population structure

- Perform k-mer-based association testing for comprehensive variant discovery

- Apply multiple testing correction (Bonferroni or false discovery rate)

Validation

- Select top associated variants for experimental validation

- Perform gene deletion/complementation studies

- Confirm phenotypic effects in isogenic backgrounds

Note: Always consider that associated variants may be in linkage disequilibrium with causal mutations rather than being functionally causative themselves.

Visualization and Data Interpretation

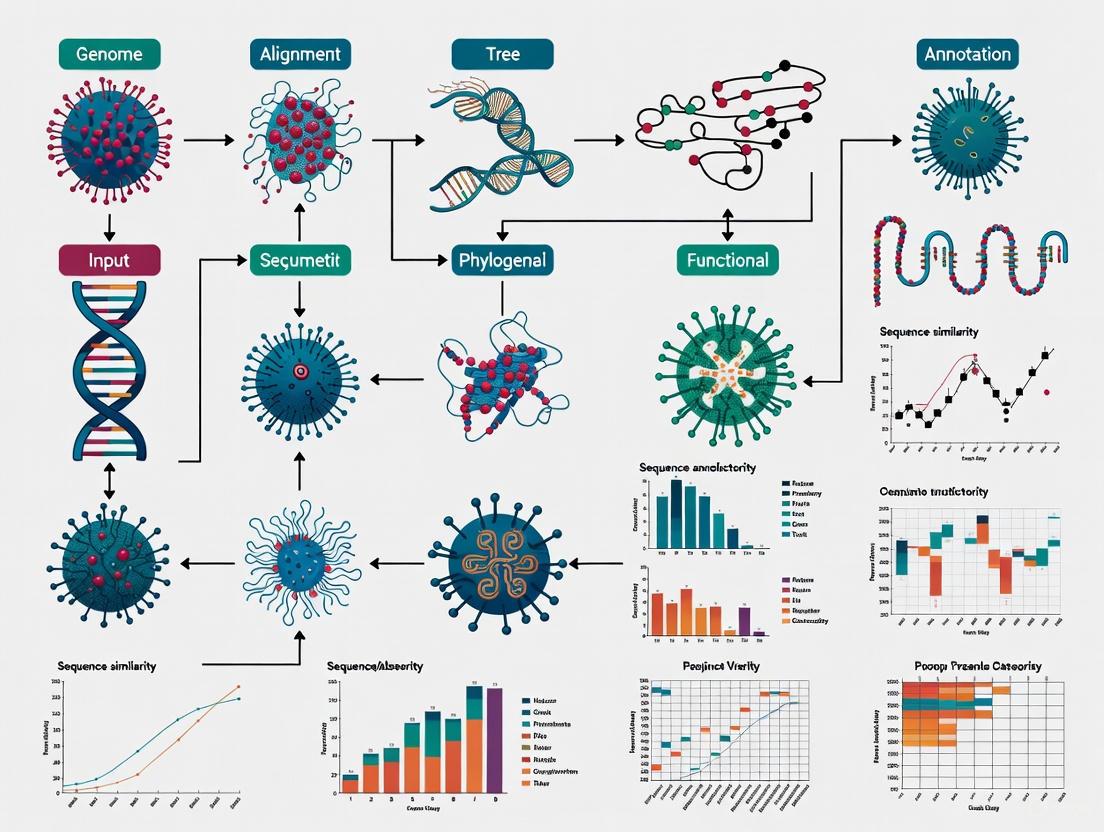

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting comparative genomics data. The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow combining pangenome analysis with functional validation:

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for prokaryotic comparative genomics

For visualizing genome comparisons, tools like the Comparative Genome Viewer (CGV) from NCBI enable exploration of whole-genome assembly-alignments [4]. CGV displays two assemblies horizontally with colored connector lines representing alignments, where forward alignments appear green and reverse alignments purple [4]. This facilitates identification of structural variants and conservation patterns across strains or related species.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Comparative Genomics

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Sources/Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Sequencing Kits | High-quality genome sequencing | Illumina, Oxford Nanopore, PacBio |

| Genome Annotation Tools | Structural and functional gene annotation | Prokka, NCBI Prokaryotic Annotation Pipeline |

| Orthology Databases | Reference-based ortholog identification | eggNOG, COG, OrthoDB |

| Pangenome Analysis Software | Identification of core and accessory genomes | PGAP2, Roary, Panaroo |

| Variant Callers | SNP and indel detection | Snippy, GATK, FreeBayes |

| Association Study Tools | Phenotype-genotype association mapping | PySEER, Scoary, PLINK |

| Transposon Mutagenesis Systems | Genome-wide functional screening | mariner-based systems, EZ-Tn5 |

| Visualization Platforms | Comparative genomics data exploration | CGV, Phandango, BRIG |

Comparative genomics continues to evolve as a cornerstone of prokaryotic research, with advancing methodologies enabling increasingly sophisticated analyses. The integration of pangenome analysis with functional genomics approaches like GWAS and Tn-seq creates a powerful framework for connecting genomic variation to biological function. As sequencing technologies become more accessible and analytical tools more refined, comparative genomics will continue to drive discoveries in microbial evolution, pathogenesis, and adaptation, ultimately informing drug development and therapeutic strategies against pathogenic prokaryotes.

Comparative genomics serves as a cornerstone of modern prokaryotic research, enabling scientists to decipher the evolutionary dynamics, functional adaptations, and genetic diversity of bacterial species. The dramatic reduction in sequencing costs has fueled an exponential growth in available genomic data, making advanced comparative analysis more accessible than ever [5]. Central to these analyses are three key genomic features: orthologs, paralogs, and synteny. Orthologs are genes in different species that evolved from a common ancestral gene by speciation, typically retaining the same function over evolutionary time. Paralogs are genes related by duplication within a genome that often evolve new functions. Synteny refers to the conserved order of genomic elements across different species, providing critical evidence for inferring orthology and understanding genome evolution [6] [7]. These concepts have moved from theoretical frameworks to practical tools that drive discovery in antimicrobial resistance research, virulence mechanism studies, and evolutionary biology. This protocol details the methodologies for identifying and analyzing these features, with particular emphasis on their application in prokaryotic genome analysis through contemporary bioinformatics tools.

Key Concepts and Quantitative Parameters

The accurate identification of orthologs and paralogs relies on quantifying specific genomic features and relationships. The following parameters are essential for characterizing homology clusters and interpreting pan-genome profiles.

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters for Characterizing Homologous Gene Clusters

| Parameter | Description | Application in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) | Measures the average nucleotide sequence similarity between orthologous genes or genomic regions [2] [5]. | Used for quality control to identify outlier strains and define species boundaries; a common threshold is 95% [2]. |

| Bidirectional Best Hit (BBH) | Two genes from two different genomes that are each other's best match in pairwise sequence comparison [2]. | A primary criterion for inferring orthology before applying synteny-based refinement [2]. |

| Contrast Ratio | Numerical expression of the difference in light between foreground (text) and background colors [8]. | Critical for creating accessible data visualizations; minimum 4.5:1 for standard text and 3:1 for large text [8]. |

| Gene Diversity Score | Evaluates the conservation level and variation within an orthologous gene cluster [2]. | Helps assess the reliability of orthologous clusters and their evolutionary conservation [2]. |

| Gene Connectivity | Within a gene identity network, this measures the degree of similarity and connectedness between genes [2]. | Used to evaluate the coherence and quality of inferred orthologous gene clusters [2]. |

Protocols for Identification of Orthologs and Paralogs

Protocol 1: Ortholog Inference via Fine-Grained Feature Analysis with PGAP2

PGAP2 employs a multi-step process that integrates sequence identity with genomic context to accurately partition homologous genes. The following workflow is adapted for the analysis of thousands of prokaryotic genomes [2].

I. Input Data Preparation and Quality Control

- Input Formats: Accepts GFF3, genome FASTA, GBFF, or annotated GFF3 with genomic sequences. The tool can handle a mixture of these formats simultaneously [2].

- Representative Genome Selection: If no specific reference strain is designated, PGAP2 automatically selects a representative genome based on gene similarity across all input strains [2].

- Outlier Detection: Identifies anomalous strains using two complementary methods:

- Feature Visualization: Generates interactive HTML and vector plots for assessing data quality, displaying features such as codon usage, genome composition, and gene completeness [2].

II. Data Abstraction and Network Construction

- Gene Identity Network: Constructs a network where nodes represent genes and edges represent the degree of sequence similarity between them [2].

- Gene Synteny Network: Constructs a parallel network where edges represent adjacent genes—specifically, those that are one position apart in the genome, capturing gene order conservation [2].

III. Ortholog Inference via Dual-Level Regional Restriction

- Regional Refinement: The inference process traverses subgraphs in the identity network but evaluates gene clusters only within a predefined identity and synteny range. This strategy confines the search radius, drastically reducing computational complexity [2].

- Feature Analysis: Within this restricted region, the reliability of potential orthologous clusters is evaluated against three criteria:

- Cluster Merging: Gene clusters meeting the reliability criteria are merged. The synteny network is updated, and the process iterates until no more clusters meet the merging criteria [2].

IV. Post-Processing and Result Visualization

- High-Identity Merge: Nodes with exceptionally high sequence identity (often from recent duplications via Horizontal Gene Transfer) are merged [2].

- Profile Generation: The post-processing module generates interactive visualizations of the pan-genome profile, including rarefaction curves and statistics of homologous gene clusters [2].

- Downstream Analysis: PGAP2 integrates workflows for sequence extraction, single-copy phylogenetic tree construction, and bacterial population clustering [2].

Protocol 2: Functional Analysis of Specificity-Determining Residues

This methodology leverages the functional divergence between orthologs and paralogs to identify key amino acid residues that determine functional specificity, such as in bacterial transcription factors [7].

I. Sequence Dataset Curation

- Identify Orthologs: For a gene family of interest, compile a comprehensive set of orthologous sequences from multiple bacterial genomes. These sequences are assumed to share conserved functional specificity [7].

- Identify Paralogs: Within the same genomes, identify paralogous sequences that belong to the same protein family but are predicted to have divergent functions [7].

II. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Grouping

- Perform a multiple sequence alignment for all collected orthologous and paralogous sequences.

- Partition the aligned sequences into two groups based on their established functional specificity (e.g., orthologs with conserved function in Group A, paralogs with divergent function in Group B) [7].

III. Statistical Correlation Analysis

- Apply a statistical method to identify residues where the amino acid variation strongly correlates with the predefined grouping (orthologs vs. paralogs).

- The underlying assumption is that residues responsible for functional specificity will be conserved within orthologs but will differ in the paralogs [7].

IV. Structural Validation and Experimental Design

- Map the predicted specificity-determining residues onto a available three-dimensional protein structure.

- Analyze their spatial location to determine if they cluster in functional domains, such as DNA-binding or ligand-binding sites [7].

- Use these predictions to design targeted experiments (e.g., site-directed mutagenesis) to rationally re-design protein specificity [7].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core computational workflow for ortholog identification as implemented in modern tools like PGAP2, integrating both sequence identity and syntenic information.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful comparative genomics research relies on a suite of computational tools and curated biological data. The following table details essential "research reagents" for prokaryotic ortholog and synteny analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Prokaryotic Comparative Genomics

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| PGAP2 | Software Pipeline | An integrated package for pan-genome analysis that performs quality control, infers orthologs via fine-grained feature networks, and provides visualization [2]. |

| Orthologous Gene Databases (eggNOG, COG) | Reference Database | Pre-computed databases of orthologous groups used by reference-based methods to annotate and identify orthologs in newly sequenced genomes [2]. |

| Bidirectional Best Hit (BBH) Algorithm | Computational Method | A core algorithm for initial ortholog prediction by identifying gene pairs that are each other's best match in pairwise genome comparisons [2]. |

| Conserved Gene Neighbors (CGN) | Genomic Feature | Preserved gene order across different genomes; used as supporting evidence for orthology and to refine gene clusters in graph-based methods [6] [2]. |

| Simulated Datasets | Benchmarking Resource | Datasets with known evolutionary relationships used for the systematic evaluation and validation of ortholog identification methods [2]. |

| Specialized Functional Databases | Annotation Database | Databases focused on specific gene types (e.g., antimicrobial resistance, virulence factors) for functional annotation of identified orthologs and paralogs [5]. |

| Rebamipide Mofetil | Rebamipide Mofetil, CAS:1527495-76-6, MF:C25H26ClN3O5, MW:483.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Reltecimod | Reltecimod | Reltecimod is a synthetic peptide CD28 antagonist for research on necrotizing soft tissue infections (NSTI) and immune response. For Research Use Only. |

Analysis and Interpretation of Results

Interpreting the output of ortholog and synteny analyses is critical for drawing meaningful biological conclusions. The gene diversity score and connectivity metrics generated by tools like PGAP2 help characterize the evolutionary conservation of gene clusters [2]. Synteny provides crucial supporting evidence for orthology assignments; for instance, if two genes a in different species are putative orthologs, the additional conserved synteny of flanking genes c and d strengthens this inference [6]. Furthermore, the functional annotation of orthologous clusters against specialized databases can reveal genomic islands of virulence or antibiotic resistance, linking evolutionary relationships to phenotypic outcomes [5]. The quantitative parameters, such as average identity and uniqueness to other clusters, provide insights into the dynamics of genome evolution, helping to distinguish between stable core genes and rapidly accessory genes [2].

Comparative genomics provides a powerful framework for understanding the genetic basis of microbial diversity, adaptation, and function. For prokaryotic genome analysis, three methodological pillars have emerged as fundamental: pan-genome analysis, which catalogs the complete gene repertoire across strains; phylogenetic analysis, which reconstructs evolutionary relationships; and variant detection, which identifies genomic differences ranging from single nucleotides to large structural changes. These approaches have been revolutionized by next-generation sequencing technologies and the development of sophisticated bioinformatics tools that can handle the vast datasets now being generated [2] [9].

In prokaryotic research, these analyses are crucial for uncovering the mechanisms behind pathogenicity, antibiotic resistance, ecological adaptation, and metabolic specialization. The integration of AI and machine learning into bioinformatics tools has further enhanced their precision, with some platforms reporting accuracy improvements of up to 30% while significantly reducing processing time [9]. This protocol outlines the key methodologies, tools, and applications for each analysis type, providing researchers with practical guidance for implementing these approaches in prokaryotic genomics studies.

Pan-Genome Analysis

Conceptual Framework and Definitions

The pan-genome represents the total complement of genes found within a species or phylogenetic clade, comprising the core genome (genes shared by all individuals), shell genome (genes present in multiple but not all individuals), and cloud genome (genes unique to few individuals) [10]. This concept, first described in bacterial studies, has transformed our understanding of prokaryotic diversity by revealing how accessory genes contribute to functional versatility and ecological adaptation [2] [10].

In prokaryotes, pan-genome analysis has illuminated the extraordinary genetic diversity within species, driven primarily by horizontal gene transfer, mutations, and genetic drift [2]. The analysis shifts focus from a single reference genome to a population perspective, enabling researchers to identify strain-specific adaptations, understand evolutionary trajectories, and discover genes associated with specific phenotypes like virulence or substrate utilization.

Table 1: Pan-Genome Components and Characteristics

| Component | Definition | Typical Characteristics | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Genome | Genes present in all strains | Housekeeping genes, essential cellular functions | High conservation, structural and metabolic functions |

| Shell Genome | Genes present in multiple but not all strains | Niche-specific adaptations, regulatory elements | Variable distribution, functional specialization |

| Cloud Genome | Genes present in few or single strains | Recently acquired genes, mobile genetic elements | Strain-specific adaptations, horizontal transfer |

Methodological Approaches and Tools

Pan-genome analysis methodologies have evolved to address the challenges of processing thousands of prokaryotic genomes. Current methods can be broadly categorized into three approaches: reference-based (using established orthologous gene databases), phylogeny-based (using sequence similarity and phylogenetic information), and graph-based (focusing on gene collinearity and conservation of gene neighborhoods) [2].

PGAP2 represents a state-of-the-art toolkit that employs fine-grained feature analysis within constrained regions to rapidly identify orthologous and paralogous genes [2]. Its workflow encompasses four successive steps: (1) data reading compatible with various input formats (GFF3, genome FASTA, GBFF); (2) quality control with outlier detection based on average nucleotide identity (ANI) and unique gene counts; (3) homologous gene partitioning through dual-level regional restriction strategy; and (4) post-processing analysis with visualization outputs [2]. For larger eukaryotic genomes or highly heterozygous species, transcript-focused approaches like GET_HOMOLOGUES-EST offer a cost-effective alternative by analyzing coding sequences rather than complete genomes [10].

Figure 1: Generalized Pan-genome Analysis Workflow. The process begins with multiple input genomes, proceeds through quality control and gene clustering, and results in a comprehensive pan-genome profile with visualization outputs.

Application Protocol: Prokaryotic Pan-Genome Analysis with PGAP2

Objective: Construct a pan-genome profile from multiple prokaryotic genomes to identify core and accessory genes and their functional associations.

Materials:

- Genomic sequences in FASTA format or annotations in GFF3/GBFF format

- High-performance computing cluster with minimum 16GB RAM

- PGAP2 software (available at https://github.com/bucongfan/PGAP2)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation and Input

- Collect genome assemblies for all strains to be analyzed

- Ensure consistent annotation formats where possible

- Prepare a directory containing all input files

Quality Control and Representative Selection

- Run PGAP2 with quality control parameters:

pgap.py -i input_dir --qc - Review generated HTML reports on codon usage, genome composition, and gene completeness

- Identify potential outlier strains based on ANI (<95% similarity to representative) or elevated unique gene counts

- Run PGAP2 with quality control parameters:

Orthologous Gene Cluster Identification

- Execute core analysis:

pgap.py -i input_dir --cluster - PGAP2 employs a dual-level regional restriction strategy to identify orthologs through fine-grained feature analysis

- The algorithm evaluates gene diversity, connectivity, and bidirectional best hit criteria

- Execute core analysis:

Pan-genome Profile Construction

- Generate quantitative outputs using distance-guided construction algorithm

- Classify genes into core, shell, and cloud compartments based on distribution patterns

- Extract sequences for each gene cluster for downstream functional annotation

Visualization and Interpretation

- Examine rarefaction curves to assess pan-genome openness

- Analyze functional enrichment in different genomic compartments

- Correlate accessory gene content with phenotypic traits

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For large datasets (>100 genomes), use checkpointing to resume interrupted analyses

- If computational resources are limited, consider a two-step approach analyzing subsets of genomes

- Validate unexpected gene distributions by checking alignment quality and genomic context

Phylogenetic Analysis

Foundations of Microbial Phylogenetics

Phylogenetic analysis reconstructs evolutionary relationships among microorganisms, providing a framework for studying microbial diversity, evolution, and population structure. Unlike simple taxonomic classifications, phylogenetic trees represent genetic similarities and evolutionary history through branch lengths and topological relationships [11]. For prokaryotes, phylogenetic analysis has been transformed by whole-genome sequencing, which provides substantially more information than traditional single-gene approaches like 16S rRNA sequencing.

Phylogenetic trees serve as crucial connectors between upstream bioinformatics processes (sequence processing, alignment) and downstream analyses (diversity measures, association studies) [11]. Methods like UniFrac dissimilarity leverage phylogenetic information to quantify community differences in microbial ecology studies, highlighting the practical importance of accurate tree construction [11].

Tools and Methods for Phylogenetic Reconstruction

Modern phylogenetic tools for prokaryotes must accommodate diverse data sources, including isolate genomes, metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), and single-cell genomes. PhyloPhlAn 3.0 provides a comprehensive solution that automatically selects appropriate phylogenetic markers based on the relatedness of input genomes, using species-specific core genes for strain-level analyses and universal markers for deeper phylogenetic relationships [12].

The software integrates over 230,000 publicly available microbial sequences and can construct phylogenies at multiple resolutions—from strain-level trees to large phylogenies comprising >17,000 microbial species [12]. For example, when analyzing 135 Staphylococcus aureus isolates, PhyloPhlAn 3.0 used 1,658 core genes (from 2,127 precomputed S. aureus core genes) present in ≥99% of genomes to reconstruct a high-resolution phylogeny that showed strong correlation (Pearson's r=0.992) with manually curated reference trees [12].

Table 2: Phylogenetic Analysis Tools for Prokaryotic Genomes

| Tool | Methodology | Optimal Use Case | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PhyloPhlAn 3.0 | Multi-resolution marker genes | Isolate genomes and MAGs from species to phylum level | Automatic database integration, scalable to >17,000 species |

| GToTree | Concatenated core gene alignment | Single species or closely related groups | Automated reference genome retrieval |

| Roary | Pangenome-based profiling | Strain-level phylogenies within species | High accuracy for closely related genomes |

| MLST | Multi-locus sequence typing | Rapid typing and initial classification | Fast but with reduced phylogenetic accuracy |

Application Protocol: Microbial Phylogenetics with PhyloPhlAn 3.0

Objective: Reconstruct a phylogenetic tree for prokaryotic genomes to understand evolutionary relationships and population structure.

Materials:

- Assembled genomes (complete or draft) in FASTA format

- Computational resources with 8GB RAM per core

- PhyloPhlAn 3.0 software and database

Procedure:

- Data Preparation

- Ensure genome assemblies meet minimum quality standards (completeness, contamination)

- For metagenome-assembled genomes, check completeness with tools like CheckM

- Organize input genomes in a dedicated directory

Database Selection and Marker Gene Identification

- Run PhyloPhlAn 3.0 in automatic mode:

phylophlan -i input_genomes -o output_dir --database phylophlan - The software automatically determines optimal phylogenetic resolution and selects appropriate marker genes

- For known species, use species-specific mode:

--diversity highfor strain-level resolution

- Run PhyloPhlAn 3.0 in automatic mode:

Multiple Sequence Alignment and Trimming

- PhyloPhlAn 3.0 performs alignment using MAFFT or MUSCLE

- Alignment trimming removes poorly aligned regions using trimAl or similar tools

- For large datasets, the UPP alignment method provides improved scalability

Phylogenetic Tree Construction

- The software concatenates marker gene alignments into a supermatrix

- Tree inference uses maximum likelihood methods (RAxML, IQ-TREE, or FastTree)

- Support values are calculated via bootstrapping (100 replicates recommended)

Tree Visualization and Interpretation

- Generate publication-quality figures with ggtree or iTOL

- Animate trees with taxonomic and functional annotations

- Correlate phylogenetic clustering with phenotypic data

Figure 2: Phylogenetic Analysis Workflow. The process begins with input genomes, identifies appropriate marker genes, performs sequence alignment and trimming, and concludes with phylogenetic tree construction.

Validation and Quality Assessment:

- Compare topological consistency between different inference methods

- Check for concordance between single-gene trees and the species tree

- Assess branch support values; consider collapsing poorly supported nodes (<70% bootstrap)

- Verify that taxonomic outliers have biological justification rather than representing artifacts

Variant Detection

Variant Types and Biological Significance

Variant detection encompasses the identification of genetic differences ranging from single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to large structural variants (SVs). In prokaryotes, these variations underlie phenotypic diversity, antimicrobial resistance, virulence, and environmental adaptation. Structural variants—defined as variations ≥50 base pairs—include deletions, insertions, duplications, inversions, translocations, and complex rearrangements that significantly impact gene structure and regulatory regions [13] [14].

The functional impact of SVs is often more profound than small variants because they can simultaneously affect multiple genes, alter gene dosage through copy-number variations (CNVs), or disrupt regulatory landscapes. In bacterial genomes, SVs frequently result from mobile genetic elements, phage integration, or homologous recombination between repetitive elements [13]. Recent studies have demonstrated that SVs are unevenly distributed across bacterial genomes and may exhibit subgenome asymmetry in polyploid species, reflecting differential selection pressures [13].

Detection Methods and Tools

Variant detection methodologies have evolved with sequencing technologies. While short-read sequencing enabled comprehensive SNP discovery, the accurate detection of SVs required the development of long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio Oxford Nanopore) and specialized analytical tools [13] [14].

NanoVar represents a specialized workflow for SV detection in long-read sequencing data, optimized for efficiency and reliability across various study designs, including genetic disorders, population genomics, and non-model organisms [14]. The protocol enables researchers to identify and analyze SVs in a typical human dataset within 2-5 hours after read mapping, demonstrating its practical efficiency [14].

For prokaryotic genomes, SV detection must account for unique genomic features including high gene density, operon structures, and the presence of plasmid sequences. Pangenome approaches have proven particularly valuable, as they enable the detection of presence-absence variations (PAVs) that define accessory genomic components and contribute to functional diversification [13].

Table 3: Variant Types and Detection Approaches

| Variant Type | Size Range | Detection Methods | Biological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNPs | Single nucleotide | Short-read alignment, Bayesian calling | Amino acid changes, regulatory effects |

| Indels | 1-50 bp | Local realignment, split-read mapping | Frameshifts, protein truncations |

| Structural Variants | ≥50 bp | Long-read alignment, assembly-based | Gene dosage changes, rearrangements |

| Presence-Absence Variants | Gene-level | Pangenome graphs, read depth analysis | Accessory gene content, niche adaptation |

Application Protocol: Structural Variant Detection with Long-Read Data

Objective: Identify and characterize structural variants in prokaryotic genomes using long-read sequencing data.

Materials:

- Long-read sequencing data (Oxford Nanopore or PacBio)

- Reference genome in FASTA format

- NanoVar software package

- Computing resources with 32GB RAM recommended

Procedure:

- Data Preparation and Quality Control

- Base-call raw sequencing data (if necessary) using Guppy or similar tools

- Assess read quality (Q-score >7 for Nanopore, >20 for PacBio) and read length distribution

- Filter out low-quality reads and artifacts

Read Mapping and Alignment

- Map reads to reference genome using minimap2 or NGMLR:

minimap2 -ax map-ont reference.fasta reads.fastq > aligned.sam - Convert SAM to BAM format and sort:

samtools view -Sb aligned.sam | samtools sort -o sorted.bam - Generate read coverage statistics to identify potential regions of interest

- Map reads to reference genome using minimap2 or NGMLR:

Structural Variant Calling

- Run NanoVar SV detection:

nanovar -r reference.fasta -b sorted.bam -o output_dir - Adjust sensitivity parameters based on project goals: higher sensitivity for discovery studies, higher specificity for validation

- For population studies, use cohort analysis mode to identify shared and private SVs

- Run NanoVar SV detection:

Variant Filtering and Annotation

- Apply quality filters: minimum supporting reads (≥3), mapping quality, and variant size

- Annotate SVs with genomic features (genes, regulatory elements) using bedtools

- Classify SVs by type (deletion, insertion, inversion, etc.) and genomic context

Validation and Visualization

- Validate high-impact SVs by PCR and Sanger sequencing

- Visualize SVs in genomic context using IGV or similar browsers

- Generate circos plots or linear genome diagrams showing SV distribution

Figure 3: Structural Variant Detection Workflow. The process begins with long-read sequencing data, proceeds through quality control, read mapping, variant calling, and annotation, resulting in a set of validated variants.

Interpretation Guidelines:

- Prioritize SVs affecting coding sequences, regulatory regions, or antibiotic resistance genes

- Consider SV recurrence across multiple strains as evidence of positive selection

- Correlate SV presence with phenotypic data where available

- Be cautious of potential false positives in repetitive regions or areas with poor coverage

Integrated Applications in Prokaryotic Research

Successful implementation of comparative genomics analyses requires both computational tools and curated biological resources. The following table outlines key reagents and datasets essential for prokaryotic genome analysis.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Prokaryotic Comparative Genomics

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Databases | NCBI RefSeq, UniProt, EggNOG | Orthology assignments, functional annotation | Publicly available online |

| Quality Control Tools | CheckM, FastQC, QUAST | Assembly and sequence quality assessment | Open source |

| Analysis Toolkits | PGAP2, PhyloPhlAn 3.0, NanoVar | Specialized analytical workflows | GitHub repositories |

| Visualization Platforms | IGV, ggtree, BRIG | Data exploration and result presentation | Open source |

| Curated Genome Collections | Gold-standard datasets, Type strain genomes | Method validation and benchmarking | Public repositories |

Case Study: Integrated Analysis ofStreptococcus suisZoonotic Strains

A comprehensive analysis of 2,794 zoonotic Streptococcus suis strains demonstrates the power of integrating multiple comparative genomics approaches [2]. The study employed PGAP2 to construct a pan-genomic profile that revealed extensive genetic diversity driven by accessory gene content. Phylogenetic analysis using PhyloPhlAn 3.0 placed these strains in the context of global diversity, identifying distinct clades associated with zoonotic potential. Variant detection uncovered specific structural variations in virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance genes that differentiated pathogenic from commensal lineages.

This integrated approach provided insights into the evolutionary mechanisms driving the emergence of zoonotic strains, identifying genomic islands and phage-related elements as key contributors to pathogenicity. The study exemplifies how combining pan-genome, phylogenetic, and variant analyses can uncover biologically meaningful patterns in large bacterial datasets.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of prokaryotic comparative genomics is rapidly evolving, with several trends shaping future methodologies. AI integration is transforming variant calling and functional prediction, with tools like DeepVariant achieving superior accuracy compared to traditional methods [9]. The application of large language models to "translate" nucleic acid sequences represents a particularly promising frontier, potentially unlocking new approaches to analyze DNA, RNA, and amino acid sequences [9].

Cloud-based platforms are democratizing access to advanced genomics by connecting over 800 institutions globally and making powerful computational resources available to smaller labs [9]. Simultaneously, increased focus on data security implements advanced encryption protocols and access controls to protect sensitive genetic information [9]. These technological advances, combined with growing datasets spanning diverse microbial populations, promise to further enhance our understanding of prokaryotic genomics and its applications in medicine, biotechnology, and fundamental biology.

Comparative genomics of prokaryotes relies fundamentally on the public availability of genomic data stored in three primary repositories that form the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (INSDC): the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) in the United States, the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) in Europe, and the DNA Database of Japan (DDBJ). These organizations synchronize their data daily, ensuring researchers can access identical datasets regardless of which repository they use [15]. This triad represents the most comprehensive collection of publicly available nucleotide sequences globally, serving as an indispensable resource for genomic discoveries, comparative analyses, and drug development research.

For prokaryotic genome analysis, these repositories provide diverse data types - from raw sequencing reads to fully assembled and annotated genomes - that enable researchers to investigate genomic variation, evolutionary relationships, horizontal gene transfer, and pathogenicity islands across bacterial and archaeal lineages. The structured organization and standardized submission processes ensure data reproducibility and interoperability, which are critical for robust comparative genomic studies.

Each INSDC partner maintains specialized resources and analytical tools tailored to different aspects of prokaryotic genome analysis, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Core Data Resources and Analytical Tools for Prokaryotic Genomics

| Repository/Resource | Primary Function | Key Features for Prokaryotic Research | Accession Prefix Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) | Raw sequencing data storage [15] | Stores raw reads from various platforms; facilitates reproducibility and reanalysis | SRR, ERR, DRR |

| NCBI RefSeq | Curated reference sequences | Manually reviewed genomes with consistent annotation | NC, NZ |

| NCBI GenBank | Primary sequence database [16] | Comprehensive collection of all submitted sequences; includes WGS and complete genomes | CP, CHR |

| European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) | Comprehensive nucleotide data | Alternative submission portal to NCBI; synchronized data | ERS, ERX, ERR |

| Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) | Automated genome annotation [17] [16] | Annotates bacterial/archaeal genomes using protein family models and ab initio prediction | - |

The Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) warrants particular attention for prokaryotic researchers. This NCBI service automatically annotates bacterial and archaeal genomes by combining alignment-based methods with ab initio gene prediction algorithms. PGAP identifies protein-coding genes using a multi-step process that compares open reading frames to libraries of protein hidden Markov models (HMMs), RefSeq proteins, and proteins from well-characterized reference genomes [17]. For non-coding elements, it identifies structural RNAs (5S, 16S, and 23S rRNAs) using RFAM models via Infernal's cmsearch, and tRNA genes using tRNAscan-SE with specialized parameter sets for Archaea and Bacteria [17]. The pipeline also detects mobile genetic elements, including phage-related proteins and CRISPR arrays, providing comprehensive annotation critical for comparative genomic analyses.

Data Submission Protocols

NCBI SRA Submission Workflow

Submitting sequencing data to public repositories ensures scientific reproducibility and maximizes research impact. The following protocol outlines the submission process to NCBI SRA, which mirrors similar workflows for ENA submission.

Table 2: Essential Metadata Requirements for SRA Submission

| Metadata Category | Specific Requirements | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| BioProject | Project-level information | Principal investigator, project objectives, scope |

| BioSample | Sample-specific attributes [18] | Organism, collection date/location, tissue type, environmental conditions |

| Library Preparation | Experimental methodology [18] | Library source (genomic DNA, RNA), selection method (PCR, enrichment), strategy (WGS, amplicon) |

| Sequencing Platform | Instrument information [18] | Illumina MiSeq, NovaSeq; PacBio; Oxford Nanopore |

| Sequencing Type | Technical parameters [18] | Single-end vs. paired-end, read length |

Step-by-Step Submission Protocol:

BioSample Creation: Before submitting sequences, create BioSample entries describing the biological source materials. Log in to the NCBI Submission Portal, select "BioSample," and download the appropriate batch submission template (e.g., "Invertebrate" for environmental prokaryote samples) [18]. Required fields include

sample_name,organism, and at least one ofisolate,host, orisolation_source. Include as many attributes as possible (e.g.,collection_date,geo_loc_name,lat_lon,temperature) to enhance data reproducibility [18]. Upload the completed spreadsheet to receive SAMN accessions numbers for each sample.BioProject Registration: Create a BioProject to organize all data related to your research initiative. In the Submission Portal, select "BioProject," choose applicable data types (e.g., "Raw sequence reads"), specify project scope ("Single organism" or "Multi-species"), and provide target organisms and descriptive project title and description [18]. Link previously created BioSamples to this project by entering their SAMN accessions. Upon processing, you will receive a PRJNA accession number.

SRA Metadata and File Preparation: Prepare sequencing data and metadata. For each sequencing experiment, gather information on: library source (e.g., "genomic DNA"), selection method (e.g., "PCR" for amplicon studies), strategy (e.g., "AMPLICON" or "WGS"), layout (e.g., "PAIRED"), and instrument model [19] [18]. Compress FASTQ files using gzip and calculate MD5 checksums for file verification [19].

File Upload and Submission: Upload compressed sequence files to the SRA secure upload area via an FTP client like

lftp[19]. Then, in the Submission Portal, start a new "Sequence Read" submission, link to your BioProject, and provide the prepared experiment metadata and file information, including MD5 checksums [18]. NCBI will validate the submission and provide SRA accessions (beginning with SRR) upon successful processing.

For ENA submissions, the process is similar but utilizes the Webin portal, where users upload files to a designated dropbox and submit metadata via spreadsheet templates that closely mirror NCBI's requirements [20] [19].

Genome Annotation Submission

For complete prokaryotic genomes, researchers can request annotation through PGAP during GenBank submission via the Genome Submission Portal [16]. The pipeline automatically identifies protein-coding genes, structural RNAs, tRNAs, and mobile genetic elements, producing comprehensive annotation ready for public release [17]. PGAP can process both complete genomes and draft whole-genome shotgun (WGS) assemblies consisting of multiple contigs, classifying them as WGS or non-WGS based on assembly completeness [16].

Data Access and Analytical Workflows

Accessing Public Data

Researchers can access publicly available data through multiple interfaces:

- Direct SRA Access: The SRA website provides search and download capabilities for raw sequencing data, with options for controlled access for human data or immediate public access for non-human data [15].

- Programmatic Access: Tools like

prefetchfrom the SRA Toolkit enable command-line downloads of SRA data, which can be converted to FASTQ format usingfastq-dumpfor downstream analysis [21]. - Automated Pipelines: Workflow managers like Nextflow can automate large-scale data retrieval and processing. The

biopy_sra.nfpipeline demonstrates how to process hundreds of SRA datasets in parallel, handling downloading, format conversion, and quality control with built-in reproducibility and error-handling capabilities [21].

Analytical Tools for Comparative Genomics

NCBI provides specialized tools for comparing prokaryotic genomes:

- BLAST Suite: Find regions of sequence similarity between bacterial genomes using specialized BLAST databases like ClusteredNR, which groups proteins at 90% identity and length to improve search efficiency [22].

- Comparative Genome Viewer (CGV): Visually compare two assembled genomes at whole-genome, chromosome, or regional levels to identify structural variations [22].

- Multiple Sequence Alignment Viewer: Analyze alignments of homologous genes from multiple prokaryotic strains to identify conserved residues and potential functional domains [22].

The following workflow diagram illustrates a complete comparative genomics study utilizing INSDC resources:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful prokaryotic genomics research relies on both computational tools and experimental reagents. Table 3 catalogs key solutions referenced in the search results.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Prokaryotic Genomics

| Reagent/Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in Prokaryotic Genomics |

|---|---|---|

| PGAP (Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline) | Automated genome annotation [17] [16] | Structural and functional annotation of bacterial and archaeal genomes |

| tRNAscan-SE | tRNA gene detection [17] | Identification of 99-100% of tRNA genes with minimal false positives |

| Infernal/cmsearch | Non-coding RNA alignment [17] | Detection of structural RNAs using covariance models |

| PILER-CR/CRT | CRISPR array identification [17] | Finds clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| GeneMarkS-2+ | Ab initio gene prediction [17] | Predicts protein-coding genes in regions lacking homology evidence |

| Nextflow | Workflow management [21] | Orchestrates scalable, reproducible genomic analysis pipelines |

| BLAST | Sequence similarity search [22] | Finds homologous regions between prokaryotic genomes |

The INSDC repositories - NCBI, ENA, and DDBJ - provide the essential foundation for prokaryotic comparative genomics research through their comprehensive, interoperable data resources. Effective utilization of these resources requires understanding their specialized components: SRA for raw sequencing data, RefSeq for curated references, and PGAP for standardized annotation. The structured submission protocols ensure data quality and reproducibility, while the diverse analytical tools enable sophisticated comparative analyses across microbial taxa. As sequencing technologies advance and datasets expand, these repositories will continue to be indispensable for investigations into prokaryotic evolution, pathogenesis, and metabolic diversity, ultimately accelerating drug discovery and microbial biotechnology innovation.

In the field of prokaryotic genomics, the ability to efficiently process, annotate, and compare genomic data across thousands of strains is fundamental to understanding genetic diversity, evolutionary dynamics, and functional adaptation. The foundation of any comparative genomics workflow relies on the use of standardized file formats that enable the seamless exchange and interpretation of data between bioinformatics tools and databases [2]. This article provides a detailed examination of three cornerstone formats—GFF3, GBFF, and FASTA—framed within the context of modern prokaryotic genome analysis. We explore their technical specifications, roles in analytical pipelines like pan-genome analysis, and provide structured protocols for their effective application in research settings.

Format Specifications and Comparative Analysis

FASTA Format

The FASTA format is a foundational, text-based format for representing nucleotide or amino acid sequences using single-letter codes [23]. Its simplicity and wide adoption make it a near-universal standard for storing raw sequence data.

- Structure: A FASTA file begins with a single description line, starting with a ">" character, followed by lines of sequence data. The description line contains a unique sequence identifier (SeqID) and optional descriptive information [24] [23].

- SeqID Requirements: The SeqID should be unique for each sequence, contain no spaces, and be limited to 25 characters or less. Permissible characters include letters, digits, hyphens, underscores, periods, colons, asterisks, and number signs [24].

- Usage in Genomics: FASTA files typically store raw genomic sequences, such as entire chromosomes or contigs, which serve as the reference for subsequent annotation and analysis [25]. They do not contain any annotation information themselves.

GFF3 Format

The General Feature Format version 3 (GFF3) is specifically designed for storing genome annotations in a structured, machine-readable tabular format [25]. It details the locations and properties of genomic features—such as genes, exons, CDS, and regulatory elements—relative to a reference sequence.

- File Structure: A GFF3 file consists of nine tab-separated columns. The key columns are:

seqid(sequence identifier),source(annotation source),type(feature type),startandend(coordinates),strand, andattributes(semicolon-separated list of feature properties) [26] [27]. - Critical Attributes: The

IDattribute provides a unique identifier for a feature, while theParentattribute establishes hierarchical relationships (e.g., grouping exons under a transcript) [28]. For GenBank submissions, thelocus_tagattribute is required for gene features, andproductnames are required for CDS and RNA features [26]. - Prokaryotic Considerations: For prokaryotic annotation, gene features should use the type "gene," while more specific Sequence Ontology (SO) types like "rRNAgene" or "tRNAgene" should be converted to "gene." Pseudogenes are flagged with a

pseudogene=<TYPE>attribute on the gene feature [26].

GBFF Format

The GenBank Flat File (GBFF) format represents a comprehensive record for a nucleotide sequence, integrating metadata, annotation, and the sequence itself into a single file [29]. It is based on the Feature Table Definition published by the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (INSDC) [29].

- Comprehensive Nature: Unlike GFF3, which typically stores annotations separate from sequence data, GBFF files are self-contained, including the annotated features and the complete nucleotide sequence [29] [30].

- Data Structure: The format includes a header section with metadata (such as organism, taxonomy, and reference information), followed by a feature table listing all annotated genomic elements with their qualifiers, and concluding with the raw nucleotide sequence [29].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Genomic File Formats

| Characteristic | FASTA | GFF3 | GBFF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Store raw nucleotide/protein sequences | Store genomic feature annotations | Comprehensive record with sequence, annotation, and metadata |

| Sequence Data | Included (as single-letter codes) | Not included; references an external sequence | Included (in a dedicated section) |

| Annotation Data | None | Structured feature locations and hierarchies | Structured feature table with qualifiers |

| Key Identifiers | SeqID (from description line) | ID and Parent attributes in column 9 |

Locus tag, gene symbol, accession numbers |

| Standardization | De facto standard | Sequence Ontology (SO) terms | INSDC Feature Table Definition |

Integrated Workflow for Prokaryotic Pan-Genome Analysis

Modern prokaryotic genomics often involves pan-genome analysis to characterize the full complement of genes within a species, encompassing core genes present in all strains and accessory genes found in subsets [2]. Tools like PGAP2 (Pan-Genome Analysis Pipeline 2) are designed to handle thousands of genomes and accept GFF3, GBFF, and FASTA files as input, demonstrating how these formats function within an integrated analytical workflow [2].

The following diagram illustrates a typical prokaryotic pan-genome analysis workflow integrating the three file formats.

Workflow Diagram Title: Prokaryotic Pan-Genome Analysis with PGAP2

Workflow Description

- Data Input and Validation: The process begins with heterogeneous input data. PGAP2 accepts GFF3 files (with companion FASTA sequences), GBFF files, or a combination of formats [2]. The tool validates the data and organizes it into a structured binary file for efficient processing.

- Quality Control and Feature Visualization: PGAP2 performs automated quality control, which may include selecting a representative genome and identifying outlier strains based on Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) or the number of unique genes [2]. Interactive reports are generated to visualize features like codon usage and genome composition.

- Homologous Gene Partitioning via Fine-Grained Feature Analysis: This is the core analytical step. PGAP2 employs a dual-level regional restriction strategy to infer orthologous genes efficiently. It constructs two networks: a gene identity network (edges represent sequence similarity) and a gene synteny network (edges represent gene adjacency) [2]. By analyzing features within constrained identity and synteny ranges, the tool clusters orthologous genes while resolving paralogs.

- Pan-Genome Profile Construction and Visualization: The final steps involve constructing the pan-genome profile, often using algorithms like the distance-guided (DG) construction method [2]. The pipeline generates comprehensive visualizations, such as rarefaction curves and statistics on homologous gene clusters, providing insights into genome dynamics and diversity.

Experimental Protocol: Utilizing File Formats in a Pan-Genome Study

This protocol outlines the steps for a pan-genome analysis of a set of prokaryotic strains using integrated GFF3, GBFF, and FASTA files, based on the PGAP2 methodology [2].

Data Acquisition and Preparation

- Gather Genomic Data: Collect the genomic data for all strains in the study. This may involve downloading GBFF files from NCBI or generating GFF3 and corresponding FASTA files through de novo assembly and annotation of sequencing reads.

- Ensure Format Consistency: If using GFF3, verify that the

seqidin the first column of the GFF3 file exactly matches the sequence identifier in the corresponding FASTA file [26]. - Validate GFF3 Files: Use standalone GFF3 validators to check for syntactic correctness. Ensure critical attributes like

locus_tagfor gene features andproductfor CDS/RNA features are present for GenBank-compliant submissions [26].

Input Data Organization for PGAP2

- Specify Input Directory: Place all input files (a mix of

.gff,.gbff,.fna, etc.) in a single directory. - Run PGAP2: Execute the PGAP2 pipeline, specifying the input directory and output location. PGAP2 will automatically detect the file format based on the suffix and process the data accordingly [2].

- Review QC Reports: Examine the generated quality control reports (in HTML or vector format) to identify any outlier strains or data quality issues before proceeding with full analysis [2].

Execution and Result Interpretation

- Monitor Analysis: The pipeline will automatically execute the steps of homologous gene partitioning and pan-genome profile construction.

- Analyze Outputs: The primary output includes a set of orthologous gene clusters. Key quantitative parameters to examine are:

- Average Identity: Mean sequence identity within a cluster.

- Gene Diversity Score: Assesses the conservation level of orthologous genes.

- Cluster Uniqueness: Helps distinguish core (shared) and accessory (strain-specific) genes [2].

- Visualize Results: Use the generated visualizations (rarefaction curves, cluster statistics) to interpret the pan-genome's openness (core vs. accessory gene distribution) and infer evolutionary dynamics.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| PGAP2 Software | Integrated pipeline for prokaryotic pan-genome analysis | Accepts GFF3, GBFF, and FASTA inputs; performs QC, ortholog clustering, and visualization [2] |

| GFF3 Validator | Verifies syntactic correctness of GFF3 files before submission or analysis | Useful for initial troubleshooting of GFF3 formatting issues [26] |

| Sequence Ontology (SO) | Controlled vocabulary for feature types in GFF3 files | Ensures consistent interpretation of terms like "CDS," "mRNA," "pseudogene" [26] |

| locus_tag | A unique identifier for a gene feature in a GFF3/GBFF file | Required for gene features in GenBank submissions; can be assigned via attribute or command-line prefix [26] |

| ANI (Average Nucleotide Identity) | Metric for genomic similarity used in QC to identify outlier strains | A strain with ANI <95% to a representative genome may be flagged as an outlier [2] |

The interoperability of GFF3, GBFF, and FASTA formats provides the foundational framework for robust and scalable prokaryotic genome analysis. GFF3 offers a flexible and rich environment for detailed annotation, GBFF serves as a comprehensive, self-contained record, and FASTA provides the essential raw sequence data. As genomic datasets continue to expand in scale and complexity, the precise use of these formats, as demonstrated in advanced pipelines like PGAP2, will remain critical for extracting meaningful biological insights from the vast landscape of prokaryotic diversity.

Workflows and Tools for Pan-genome and Locus Analysis

Within the framework of comparative genomics tools for prokaryotic genome analysis research, pan-genome analysis has emerged as a fundamental methodology. It aims to characterize the entire gene repertoire of a species, encompassing genes shared by all strains (the core genome) and those present in only a subset (the accessory genome) [31]. The drive to analyze thousands of genomes, coupled with the need to manage annotation errors and genomic diversity, has fueled the development of sophisticated computational pipelines. Among these, PGAP2 and Panaroo represent two advanced, integrated tools designed to address the limitations of earlier methods. PGAP2 emphasizes high-speed processing and quantitative feature analysis [2], while Panaroo employs a graph-based approach to correct common annotation errors, leading to a more accurate representation of the pan-genome [32]. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these pipelines, along with structured protocols for their application in prokaryotic genomics research.

Tool Comparison: PGAP2 vs. Panaroo

The selection of an appropriate pan-genome analysis pipeline is a critical decision that directly influences biological interpretations. The table below provides a systematic comparison of PGAP2 and Panaroo based on their core attributes.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of PGAP2 and Panaroo

| Feature | PGAP2 | Panaroo |

|---|---|---|

| Core Methodology | Fine-grained feature networks with a dual-level regional restriction strategy [2] | Graph-based algorithm that corrects annotation errors using genomic context [32] |

| Primary Input Formats | GFF3, GBFF, Genome FASTA (with --reannotate) [33] |

Annotated assemblies in GFF3/GTF format with corresponding FASTA files [32] [34] |

| Key Innovation | Quantitative characterization of homology clusters using diversity scores and high-speed processing [2] | Identifies and merges fragmented genes, collapses diverse families, and filters potential contamination [32] |

| Error Handling | Quality control via outlier detection (ANI, unique gene count) and visualization reports [2] | Proactive correction of errors from fragmented assemblies, mis-annotation, and contamination [32] |

| Scalability & Speed | Ultra-fast; constructs a pan-genome from 1,000 genomes in ~20 minutes [2] [33] | More computationally intensive than Roary, but robust for large cohorts [34] |

| Typical Use Case | Large-scale analyses requiring speed and quantitative output on well-annotated data [2] | Cohorts with variable annotation quality or projects where clean gene presence/absence calls are paramount [34] |

| Strengths | High accuracy, comprehensive workflows, superior scalability, and extensive visualization [2] | Robustness to annotation noise, reduction of spurious gene families, and superior ortholog clustering [32] [35] |

Workflow and Functional Logic

Understanding the logical flow of each pipeline is essential for effective utilization. The following diagrams, created using the DOT language, illustrate the core workflows of PGAP2 and Panaroo.

PGAP2 Workflow

Panaroo Workflow

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for PGAP2 Analysis

Application: Constructing a high-resolution pan-genome from thousands of prokaryotic genomes.

1. Input Preparation and Tool Installation

- Installation: The recommended method is to use Conda for managing dependencies. Alternatively, use the Mamba solver for faster performance [33].

- Input Data: Place all genome files in a single directory (

inputdir/). PGAP2 supports mixed input formats, including:

2. Execution of the Main Analysis

- Run the complete PGAP2 pipeline with a single command:

- This command executes the four core steps of the PGAP2 workflow [2]:

- Data Reading: Validates and processes all input files into a structured binary file.

- Quality Control: Performs automatic outlier detection based on Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) and unique gene counts. Generates interactive HTML reports for features like codon usage and genome composition.

- Homologous Gene Partitioning: The core analytical step. It builds gene identity and synteny networks, then applies a fine-grained feature analysis under a dual-level regional restriction strategy to identify orthologs accurately and rapidly.

- Postprocessing: Generates the final pan-genome profile, statistical summaries, and visualization reports.

3. Advanced and Modular Execution

- The pipeline can be run in modular steps for finer control or restarting from checkpoints.

- Preprocessing only:

- Postprocessing (e.g., for statistical analysis or tree building):

Protocol for Panaroo Analysis

Application: Generating a polished pangenome, especially from datasets with variable annotation quality or assembly fragmentation.

1. Input Preparation and Tool Installation

- Installation: Panaroo is available via its GitHub repository and can be installed with Conda.

- Input Data Standardization: Consistent annotation is crucial. Panaroo requires GFF3 files and their corresponding genome FASTA files. A provided script can convert NCBI RefSeq annotations to a compatible Prokka-like GFF format [35].

2. Execution and Mode Selection

- Run Panaroo with the required input and output directories.

- Critical Parameter: Clean Mode. Panaroo offers modes that dictate its handling of potential errors [32]:

--clean-mode strict: Aggressively removes potential contamination and erroneous annotations. Recommended for phylogenetic studies or when rare plasmids are not a focus.--clean-mode sensitive: Does not remove any gene clusters, preserving rare genetic elements like plasmids. Use with caution as it may include more erroneous clusters.--clean-mode moderate: A balanced approach between the two.

3. Downstream Analysis Integration

- Panaroo produces a gene presence-absence matrix and a fully annotated graph in GML format for visualization in tools like Cytoscape [32].

- The package includes scripts for downstream analyses, such as determining gene gain and loss rates and identifying coincident genes.

- It interfaces easily with association study tools like

pyseerto investigate links between gene presence/absence and phenotypes [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful pan-genome analysis relies on a set of key "research reagents," which in this context are primarily datasets, software, and parameters.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Pan-genome Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Description | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Annotated Genomic Assemblies | The primary input data, consisting of genome sequences and their corresponding gene annotations. | Standardization using a single annotation tool (e.g., Prokka) across the cohort is highly recommended to minimize bias [34]. |

| GFF3/GBFF Format Files | Standardized file formats that encapsulate both gene feature locations and, in the case of GBFF, the nucleotide sequence. | Ensures compatibility with PGAP2, Panaroo, and other major pipelines. Conversion scripts are often available [33] [35]. |

| Conda/Mamba Environment | A package and environment management system that simplifies the installation of complex bioinformatics software and their dependencies. | Crucial for reproducing the exact software environment used in an analysis, ensuring consistency and stability [33]. |

| Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) | A metric used for quality control to identify genomic outliers that may not belong to the target species group. | Used by PGAP2 in its preprocessing stage to filter data [2]. |

| Gene Clustering Algorithm (e.g., CD-HIT) | The underlying engine that performs the initial rough grouping of genes based on sequence similarity. | Panaroo uses CD-HIT for its initial clustering. PGAP2 employs its own fine-grained feature network [2] [32]. |

| Presence-Absence Matrix (PAV) | The fundamental output of pan-genome analysis, representing the distribution of each gene cluster across all analyzed genomes. | Serves as the input for numerous downstream analyses, including association studies and population genetics [34] [35]. |

| Remibrutinib | Remibrutinib, CAS:1787294-07-8, MF:C27H27F2N5O3, MW:507.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (R)-GNE-140 | (R)-GNE-140, CAS:2003234-63-5, MF:C25H23ClN2O3S2, MW:499.04 | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between PGAP2 and Panaroo is not a matter of which tool is universally superior, but which is best suited to a specific research context and dataset.

PGAP2 stands out in scenarios demanding high speed and scalability for analyzing thousands of genomes without sacrificing accuracy. Its strength lies in its quantitative output and efficient algorithms, making it ideal for large-scale population genomics studies where consistent, high-quality annotation can be assumed [2].

Conversely, Panaroo excels in its ability to manage and correct the inherent noise found in genomic datasets, particularly those with fragmented assemblies or annotations from diverse sources. Its graph-based approach provides a more biologically realistic and accurate pan-genome, which is critical for studies focused on accessory genome dynamics, structural variation, or when working with data from multiple sequencing centers [32] [35].

Recommendation: For a rapid, large-scale analysis of a consistently annotated dataset, PGAP2 is an excellent choice. For a more conservative analysis that prioritizes accuracy by correcting for annotation artifacts and fragmentation—especially in mixed-quality datasets—Panaroo is the recommended tool. In practice, running a pilot analysis on a subset of data with both pipelines can provide the clearest guidance for the final, full-scale study.

Comparative genomic analysis is a fundamental methodology in prokaryotic research, enabling scientists to investigate evolutionary relationships, understand pathogenicity, and identify horizontal gene transfer events. The ability to visualize these comparisons is crucial for interpreting complex genomic data and communicating findings effectively. This article provides Application Notes and Protocols for three prominent tools—LoVis4u, ACT, and Easyfig—each offering distinct approaches to genomic visualization for different research scenarios. Framed within the broader context of a thesis on comparative genomics tools, this guide aims to equip researchers with practical methodologies for selecting and implementing appropriate visualization strategies based on their specific analytical needs, whether investigating bacteriophage genomes, conducting detailed pairwise comparisons, or creating publication-ready linear figures.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of LoVis4u, ACT, and Easyfig to facilitate appropriate tool selection.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Genomic Visualization Tools

| Tool Name | Primary Interface | Core Functionality | Output Formats | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LoVis4u [36] [37] | Command-line, Python API | Fast, customizable visualization of multiple loci; identifies core/accessory genes | Publication-ready PDF | High-throughput generation of vector images for many genomic regions |

| ACT (Artemis Comparison Tool) [38] [39] | Graphical User Interface (GUI) | Interactive, detailed pairwise comparison of whole genomes | Screen output, image files | In-depth, base-level analysis of genome rearrangements and differences |

| Easyfig [40] [41] | GUI, Command-line | Linear comparison of multiple genomic loci with BLAST integration | BMP, SVG | Creating clear, linear comparison figures for publications |

LoVis4u: Protocol for High-Throughput Locus Visualization

Application Notes