16S rRNA Gene Sequencing in Microbial Ecology: A Comprehensive Protocol Guide from Basics to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to 16S rRNA gene sequencing for microbial ecology studies, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing in Microbial Ecology: A Comprehensive Protocol Guide from Basics to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to 16S rRNA gene sequencing for microbial ecology studies, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles of 16S rRNA as a phylogenetic marker, detailed methodological protocols from sample collection to data analysis, troubleshooting for common technical challenges, and comparative evaluation of sequencing platforms and bioinformatics tools. The content synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends, including full-length sequencing and advanced denoising algorithms, to enable robust experimental design and accurate interpretation of microbial community data in both environmental and clinical contexts.

Understanding 16S rRNA: The Essential Biomarker for Microbial Phylogeny and Ecology

The 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene is a fundamental genetic marker in microbiology and microbial ecology, serving as a molecular chronometer for deciphering evolutionary relationships among bacteria and archaea [1]. This gene, approximately 1,550 base pairs in length, is universally present in all prokaryotes and contains a unique combination of highly conserved regions and hypervariable regions that provide the necessary signals for phylogenetic classification and taxonomic identification [1] [2]. The conserved regions enable the design of universal PCR primers that can amplify the gene from virtually any bacterial species, while the variable regions accumulate mutations at different rates, creating a signature that can distinguish taxa at various phylogenetic levels, from domain to species [1].

The adoption of 16S rRNA gene sequencing has revolutionized microbial ecology by providing a culture-independent method for profiling complex microbial communities. This approach has revealed that over 99% of microorganisms in many environments cannot be easily cultured using standard laboratory techniques [3]. The gene's structure, with nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) interspersed between conserved segments, makes it ideally suited for high-throughput sequencing technologies that power modern microbiome research [4] [2]. As a result, 16S rRNA gene sequencing has become the gold standard for exploring microbial diversity in diverse habitats, from the human body to environmental ecosystems [3] [5].

Structural Organization of the 16S rRNA Gene

Conserved and Variable Regions

The 16S rRNA gene exhibits a sophisticated architectural pattern of sequence conservation and variation that directly enables its utility in microbial identification and phylogenetic analysis. The conserved regions maintain critical functional elements necessary for the ribosome's protein synthesis machinery, preserving the gene's fundamental biological role across evolutionary time [1] [2]. These conserved stretches, particularly at the beginning of the gene and around position 540 bp or at the end (approximately 1,550 bp), serve as reliable binding sites for universal PCR primers used in amplification for sequencing studies [1].

Interspersed between these conserved areas are nine hypervariable regions (V1 through V9) that demonstrate substantial sequence divergence across different bacterial taxa [4]. These variable regions evolve at different rates, with some showing higher discriminatory power for certain taxonomic groups. For instance, the V1 and V2 regions have demonstrated the highest resolving power for accurately identifying respiratory bacterial taxa from sputum samples, while the V4 region is highly conserved and functionally important in the ribosome [2]. The variable regions range in length and sequence diversity, with the initial 500 bp of the gene (encompassing several variable regions) often containing slightly more diversity per kilobase sequenced compared to the full-length gene [1].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of 16S rRNA Gene Hypervariable Regions

| Region | Approximate Position | Key Characteristics and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| V1-V2 | 69-99 (V1) | Highest resolving power for respiratory microbiota; discriminates Streptococcus species and Staphylococcus aureus from coagulase-negative staphylococci [2]. |

| V3-V4 | ~341-806 | Most commonly targeted region in Illumina-based studies; provides genus-level identification for human gut microbiome dominated by Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes [4] [6]. |

| V4 | - | Highly conserved with functional importance in ribosome; frequently used alone in microbiome studies [2] [5]. |

| V5-V7 | - | Shows compositional similarity to V3-V4 region in respiratory samples [2]. |

| V7-V9 | - | Significantly lower alpha diversity measurements; less commonly used [2]. |

| Full-length (V1-V9) | ~1,550 bp | Enables species-level resolution; requires long-read sequencing technologies (Nanopore, PacBio) [3] [5]. |

Comparative Analysis of Hypervariable Regions

The discriminatory power of different hypervariable regions varies considerably across microbial habitats and taxonomic groups. A comparative study of respiratory samples found that the V1-V2 combination exhibited the highest sensitivity and specificity (AUC 0.736) for identifying respiratory bacterial taxa compared to other region combinations [2]. Alpha diversity metrics also differed significantly between regions, with V1-V2, V3-V4, and V5-V7 showing significantly higher diversity compared to V7-V9 [2].

In gut microbiome studies, the V3-V4 regions have been recognized as the optimal target for amplification because this ecosystem is predominantly characterized by Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes [6]. However, the pursuit of species-level identification has driven increased interest in full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing (spanning V1-V9), as shorter regions generally only permit reliable genus-level classification [3] [6]. While full-length sequencing provides superior resolution, the V3-V4 regions offer practical advantages including reduced costs, higher throughput, and smaller sample size requirements, making them particularly suitable for analyzing low-abundance or contaminated clinical specimens [6].

Applications in Microbial Ecology and Clinical Research

Taxonomic Identification and Biomarker Discovery

The primary application of 16S rRNA gene sequencing in microbial ecology is taxonomic classification of microbial community members. The level of taxonomic resolution achievable depends on several factors, including the specific variable regions targeted and the sequencing technology employed. While full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing facilitates species-level identification, sequencing of the V3-V4 variable regions is generally confined to genus-level identification [6]. However, novel bioinformatics approaches are challenging this limitation by establishing flexible classification thresholds for common gut bacteria, with species-specific thresholds ranging from 80% to 100% similarity, thereby improving species-level classification from V3-V4 data [6].

In clinical research, 16S rRNA gene sequencing has proven particularly valuable for biomarker discovery in disease states. For example, in colorectal cancer (CRC) research, full-length 16S rRNA sequencing using Nanopore technology identified more specific bacterial biomarkers than shorter V3-V4 regions sequenced with Illumina technology [3]. Key CRC biomarkers identified through this approach included Parvimonas micra, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Peptostreptococcus stomatis, Peptostreptococcus anaerobius, Gemella morbillorum, Clostridium perfringens, Bacteroides fragilis, and Sutterella wadsworthensis [3]. The ability to achieve species-level resolution was critical here, as different species within the same genus can display substantial variations in pathogenic potential [6].

Diagnostic Applications in Clinical Microbiology

In clinical diagnostics, 16S rRNA gene PCR and sequencing serves as an important tool for identifying pathogens in challenging infections, particularly when conventional culture methods fail. A retrospective study at Mayo Clinic found that 20% of tests on normally sterile specimens from pediatric patients were positive, with 58% of positive samples coming from culture-negative specimens [7]. Fluid specimens were more than three times as likely to test positive as tissue specimens, with pleural fluid demonstrating the highest positivity rate (50%) [7].

This method has shown particular value in identifying pathogens in patients who have received prior antibacterial therapy, which was associated with a higher likelihood of positive results (p = 0.001) [7]. Among positive tests, 36% revealed polymicrobial infections that might have been missed with conventional methods, highlighting the technique's value in complex clinical cases [7]. The most common bacteria identified as single pathogens were Staphylococcus aureus complex (12%) and Kingella kingae (9%, all from synovial fluid) [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

16S rRNA Gene PCR and Sequencing for Clinical Diagnosis

The Mayo Clinic protocol for 16S rRNA gene testing in clinical diagnostics involves a comprehensive workflow from sample processing to final reporting [7]:

Specimen Processing and DNA Extraction:

- Specimens are processed and bacterial cultures are performed in Clinical Bacteriology Laboratories.

- Isolated bacteria are identified using conventional biochemical methods or matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry.

PCR Amplification and Sequencing Selection:

- The assay involves an up-front real-time PCR assay, reported as negative or submitted for sequencing based on cycle threshold (Ct) value.

- Specimens with Ct values <32 cycles undergo bidirectional Sanger sequencing using an Applied Biosystems 3500xL Genetic Analyzer.

- Specimens with Ct values of 32-34, or <32 with Sanger sequencing that yielded an uninterpretable result, are sent for next-generation sequencing using an Illumina MiSeq System with a 500-cycle v2 nano kit.

- Specimens with Ct values >34 are reported as negative, except if a well-defined melting temperature peak (>0.4) is observed, in which case they are sent for NGS.

Sequence Analysis:

- Pathogenomix software is used for quality control processes and the Pathogenomix PRIME database for sequence analysis.

- The database contains 48,139 curated 16S rRNA gene sequences.

- The processor filters low-quality reads (Q<30) and clusters sequences based on >210-bp length, >100 copies, and 0% variation.

The mean turnaround time for positive tests was 8 days (range 3.2-12.8 days), while negative tests were finalized in approximately 3 days (range 0-6.7 days) [7].

Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing with Oxford Nanopore

For full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing using Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), the following protocol has been demonstrated effective for biomarker discovery in colorectal cancer research [3]:

PCR Amplification:

- The full-length 16S rRNA gene is amplified using primers 27F (AGAGTTTGATYMTGGCTCAG) and 1492R (GGTTACCTTGTTAYGACTT).

- These primers target the beginning and end of the approximately 1,500 bp gene, covering all nine variable regions (V1-V9).

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Amplicons are purified with KAPA HyperPure Beads (Roche).

- Libraries are prepared using the Native Barcoding Kit 96 (SQK-NBD109.96).

- Sequencing is performed on MinION platforms using R10.4.1 flow cells, which provide improved basecalling accuracy.

Basecalling and Taxonomic Analysis:

- Basecalling is performed using Dorado models (fast, hac, and sup).

- Taxonomic classification uses the Emu algorithm, which is specifically designed for analyzing full-length 16S rRNA sequences from ONT data.

- Comparisons can be made against reference databases including SILVA and Emu's Default database.

This approach leverages the long-read capability of Nanopore sequencing to generate complete 16S rRNA gene sequences, enabling more accurate species-level identification compared to short-read technologies that target only partial gene regions [3].

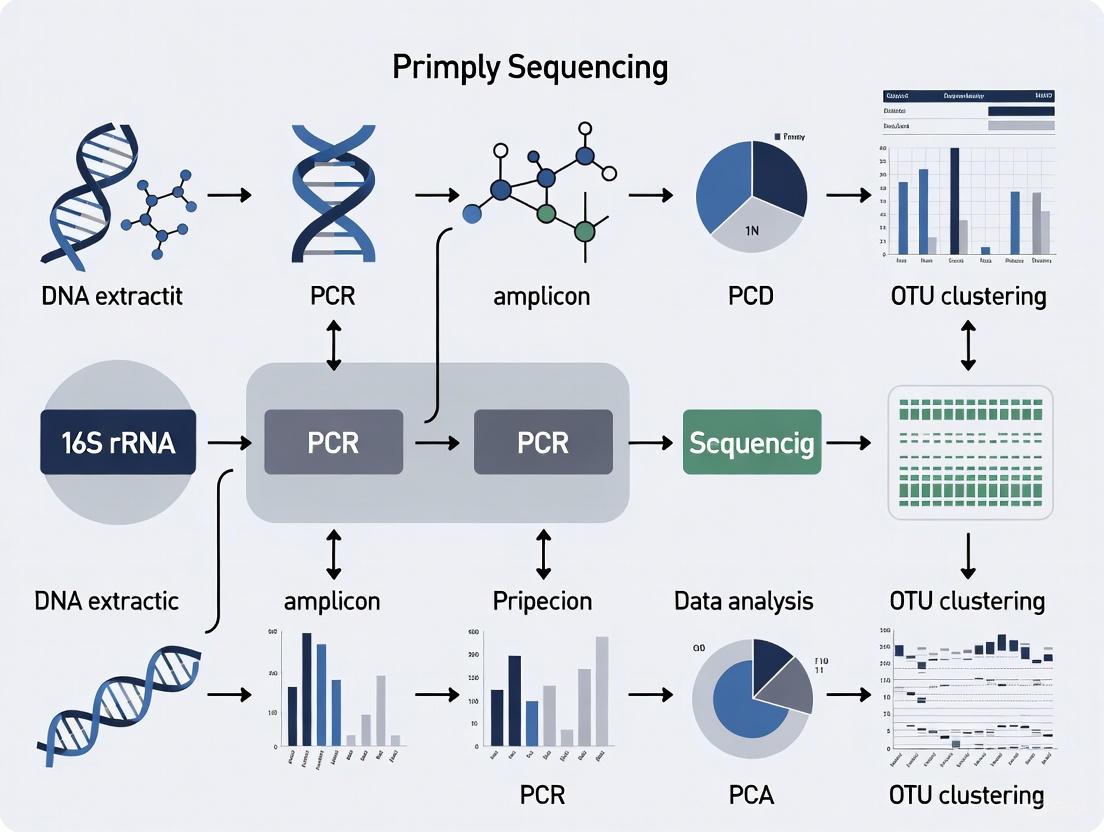

Diagram Title: 16S rRNA Gene Analysis Workflow

Short-Read Multi-Region Sequencing with Illumina

For researchers requiring species-level resolution while maintaining the cost-effectiveness of Illumina sequencing, a protocol using multiple variable regions with the xGen 16S Amplicon Panel v2 kits has been developed [4]:

Library Preparation:

- The xGen 16S Amplicon Panel v2 kits are used to amplify all nine variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene.

- Sequencing is performed on an Illumina MiSeq platform.

- Mock cells and mock DNA for known bacterial species are included as extraction and sequencing controls.

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- The Swift Normalase Amplicon Panels APP for Python 3 (SNAPP-py3) pipeline is used for analysis.

- Within-run and between-run replicate samples are incorporated to assess reproducibility.

- Technical replicate samples sequenced on the same plate (within-run) or across different sequencing plates and runs (between-run) are compared.

This approach demonstrates that accurate species-level resolution can be achieved with short-read sequencing by simultaneously targeting multiple variable regions, provided that appropriate bioinformatic processing is applied [4].

Comparative Performance of Sequencing Technologies and Regions

Sequencing Platform Comparison

The choice of sequencing platform significantly impacts the resolution and accuracy of 16S rRNA gene analysis. Third-generation sequencing platforms (PacBio and Oxford Nanopore) offer advantages in taxonomic resolution due to their ability to sequence the full-length 16S rRNA gene, while second-generation platforms (Illumina) provide higher throughput and lower cost but are limited to partial gene regions [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Sequencing Platforms for 16S rRNA Gene Analysis

| Platform | Read Length | Target Regions | Typical Taxonomic Resolution | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Short-read (100-400 bp) | Single or multiple variable regions (e.g., V3-V4, V4) | Genus-level [6] | High throughput, low cost per sample, well-established protocols [4] | Limited to partial gene regions, ambiguous taxonomic assignments [5] |

| PacBio | Long-read (full-length) | Full-length 16S (V1-V9) | Species-level [5] | High accuracy (>99.9%) with circular consensus sequencing [5] | Higher cost, lower throughput [5] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Long-read (full-length) | Full-length 16S (V1-V9) | Species-level [3] | Real-time sequencing, low initial equipment cost, portable [3] | Higher error rates, though improved with R10.4.1 chemistry [3] [5] |

Recent evaluations of Nanopore's R10.4.1 chemistry and improved basecalling models have demonstrated significantly improved accuracy, with Q-scores approaching Q28 (~99.84% base accuracy) in some reports [5]. In soil microbiome studies, ONT and PacBio provided comparable bacterial diversity assessments, with PacBio showing slightly higher efficiency in detecting low-abundance taxa [5]. Despite differences in sequencing accuracy, ONT produced results that closely matched those of PacBio, suggesting that its inherent sequencing errors do not significantly affect the interpretation of well-represented taxa [5].

Bioinformatics Processing Approaches

The bioinformatic processing of 16S rRNA gene sequencing data typically employs one of two approaches: clustering-based Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or denoising-based Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). A comprehensive benchmarking analysis using complex mock communities revealed that ASV algorithms (led by DADA2) produced consistent output but suffered from over-splitting, while OTU algorithms (led by UPARSE) achieved clusters with lower errors but with more over-merging [8].

The traditional OTU approach clusters sequences based on a fixed similarity threshold (typically 97%), assuming that sequence variants within this threshold represent sequencing errors of a single biological sequence [8]. In contrast, ASV methods employ different statistical models to discriminate real biological sequences from spurious ones, providing single-nucleotide resolution [8]. The denoising approach offers greater consistency across studies but can generate multiple ASVs for non-identical 16S rRNA gene copies within the same strain [8].

The optimal similarity threshold for taxonomic classification varies across the tree of life. Under the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) framework, achieving species-level resolution requires clustering 16S sequences at a divergence threshold of around 0.01 (99% identity), while genus-level resolution requires thresholds of 0.04-0.08 (92-96% identity) [9]. However, these optimal thresholds vary significantly across different bacterial branches, highlighting the limitations of using a fixed divergence threshold for all taxa [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for 16S rRNA Gene Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples and Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Primers | Amplify 16S rRNA gene from diverse taxa | 27F/1492R for full-length [5]; 341F/806R for V3-V4 [6]; region-specific primers for targeted amplification |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality microbial DNA | Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Microprep kit for environmental samples [5]; host DNA depletion methods for host-associated microbiomes |

| PCR Amplification Kits | Robust amplification of target regions | Kits with high fidelity polymerase to reduce amplification errors; mock community controls for quantification [4] |

| Sequencing Kits | Platform-specific library preparation | xGen 16S Amplicon Panel v2 for Illumina [4]; SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 for PacBio [5]; Native Barcoding Kit for Nanopore [5] |

| Reference Databases | Taxonomic classification of sequences | SILVA [3] [9], GTDB [9], Emu's Default database [3], specialized databases (e.g., 16SGOSeq for oral microbiome [10]) |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Processing and analyzing sequence data | DADA2 [8], Deblur [2] [8], UNOISE3 [8] for denoising; UPARSE [8] for clustering; Emu for Nanopore data [3]; QIIME2 [3] |

| Enrofloxacin | Enrofloxacin, CAS:93106-60-6, MF:C19H22FN3O3, MW:359.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Gilvocarcin V | Gilvocarcin V | Gilvocarcin V is a potent antitumor antibiotic for research use only (RUO). It inhibits DNA synthesis and causes DNA cleavage. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Specialized niche-specific databases have been shown to improve taxonomic classification accuracy compared to general databases. For example, the 16SGOSeq database provides curated 16S rRNA gene sequences specifically for oral bacteria and archaea, addressing the limitation that genomes and 16S rRNA gene sequences in a given species may vary among environments [10]. Similarly, the expanded Human Oral Microbiome Database (eHOMD) serves as an oral-specific reference [10]. The use of such environment-specific databases improves classification accuracy by aligning reference sequences more closely with the microbial communities under investigation [10].

Diagram Title: 16S rRNA Gene Structure and Analysis

The 16S rRNA gene remains an indispensable tool in microbial ecology and clinical microbiology, with its unique structure of conserved and variable regions providing the foundation for taxonomic classification and phylogenetic analysis. While traditional short-read sequencing of partial gene regions continues to offer a cost-effective approach for genus-level community profiling, technological advances in long-read sequencing are increasingly enabling species-level resolution through full-length 16S rRNA gene analysis [3] [5]. The choice of specific variable regions, sequencing platforms, and bioinformatic processing methods should be guided by the specific research question, target environment, and required taxonomic resolution [2]. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve and reference databases expand, 16S rRNA gene sequencing will maintain its central role in exploring the microbial world and understanding its profound implications for human health and ecosystem functioning.

Why 16S rRNA is a Universal Bacterial and Archaeal Marker

The 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene has served as the foundational molecular marker for microbial ecology and identification for decades, providing a universal framework for classifying and understanding the diversity of Bacteria and Archaea [11] [12]. Its role is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who require accurate taxonomic characterization of microbial communities from diverse environments, ranging from human guts to extreme ecosystems. The gene's enduring utility stems from a unique combination of evolutionary and practical properties: it is present in all prokaryotes, contains a mosaic of evolutionarily conserved and variable regions, and its function—essential for protein synthesis—has remained unchanged over time, making it a reliable molecular chronometer [11] [13]. This application note details the theoretical underpinnings, practical protocols, and key applications of 16S rRNA gene sequencing, providing a comprehensive resource for its use in modern microbial research.

Fundamental Properties of the 16S rRNA Gene

The 16S rRNA gene possesses a set of unique characteristics that solidify its role as a universal marker.

Universal Distribution and Functional Constancy

The 16S rRNA gene is a subunit of the prokaryotic ribosome and is found in all bacterial and archaeal cells, often as part of a multigene family or operon [11] [14]. Its function in protein synthesis is fundamental and has not changed over evolutionary time, meaning that random sequence changes provide a more accurate measure of evolutionary divergence [11]. This functional constancy ensures it is a valid molecular chronometer for assessing phylogenetic relationships.

Ideal Gene Structure for Phylogenetics

The gene is approximately 1,500 base pairs long, providing sufficient sequence length for robust informatics analysis [11] [14]. Its structure comprises nine variable regions (V1-V9), which are interspersed between conserved regions [14]. The variable regions provide the signature for genus- or species-level classification, while the conserved regions enable the design of universal PCR primers that can amplify the gene from virtually any bacterium or archaeon [13].

Expansive and Curated Reference Databases

Decades of research have resulted in extensive, curated databases of 16S rRNA gene sequences, such as Greengenes, SILVA, and RDP [13]. These repositories allow for the comparison of newly generated sequences from unknown isolates or complex communities against a vast backbone of taxonomically classified sequences, enabling rapid identification and ecological interpretation.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the 16S rRNA Gene as a Phylogenetic Marker

| Characteristic | Description | Implication for Microbial Ecology |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Distribution | Found in all Bacteria and Archaea [14] | Allows for comprehensive profiling of entire prokaryotic communities. |

| Functional Constancy | Role in protein synthesis is unchanged over time [11] | Sequence changes act as a molecular clock for measuring evolutionary distance. |

| Mosaic Structure | Nine hypervariable regions flanked by conserved regions [14] | Conserved regions enable universal amplification; variable regions enable taxonomic discrimination. |

| Adequate Length | ~1,500 base pairs [11] | Provides sufficient information for robust phylogenetic analysis. |

| Large Reference Databases | Greengenes, SILVA, RDP | Enables classification of sequences from unknown organisms and environments. |

Experimental Protocols for 16S rRNA Gene Analysis

Standard Laboratory Workflow for Full-Length 16S Amplicon Sequencing

This protocol is adapted for full-length 16S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing, suitable for high-resolution taxonomic profiling [15].

1. DNA Extraction:

- Use a standardized kit (e.g., DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit for environmental samples) to ensure lysis of a broad range of microbial cells.

- Incorporate a bead-beating step (e.g., two rounds of 45 seconds at high speed) to effectively lyse Gram-positive bacteria [15].

- Quantify extracted DNA using a fluorometric assay (e.g., Qubit).

2. PCR Amplification of the 16S rRNA Gene:

- Use primers targeting conserved regions to amplify the full-length gene. A common primer pair is 27F (5'-AGRGTTTGATYMTGGCTCAG-3') and 1492R (5'-RGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3') [15].

- Employ a high-fidelity hot-start polymerase master mix (e.g., KAPA HiFi HotStart) to minimize PCR errors.

- PCR Cycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 3 minutes.

- 25-35 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 98°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing: 55°C for 45 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 90 seconds.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 minutes.

3. Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Clean up PCR products using solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads (e.g., AMPure XP).

- For Nanopore sequencing (e.g., with the 16S Barcoding Kit), normalize and pool barcoded libraries. Sequence on a MinION or GridION platform with a Flongle or MinION flow cell [15].

- For Illumina sequencing, a similar approach can be used, typically targeting shorter, specific variable regions (e.g., V3-V4).

The SituSeq Protocol for Remote and Rapid Analysis

The SituSeq protocol enables offline, portable sequencing and analysis, ideal for fieldwork or point-of-care diagnostics [15].

- Portable DNA Extraction & PCR: Perform steps 1 and 2 above using portable equipment.

- Sequencing on a MinION: Use a laptop-powered MinION sequencer for sequencing.

- Offline Bioinformatic Analysis: Utilize the SituSeq pipeline on a standard laptop with a pre-loaded database. The entire process—from DNA extraction to data visualization—can be completed in less than 8 hours, with initial results available in less than 2 hours after sequencing begins [15].

Performance and Quantitative Analysis

The performance of 16S rRNA gene sequencing is well-established through systematic evaluations.

Identification Accuracy

A large-scale study comparing 16S rRNA gene sequencing to clinical identification methods for 617 isolates across 30 pathogenic species demonstrated high concordance. The study utilized a Naïve Bayes classifier for species-level identification, revealing a genus-level concordance of 96% and a species-level concordance of 87.5% [13]. This confirms the method's high reliability for broad bacterial identification.

Resolution and Limitations

While powerful, 16S rRNA gene sequencing has limitations in resolution. A similarity threshold of 97% is often used as a rule-of-thumb for demarcating species, but this is not universal [11]. Some species share identical or nearly identical 16S rRNA sequences despite clear genomic distinction. For example, the type strains of Bacillus globisporus and B. psychrophilus share >99.5% 16S sequence similarity but exhibit only 23-50% relatedness by DNA-DNA hybridization, the historical gold standard for species definition [11]. Table 2 outlines the typical identification success rates and Table 3 lists genera where 16S resolution is problematic.

Table 2: Performance of 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing for Bacterial Identification

| Study Focus | Number of Strains | Genus-Level ID Rate | Species-Level ID Rate | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unidentified/Ambiguous Isolates [11] | Various Studies | >90% | 65% to 83% | Novel taxa; shared sequences between species. |

| Clinically Relevant Pathogens [13] | 617 | 96% | 87.5% | Probable misidentification with culture-based methods. |

| Routine Clinical Isolates [11] | Various Studies | N/A | 62% to 91% | Incomplete databases; non-distinguishable groups. |

Table 3: Bacterial Genera with Known 16S rRNA Gene Resolution Challenges [11]

| Genus | Example Species with Poor Resolution |

|---|---|

| Bacillus | B. anthracis, B. cereus, B. globisporus, B. psychrophilus |

| Streptococcus | S. mitis, S. oralis, S. pneumoniae |

| Neisseria | N. cinerea, N. meningitidis |

| Burkholderia | B. pseudomallei, B. thailandensis |

| Enterobacter | E. cloacae (complex of multiple genomovars) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents and Kits for 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

| Item | Function | Example Product / Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Lyses microbial cells and purifies genomic DNA from complex samples. | DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) [15] |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies the 16S rRNA gene with low error rate during PCR. | KAPA HiFi HotStart Master Mix (Roche) [15] |

| Universal 16S Primers | Binds conserved regions to amplify the 16S gene from diverse taxa. | 27F (AGRGTTTGATYMTGGCTCAG) / 1492R (RGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT) [15] |

| Library Prep Kit | Prepares amplicons for sequencing by adding adapters and barcodes. | 16S Barcoding Kit (SQK-RAB204, Oxford Nanopore Technologies) [15] |

| Sequence Clean-up Beads | Purifies and size-selects PCR products and final sequencing libraries. | AMPure XP Beads (Beckman Coulter) [15] |

| Bioinformatics Database | Provides a curated reference for taxonomic classification of sequences. | GreenGenes, SILVA [14] [16] |

| Ginkgoneolic acid | Ginkgoneolic Acid (C13:0) - CAS 20261-38-5 - For Research Use | Ginkgoneolic acid, a Ginkgo biloba phenol, is for research into anticancer, antimicrobial, and antidiabetic mechanisms. RUO. Not for human consumption. |

| Ginsenoside Rg3 | Ginsenoside Rg3 | Explore Ginsenoside Rg3 for RUO. This ginsenoside is a key reagent for studying anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant mechanisms. For Research Use Only. |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the properties of the 16S rRNA gene and its resulting applications in research and diagnostics.

Diagram 1: From 16S rRNA properties to research applications.

The experimental workflow for obtaining and analyzing 16S rRNA data, from sample collection to biological insight, is outlined below.

Diagram 2: The 16S rRNA gene sequencing and analysis workflow.

Key Applications in Microbial Ecology and Drug Development

Application Notes: The Versatility of 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing has become a cornerstone technique in molecular microbiology, enabling culture-free analysis of complex microbial communities. The method exploits the genetic characteristics of the 16S rRNA gene, which contains nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) interspersed between conserved sequences. This structure provides species-specific signatures that allow for phylogenetic classification and identification [14].

The applications of this technology span diverse fields, from foundational ecology to clinical drug development, by providing a rapid, cost-effective, and high-precision method for bacterial identification and classification [17].

Applications in Microbial Ecology

In environmental sciences, 16S rRNA sequencing is vital for characterizing microbial diversity and understanding ecosystem function.

- Soil Health and Bioremediation: Sequencing is used to monitor changes in soil microbial communities, providing critical data for soil management and rehabilitation strategies. Analysis of ex situ microbial changes can associate soil samples with their correct habitat with 99% accuracy, even with samples as small as 1 mg, highlighting its forensic utility in environmental assessment [18]. Furthermore, 16S rRNA sequencing can screen for microbial strains capable of degrading industrial waste, facilitating resource recycling and environmental protection [17] [19].

- Ecological Monitoring and Diversity Studies: The technique allows ecologists to compare microbial structures across different ecosystems (e.g., soil, water, air) and identify the roles of specific microbial communities. By monitoring temporal changes, scientists can assess the impact of disruptive factors like environmental pollution on ecosystem health and stability [17].

Applications in Drug Development

The role of 16S rRNA sequencing in pharmaceutical research is increasingly prominent, particularly in understanding microbiome-drug interactions.

- Drug Safety and Metabolism: 16S rRNA sequencing provides insights into a patient's microbial community, which can help predict drug metabolism and side effects. For instance, integrated 16S rRNA sequencing and metabolomics analyses have identified specific microbial genera (e.g., Blautia, Ralstonia, and Veillonella) correlated with biomarkers for drug-induced liver injury, offering potential avenues for therapeutic advancement and safety evaluation [17].

- Biomarker Discovery for Diagnostics: Sequencing facilitates the discovery of microbial markers associated with diseases, providing targets for new drug development. For example, comparing the blood microbiome of Parkinson's disease patients and healthy individuals via 16S rRNA sequencing revealed significant associations between certain genera (Paludibacter and Saccharofermentans) and the disease [17]. Full-length 16S sequencing (V1-V9) with Oxford Nanopore Technologies has been shown to increase species-level resolution, enabling the identification of more precise bacterial biomarkers for conditions like colorectal cancer than shorter-read methods [3].

- Impact of Pharmaceuticals on Microbiomes: 16S rRNA sequencing is employed to assess the impact of pharmaceutical contamination on environmental and host-associated microbiomes. Studies confirm that pharmaceuticals, including antibiotics and antidepressants, induce significant shifts in microbial community structure, reducing alpha diversity and enriching for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes [19].

Table 1: Key Applications of 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

| Field | Specific Application | Utility and Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial Ecology | Soil health assessment & bioremediation | Serves as reference for soil management; screens strains for waste degradation [17] [19]. |

| Ecological monitoring & diversity studies | Compares microbial structures across ecosystems; assesses impact of environmental disruptors [17]. | |

| Drug Development | Drug safety & metabolism | Predicts drug metabolism and side effects by profiling patient microbiomes [17]. |

| Biomarker discovery | Identifies microbial markers linked to diseases (e.g., Parkinson's, colorectal cancer) for diagnostic and therapeutic development [17] [3]. | |

| Toxicological impact assessment | Evaluates how pharmaceuticals alter microbial communities and enrich for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes [19]. | |

| Forensic Science | Individual identification | Uses unique microbial "fingerprints" from skin, oral, or soil microbiomes for identification when human DNA is unavailable [18] [17]. |

| Industrial Microbiology | Fermentation optimization & strain screening | Monitors microbial dynamics during fermentation to improve product yield and quality [17]. |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed methodology for full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing using Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), which provides superior species-level resolution compared to short-read sequencing of partial gene regions [3].

Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing with Oxford Nanopore Technology

Principle: This protocol uses long-read nanopore sequencing to generate ~1,500 bp amplicons spanning the V1-V9 regions of the 16S rRNA gene. This full-length sequence information allows for more accurate taxonomic classification down to the species level [20] [21] [3].

Diagram 1: Full-length 16S rRNA sequencing workflow

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ONT 16S rRNA Sequencing

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from samples. | QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (for fecal samples) [20]. |

| 16S Primers | Amplification of the full-length ~1500 bp 16S rRNA gene. | 27F (5'-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3') and 1492R (5'-CGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3') [21]. |

| PCR Master Mix | Amplification of target gene with high fidelity. | LongAmp Hot Start Taq 2X Master Mix [20] [21]. |

| ONT Barcoding Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries with sample barcodes for multiplexing. | 16S Barcoding Kit (e.g., SQK-16S114.24) [20]. |

| Flow Cell | Platform for nanopore-based sequencing. | MinION Flow Cell (R10.4.1) [20] [3]. |

| Basecaller Software | Translates raw electrical signals into nucleotide sequences. | Dorado (using 'hac' or 'sup' models for high accuracy) [3]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol

DNA Extraction:

- Collect sample (e.g., 250 mg of fecal material) in a sterile tube. Samples may be stored at -80°C until processing.

- Extract genomic DNA using a dedicated kit, such as the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit, following the manufacturer's instructions. Homogenize samples using a bead-beater (e.g., FastPrep-24 at 6.5 m/s for 1 minute, repeated twice with cooling intervals) [20].

- Elute DNA in 100 µL of elution buffer and measure concentration using a microvolume spectrophotometer.

Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Amplification:

- Prepare PCR reactions with:

- 2 µL primer mix (400 nM final concentration of forward and reverse primers).

- 1 ng of extracted DNA.

- 12.5 µL LongAmp Hot Start Taq 2X Master Mix.

- Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 25 µL.

- Perform amplification in a thermal cycler with the following settings [21]:

- 1 cycle: 1 min at 94°C (polymerase activation).

- 15-25 cycles*: 20 s at 94°C (denaturation), 30 s at 50-52°C (annealing), 90 s at 65°C (extension).

- 1 cycle: 3 min at 65°C (final extension).

- Note: The number of PCR cycles is critical. Elevated cycles (e.g., >25) can introduce significant PCR bias. Optimize to use the minimum number of cycles required for sufficient yield [21].

- Prepare PCR reactions with:

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Purify the PCR amplicons using SPRIselect magnetic beads [21].

- Prepare the sequencing library using the ONT 16S Barcoding Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions [20].

- Load the prepared library onto a MinION R10.4.1 flow cell.

- Start sequencing run using the MinKNOW software, selecting the appropriate sequencing kit (SQK-16S114.24) and basecalling options [20].

Bioinformatic Analysis Protocol for Species-Level Classification

Principle: This protocol uses the Emu taxonomy assignment tool to leverage the full-length 16S rRNA sequences, overcoming sequencing errors and providing species-level community profiles [20] [3].

Diagram 2: Bioinformatic analysis workflow with Emu

- Computer: A standard computer is required; 16 GB of RAM is recommended, though more complex datasets may require increased memory [20].

- Command Line Interface: A Unix or Linux system is assumed for the following steps.

- Software:

Step-by-Step Analysis Protocol

Environment Setup:

- Download the default Emu database and set the environment variable

EMU_DATABASE_DIRto its location [20]. - Install Emu using bioconda.

- Download the default Emu database and set the environment variable

Taxonomic Profiling:

- Run Emu on a FASTQ file from a single barcode using the command:

- Repeat this command for all samples in the study [20].

Output Interpretation:

- Emu generates a

_rel-abundance.tsvfile containing the estimated species relative abundance for the sample [20]. - Critical Parameter Note: The choice of reference database is crucial. The Emu default database may identify more species but can sometimes overconfidently classify an unknown species as the closest known match. The SILVA database is another common option, though it may report lower diversity [3].

- Emu generates a

Technical Validation and Optimization

Robust application of this protocol requires attention to critical parameters that influence data quality and taxonomic resolution.

Table 3: Optimization Parameters for 16S rRNA Sequencing

| Parameter | Impact on Results | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Region | Taxonomic resolution. Short reads (e.g., V4) cannot achieve the resolution of the full-length (V1-V9) gene [22]. | Use full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing (e.g., ONT, PacBio) for species- and strain-level analysis [22] [3]. |

| PCR Cycle Number | Introduces PCR bias and alters community composition representation [21]. | Use the minimum number of PCR cycles necessary for library preparation (e.g., 15-25 cycles) [21]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipeline | Affects taxonomic assignment accuracy and diversity metrics. Different tools can yield dramatically different community compositions [23]. | For full-length ONT reads, use tools like Emu designed for its error profile [20] [3]. QIIME2 (with DADA2) is a strong performer for short-read Illumina data [23]. |

| Reference Database | Directly determines which taxa can be identified. Different databases have varying coverage and curation [3]. | Select based on study goals. Emu's default database may offer greater specificity, but SILVA is a well-curated alternative. Validate findings with mock communities [3]. |

Advantages and Limitations of Culture-Free Microbial Analysis

Culture-free microbial analysis represents a paradigm shift in microbial ecology, moving beyond traditional culture-based techniques to directly examine genetic material from complex samples. These methods, particularly those leveraging 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing, have revolutionized our ability to characterize microbial communities, including the vast majority of bacteria that are difficult or impossible to cultivate in the laboratory [24]. This application note examines the technical advantages and limitations of these powerful tools, providing structured protocols and resources to guide researchers and drug development professionals in implementing these approaches within microbial ecology research.

Advantages of Culture-Free Analysis

Expanded Detection Capabilities

Culture-independent methods fundamentally overcome the most significant limitation of traditional culturing: the inability to grow most environmental and clinical bacteria in the laboratory. It is estimated that over 99% of microbial species remain undiscovered, largely due to cultivation challenges [3]. By bypassing cultivation, these techniques provide a more comprehensive view of microbial diversity.

- Detection of Unculturable Organisms: 16S rRNA gene sequencing identified bacteria in 95.7% (44/46) of bronchoalveolar lavage specimens from a respiratory study, significantly outperforming culture which detected bacteria in only 80.4% (37/46) of the same specimens [25].

- Revealing Hidden Diversity: In freshwater lake studies, metagenomic sequencing identified 1.5 times as many phyla and approximately 10 times as many genera compared to 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, which itself far exceeds culture capabilities [26].

Speed and Workflow Efficiency

Culture-free methods dramatically reduce the time required for microbial analysis, from weeks to days or even hours.

- Rapid Turnaround: The Molecular Bacterial Load (MBL) assay for Mycobacterium tuberculosis provides results in real-time without the 3-5 week incubation required for culture on solid agar [27].

- High-Throughput Capacity: Next-generation sequencing platforms enable simultaneous multiplexing of several hundred samples in a single run, vastly increasing processing capacity [24].

Comprehensive Community Analysis

These methods enable detailed study of complete microbial community structures and dynamics, rather than focusing on individual, culturable species.

- Biomarker Discovery: Full-length 16S rRNA sequencing with Nanopore technology has identified specific bacterial biomarkers for colorectal cancer, including Parvimonas micra, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Bacteroides fragilis, with machine learning prediction achieving an AUC of 0.87 [3].

- Treatment Monitoring: The MBL assay accurately tracks bacterial load decline during tuberculosis treatment, correlating well with colony-forming unit counts while additionally detecting differentially culturable sub-populations missed by solid culture [27].

Table 1: Key Advantages of Culture-Free Microbial Analysis

| Advantage | Technical Benefit | Research Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Expanded Detection | Identifies viable but non-culturable (VBNC) and fastidious organisms | More complete community diversity assessment |

| Speed | Reduction from weeks to days/hours for results | Faster clinical decision-making and research outcomes |

| Sensitivity | Detection of low-abundance community members | Identification of rare taxa and subtle population shifts |

| Quantification | Real-time tracking of bacterial load (e.g., MBL assay) | Accurate monitoring of treatment efficacy and community dynamics |

| Standardization | Reduced variability from cultivation steps | Improved reproducibility across laboratories and studies |

Limitations and Technical Challenges

Resolution and Identification Constraints

While powerful, culture-free methods face inherent limitations in taxonomic resolution and identification accuracy.

- Species-Level Identification: Short-read sequencing of partial 16S rRNA gene regions (e.g., V3-V4) typically provides genus-level identification, with full-length sequencing required for consistent species-level resolution [3] [6].

- Database Dependencies: Taxonomic assignment accuracy is limited by reference database quality and completeness. Traditional databases suffer from inconsistent nomenclature, non-uniform sequence lengths, and insufficient coverage of non-cultivable strains [6].

Technical and Analytical Complexities

Implementation of culture-free methods requires sophisticated instrumentation, bioinformatics expertise, and careful experimental design.

- Error Rates and Biases: Nanopore sequencing, while enabling full-length 16S analysis, has higher error rates compared to Illumina platforms, affecting taxonomic classification accuracy [3].

- PCR and Selection Biases: Amplification of 16S rRNA gene regions introduces primer-specific biases, while different variable region selections can yield different community representations [26].

Resource and Infrastructure Requirements

The transition from traditional methods requires significant investment in equipment, infrastructure, and technical training.

- Cost Considerations: Middle-income countries face challenges in procuring costly equipment, maintaining platforms, developing laboratory infrastructure, and training technical expertise [24].

- Bioinformatics Burden: Data analysis requires specialized computational skills and resources, creating bottlenecks for laboratories without dedicated bioinformatics support [24].

Table 2: Key Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

| Limitation | Technical Challenge | Mitigation Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Resolution | Variable regions offer different classification power; species-level ID challenging | Use full-length 16S sequencing; implement flexible classification thresholds [6] |

| Database Limitations | Incomplete references; inconsistent nomenclature | Custom database construction; integration of multiple reference sources [6] |

| Technical Variability | PCR/sequencing biases affect reproducibility | Standardized protocols; multiple replicates; spike-in controls [26] |

| Cost and Infrastructure | High initial investment; specialized expertise required | Leverage core facilities; collaborative partnerships; gradual implementation |

| Data Complexity | Bioinformatics expertise required for analysis | User-friendly pipelines (e.g., asvtax); training programs; computational collaborations |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Water Sample Processing for Bacterial DNA Extraction

This protocol adapts methods from systematic reviews of water filtration and DNA extraction for culture-free analysis [28].

Sampling and Filtration

- Sample Collection: Collect water in sterile containers (polypropylene or glass). Common volumes range from 100-1000 mL for drinking water to >10,000 mL for ultrapure waters with low bacterial load [28].

- Filtration Apparatus: Use sterile filtration units with membrane filters. Polyethersulfone (PES) membranes with 0.22 µm pore size are most commonly reported for bacterial capture [28].

- Processing Conditions: Process samples immediately or preserve on ice for transport. For DNA preservation, filters can be stored at -80°C in preservation buffers.

DNA Extraction and Purification

- Cell Lysis: Employ enzymatic pretreatment using proteinase K (1 mg/mL), lysozyme (1 mg/mL), or lysostaphin for difficult-to-lyse bacteria. Combine with physical methods including bead-beating, freeze-thaw cycles, or sonication [28].

- DNA Extraction: Use commercial kits (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy PowerWater) or in-house protocols (e.g., phenol-chloroform extraction). Include negative controls to monitor contamination.

- DNA Quantification: Assess DNA quality and quantity using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit High-Sensitivity Fluorometer). The expected yield varies significantly with sample type and bacterial load [29].

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Workflow

This protocol outlines the standard workflow for bacterial community analysis using 16S rRNA gene sequencing [24].

Library Preparation

- Target Amplification: Amplify hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene using region-specific primers. The V3-V4 regions (341F-806R) offer a balance between length and discriminatory power, while full-length V1-V9 regions provide superior species resolution [3] [6].

- PCR Conditions: Use 25-30 amplification cycles with touchdown protocols to reduce spurious amplification: Denaturation at 95°C for 20s, annealing from 60°C to 50°C (decreasing 1°C every 2 cycles), and extension at 72°C for 45s [25].

- Library Normalization: Quantify and normalize amplicons using fluorometric methods before pooling libraries in equimolar ratios.

Sequencing and Analysis

- Platform Selection: Choose based on resolution needs: Illumina MiSeq for short-read (V3-V4) with high accuracy; Oxford Nanopore (R10.4.1 chemistry) or PacBio for full-length 16S with species-level resolution [3].

- Bioinformatic Processing: Use specialized pipelines: DADA2 or QIIME2 for Illumina data; Emu or NanoClust for Nanopore data [3].

- Taxonomic Assignment: Classify sequences against curated databases (SILVA, RDP, or custom databases) using tools like SINTAX or the asvtax pipeline with flexible thresholds [6].

Diagram 1: Culture-Free Analysis Workflow. This diagram illustrates the standard workflow for culture-free microbial analysis, from sample collection to community analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Culture-Free Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane Filters (0.22µm PES) | Bacterial capture from liquid samples | Polyethersulfone (PES) most common; 0.22µm pore size optimal for bacterial retention [28] |

| DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., DNeasy PowerWater) | Nucleic acid purification from environmental samples | Optimized for difficult-to-lyse environmental bacteria; includes inhibitors removal [28] |

| 16S rRNA Primers (341F-806R) | Amplification of V3-V4 hypervariable regions | Balance between amplicon length and taxonomic resolution; widely used for Illumina [6] |

| PCR Reagents (including high-fidelity polymerase) | Target amplification with minimal bias | Reduced error rate essential for accurate sequence variant calling [24] |

| Quantification Kits (e.g., Qubit HS DNA) | Accurate DNA quantification | Fluorometric methods preferred over spectrophotometry for sensitivity with low biomass [29] |

| Library Prep Kits (platform-specific) | Sequencing library preparation | Tailored to sequencing platform (Illumina, Nanopore, PacBio) [24] |

| Positive Controls (mock communities) | Process validation and quality control | Defined mixtures of bacterial DNA assess technical variability and sensitivity [26] |

| Preservation Buffers (e.g., RNA/DNA stabilizers) | Sample stabilization before processing | Critical for field sampling; prevents nucleic acid degradation [29] |

| Gitogenin | Gitogenin, CAS:511-96-6, MF:C27H44O4, MW:432.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Glaucarubin | Glaucarubin, CAS:1448-23-3, MF:C25H36O10, MW:496.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Culture-free microbial analysis represents a transformative approach in microbial ecology, offering unprecedented capabilities for comprehensive community characterization while presenting significant technical and analytical challenges. The advantages of expanded detection, reduced turnaround time, and community-level insights must be balanced against limitations in taxonomic resolution, technical complexity, and infrastructure requirements. As methodologies continue to advance—particularly through full-length 16S sequencing, improved bioinformatics pipelines, and customized databases—these approaches will increasingly enable researchers and drug development professionals to decipher complex microbial communities with greater accuracy and biological relevance. Successful implementation requires careful consideration of methodological choices throughout the workflow, from sample collection to computational analysis, to ensure robust and interpretable results.

16S rRNA Sequencing Workflow: From Sample Collection to Data Generation

In microbial ecology research, the accuracy of 16S rRNA gene sequencing is fundamentally dependent on the initial steps of sample collection and preservation. The integrity of microbial community structure can be compromised by improper handling, rendering even the most sophisticated downstream analyses unreliable. This protocol outlines evidence-based best practices for collecting and preserving diverse sample types to minimize technical bias and preserve true biological signatures for robust microbial ecology studies [30] [31].

General Principles for Sample Integrity

Effective microbiome research requires maintaining microbial community composition from the moment of collection until nucleic acid extraction. Key principles apply across all sample types:

- Minimize Contamination: For low-biomass samples, use single-use DNA-free collection materials, decontaminate surfaces with sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or UV-C light, and wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) including gloves, masks, and clean suits to reduce contamination from human operators and the environment [31].

- Control Temperature and Time: Limit sample exposure to ambient temperature. For many sample types, freeze at -80°C immediately or within 24 hours is considered the "gold standard." When immediate freezing is impossible, use appropriate preservation buffers to stabilize microbial communities [30] [32].

- Standardize Procedures: Consistent methodology across samples is crucial for comparative analyses. Standardize sample quantity, collection technique, and handling procedures to minimize batch effects [30] [33].

- Implement Controls: Include field blanks (e.g., empty collection vessels, exposed swabs) and extraction negatives to identify contamination sources. These controls are essential for distinguishing environmental contaminants from true signals, particularly in low-biomass studies [31].

Sample Type-Specific Protocols

Human Stool Samples

Collection Protocol:

- Collect fresh stool in sterile, DNA-free containers.

- For self-collection, provide subjects with pre-filled containers containing preservation buffer when cold chain transport is not feasible [30].

- Aliquot samples to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

- Ideally, immediately freeze at -80°C. Alternative preservation methods include:

- Preservation Buffers: Use commercial preservatives like Norgen Biotek Stool Nucleic Acid Preservative or OMNIgene.GUT for room temperature storage for up to 7 days [30].

- Ethanol: 95% ethanol can preserve bacterial DNA but may yield lower DNA quantities and require special shipping considerations [30].

Experimental Evidence: A 2019 evaluation of six preservation solutions found that samples preserved with Norgen and OMNIgene.GUT showed the least shift in community composition after 7 days at room temperature compared to -80°C standards. RNAlater was less effective at preventing bacterial activity and showed larger community shifts [30].

Oral Cavity Samples

Collection Protocol:

- Saliva: Collect in sterile tubes, preferably on ice.

- Tongue/Mucosal Swabs: Use sterile synthetic-tipped swabs with consistent pressure and duration.

- Dental Plaque: Use curettes or paper points for subgingival plaque collection.

Preservation Options:

- Immediate freezing at -80°C is optimal.

- DNA/RNA Shield buffer (Zymo Research) provides a reliable room-temperature alternative, preserving microbial diversity comparably to freezing for at least 7 days [34].

Experimental Evidence: A 2025 study demonstrated that saliva, tongue swabs, and dental pocket samples stored in DNA/RNA Shield buffer at room temperature for 7 days yielded highly comparable microbial composition to frozen controls, with even increased DNA yield in some sample types [34].

Respiratory Samples

Collection Protocol:

- Use flocked swabs for oropharyngeal sampling.

- Collect sputum in sterile containers.

Preservation and Stability:

- Store swabs dry at 4°C or lower for transport.

- Long-term storage at -80°C is recommended.

- Studies show microbial community profiles in oropharyngeal swabs remain stable at 4°C, -20°C, and -80°C for at least 4 weeks, but degrade at 37°C [35].

Low-Biomass and Air Samples

Special Considerations: Low-biomass samples (air, certain tissues, drinking water) present unique challenges due to their heightened susceptibility to contamination [31].

Air Sampling Protocol:

- Impactor Samplers: Use solid or adhesive media for particle collection.

- Liquid Impingers: Collect microorganisms into specific chemical liquids like phosphate-buffered distilled water (pH 7.2).

- Filtration Samplers: Use gelatin or cellulose membrane filters.

- Wet Cyclone Samplers: Operate at high flow rates (450 L/min) with PBS buffer containing antibiotics (tetracycline, gentamycin, chloramphenicol) [36].

Preservation:

- Process air samples within 4 hours of collection when possible.

- Add glycerol to samples for -80°C storage if analysis is delayed [36].

Comparative Analysis of Preservation Methods

Table 1: Performance of stool preservation solutions after 7 days at room temperature

| Preservation Solution | Community Composition Shift | Inhibition of Bacterial Activity | DNA Yield | Suitability for Shipping |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norgen Biotek | Minimal shift | Efficient inhibition | High | Yes |

| OMNIgene.GUT | Minimal shift | Efficient inhibition | High | Yes |

| RNAlater | Relatively larger shift | Less effective | Moderate | With caution |

| 95% Ethanol | Moderate shift | Variable | Sometimes low | Regulatory restrictions |

| DNA/RNA Shield | Moderate shift | Effective | High | Yes |

Table 2: DNA extraction method performance for human gut microbiome studies

| Extraction Method | DNA Yield | Gram-positive Bacteria Recovery | Alpha-Diversity | DNA Fragment Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-DQ (SPD + DNeasy PowerLyzer) | High | High | High | ~18,000 bp |

| S-Z (SPD + ZymoBIOMICS) | High | Moderate | Moderate | ~18,000 bp |

| DQ (DNeasy PowerLyzer) | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | ~18,000 bp |

| MN (NucleoSpin Soil) | Low | Low | Low | ~12,000 bp |

Table 3: Temperature stability of microbial communities across sample types

| Sample Type | -80°C (Gold Standard) | -20°C | 4°C | Room Temperature | 37°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Stool | Stable long-term | Stable up to 2 weeks | Stable up to 2 weeks | Use preservatives (<7 days) | Not recommended |

| Oropharyngeal Swabs | Stable >4 weeks | Stable >4 weeks | Stable >4 weeks | Limited stability | Profiles alter >4 weeks |

| Mock Communities | Stable long-term | Stable >4 weeks | Moderate stability | Variable with preservatives | Significant changes |

DNA Extraction Methodologies

Optimal Protocol for Stool Samples (S-DQ Method):

- Stool Preprocessing: Use a stool preprocessing device (SPD) to homogenize 100-250 mg of fecal material in buffer [33].

- Bead-Beating Lysis: Transfer to PowerBead tubes and lyse using a bead-beater with 0.1mm glass beads for 10 minutes [33] [37].

- DNA Purification: Follow manufacturer's protocol for DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit, including inhibitor removal steps [33].

- DNA Elution: Elute in 100 μL of Solution C6 [33].

- Quality Control: Verify DNA concentration (>5 ng/μL), fragment size (~18,000 bp), and purity (A260/280 ratio ~1.8) [33].

Experimental Evidence: A 2023 comparison of four DNA extraction methods found that SPD combined with DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil protocol (S-DQ) showed superior performance in DNA yield, alpha-diversity preservation, and recovery of Gram-positive bacteria compared to other methods [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential research reagents and kits for sample collection and preservation

| Product Name | Manufacturer | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| OMNIgene.GUT | DNA Genotek | Stool preservation | Room temperature stability, inhibits bacterial growth |

| DNA/RNA Shield | Zymo Research | Multi-sample preservation | Room temperature nucleic acid stabilization |

| RNAlater | Qiagen | Tissue and cell preservation | RNA stabilization, less effective for microbiota |

| DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit | QIAGEN | DNA extraction from tough samples | Bead-beating for Gram-positive bacteria |

| NucleoSpin Soil Kit | Macherey-Nagel | DNA from soil and stool | Effective for diverse environmental samples |

| ZymoBIOMICS DNA Mini Kit | Zymo Research | DNA from various samples | Includes inhibitor removal technology |

| QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit | QIAGEN | Rapid stool DNA extraction | Quick protocol for clinical samples |

| Iloperidone | Iloperidone for Research|High-Quality Chemical Reagent | Iloperidone for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Etravirine | Etravirine|HIV Research Compound|RUO | Etravirine is a second-generation NNRTI for HIV research. This product is For Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic applications. | Bench Chemicals |

Workflow Visualization

Proper sample collection and preservation are critical foundational steps in 16S rRNA gene sequencing workflows. The optimal approach varies significantly by sample type, with stool samples benefiting from specialized preservatives like Norgen or OMNIgene.GUT, oral samples performing well with DNA/RNA Shield buffer, and respiratory samples maintaining stability at refrigerated or frozen temperatures. For all sample types, particularly low-biomass specimens, incorporating appropriate controls and standardized DNA extraction methods with bead-beating lysis significantly enhances data reliability and comparability across studies. By implementing these evidence-based practices, researchers can minimize technical artifacts and maximize detection of true biological signals in microbial ecology research.

In microbial ecology research, particularly studies utilizing 16S rRNA gene sequencing, the DNA extraction step is a critical foundation that directly determines the accuracy and reliability of downstream results. The core challenge lies in simultaneously maximizing DNA yield while minimizing the introduction of protocol-dependent biases that distort the true representation of microbial community composition. Extraction efficiency varies significantly across different bacterial taxa due to differences in cell wall structure, making some species more resistant to lysis than others [38]. This bias is particularly problematic in low-biomass samples where contaminant DNA and stochastic effects become magnified [39]. The selection of an appropriate DNA extraction method must therefore be guided by sample type, target microorganisms, and intended downstream applications to ensure data quality and cross-study comparability.

Understanding Extraction Methodologies

Core DNA Extraction Technologies

Multiple DNA extraction approaches have been developed, each with distinct mechanisms, advantages, and limitations affecting their performance in yield and bias reduction.

Table 1: Comparison of Major DNA Extraction Methodologies

| Method | Mechanism | Best For | Yield & Quality | Bias Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precipitation Chemistry ("Salting Out") | Sequential cell lysis, protein precipitation, alcohol DNA recovery [40] | Whole blood; high-quality DNA needs [40] | High yield, minimal contamination [40] | Low bias; consistently recovers diverse taxa [40] |

| Magnetic Bead-Based | Nucleic acid binding to paramagnetic beads in PEG/salt buffer [41] | High-throughput processing; museum specimens [41] | High-quality; suitable for degraded samples [41] | Bead carryover potential; requires optimization [40] [41] |

| Column-Based (Silica Membrane) | Selective DNA binding to silica in chaotropic salts [42] [43] | Routine processing; food pathogen detection [43] | Pure DNA; effective inhibitor removal [43] | Potential bias against difficult-to-lyse species [38] |

| Phenol-Chloroform | Organic separation of DNA from proteins and lipids [40] | Historical applications; specific challenging samples | Good yield but safety concerns [40] | High bias; carrier effects, toxic residue issues [40] |

Method Selection Guidelines

The optimal DNA extraction method depends heavily on sample characteristics. For whole blood samples, precipitation chemistry methods generally provide the highest yields with minimal contamination [40]. For low-biomass samples such as nasal lining fluid or skin swabs, precipitation-based methods or specialized column-based kits with mechanical lysis have demonstrated superior performance in recovering sufficient DNA for analysis [42] [38]. In food microbiology applications like detecting Listeria monocytogenes in dairy products, column-based methods such as the Exgene Cell SV mini kit have shown excellent detection limits of 100 CFU/mL [43]. For large-scale museum specimen processing, magnetic bead-based approaches offer an optimal balance of cost-effectiveness (6-11 cents per sample) and quality for high-throughput projects [41].

Critical Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Precipitation-Based DNA Extraction from Whole Blood

Principle: This method utilizes sequential cell lysis and protein precipitation to recover high-molecular-weight genomic DNA with minimal contamination [40].

Reagents:

- EDTA-treated whole blood (EDTA is superior to heparin as an anticoagulant for DNA preservation) [40]

- Red blood cell lysis buffer

- White blood cell lysis buffer

- Proteinase K solution

- RNase A solution

- Protein precipitation solution

- Isopropanol

- 70% ethanol

- DNA hydration buffer

Procedure:

- Sample Preservation: Collect blood in EDTA tubes and refrigerate at 4°C within 2 hours if processing within 3 days, or freeze at -80°C for longer storage [40].

- Red Blood Cell Lysis: Mix 300 µL of whole blood with 900 µL of red blood cell lysis buffer by gentle inversion. Incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature. Centrifuge at 2000 × g for 10 minutes and discard supernatant completely.

- White Blood Cell Lysis: Resuspend pellet in 300 µL of white blood cell lysis buffer with gentle pipetting. Add 1.5 µL of RNase A solution, mix by inversion, and incubate for 2-5 minutes at room temperature.

- Protein Digestion: Add 100 µL of Proteinase K solution, mix thoroughly, and incubate at 56°C for 1 hour until complete lysis occurs.

- Protein Precipitation: Cool sample to room temperature. Add 300 µL of protein precipitation solution and vortex vigorously at high speed for 20 seconds. Centrifuge at 2000 × g for 10 minutes.

- DNA Precipitation: Transfer supernatant to a clean tube containing 600 µL of room-temperature isopropanol. Mix by gentle inversion until DNA threads become visible. Centrifuge at 2000 × g for 5 minutes.

- DNA Washing: Carefully discard supernatant without disturbing pellet. Add 600 µL of 70% ethanol and invert tube several times. Centrifuge at 2000 × g for 5 minutes.

- DNA Hydration: Carefully discard ethanol and air-dry pellet for 10-15 minutes. Resuspend DNA in 50-100 µL of DNA hydration buffer by incubating at 55°C for 1-2 hours with occasional gentle mixing.

Troubleshooting: If DNA yield is low, ensure minimal delay between blood collection and refrigeration. Avoid hemolysis by gentle sample handling. If DNA is difficult to resuspend, increase hydration buffer volume and extend incubation time at 55°C [40].

Protocol 2: SPRI Bead-Based DNA Extraction for Low-Biomass Specimens

Principle: This cost-effective method uses single-phase reverse immobilization (SPRI) with magnetic beads to bind nucleic acids, particularly suitable for high-throughput processing of challenging samples [41].

Reagents:

- SPRI bead solution (20% PEG-8000, 2.5 M NaCl)

- Paramagnetic beads

- Lysis buffer (40 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 1.4 M NaCl, 2% Sarkosyl, pH 8.0)

- Proteinase K (20 mg/mL)

- 80% ethanol

- TE buffer

Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Transfer up to 100 µL of sample to a 1.5 mL tube. Add 400 µL of lysis buffer and 25 µL of Proteinase K. Mix thoroughly and incubate at 56°C for 2 hours with occasional mixing.

- Bead Binding: Add 150 µL of well-mixed SPRI bead solution to the lysate. Mix thoroughly by pipetting and incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes.

- Magnetic Separation: Place tube on a magnetic stand for 5 minutes until supernatant clears. Carefully remove and discard supernatant.

- Bead Washing: With tube on magnetic stand, add 500 µL of freshly prepared 80% ethanol without disturbing beads. Incubate for 30 seconds, then remove ethanol. Repeat wash step once.

- DNA Elution: Air-dry beads for 10-15 minutes until no ethanol remains. Remove from magnetic stand and resuspend beads in 50 µL of TE buffer. Incubate at 55°C for 5 minutes with occasional mixing.

- Final Separation: Return tube to magnetic stand for 5 minutes. Transfer supernatant containing DNA to a clean tube.

Optimization Notes: For specimens with tough cell walls, incorporate a mechanical lysis step using zirconia beads before Proteinase K digestion. PEG concentration can be adjusted to optimize binding of smaller DNA fragments—higher PEG concentrations increase retention of shorter fragments [41].

Quantifying and Managing Extraction Bias

DNA extraction introduces multiple technical biases that significantly impact downstream microbial community analyses. Differential lysis efficiency across bacterial taxa represents a major source of bias, with Gram-positive bacteria typically requiring more rigorous lysis conditions than Gram-negative species due to their thicker peptidoglycan layers [38]. Contaminant DNA from reagents and kits becomes increasingly problematic in low-biomass samples, with studies showing contaminant reads ranging from 0.12% in 100 µL samples to over 54% in 1 µL seawater samples [44]. Chimera formation during PCR amplification increases with higher input DNA concentrations and can inflate diversity estimates if not properly addressed [38].

Table 2: DNA Extraction Performance Across Sample Types

| Sample Type | Optimal Method | Yield Range | Critical Parameters | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood | Precipitation chemistry | 50-500 ng/µL | Anticoagulant choice (EDTA preferred), processing time <2 hours to refrigeration [40] | [40] |

| Nasal Lining Fluid | Precipitation-based with mechanical lysis | Varies (low biomass) | Mechanical lysis essential for Gram-positive bacteria [42] | [42] |

| Dairy Products | Column-based (Exgene Cell SV) | LOD: 100 CFU/mL | Efficient inhibitor removal critical for food matrices [43] | [43] |

| Museum Specimens | SPRI bead-based | Variable (degraded) | Cost: 6-11 cents/sample; suitable for high-throughput [41] | [41] |

| Seawater (1 µL) | Chemical lysis + bead purification | 0.1-1 ng | Chemical lysis outperforms physical lysis for smallest volumes [44] | [44] |

Bias Correction Strategies

Computational correction of extraction bias using mock communities and bacterial morphological properties represents a promising approach. Recent research demonstrates that extraction bias per species is predictable by bacterial cell morphology, enabling morphology-based computational correction that significantly improves resulting microbial compositions [38]. Mock community controls containing known quantities of defined bacterial species allow researchers to quantify protocol-specific biases and adjust accordingly. Studies using ZymoBIOMICS mock communities have revealed that different extraction protocols yield significantly different microbial profiles from the same starting material, with the bias being systematic and predictable [38]. Incorporation of spike-in controls such as the strictly aerobic halophile Halomonas elongata in studies of anaerobic gut commensals enables estimation of absolute microbial abundances, moving beyond relative abundance measurements that can mask important biological changes [45].

Workflow Optimization and Visualization

DNA Extraction Method Decision Workflow

The following workflow diagram outlines a systematic approach for selecting appropriate DNA extraction methods based on sample characteristics and research objectives:

Comprehensive Bias Management Strategy

Effective management of technical biases throughout the DNA extraction process requires multiple complementary approaches:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for DNA Extraction Optimization

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Application Context | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDTA Anticoagulant | Chelates calcium to prevent coagulation; protects DNA during storage [40] | Blood collection and preservation | Superior to heparin or citrate for DNA yield and stability [40] |

| ZymoBIOMICS Mock Communities | Defined microbial communities for quantifying extraction bias [38] | Protocol validation and bias assessment | Even and staggered compositions available; essential for low-biomass studies [38] |

| SPRI Magnetic Beads | Nucleic acid binding in PEG/salt buffer; size-selective purification [41] | High-throughput extraction; degraded samples | Cost-effective when prepared in-house (6-11 cents/sample) [41] |

| Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity Mastermix | PCR amplification with high fidelity and reduced contaminants [39] | 16S rRNA gene amplification | Premixed format reduces handling; minimizes reagent contamination [39] |

| Lysing Matrix E | Mechanical cell disruption via bead beating [39] | Difficult-to-lyse specimens (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria) | Essential for unbiased lysis of diverse bacterial morphologies [39] |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum serine protease for digesting contaminating proteins | Sample lysis and protein removal | Critical for efficient lysis; aliquot to avoid freeze-thaw degradation [40] |

| DNA/RNA Shield | Stabilizes nucleic acids by inhibiting nucleases [38] | Sample storage and preservation | Particularly valuable for field collections and clinical samples [38] |

| Imperialine | Imperialine, CAS:61825-98-7, MF:C27H43NO3, MW:429.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Triolein | Triolein, CAS:122-32-7, MF:C57H104O6, MW:885.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Maximizing DNA yield while minimizing technical bias requires a comprehensive strategy addressing the entire workflow from sample collection to data analysis. Key principles include: (1) matching extraction methodology to sample characteristics and research objectives, with precipitation methods ideal for high-quality DNA needs and magnetic bead-based approaches offering cost-effective solutions for large-scale studies; (2) implementing rigorous bias control measures including mock communities, negative controls, and mechanical lysis for difficult-to-lyse taxa; and (3) applying computational corrections where possible, particularly for morphology-based extraction biases. As microbial ecology continues to advance toward more quantitative applications, standardization and transparency in DNA extraction methodologies will be essential for generating comparable, reproducible data across studies and laboratories.